Western African Ebola epidemic

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 91 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 91 min

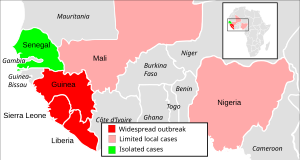

Simplified Ebola virus epidemic situation map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | December 2013 – June 2016[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casualties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

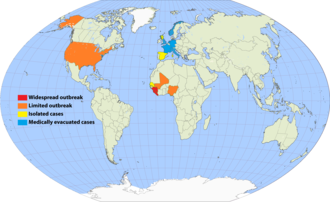

The 2013–2016 epidemic of Ebola virus disease, centered in West Africa, was the most widespread outbreak of the disease in history. It caused major loss of life and socioeconomic disruption in the region, mainly in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. The first cases were recorded in Guinea in December 2013; the disease spread to neighbouring Liberia and Sierra Leone,[12] with minor outbreaks occurring in Nigeria and Mali.[13][14] Secondary infections of medical workers occurred in the United States and Spain.[15][16] Isolated cases were recorded in Senegal,[17] the United Kingdom and Italy.[18][19] The number of cases peaked in October 2014 and then began to decline gradually, following the commitment of substantial international resources.

It caused significant mortality, with a considerable case fatality rate.[12][18][20][note 1] By the end of the epidemic, 28,616 people had been infected; of these, 11,310 had died, for a case-fatality rate of 40%.[21] As of 8 May 2016[update], the World Health Organization (WHO) and respective governments reported a total of 28,646 suspected cases and 11,323 deaths[22] (39.5%), though the WHO believes that this substantially understates the magnitude of the outbreak.[23][24] On 8 August 2014, a Public Health Emergency of International Concern was declared[25] and on 29 March 2016, the WHO terminated the Public Health Emergency of International Concern status of the outbreak.[26][27][28] Subsequent flare-ups occurred; the epidemic was finally declared over on 9 June 2016, 42 days after the last case tested negative on 28 April 2016 in Monrovia.[29]

The outbreak left about 17,000 survivors of the disease, many of whom report post-recovery symptoms termed post-Ebola syndrome, often severe enough to require medical care for months or even years. An additional cause for concern is the apparent ability of the virus to "hide" in a recovered survivor's body for an extended period and then become active months or years later, either in the same individual or in a sexual partner.[30] In December 2016, the WHO announced that a two-year trial of the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine appeared to offer protection from the variant of EBOV responsible for the Western Africa outbreak. The vaccine is considered to be effective and is the only prophylactic that offers protection; hence, 300,000 doses have been stockpiled.[31][32] rVSV-ZEBOV received regulatory approval in 2019.[33][34]

Epidemiology

[edit]Outbreak

[edit]

The 2013–2016 outbreak, caused by Ebola virus (EBOV),[35] was the first anywhere in the world to reach epidemic proportions. Extreme poverty, dysfunctional healthcare systems, distrust of government after years of armed conflict, and the delay in responding for several months, all contributed to the failure to control the epidemic. Other factors, per media reports, included local burial customs of washing the body and the unprecedented spread of Ebola to densely populated cities.[36][37][38][39][40]

It is generally believed that a one or two-year-old boy,[41][42] later identified as Emile Ouamouno, who died in December 2013 in the village of Méliandou in Guinea,[43] was the index case.[44] His mother, sister, and grandmother later became ill with similar symptoms and also died; people infected by these initial cases spread the disease to other villages.[45][46] These early cases were diagnosed as other conditions more common to the area and the disease had several months to spread before it became recognised as Ebola.[44][45]

On 25 March 2014, the WHO indicated that Guinea's Ministry of Health had reported an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in four southeastern districts and that suspected cases in the neighbouring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone were being investigated. In Guinea, a total of 86 suspected cases, including 59 deaths, had been reported as of 24 March.[47] By late May, the outbreak had spread to Conakry, Guinea's capital—a city of about two million people.[47] On 28 May, the total number of reported cases had reached 281, with 186 deaths.[47]

In Liberia, the disease was reported in four counties by mid-April 2014 and cases in Liberia's capital Monrovia were reported in mid-June.[48] The outbreak then spread to Sierra Leone and progressed rapidly. By 17 July, the total number of suspected cases in the country stood at 442, surpassing those in Guinea and Liberia.[49] By 20 July, additional cases of the disease had been reported by the media in the Bo District, while the first case in Freetown, Sierra Leone's capital, was reported in late July.[50][51]

As the epidemic progressed, a small outbreak occurred in Nigeria that resulted in 20 cases and another in Mali with seven cases. Four other countries (Senegal, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States) also reported cases imported from Western Africa, with widespread and intense transmission.[52][53][54]

On 28 January 2015, the WHO reported that for the first time since the week ending 29 June 2014, there had been fewer than 100 new confirmed cases reported in a week in the three most-affected countries. The response to the epidemic then moved to a second phase, as the focus shifted from slowing transmission to ending the epidemic.[55] On 8 April 2015, the WHO reported a total of only 30 confirmed cases,[56] and the weekly update for 29 July reported only seven new cases.[57] Cases continued to gradually dwindle and on 7 October 2015, all three of the most seriously affected countries, per media reports, recorded their first joint week without any new cases.[58] However, sporadic new cases were still being recorded, frustrating hopes that the epidemic could be declared over.[59] On 31 March 2015, one year after the first report of the outbreak, the total number of cases was over 25,000—with over 10,000 deaths.[60] As the main epidemic was coming to an end in December 2015, the UN announced that 22,000 children had lost one or both parents to Ebola.[61]

On 14 January 2016, after all the previously infected countries had been declared Ebola-free, the WHO reported that "all known chains of transmission have been stopped in Western Africa", but cautioned that further small outbreaks of the disease could occur.[62] The following day, Sierra Leone confirmed its first new case since September 2015.[28]

Countries that experienced widespread transmission

[edit]

Guinea

[edit]On 25 March 2014, the WHO reported an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in four southeastern districts of Guinea with a total of 86 suspected cases, including 59 deaths. MSF assisted the Ministry of Health by establishing Ebola treatment centres in the epicentre of the outbreak.[47] On 31 March, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sent a team to assist in the response.[47] Thinking that the spread of the virus had been contained, MSF closed its treatment centres in May, leaving only a skeleton staff to handle the Macenta region. However, in late August, according to media reports, large numbers of new cases reappeared in the region.[63]

In February 2015, Guinea recorded a rise in cases; health authorities stated that this was related to the fact that they "were only now gaining access to faraway villages", where violence had previously prevented them from entering.[64] On 14 February, violence erupted and an Ebola treatment centre near the centre of the country was destroyed. Guinean Red Cross teams said they had suffered an average of 10 attacks a month over the previous year;[65] MSF reported that acceptance of Ebola education remained low and that further violence against their workers might force them to leave.[66]

Resistance to interventions by health officials among the Guinean population remained greater than in Sierra Leone and Liberia, per media reports, raising concerns over its impact on ongoing efforts to halt the epidemic; in mid-March, there were 95 new cases, and on 28 March, and a 45-day "health emergency" was declared in five regions of the country.[66][67] On 25 May, six persons were placed in prison isolation after they were found travelling with the corpse of an individual who had died of the disease.[68] On 1 June, it was reported that violent protests in a north Guinean town at the border with Guinea-Bissau had caused the Red Cross to withdraw its workers.[69]

In late June 2015, the WHO reported that "weekly case incidence has stalled at between 20 and 27 cases since the end of May, whilst cases continue to arise from unknown sources of infection, and to be detected only after post-mortem testing of community deaths".[70] On 29 July, a sharp decline in cases was reported;[57] the number of cases eventually plateaued at one or two cases per week in early August.[71] On 28 October, an additional three cases were reported in the Forécariah Prefecture by the WHO.[72] On 6 November, a media report indicated Tana village to be the last known place with Ebola in the country,[73] and on 11 November, WHO indicated that no Ebola cases were reported in Guinea; this was the first time since the epidemic began that no cases had been reported in any country.[74] On 17 November, the last Ebola patient in Guinea had recovered,[75][76][77] and was discharged from the hospital on 28 November.[78] On 29 December 2015, the WHO declared Guinea Ebola-free.[79]

On 17 March 2016, the government of Guinea reported that two people had again tested positive for Ebola virus in Korokpara.[80] [81] On 19 March, it was also reported by the media that another individual had died due to the virus at the treatment centre in Nzerekore,[82] consequently, the country's government quarantined an area around the home where the cases took place.[83] On 22 March, the media reported that medical authorities in Guinea had quarantined 816 suspected contacts of the prior cases;[84][85] the same day, Liberia ordered its border with Guinea closed.[86] On 29 March, it was reported that about 1,000 contacts had been identified,[26] and on 30 March three more confirmed cases were reported.[87] On 1 April, it was reported by the media, that possible contacts, which numbered in the hundreds, had been given an experimental vaccine using a ring vaccination approach.[88][89]

On 5 April 2016, it was reported via the media, that there had been nine new cases of Ebola since the virus resurfaced, out of which eight were fatal;[90] on 1 June, after the stipulated waiting period, the WHO again declared Guinea Ebola-free.[91]

In September 2016, findings were published suggesting that the resurgence in Guinea was caused by an Ebola survivor who, after eight months of abstinence, had sexual relations with several partners, including the first victim in the new outbreak.[92][93] The disease was also spread to Liberia.[94]

Sierra Leone

[edit]

The first person reported infected in Sierra Leone, according to media reports, was a tribal healer who had been treating Ebola patients from across the nearby border with Guinea and who died on 26 May 2014; according to tribal tradition, her body was washed for burial, and this appears to have led to infections in women from neighbouring towns.[95] On 11 June Sierra Leone shut its borders for trade with Guinea and Liberia and closed some schools in an attempt to slow the spread of the virus;[96] on 30 July the government began to deploy troops to enforce quarantines.[97]

During the first week of November, reports told of a worsening situation due to intense transmission in Freetown. According to the Disaster Emergency Committee, food shortages resulting from aggressive quarantines were making the situation worse,[98] and on 4 November media reported that thousands had violated quarantine in search of food in the town of Kenema.[99] With the number of cases continuing to increase, an MSF coordinator described the situation in Sierra Leone as "catastrophic", saying, "there are several villages and communities that have been basically wiped out ... Whole communities have disappeared but many of them are not in the statistics." In mid-November, the WHO reported that, while there was some evidence that the number of cases was no longer rising in Guinea and Liberia, steep increases persisted in Sierra Leone.[52]

On 9 December 2014 news reports described the discovery of "a grim scene"—piles of bodies, overwhelmed medical personnel and exhausted burial teams—in the remote eastern Kono District.[100] On 15 December the CDC indicated that their main concern was Sierra Leone, where the epidemic had shown no signs of abating as cases continued to rise exponentially; by the second week of December, Sierra Leone had reported nearly 400 cases—more than three times the number reported by Guinea and Liberia combined. According to the CDC, "the risk we face now [is] that Ebola will simmer along, become native and be a problem for Africa and the world, for years to come".[101] On 17 December President Koroma of Sierra Leone launched "Operation Western Area Surge" and workers went door-to-door in the capital city looking for possible cases.[102][103] The operation led to 403 new reports of cases between 14 and 17 December.[102][104]

According to the 21 January 2015 WHO Situation Report, the case incidence was rapidly decreasing in Sierra Leone.[105][106][107] However, in February and March reports indicated another rise in the number of cases.[108][109][110][111] The WHO weekly update for 29 July reported a total of only three new cases, the lowest in more than a year.[57] On 17 August the country marked its first week with no new cases,[112] and one week later the last patients were released.[113] However, a new case emerged on 1 September, when a patient from Kambia District tested positive for the disease after her death;[114] her case eventually resulted in three other infections among her contacts.[115]

On 14 September 2015 Sierra Leone's National Ebola Response Centre confirmed the death of a 16-year-old in a village in the Bombali District.[116] It is suspected that she contracted the disease from the semen of an Ebola survivor who had been discharged in March 2015.[117] On 7 November 2015 the country was declared Ebola-free.[118][119]

Sierra Leone had entered a 90-day period of enhanced surveillance that was scheduled to end on 5 February 2016, when, on 14 January, a new Ebola death was reported in the Tonkolili District.[120][121] Before this case, the WHO had advised that "we still anticipate more flare-ups and must be prepared for them. A massive effort is underway to ensure robust prevention, surveillance, and response capacity across all three countries by the end of March."[122] On 16 January aid workers reported that a woman had died of the virus and that she may have exposed several individuals; the government later announced that 100 people had been quarantined.[123] Investigations indicated that the deceased was a student from Lunsar who had gone to Kambia District on 28 December 2015 before returning symptomatic. She had also visited Bombali District to consult a herbalist and had later gone to a government hospital in Magburaka. The WHO indicated that there were 109 contacts and another three missing contacts, and that the source or route of transmission that caused the fatality was unknown.[124] A second new case—a relative and caregiver of the aforementioned victim—had become symptomatic on 20 January while under observation at a quarantine centre.[125][126] On 26 January WHO Director-General, Dr Margaret Chan officially confirmed that the outbreak was not yet over;[28] that same day, it was also reported that Ebola restrictions had halted market activity in Kambia District amid protests.[127] On 8 February the last Ebola patient was also released.[128]

On 4 February 2016 the last known case tested negative for a second consecutive time and Sierra Leone commenced another 42-day countdown towards being declared Ebola-free.[129][130] On 17 March 2016 the WHO announced that the Sierra Leone flare-up was over and that no other chains of transmission were known to be active at that time.[131] By 15 July the country had discontinued testing corpses for the virus.[132]

Liberia

[edit]

In Liberia, the disease was reported in both Lofa and Nimba counties in late March 2014.[133] On 27 July, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf announced that Liberia would close its borders, with the exception of a few crossing points such as Roberts International Airport, where screening centres would be established.[134] Schools and universities were closed,[135][136] and the worst-affected areas in the country were placed under quarantine.[137]

With only 50 physicians in the entire country—one for every 70,000 citizens—Liberia was already in a healthcare crisis.[138] In September, the CDC reported that some hospitals had been abandoned, while those still functioning lacked basic facilities and supplies.[139] In October, the Liberian ambassador in Washington was reported as saying that he feared that his country may be "close to collapse";[138] by 24 October, all 15 counties had reported cases.[5][140]

By November 2014, the rate of new infections in Liberia appeared to be declining and the state of emergency was lifted. The drop in cases was believed to be related to an integrated strategy combining isolation and treatment with community behaviour change, including safe burial practices, case finding and contact tracing.[141][142] Roselyn Nugba-Ballah, leader of the Safe & Dignified Burial Practices Team during the crisis, was awarded the Florence Nightingale Medal in 2017 for her work during the crisis.[143]

In January 2015, the MSF field coordinator reported that Liberia was down to only five confirmed cases.[144] In March, after two weeks of not reporting any new cases, three new cases were confirmed.[145] On 8 April, a new health minister was named to end Ebola in the country and on 26 April, MSF handed the Ebola treatment facility over to the government.[146] On 30 April, the US shut down a special Ebola treatment unit in Liberia.[147] The last known case of Ebola died on 27 March,[148] and the country was officially declared Ebola-free on 9 May 2015. The WHO congratulated Liberia saying, "reaching this milestone is a testament to the strong leadership and coordination of Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and the Liberian Government, the determination and vigilance of Liberian communities, the extensive support of global partners, and the tireless and heroic work of local and international health teams."[149]

After three months with no new reports of cases, on 29 June Liberia reported that the body of a 17-year-old boy, who had been treated for malaria, tested positive for Ebola. The WHO said the boy had been in close contact with at least 200 people,[150] who they were following up, and that "the case reportedly had no recent history of travel, contact with visitors from affected areas, or funeral attendance." A second case was confirmed on 1 July.[151][152] After a third new case was confirmed on 2 July, and it was discovered that all three new cases had shared a meal of dog meat, researchers looked at the possibility that the meat may have been involved in the transfer of the virus.[153][154] Testing of the dog's remains, however, was negative for the Ebola virus.[155] By 9 July three more cases were discovered, bringing the total number of new cases to five, all from the same area.[156] On 14 July, a woman died of the disease in the county of Montserrado, bringing the total to 6.[157] On 20 July, the last patients were discharged,[158] and on 3 September 2015, Liberia was declared Ebola-free again.[159]

After two months of being Ebola-free, a new case was confirmed on 20 November 2015, when a 15-year-old boy was diagnosed with the virus[160][161] and two family members subsequently tested positive.[162][163] Health officials were concerned because the child had not recently travelled or been exposed to someone with Ebola and the WHO stated that "we believe that this is probably again, somehow, someone who has come in contact with a virus that had been persisting in an individual, who had suffered the disease months ago."[164] The infected boy died on 24 November,[165] and on 3 December two remaining cases were released after recovering.[166] On 16 December, the WHO reaffirmed that the cases in Liberia were the result of re-emergence of the virus in a previously infected person,[167] and there was speculation that the boy may have been infected by an individual who became infectious once more due to pregnancy, which may have weakened her immune system.[168] On 18 December, the WHO indicated that it still considered Ebola in Western Africa a public health emergency, though progress had been made.[169]

After having completed the 42 days, Liberia was declared free from the virus on 14 January 2016, effectively ending the outbreak that had started in neighbouring Guinea two years earlier. Liberia began a 90-day period of heightened surveillance, scheduled to conclude on 13 April 2016,[170] but on 1 April, it was reported that a new Ebola fatality had occurred,[171] and on 3 April, a second case was reported in Monrovia.[172] On 4 April, it was reported that 84 individuals were under observation due to contact with the two confirmed Ebola cases.[173] By 7 April, Liberia had confirmed three new cases since the virus resurfaced, and a total of 97 contacts, including 15 healthcare workers, were being monitored.[174] The index case of the new flareup was reported to be the wife of a patient who died from Ebola in Guinea; she had travelled to Monrovia after the funeral but died from the disease.[175]

On 29 April, WHO reported that Liberia had discharged the last patient. According to the WHO, tests indicated that the flare-up was likely due to contact with a prior Ebola survivor's infected body fluids.[94] On 9 June, the flare-up was declared over, and the country Ebola-free.[176][177]

Western African countries with limited local cases

[edit]Senegal

[edit]In March 2014, Senegal closed its southern border with Guinea,[178] but on 29 August, the health minister announced the country's first case, who was being treated in a Dakar hospital.[179] The patient was a native of Guinea who had travelled to Dakar, arriving on 20 August.[179] On 28 August 2014, authorities in Guinea issued an alert that a person who had been in close contact with an Ebola-infected patient had escaped their surveillance system. The alert prompted testing for Ebola at the Dakar laboratory, and the positive result launched an investigation, triggering urgent contact tracing.[179] On 10 September, it was reported that the initial case had recovered.[180] No further cases were reported,[181] and on 17 October 2014, the WHO officially declared that the outbreak in Senegal had ended.[5]

Nigeria

[edit]The first case in Nigeria was a Liberian-American, who flew from Liberia to Nigeria's most populated city of Lagos on 20 July 2014. On 6 August 2014, the Nigerian health minister told reporters that one of the nurses who attended to the Liberian had died from the disease. Five newly confirmed cases were being treated at an isolation ward.[182]

On 22 September 2014, the Nigerian health ministry announced, "As of today, there is no case of Ebola in Nigeria." According to the WHO, 20 cases and 8 deaths were confirmed, including the imported case, who also died. Four of the dead were health workers who had cared for the index case.[183]

The WHO's representative in Nigeria officially declared the country Ebola-free on 20 October 2014, stating it was a "spectacular success story".[184] Nigeria was the first African country to be declared Ebola-free.[185] This was largely due to the early quarantine efforts of Dr. Ameyo Stella Adadevoh.[186]

Mali

[edit]

On 23 October 2014, the first case of Ebola virus disease in Mali was confirmed in the city of Kayes—a two-year-old girl who had arrived from Guinea and died the next day.[187][188] Her father had worked for the Red Cross in Guinea and also in a private health clinic; he had died earlier in the month, likely from an Ebola infection contracted in the private clinic. It was later established that several family members had also died of Ebola. The family had returned to Mali after the father's funeral. All contacts were followed for 21 days, with no further spread of the disease reported.[189]

On 12 November 2014, Mali reported deaths from Ebola in an outbreak unconnected with the first case in Kayes. The first probable case was an imam who had fallen ill on 17 October in Guinea and was transferred to the Pasteur Clinic in Mali's capital city, Bamako, for treatment. He was treated for kidney failure but was not tested for Ebola; he died on 27 October and his body returned to Guinea for burial.[190] A nurse and a doctor who had treated the imam subsequently fell ill with Ebola and died.[191][192] The next three cases were a man who had visited the imam while he was in hospital, his wife and his son. On 22 November, the final case related to the imam was reported—a friend of the Pasteur Clinic nurse who had died from the Ebola virus.[193] On 12 December, the last case in treatment recovered and was discharged, "so there are no more people sick with Ebola in Mali", according to a Ministry of Health source.[194] On 18 January 2015 the country was declared Ebola-free.[13]

Other countries with limited local cases

[edit]United Kingdom

[edit]On 29 December 2014, Pauline Cafferkey, a British aid worker who had just returned to Glasgow from Sierra Leone, was diagnosed with Ebola.[195] She was treated and released from hospital on 24 January 2015.[9][196] On 8 October, she was readmitted for complications caused by the virus.[197] On 14 October, her condition was listed as "critical"[198] and 58 individuals were being monitored and 25 received an experimental vaccination, being close contacts.[199][200] On 21 October, it was reported that she had been diagnosed with meningitis caused by the virus persisting in her brain.[201] On 12 November, she was released from hospital after making a full recovery.[202] However, on 23 February, Cafferkey was admitted for a third time, "under routine monitoring by the Infectious Diseases Unit ... for further investigations".[203][204]

Italy

[edit]On 12 May 2015, it was reported that a nurse, who had been working in Sierra Leone, had been diagnosed with Ebola after returning home to the Italian island of Sardinia. He was treated at Spallanzani Hospital, the national reference centre for Ebola patients.[205] On 10 June, it was reported that he had recovered and was released from the hospital.[206]

Spain

[edit]On 5 August 2014, the Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God confirmed that Brother Miguel Pajares, who had been volunteering in Liberia, had become infected. He was evacuated to Spain and died on 12 August.[207] On 21 September it was announced that Brother Manuel García Viejo, another Spanish citizen who was medical director at the St John of God Hospital Sierra Leone in Lunsar, had been evacuated to Spain from Sierra Leone after being infected with the virus. His death was announced on 25 September.[208]

In October 2014, a nursing assistant, Teresa Romero, who had cared for these patients became unwell and on 6 October tested positive for Ebola,[209][210] making this the first confirmed case of Ebola transmission outside of Africa. On 19 October, it was reported that Romero had recovered, and on 2 December the WHO declared Spain Ebola-free.[211]

United States

[edit]On 30 September 2014, the CDC declared its first case of Ebola virus disease. Thomas Eric Duncan became infected in Liberia and travelled to Dallas, Texas, on 20 September. On 26 September, he fell ill and sought medical treatment, but was sent home with antibiotics. He returned to the hospital by ambulance on 28 September and was placed in isolation and tested for Ebola.[212][213] He died on 8 October.[214] Two cases stemmed from Duncan, when two nurses that had treated him tested positive for the virus;[215] they were declared Ebola-free on 24 and 22 October, respectively.[216][217]

A fourth case was identified on 23 October 2014, when Craig Spencer, an American physician who had returned to the United States after treating Ebola patients in Western Africa, tested positive for the virus.[218] Spencer recovered and was released from hospital on 11 November.[219]

Countries with medically evacuated cases

[edit]Many people who had become infected with Ebola were medically evacuated for treatment in isolation wards in Europe or the US. They were mostly health workers with one of the NGOs in Western Africa. Except for a single isolated case in Spain, no secondary infections occurred as a result of the medical evacuations. The US accepted four evacuees and three were flown to Germany.[220][221][222] France,[223][224] Italy,[225] the Netherlands,[226] Norway,[227][228] Switzerland,[229] and the United Kingdom received two patients (and five who were exposed).[230][231]

Unrelated outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

[edit]In August 2014, the WHO reported an outbreak of the Ebola virus in the Boende District, part of the northern Équateur province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where 13 people were reported to have died of Ebola-like symptoms.[232] Genetic sequencing revealed that this outbreak was caused by the Zaire Ebola species, which is native to the DRC; there have been seven previous Ebola outbreaks in the country since 1976. The virology results and epidemiological findings indicated no connection to the epidemic in Western Africa.[232][233] The WHO declared the outbreak over on 21 November 2014, after a total of 66 cases and 49 deaths.[234][235]

Virology

[edit]

Of the four disease-causing viruses in the genus Ebolavirus, Ebola virus (or the Zaire Ebola virus) is dangerous and is the virus responsible for the epidemic in Western Africa.[236][237] Since the discovery of the viruses in 1976, Ebola virus disease has been confined to areas in Middle Africa, where it is native. The epidemic was initially thought to be caused by a new species native to Guinea, rather than being imported from Middle to Western Africa.[44] However, further studies have shown that the outbreak was likely caused by an Ebola virus lineage that spread from Middle Africa via an animal host within the last decade, with the first viral transfer to humans in Guinea.[236][238] and with 341 genetic changes in the virion.[236]

In a report released in August 2014, researchers tracked the spread of Ebola in Sierra Leone from the group first infected—13 women who had attended the funeral of the traditional healer, where they contracted the disease. This provided "the first time that the real evolution of the Ebola virus [could] be observed in humans." The research showed that the outbreak in Sierra Leone was sparked by at least two distinct lineages introduced from Guinea at about the same time. It is not clear whether the traditional healer was infected with both variants or if perhaps one of the women attending the funeral was independently infected. As the Sierra Leone epidemic progressed, one virus lineage disappeared from patient samples, while a third one appeared.[239][240][241][242]

In January 2015, the media stated researchers in Guinea had reported mutations in the virus samples that they were looking at. According to them, "We've now seen several cases that don't have any symptoms at all, asymptomatic cases. These people may be the people who can spread the virus better, but we still don't know that yet. A virus can change itself to [become] less deadly, but more contagious and that's something we are afraid of."[243] A 2015 study suggested that accelerating the rate of mutation of the Ebola virus could make the virus less capable of infecting humans. In this animal study, the virus became practically non-viable, consequently increasing survival.[244]

Transmission

[edit]Animal to human transmission

[edit]

The initial infection is believed to occur after an Ebola virus is transmitted to a human by contact with an infected animal's body fluids. Evidence strongly implicates bats as the reservoir hosts.[245][246] Bats drop partially eaten fruit and pulp, and then land mammals feed on this fallen fruit. This chain of events forms a possible indirect means of transmission from the natural host to animal populations.[247] As primates in the area were not found to be infected and fruit bats do not live near the location of the initial zoonotic transmission event in Meliandou, Guinea, it is suspected that the index case occurred after a child had contact with an insectivorous bat from a colony near the village.[248]

The continent of Africa has experienced deforestation in several areas or regions; this may contribute to recent outbreaks, including this epidemic, as initial cases have been in the proximity of deforested lands where fruit-eating bats' natural habitat may be affected, though 100% of evidence does not as yet exist.[249][250]

Human-to-human transmission

[edit]Before this outbreak, it was believed that human-to-human transmission occurred only via direct contact with blood or bodily fluids from an infected person who is showing symptoms of infection, by contact with the body of a person who had died of Ebola, or by contact with objects recently contaminated with the body fluids of an actively ill infected person.[251][252] It is now known that the Ebola virus can be transmitted sexually. Studies have suggested that the virus can persist in seminal fluid, with a study released in September 2016 suggesting that the virus may survive more than 530 days after infection.[93] EBOV RNA in semen is not the same as perseverance of EBOV in semen, however the "clinical significance of low levels of virus RNA in convalescent" healthy individuals is unknown.[253][254]

In September 2014, the WHO reported: "No formal evidence exists of sexual transmission, but sexual transmission from convalescent patients cannot be ruled out. There is evidence that the live Ebola virus can be isolated in seminal fluids of convalescent men for 82 days after the onset of symptoms. Evidence is not available yet beyond 82 days."[255] In April 2015, following a report that the RNA virus had been detected in a semen sample six months after a man's recovery, the WHO issued a statement: "Ebola survivors should consider correct and consistent use of condoms for all sexual acts beyond three months until more information is available."[256][257]

The WHO based their new recommendations on a March 2015 case, in which a Liberian woman who had no contact with the disease other than having had unprotected sex with a man who had had the disease in October 2014, was diagnosed with Ebola.[258] On 14 September 2015, the body of a girl who had died in Sierra Leone tested positive for Ebola[116] and it was suspected that she may have contracted the disease from the semen of an Ebola survivor who was discharged in March 2015.[117] According to some news reports, a new study to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine indicated that the RNA virus could remain in the semen of survivors for up to six months,[259][260] and according to other researchers, the RNA virus could continue in semen for 82 days and maybe longer. Furthermore, Ebola RNA had been found up to 284 days post-onset of viral symptoms.[261]

Containment and control

[edit]

In August 2014, the WHO published a road map of the steps required to bring the epidemic under control and to prevent further transmission of the disease within Western Africa; the coordinated international response worked towards realising this plan.[262]

Surveillance and contact tracing

[edit]Contact tracing is an essential method of preventing the spread of the disease. This requires effective community surveillance so that a possible case of Ebola can be registered and accurately diagnosed as soon as possible, and subsequently finding everyone who has had close contact with the case and tracking them for 21 days. However, this requires careful record-keeping by properly trained and equipped staff.[263][264] WHO Assistant Director-General for Global Health Security, Keiji Fukuda, said on 3 September 2014, "We don't have enough health workers, doctors, nurses, drivers, and contact tracers to handle the increasing number of cases."[265] There was a massive effort to train volunteers and health workers, sponsored by United States Agency for International Development (USAID).[266] According to WHO reports, 25,926 contacts from Guinea, 35,183 from Liberia and 104,454 from Sierra Leone were listed and traced as of 23 November 2014.[53]

Ebola control is hindered by the fact that current diagnostic tests require specialised equipment and highly trained personnel. Since there are few suitable testing centres in Western Africa, this delays diagnosis. As of February 2015[update] many rapid diagnostic tests were under trial.[267] In September 2015, a new chip-based testing method that can detect Ebola accurately was reported. This new device allows for the use of portable instruments that can provide immediate diagnosis.[268][269]

Difficulties in attempting to halt transmission have also included the multiple disease outbreaks across country borders.[270] Dr Peter Piot, the scientist who co-discovered the Ebola virus, stated that the outbreak was not following its usual linear patterns as mapped out in earlier outbreaks—this time the virus was "hopping" all over the Western African epidemic region.[63] Furthermore, most past epidemics had occurred in remote regions, but this outbreak spread to large urban areas, which had increased the number of contacts an infected person might have and made transmission harder to track and break.[271] On 9 December, a study indicated that a single individual introduced the virus into Liberia, causing the most cases of the disease in that country.[272]

Community awareness

[edit]To reduce the spread, the WHO recommended raising community awareness of the risk factors for Ebola infection and the protective measures individuals can take.[273] These include avoiding contact with infected people and regular hand washing using soap and water.[274] A condition of extreme poverty exists in many of the areas that experienced a high incidence of infections. According to the director of the NGO Plan International in Guinea, "The poor living conditions and lack of water and sanitation in most districts of Conakry pose a serious risk that the epidemic escalates into a crisis. People do not think to wash their hands when they do not have enough water to drink."[275] One study showed that once people had heard of the Ebola virus disease, hand washing with soap and water improved, though socio-demographic factors influenced hygiene.[276] Several organisations enrolled local people to conduct public awareness campaigns among the communities in Western Africa.[277]

Denial in some affected countries also made containment efforts difficult.[278] Language barriers and the appearance of medical teams in protective suits sometimes increased fears of the virus.[279] In Liberia, a mob attacked an Ebola isolation centre, stealing equipment and "freeing" patients while shouting "There's no Ebola."[280] Red Cross staff were forced to suspend operations in southeast Guinea after they were threatened by a group of men armed with knives.[281] In September, in the town of Womey in Guinea, suspicious inhabitants wielding machetes murdered at least eight aid workers.[282]

An August 2014 study found that nearly two-thirds of Ebola cases in Guinea were believed to be due to burial practices including washing of the body of one who had died.[38][39][40][41][50][283] In November, WHO released a protocol for the safe and dignified burial of people who die from Ebola virus disease.[284] Speaking on 27 January 2015, Guinea's Grand Imam, the country's highest cleric, gave a very strong message saying, "There is nothing in the Koran that says you must wash, kiss or hold your dead loved ones," and he called on citizens to do more to stop the virus by practising safer burying rituals that do not compromise tradition.[285]

During the height of the epidemic, most schools in the three most affected countries were shut down and remained closed for several months. During the period of closure UNICEF and its partners established strict hygiene protocols to be used when the schools were reopened in January 2015. Their efforts included installing hand-washing stations and distributing millions of bars of soap and chlorine and plans for taking the temperature of children and staff at the school gate. Their efforts were complicated by the fact that less than 50% of the schools in these three countries had access to running water. In August 2015, UNICEF released a report that stated, "Across the three countries, there have been no reported cases of a student or teacher being infected at a school since strict hygiene protocols were introduced when classes resumed at the beginning of the year after a months-long delay caused by the virus."[286] Researchers presented evidence indicating that infected people that lived in low socioeconomic areas were more likely to transmit the virus to other socioeconomic status (SES) communities, in contrast to individuals in higher SES areas who were infected as well.[287] A study on Nigeria's success story stated that, in this case, a prompt response by the government and proactive public health measures had resulted in the quick control of the outbreak.[288]

During the height of the crisis, Wikipedia's Ebola page received 2.5 million page views per day, making Wikipedia one of the world's most highly used sources of medical information regarding the disease.[289][290]

Travel restrictions and quarantines

[edit]

There was serious concern that the disease would spread further within Western Africa or elsewhere in the world. On 8 August 2014, a cordon sanitaire, a disease-fighting practice that forcibly isolates affected regions, was established in the triangular area where Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone are separated only by porous borders and where 70 percent of the known cases had been found.[291] This was subsequently replaced by a series of checkpoints for hand-washing and measuring body temperature on major roads throughout the region, manned either by local volunteers or by the military.[292][293]

Many countries considered imposing travel restrictions to or from the region. On 2 September 2014, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan advised against this, saying that they were not justified and that they would prevent medical experts from entering the affected areas. UN officials working on the ground also criticised the travel restrictions, saying the solution was "not in travel restrictions but in ensuring that effective preventive and curative health measures are put in place".[294] MSF also spoke out against the closure of international borders, calling them "another layer of collective irresponsibility".[295] In December 2015, the CDC indicated that it would no longer make the recommendation for US citizens going to Sierra Leone to be extra careful. However, the CDC did further indicate that individuals travelling to the country should take precautions with sick people and body fluids, and avoid contact with animals.[296] There was concern that people returning from affected countries, such as health workers and reporters, may have been incubating the disease and become infectious after arriving. Guidelines for returning workers were issued by a number of agencies, including the CDC,[297] MSF,[298] Public Health England,[299] and Public Health Ontario.[300]

Protective clothing

[edit]

One of the primary reasons for the spread of the disease is the low-quality health systems in the parts of Africa where the disease occurs.[301] The risk of transmission is increased among those caring for people infected. Recommended measures when caring for those who are infected include medical isolation via the proper use of boots, gowns, gloves, masks, goggles, and sterilizing all equipment and surfaces.[302] One of the biggest dangers of infection faced by medical staff requires their learning how to properly suit up and remove personal protective equipment. Full training for wearing protective body clothing can take 10 to 14 days.[303]

The Ebola epidemic caused an increasing demand for protective clothing. A full set of protective clothing includes a suit, goggles, a mask, socks and boots, and an apron. Boots and aprons can be disinfected and reused, but everything else must be destroyed after use. Health workers change garments frequently, discarding gear that has barely been used. This not only takes a great deal of time but also exposes them to the virus because, for those wearing protective clothing, one of the most dangerous moments for contracting Ebola is while suits are being removed.[304] The protective clothing sets that MSF uses cost about $75 apiece. Staff who have returned from deployments to Western Africa say the clothing is so heavy that it can be worn for only about 40 minutes at a stretch. A physician working in Sierra Leone has said: "At that point, you have to exit for your safety ... Here it takes 20–25 minutes to take off a protective suit and must be done with two trained supervisors who watch every step militarily to ensure no mistakes are made because a slip-up can easily occur and of course can be fatal."[303][305] By October, there were reports that protective outfits were beginning to be in short supply and manufacturers began to increase their production.[306]

USAID published an open competitive bidding for proposals that address the challenge of developing "new practical and cost-effective solutions to improve infection treatment and control that can be rapidly deployed; 1) to help health care workers provide better care and 2) transform our ability to combat Ebola".[307][308][309] On 12 December 2014, USAID announced the result of the first selection in a press release.[310] On 17 December 2014, a team at Johns Hopkins University developed a prototype breakaway hazmat suit, and was awarded a grant from the USAID to develop it. The prototype has a small, battery-powered cooling pack on the worker's belt.[311]

The WHO recommends the use of two pairs of gloves, with the outer pair worn over the gown. Using two pairs may reduce the risk of sharp injuries; however, no evidence using more than the recommended will give additional protection. WHO also recommends the use of a coverall, which is generally appraised in terms of its resistance to non-enveloped DNA viruses.[312] According to guidelines released by the CDC in August 2015, updates were put in place to improve the PAPR doffing method to make the steps easier, and affirm the importance of cleaning the floor where doffing has been done. Additionally, a designated doffing assistant was recommended to help in this process.[313]

Treatment and management

[edit]

No proven Ebola virus-specific treatment presently exists;[314][315] however, measures can be taken to improve a patient's chances of survival.[316] Symptoms usually begin with a sudden influenza-like illness characterised by feeling tired, and pain in the muscles and joints. Later symptoms often include severe vomiting and diarrhoea.[317][318] In past outbreaks, it has been noted that some patients bleed internally and/or externally; however data published in October 2014 showed that this had been a rare symptom in the Western African outbreak.[319]

Without fluid replacement, such an extreme loss of fluids leads to dehydration, which in turn may lead to hypovolaemic shock—a condition in which there is not enough blood for the heart to pump through the body. If a patient is alert and is not vomiting, oral rehydration therapy may be instituted, but patients who are vomiting or are delirious must be hydrated with intravenous (IV) therapy.[314][320] However, administration of IV fluids is difficult in the African environment. Inserting an IV needle while wearing three pairs of gloves and goggles that may be fogged is difficult, and once in place, the IV site and line must be constantly monitored. Without sufficient staff to care for patients, needles may become dislodged or pulled out by a delirious patient. A patient's electrolytes must be closely monitored to determine correct fluid administration, for which many areas did not have access to the required laboratory services.[321]

Treatment centres were overflowing with patients while others waited to be admitted; dead patients were so numerous that it was difficult to arrange for safe burials. MSF took a conservative approach. While using IV treatment for as many patients as they could manage, they argued that improperly managed IV treatment was not helpful and may even kill a patient. They also said that they were concerned about further risk to already overworked staff.[321] In 2015 experts studied the mortality rates of different treatment settings, and given the wide differences in variables that affected outcomes, adequate information had not yet been gathered to make a definitive statement about what constituted optimal care in the Western African setting.[322] Paul Farmer of Partners in Health, an NGO that began to treat Ebola patients in January 2015, strongly supported IV therapy for all Ebola patients stating: "What if the fatality rate isn't the virulence of disease but the mediocrity of the medical delivery?" Farmer suggested that every treatment facility should have a team that specializes in inserting IVs, or better yet, peripherally inserted central catheter lines.[321] In 2020, viewing the information gathered from the pandemic Farmer noted that there were almost no deaths in the U.S. and European patients because they had received optimal care.[323]

Post-Ebola virus syndrome

[edit]There are at least 17,000 people who have survived infection from the Ebola virus in Western Africa; some of them have reported lingering health effects.[324] In early November, a WHO consultant reported: "Many of the survivors are discharged with the so-called Post-Ebola Syndrome. We want to ascertain whether these medical conditions are due to the disease itself, the treatment given or chlorine used during disinfection of the patients. This is a new area for research; little is known about the post-Ebola symptoms."[325][326] In August 2015, the WHO held a meeting to work out a "Comprehensive care plan for Ebola survivors" and identify research needed to optimise clinical care and social well-being. Stating that "the Ebola outbreak has decimated families, health systems, economies, and social structures", the WHO called the aftermath of the epidemic "an emergency within an emergency."[327][328] On 22 January, the WHO issued Clinical Care for Survivors of Ebola Virus Disease: Interim Guidance. The guidance covers specific issues like musculoskeletal pain, which is reported in up to 75% of survivors. The pain is symmetrical and more pronounced in the morning, with the larger joints most affected. There is also possible periarticular tenosynovitis affecting the shoulders. The WHO guidelines advise to distinguish non-inflammatory arthralgia from inflammatory arthritis. Concerning ocular problems, sensitivity to light and blurry vision have been indicated among survivors. Among the aftereffects of Ebola virus disease, uveitis and optic nerve disease could appear after an individual is discharged. Ocular problems could threaten sight in survivors, thus the need for prompt treatment. In treating such individuals, the WHO recommends urgent intervention if uveitis is suspected. Hearing loss has been reported in Ebola survivors 25% of the time.[329]

In February 2015, a Sierra Leone physician said about half of the recovered patients she saw reported declining health and that she had seen survivors go blind.[330][331] In May 2015, a senior consultant to the WHO said that the reports of eye problems were especially worrying because "there are hardly any ophthalmologists in Western Africa, and only they have the skills and equipment to diagnose conditions like uveitis that affect the inner chambers of the eye."[332]

Level of care

[edit]

As the outbreak progressed, the media reports, many hospitals, short on both staff and supplies, were overwhelmed and closed down, leading some health experts to state that the inability to treat other medical needs may have been causing "an additional death toll [that is] likely to exceed that of the outbreak itself".[333][334] There were also reports that adequate personal protection equipment was not being provided for medical personnel.[335] The Director-General of MSF said: "Countries affected to date simply do not have the capacity to manage an outbreak of this size and complexity on their own. I urge the international community to provide this support on the most urgent basis possible."[270]

Hospital workers, who worked closely with the highly contagious body fluids of the victims, were especially vulnerable to contracting the virus; in August 2014, the WHO reported that ten percent of the dead had been healthcare workers.[336] In late August, MSF called the situation "chaotic" and the medical response "inadequate." They reported that they had expanded their operations, but couldn't keep up with the rapidly increasing need for assistance, which had forced them to reduce the level of care: "It is not currently possible, for example, to administer intravenous treatments." Calling the situation "an emergency within the emergency", MSF reported that many hospitals had shut down due to a lack of staff or fears of the virus among patients and staff, which had left people with other health problems without any care at all. Speaking from a remote region, an MSF worker said that a shortage of protective equipment was making the medical management of the disease difficult and that they had limited capacity to safely bury bodies.[337] In September 2014, it was estimated that the affected countries' capacity for treating Ebola patients was insufficient by the equivalent of 2,122 beds.[338] Speaking on 12 September, WHO Director-General, Margaret Chan, said: "In the three hardest hit countries, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, the number of new cases is moving far faster than the capacity to manage them in the Ebola-specific treatment centres. Today, there is not one single bed available for the treatment of an Ebola patient in the entire country of Liberia."[339] According to a WHO report released on 19 September, Sierra Leone was meeting only 35% of its need for patient beds, while for Liberia it was just 20%.[340]

By December 2014 there were enough beds to treat and isolate all reported cases, although the uneven distribution of cases was resulting in serious shortfalls in some areas.[338] Similarly, all affected countries had sufficient and widespread capacity to bury reported deaths; however, because not all deaths were reported, it was possible that the reverse could have been the case in some areas. WHO also reported that every district had access to a laboratory to confirm cases of Ebola within 24 hours of sample collection and that all three countries had reported that more than 80% of registered contacts associated with known cases of Ebola virus disease were being traced, although contact tracing was still a challenge in areas of intense transmission and those with community resistance.[338] It has been suggested that the loss of human life was not limited to Ebola victims alone. Many hospitals had to shut down, leaving people with other medical needs without care. A spokesperson for the UK-based health foundation, the Wellcome Trust, said in October 2014 that "the additional death toll from malaria and other diseases [is] likely to exceed that of the outbreak itself".[333] Dr Paul Farmer stated: "Most of Ebola's victims may well be dying from other causes: women in childbirth, children from diarrhoea, people in road accidents or from trauma of other sorts."[334] As the epidemic drew to a close in 2015, a report from Sierra Leone showed that the fear and mistrust of hospitals generated by the epidemic had resulted in an 11% decline in facility-based births and that those receiving care before or after birth fell by about a fifth. Consequently, between May 2014 and April 2015, the deaths of women during or just after childbirth rose by almost a third and those of newborns by a quarter, compared to the previous year.[341]

Healthcare settings

[edit]

Several Ebola treatment centres were set up in the area, supported by international aid organisations and staffed by a combination of local and international staff. An important part of each centre is an arrangement for the safe burial or cremation of bodies, required to prevent further infection.[342][343] In January 2015, a new treatment and research centre was built by Rusal and Russia in the city of Kindia in Guinea. It is one of the most modern medical centres in Guinea.[344][345] Also in January, MSF admitted its first patients to a new treatment centre in Kissy, an Ebola hotspot on the outskirts of Freetown, Sierra Leone. The centre has a maternity unit for pregnant women with the virus.[346][347]

Although the WHO does not advise caring for Ebola patients at home, in some cases it became a necessity when no hospital treatment beds were available. For those being treated at home, the WHO advised informing the local public health authority and acquiring appropriate training and equipment.[348][349] UNICEF, USAID and Samaritan's Purse began to take measures to provide support for families that were forced to care for patients at home by supplying caregiver kits intended for interim home-based interventions. The kits included protective clothing, hydration items, medicines, and disinfectant, among other items.[350][351] Even where hospital beds were available, it was debated whether conventional hospitals are the best place to care for Ebola patients, as the risk of spreading the infection is high.[352] In October, the WHO and non-profit partners launched a program in Liberia to move infected people out of their homes into ad hoc centres that could provide rudimentary care.[353] Health facilities with low-quality systems for preventing infection were involved as sites of amplification during viral outbreaks.[354]

In the hardest hit areas there have historically been only one or two doctors available to treat 100,000 people and these doctors are heavily concentrated in urban areas.[271] Ebola patients' healthcare providers, as well as family and friends, are at highest risk of getting infected because they are more likely to come in direct contact with their blood or body fluids. In some places affected by the outbreak, care may have been provided in clinics with limited resources, and workers could be in these areas for several hours with many Ebola-infected patients.[355] According to the WHO, the high proportion of infected medical staff could be explained by a lack of adequate manpower to manage such a large outbreak, shortages of protective equipment or improper use of what was available, and "the compassion that causes medical staff to work in isolation wards far beyond the number of hours recommended as safe".[271] In August 2014, healthcare workers represented nearly 10 percent of cases and fatalities—significantly impairing the capacity to respond to an outbreak in an area already facing severe shortages.[356] By 1 July 2015, the WHO reported that a total of 874 health workers had been infected, of which 509 had died.[357]

Basing their choice on "the person or persons who most affected the news and our lives, for good or ill, and embodied what was important about the year", the editors of Time magazine in December 2014 named the Ebola health workers as Person of the Year. Editor Nancy Gibbs said: "The rest of the world can sleep at night because a group of men and women are willing to stand and fight. For tireless acts of courage and mercy, for buying the world time to boost its defences, for risking, for persisting, for sacrificing and saving, the Ebola fighters are Time's 2014 Person of the Year."[358] According to an October 2015 report by the CDC, Guinean healthcare workers had 42.2 times higher Ebola infection rates than non-healthcare workers, and male healthcare workers were more affected than their female counterparts. The report indicated that 27% of Ebola infections among healthcare workers in Guinea occurred among doctors. The CDC further indicated that healthcare workers in Guinea were less likely to report contact with an infected individual than non-healthcare workers.[359]

Experimental treatments

[edit]

There is no confirmed medication or treatment for Ebola virus disease.[360][361] A number of experimental treatments are undergoing clinical trials.[362][363][364] During the epidemic some patients received experimental blood transfusions from Ebola survivors, but a later study found that the treatment did not provide significant benefit.[365]

Vaccines

[edit]Several Ebola vaccine candidates had been developed in the decade before 2014 and had been shown to protect nonhuman primates against infection, but none had yet been approved for clinical use in humans.[366][367][368][369] About 15 different vaccines were in preclinical stages of development,[370] and there were two phase III studies being conducted with two different vaccines.[370]

In July 2015, researchers announced that a vaccine trial in Guinea had been completed that appeared to give protection from the virus. The vaccine, rVSV-ZEBOV,[371] had shown high efficacy in individuals, but more conclusive evidence was needed regarding its capacity to protect populations through herd immunity. The vaccine trial employed ring vaccination, in which health workers control an outbreak by vaccinating all suspected infected individuals within the surrounding area.[372][373][374][375] In December 2016, the results of the two-year Guinea trial were published announcing that rVSV-ZEBOV had been found to protect people who had been exposed to cases of Ebola.[31] In addition to showing high efficacy among those vaccinated, the trial also showed that unvaccinated people were indirectly protected from the Ebola virus through herd immunity. The vaccine has not yet had regulatory approval, but it is considered to be so effective that 300,000 doses have already been stockpiled. Not yet known is the length of time that a vaccination will be effective and whether it will prove effective for the Sudan virus.[32][376] In April 2018 rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine was used to stop an outbreak for the first time, the 2018 Équateur province Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus outbreak.[377] rVSV-ZEBOV received regulatory approval in 2019.[33][34]

Outlook

[edit]From the beginning of the outbreak, there existed considerable difficulty in getting reliable estimates—both of the number of people affected and of its geographical extent.[378] The three most affected countries—Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone—are among the poorest in the world, with extremely low levels of literacy, few hospitals or doctors, low-quality physical infrastructure, and weakly functioning government institutions.[379] One study yielded results of the spatio-temporal evolution of the viral outbreak. With the use of heat maps, it was determined that the outbreak did not uniformly unfold over the affected community areas, indicating that monitoring the outbreak at the district level was important. The study showed that accurate predictions of growth were improbable.[380]

Calculating the case fatality rate (CFR) accurately is difficult in an ongoing epidemic due to differences in testing policies, the inclusion of probable and suspected cases, and the inclusion of new cases that have not run their course. Ebola virus disease has a high CFR, which in past outbreaks varied between 25% and 90%, with an average of about 50%.[381] In August 2014, the WHO made an initial CFR estimate of 53%, though this included suspected cases.[382][383] In September and December 2014, the WHO released revised and more accurate CFR figures of 70.8% and 71% respectively, using data from patients with definitive clinical outcomes.[12][20][18] The CFR among hospitalised patients, based on the three intense-transmission countries, was between 57% and 59% in January 2015.[384] Care settings that have access to medical expertise may increase survival by providing good maintenance of hydration, circulatory volume, and blood pressure.[319] The disease affects males and females equally and the majority of those who contract Ebola disease are between 15 and 45 years of age.[12] For those over 45 years, a fatal outcome was more likely in the Western African epidemic, as was also noted in preceding outbreaks.[319] Only rarely do pregnant women survive—a midwife who worked with MSF in a Sierra Leone treatment centre stated that she knew of "no reported cases of pregnant mothers and unborn babies surviving Ebola in Sierra Leone."[385]

The basic reproduction number, R0, is a statistical measure of the average number of people infected by a single infectious individual in a population with no prior immunity. If the basic reproduction number is less than 1, the epidemic will die out; if it is greater than 1, the epidemic will continue to spread—with exponential growth in the number of cases.[386] In September 2014, the estimated values of R0 were 1.71 (95% CI, 1.44 to 2.01) for Guinea, 1.83 (95% CI, 1.72 to 1.94) for Liberia, and 2.02 (95% CI, 1.79 to 2.26) for Sierra Leone.[12][387][388]

In October 2014, the WHO noted that exponential increase of cases continued in the three countries with the most intense transmission.[389]

Projections of future cases

[edit]On 28 August 2014, the WHO released its first estimate of the possible total cases from the outbreak as part of its roadmap for stopping the transmission of the virus. It stated:

This Roadmap assumes that in many areas of intense transmission, the actual number of cases may be two- to fourfold higher than that currently reported. It acknowledges that the aggregate caseload of Ebola could exceed 20,000 over the course of this emergency. The Roadmap assumes that a rapid escalation of the complementary strategies in intense transmission, resource-constrained areas will allow the comprehensive application of more standard containment strategies within three months.

The report included an assumption that some country or countries would pay the required cost of their plan, estimated at half a billion US dollars.[262]

When the WHO released these estimates, a number of epidemiologists presented data to show that the WHO projection of a total of 20,000 cases was likely an underestimate.[390][391] On 9 September, Jonas Schmidt-Chanasit of the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Germany, controversially announced that the containment fight in Sierra Leone and Liberia had already been "lost" and that the disease would "burn itself out".[392] On 23 September 2014, the WHO revised their previous projection, stating that they expected the number of Ebola cases in Western Africa to be in excess of 20,000 by 2 November 2014.[12] They further stated, that if the disease was not adequately contained it could become native in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, "spreading as routinely as malaria or the flu",[393] and according to an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, eventually to other parts of Africa and beyond.[394]

In a report released on 23 September 2014, the CDC analysed the impact of under-reporting, which required the correction of case numbers by a factor of up to 2.5. With this correction factor, approximately 21,000 total cases were estimated for the end of September 2014 in Liberia and Sierra Leone alone. The same report predicted that total cases, including unreported cases, could reach 1.4 million in Liberia and Sierra Leone by the end of January 2015 if no improvement in intervention or community behaviour occurred.[23] However, at a congressional hearing on 19 November, the Director of the CDC said that the number of Ebola cases was no longer expected to exceed 1 million, moving away from the worst-case scenario that had been previously predicted.[395]

A study published in December 2014 found that transmission of the Ebola virus occurs principally within families, in hospitals, and at funerals. The data, gathered during three weeks of contact tracing in August, showed that the third person in any transmission chain often knew both the first and second person. The authors estimated that between 17% and 70% of cases in Western Africa were unreported—far fewer than had been estimated in prior projections. The study concluded that the epidemic would not be as difficult to control as feared if rapid, vigorous contact tracing and quarantines were employed.[396]

Projections of future cases should also reflect the possibility that deforestation might have a hand in terms of the more recent Ebola outbreaks. It has been suggested that due to the clearing of forests for commercial use, bats may be taken out of their natural habitat and therefore into closer and potential contact with civilisation.[250][249]

Economic effects

[edit]

In March 2015, the United Nations Development Group reported that due to a decrease in trade, the closing of borders, flight cancellations, and a drop in foreign investment and tourism activity fuelled by stigma, the epidemic had resulted in vast economic consequences in both the affected areas in Western Africa and other African nations with no cases of Ebola.[397] A September 2014 report in the Financial Times suggested that the economic impact of the Ebola outbreak could kill more people than the disease itself.[398]

Concerning Ebola and economic activity in the country of Liberia, a study found that 8% of automotive firms, 8% of construction firms, 15% of food businesses, and 30% of restaurants had closed due to the Ebola outbreak. Montserrado County experienced up to 20% firm closure. This indicated a decline in the Liberian national economy during the outbreak, as well as an indication that the county of Montserrado was hardest hit economically. The capital city Monrovia suffered the most construction and restaurant unemployment, while outside the capital, the food and beverage sectors suffered economically. The World Bank had projected an estimated loss of $1.6 billion in productivity for all three affected Western African countries combined for 2015. In Liberian counties that were less affected by the outbreak, the number of individuals employed fell by 24%. Montserrado saw a 47% decline in employment per firm from before the Ebola outbreak.[399]

Another study showed that the economic effect of the Ebola outbreak would be felt for years due to preexisting social vulnerability. The economic effects were being felt nationwide in Liberia, such as the termination of expansions in the mining business. Initial scenarios had placed expected economic losses at $25 billion; however subsequent World Bank estimates were much lower, at about 12% of the combined GDP of the three worst hit countries.[400] Despite the end of civil violence in 2003 and inflows from international donors, the reconstruction of Liberia had been very slow and non-productive—water delivery systems, sanitation facilities, and centralised electricity were practically non-existent, even in Monrovia. Even before the outbreak, medical facilities did not have potable water, lighting, or refrigeration. The authors indicated that lack of food and other economic effects would probably continue in the rural population long after the Ebola outbreak had ended.[400]

Other economic impacts were as follows:

- Many airlines suspended flights to the area.[401]

- Markets and shops closed due to travel restrictions, a cordon sanitaire, or fear of human contact, which led to loss of income for producers and traders.[402]

- Movement of people away from affected areas disturbed agricultural activities.[403][404] The FAO warned that the outbreak could endanger harvests and food security in Western Africa,[405] and that with all the quarantines and movement limitations placed on them, more than 1 million people could be food insecure by March 2015.[406] By 29 July, the World Bank had given 10,500 tons of maize and rice seed to the 3 hardest-hit countries to help them to rebuild their agricultural systems.[407]

- Tourism was directly impacted in the affected countries.[408] In April 2014, Nigeria reported that 75% of hotel business had been lost due to fears of the outbreak;[409] the limited Ebola outbreak had cost that country ₦8 billion.[410] Other African countries that were not directly affected by the virus also reported adverse effects on tourism,[411][412][413] including Gambia,[414][415] Ghana,[416] Kenya,[417] Zimbabwe,[418] Senegal, Zambia, and Tanzania.[419]

- Some foreign mining companies withdrew all non-essential personnel, deferred new investment, and cut back operations.[404][420][421]

In January 2015, Oxfam, a UK-based disaster relief organisation, indicated that a "Marshall Plan" (a reference to the massive plan to rebuild Europe after World War II) was needed so that countries could begin to financially assist those that had been worst hit by the virus.[422] The call was repeated in April 2015 when the most-affected Western African countries asked for an $8 billion "Marshall Plan" to rebuild their economies. Speaking at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Liberian president Ellen Johnson Sirleaf said the amount was needed because "[o]ur health systems collapsed, investors left our countries, revenues declined and spending increased."[423] The IMF has been criticised for its lack of assistance in the efforts to combat the epidemic. In December 2014, a Cambridge University study linked IMF policies with the financial difficulties that prevented a strong Ebola response in the three most heavily affected countries,[424] and they were urged by both the UN and NGOs who had worked in the affected countries to grant debt relief rather than low-interest loans. According to one advocacy group, "yet the IMF, which has made a $9 billion surplus from its lending over the last three years, is considering offering loans, not debt relief and grants, in response".[425][426] On 30 January 2015, the IMF reported it was close to reaching a deal on debt forgiveness.[427] On 22 December, it was reported that the IMF had given Liberia an additional $10 million due to the economic impact of the Ebola virus outbreak.[428]

In October 2014, a World Bank report estimated overall economic impacts of between $3.8 billion and $32.6 billion, depending on the extent of the outbreak and speed of containment. It expected the most severe losses in the three affected countries, with a wider impact across the broader Western African region.[429][430] On 13 April 2015, the World Bank said that they would soon announce a major new effort to rebuild the economies of the three hardest-hit countries.[431] On 23 July, a World Bank poll warned that "we are not ready for another Ebola outbreak".[432] On 15 December, the World Bank indicated that by 1 December 2015, it had marshalled $1.62 billion in financing for the Ebola outbreak response.[433]

On 6 July 2015, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon announced that he would host an Ebola recovery conference to raise funds for reconstruction, stating that the three countries hardest hit by Ebola needed about $700 million to rebuild their health services over a two-year period.[434] On 10 July, it was announced that the countries most affected by the Ebola epidemic would receive $3.4 billion to rebuild their economies.[435][436] On 29 September, the leaders of both Sierra Leone and Liberia indicated at the UN General Assembly the launch of a "Post-Ebola Economic Stabilization and Recovery Plan".[437] On 24 November, it was reported that due to the decrease in commodity prices and the Western African Ebola epidemic, China's investment in the continent had declined 43% in the first 6 months of 2015.[438] On 25 January, the IMF projected a GDP growth of 0.3% for Liberia, that country indicating it would cut spending by 11 per cent due to a stagnation in the mining sector, which would cause a domestic revenues drop of $57 million.[439]

Responses

[edit]In July 2014, the WHO convened an emergency meeting of health ministers from eleven countries and announced collaboration on a strategy to coordinate technical support to combat the epidemic. In August they published a road map to guide and coordinate the international response to the outbreak, aiming to stop ongoing Ebola transmission worldwide within 6–9 months, and formally designated the outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[440] This is a legal designation used only twice before (for the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic and the 2014 resurgence of poliomyelitis) that invokes legal measures on disease prevention, surveillance, control, and response, by 194 signatory countries.[441][442]

In September 2014, the United Nations Security Council declared the Ebola virus outbreak in Western Africa "a threat to international peace and security" and unanimously adopted a resolution urging UN member states to provide more resources to fight the outbreak.[443][444] In October, WHO and the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response announced a comprehensive 90-day plan to control and reverse the Ebola epidemic. The ultimate goal was to have capacity in place for the isolation of 100% of Ebola cases and the safe burial of 100% of casualties by 1 January 2015 (the 90-day target).[445] Many nations and charitable organisations cooperated to realise the plan,[446] and a WHO situation report published mid-December indicated that the international community was on track to meet the 90-day target.[447]