Yeniseian languages

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 25 min

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Yeniseian | |

|---|---|

| Yeniseic, Yeniseyan | |

| Geographic distribution | today along the Yenisei River historically large parts of Siberia and of Mongolia |

| Ethnicity | Yeniseian people |

Native speakers | 156 (2020)[1][notes 1] |

| Linguistic classification | Dené–Yeniseian?

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Yeniseian |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | yeni1252 |

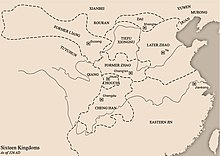

Distribution of Yeniseian languages in the 17th century (hatched) and in the end of 20th century (solid). Hydronymic data suggests that this distribution represents a northward migration of original Yeniseian populations from the Sayan Mountains and northern Mongolia. | |

The distribution of individual Yeniseian languages in 1600 | |

The Yeniseian languages (/ˌjɛnɪˈseɪən/ YEN-ih-SAY-ən; sometimes known as Yeniseic, Yeniseyan, or Yenisei-Ostyak;[notes 2] occasionally spelled with -ss-) are a family of languages that are spoken by the Yeniseian people in the Yenisei River region of central Siberia. As part of the proposed Dené–Yeniseian language family, the Yeniseian languages have been argued to be part of "the first demonstration of a genealogical link between Old World and New World language families that meets the standards of traditional comparative-historical linguistics".[2] The only surviving language of the group today is Ket.

From hydronymic and genetic data, it is suggested that the Yeniseian languages were spoken in a much greater area in ancient times, including parts of northern China and Mongolia.[3] It has been further proposed that the recorded distribution of Yeniseian languages from the 17th century onward represents a relatively recent northward migration, and that the Yeniseian urheimat lies to the south of Lake Baikal.[4]

The Yeniseians have been connected to the Xiongnu confederation, whose ruling elite may have spoken a southern Yeniseian language[according to whom?] similar to the now extinct Pumpokol language.[5] The Jie, who ruled the Later Zhao state of northern China, are likewise believed to have spoken a Pumpokolic language based on linguistic and ethnogeographic data.[6]

For those who argue[when?] the Xiongnu spoke a Yeniseian language, the Yeniseian languages are thought to have contributed many ubiquitous loanwords to Turkic and Mongolic vocabulary, such as Khan, Tarqan, and the word for 'god', Tengri.[5] This conclusion has primarily been drawn from the analysis of preserved Xiongnu texts in the form of Chinese characters.[7]

Classification

[edit]The classification of the Yeniseian languages has changed from time to time. A traditional classification is presented below:[8][9]

- Proto-Yeniseian (before 500 BC; split around 1 AD)[8]

- Northern Yeniseian (split around 700 AD)

- Southern Yeniseian †

Georg 2007[11] and Hölzl 2018[12] use a slightly different classification, placing Pumpokol in both branches:

A more recent classification, introduced in Fortescue and Vajda 2022[13] and used in Vajda 2024,[14] is presented below:

- Proto-Yeniseian

- Ketic

- Arinic

- Arin † (extinct by 1800)

- Pumpokolic

- Kottic

It has been suggested that the Xiongnu and Hunnic languages were Southern Yeniseian. Only two languages of this family survived into the 20th century: Ket (also known as Imbat Ket), with around 200 speakers, and Yugh (also known as Sym Ket), now extinct. The other known members of this family—Arin, Assan, Pumpokol, and Kott—have been extinct for over 150 years. Other groups—the Baikot, Yarin (Buklin), Yastin, Ashkyshtym (Bachat Teleuts), and Koibalkyshtym—are identifiable as Yeniseic speaking from tsarist fur-tax records compiled during the 17th century, but nothing remains of their languages except a few proper names.[15]

Distribution

[edit]Ket, the only extant Yeniseian language, is the northernmost known. Historical sources record a contemporaneous northern expansion of the Ket along the Yenisei during the Russian conquest of Siberia.[16] Today, it is mainly spoken in Turukhansky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai in far northern Siberia, in villages such as Kellog and Sulomay. Yugh, which only recently faced extinction, was spoken from Yeniseysk to Vorogovo, Yartsevo, and the upper Ket River.

The early modern distributions of Arin, Pumpokol, Kott, and Assan can be reconstructed. The Arin were north of Krasnoyarsk, whereas the more distantly related Pumpokol was spoken to the north and west of it, along the upper Ket. Kott and Assan, another pair of closely related languages, occupied the area south of Krasnoyarsk, and east to the Kan River.[17] From toponyms it can be seen that Yeniseian populations probably lived in Buryatia, Zabaykalsky, and northern Mongolia. As an example, the toponym ši can be found in Zabaykalsky Krai, which is probably related to the Proto-Yeniseian word *sēs 'river' and likely derives from an undocumented Yeniseian language. Some toponyms that appear Yeniseian extend as far as Heilongjiang.[4]

Václav Blažek argues, based on hydronymic data, that Yeniseians were once spread out even farther into the west.[of what?] He compares, for example, the word šet, found in more westerly river names, to Proto-Yeniseian *sēs 'river'.[18]

Origins and history

[edit]

According to a 2016 study, Yeniseian people and their language originated likely somewhere near the Altai Mountains or near Lake Baikal. According to this study, the Yeniseians are linked to Paleo-Eskimo groups.[19] The Yeniseians have also been hypothesised to be representative of a back-migration from Beringia to central Siberia, and the Dené–Yeniseians a result of a radiation of populations out of the Bering land bridge.[20] The spread of ancient Yeniseian languages may be associated with an ancestry component from the Baikal area (Cisbaikal_LNBA), maximized among hunter-gatherers of the local Glazkovo culture. Affinity for this ancestry has been observed among Na-Dene speakers. Cisbaikal_LNBA ancestry is inferred to be rich in Ancient Paleo-Siberian ancestry, and also display affinity to Inner Northeast Asian (Yumin-like) groups.[21]

In Siberia, Edward Vajda observed that Yeniseian hydronyms in the circumpolar region (the recent area of distribution of Yeniseian languages) clearly overlay earlier systems, with the layering of morphemes onto Ugric, Samoyedic, Turkic, and Tungusic place names. It is therefore proposed that the homeland, or dispersal point, of the Yeniseian languages lies in the boreal region between Lake Baikal, northern Mongolia, and the Upper Yenisei basin, referred to by Vajda as a territory "abandoned" by the original Yeniseian speakers.[4] On the other hand, Václav Blažek (2019) argues that based on hydronomic evidence, Yeneisian languages were originally spoken on the northern slopes of the Tianshan and Pamir Mountains before dispersing downstream via the Irtysh River.[18]

The modern populations of Yeniseians in central and northern Siberia are thus not indigenous and represent a more recent migration northward. This was noted by Russian explorers during the conquest of Siberia: the Ket are recorded to have been expanding northwards along the Yenisei, from the river Yeloguy to the Kureyka, from the 17th century onward.[16] Based on these records, the modern Ket-speaking area appears to represent the very northernmost reaches of Yeniseian migration.

The origin of this northward migration from the Mongolian steppe has been connected to the fall of the Xiongnu confederation. It appears from Chinese sources that a Yeniseian group might have been a major part of the heterogeneous Xiongnu tribal confederation,[22] who have traditionally been considered the ancestors of the Huns and other Northern Asian groups. However, these suggestions are difficult to substantiate due to the paucity of data.[23][24]

Alexander Vovin argues that at least parts of the Xiongnu, possibly its core or ruling class, spoke a Yeniseian language.[5] Positing a higher degree of similarity of Xiongnu to Yeniseian as compared to Turkic, he also praised Stefan Georg's demonstration of how the word Tengri (the Turkic and Mongolic word for 'sky' and later 'god') originated from Proto-Yeniseian tɨŋVr.[5]

It has been further suggested that the Yeniseian-speaking Xiongnu elite underwent a language shift to Oghur Turkic while migrating westward, eventually becoming the Huns. However, it has also been suggested that the core of the Hunnic language was a Yeniseian language.[25]

Vajda et al. 2013 proposed that the ruling elite of the Huns spoke a Yeniseian language and influenced other languages in the region.[3]

One sentence of the language of the Jie, a Xiongnu tribe who founded the Later Zhao state, appears consistent with being a Yeniseian language.[5] Later studies suggest that Jie is closer to Pumpokol than to other Yeniseian languages such as Ket.[6] This has been substantiated with geographical data by Vajda, who states that Yeniseian hydronyms found in northern Mongolia are exclusively Pumpokolic, in the process demonstrating both a linguistic and geographic proximity between Yeniseian and Jie.

The decline of the southern Yeniseian languages during and after the Russian conquest of Siberia has been attributed to language shifts of the Arin and Pumpokol to Khakas or Chulym Tatar, and the Kott and Assan to Khakas.[17]

Family features

[edit]

The Yeniseian languages share many contact-induced similarities with the South Siberian Turkic languages, Samoyedic languages, and Evenki. These include long-distance nasal harmony, the development of former affricates to stops, and the use of postpositions or grammatical enclitics as clausal subordinators.[26] Yeniseic nominal enclitics closely approximate the case systems of geographically contiguous families. Despite these similarities, Yeniseian appears to stand out among the languages of Siberia in several typological respects, such as the presence of tone, the prefixing verb inflection, and highly complex morphophonology.[27]

The Yeniseian languages have been described as having up to four tones or no tones at all. The 'tones' are concomitant with glottalization, vowel length, and breathy voice,[citation needed] not unlike the situation reconstructed for Old Chinese before the development of true tones in Chinese. The Yeniseian languages have highly elaborate verbal morphology.

Pronouns

[edit]| Northern branch | Pumpokolic branch | Arinic branch | Kottic branch | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ket | Yugh | Pumpokol | Arin | Kott dialects | Assan | |

| 1st sg. | āˑ(t) | āt | ad | ai | ai/aj~ja | aj |

| 2nd sg. | ūˑ | ū | u | au | au | au |

| 3rd sg. | būˑ | bū | ádu ~ bu (masc.) *ida (fem.) |

au | uju ~ hatu/xatu (masc.) uja ~ hata/xata (fem.) |

bari |

| 1st pl. | ɤ̄ˑt ~ ɤ́tn | ɤ́tn | adɨŋ | aiŋ | ajoŋ | ajuŋ |

| 2nd pl. | ɤ́kŋ | kɤ́kŋ | ajaŋ | aŋ | auoŋ ~ aoŋ | avun |

| 3rd pl. | būˑŋ | béìŋ | bueg | itaŋ | uniaŋ ~ xatien | hatin |

Numbers

[edit]The following table exemplifies the basic Yeniseian numerals as well as the various attempts at reconstructing the proto-forms:[8][15][28][9]

| Gloss | Northern branch | Pumpokolic branch | Arinic branch | Kottic branch | Reconstructions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ket dialects | Yugh | Pumpokol | Arin | Assan | Kott | ||

| SK | Starostin | ||||||

| 1 | qūˑs/𐞥χɔˀk | χūs/χɔˀk | xúta | qusej | hutʃa/hau- | huːtʃa | *xu-sa |

| 2 | ɯ̄ˑn | ɯ̄n | hínɛaŋ ~ hínɛa | kina | ina | iːna | *xɨna |

| 3 | dɔˀŋ | dɔˀŋ | dóŋa | tʲoŋa ~ tʲuːŋa | taŋa | toːŋa | *doʔŋa |

| 4 | sīˑk | sīk | ciaŋ | tʃaɡa | ʃeɡa | tʃeɡa ~ ʃeːɡa | *si- |

| 5 | qāˑk | χāk | héjlaŋ | qala | keɡa | keɡa ~ χeːɡa | *qä- |

| 6 | aˀ ~ à | àː | aɡɡiaŋ ~ áɡiang | ɨɡa | ɡejlutʃa | χelutʃa | *ʔaẋV |

| 7 | ɔˀŋ | ɔˀŋ | ónʲaŋ | ɨnʲa | ɡejlina | χelina | *ʔoʔn- |

| 8 | ɨ́nàm bʌ́nsàŋ qōˑ | bosʲim[notes 4] | hinbasiaŋ | kinamančau | gejtaŋaŋ | xeltoŋa ~ gheltoŋa | |

| 9 | qúsàm bʌ́nsàŋ qōˑ | debit[notes 4] | xutajamos xajaŋ | qusamančau | godžibunagiaŋ | hučabunaga | |

| 10 | qōˑ | χō | xaiáŋ (xajáŋ) | qau ~ hioɡa | xaha | haːɡa ~ haɡa | *ẋɔGa |

| 20 | ɛˀk | ɛˀk | hédiaŋ | kinthjuŋ | inkukn | iːntʰukŋ | *ʔeʔk ~ xeʔk |

| 100 | kiˀ | kiˀ | útamsa | jus | jus | ujaːx | *kiʔ ~ ɡiʔ / *ʔalVs-(tamsV) |

Basic vocabulary

[edit]The following table exemplifies a few basic vocabulary items as well as the various attempts at reconstructing the proto-forms:[8][15][28][9]

| Gloss | Northern branch | Pumpokolic branch | Arinic branch | Kottic branch | Reconstructions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ket dialects | Yugh | Pumpokol | Arin | Assan | Kott | ||||||

| SK | NK | CK | Vajda | Starostin | Werner | ||||||

| Larch | sɛˀs | sɛˀs | šɛˀš | sɛˀs | tag | čit | čet | šet | *čɛˀç | *seʔs | *sɛʔt / *tɛʔt |

| River | sēˑs | sēˑs | šēˑš | sēs | tat | sat | šet | šet | *cēˑc | *ses | *set / *tet |

| Stone | tʌˀs | tʌˀs | tʌˀš | čʌˀs | kit | kes | šiš | šiš | *cʰɛˀs | *čɨʔs | *t'ɨʔs |

| Finger | tʌˀq | tʌˀq | tʌˀq | tʌˀχ | tok | intoto | ? | tʰoχ | *tʰɛˀq | *tǝʔq | *thǝʔq |

| Resin | dīˑk | dīˑk | dīˑk | dʲīk | ? | ? | ? | čik | *čīˑk | *ǯik (~-g, -ẋ) | *d'ik |

| Wolf | qɯ̄ˑt | qɯ̄ˑti | qɯ̄ˑtə | χɯ̄ˑt | xótu | qut | (boru ← Turkic) | *qʷīˑtʰi | *qɨte (˜ẋ-) | *qʌthǝ | |

| Winter | kɤ̄ˑt | kɤ̄ˑti | kɤ̄ˑte | kɤ̄ˑt | lete | lot | ? | keːtʰi | *kʷeˑtʰi | *gǝte | *kǝte |

| Light | kʌˀn | kʌˀn | kʌˀn | kʌˀn | ? | lum | ? | kin | *kʷɛˀn | *gǝʔn- | – |

| Person | kɛˀd | kɛˀd | kɛˀd | kɛˀtʲ | kit | kit | het | hit | *kɛˀt | *keʔt | – |

| Two | ɯ̄ˑn | ɯ̄ˑn | ɯ̄ˑn | ɯ̄n | hin | kin | in | in | *kʰīˑn | *xɨna | *(k)ɨn |

| Water | ūˑl | ūˑl | ūˑl | ūr | ul | kul | ul | ul | *kʰul | *qoʔl (~ẋ-, -r) | – |

| Birch | ùs | ùːse | ùːsə | ùːʰs | uta | kus | uuča | uča | *kʰuχʂa | *xūsa | *kuʔǝt'ǝ |

| Snowsled | súùl | súùl | šúùl | sɔ́ùl | tsɛl | šal | čɛgar | čogar | *tsehʷəl | *soʔol | *sogǝl (~č/t'-ʎ) |

Proposed relations to other language families

[edit]Until 2008, few linguists had accepted connections between Yeniseian and any other language family, though distant connections have been proposed with most of the ergative languages of Eurasia.

Dené–Yeniseian

[edit]In 2008, Edward Vajda of Western Washington University presented evidence for a genealogical relation between the Yeniseian languages of Siberia and the Na–Dené languages of North America.[29] At the time of publication (2010), Vajda's proposals had been favorably reviewed by several specialists of Na-Dené and Yeniseian languages—although at times with caution—including Michael Krauss, Jeff Leer, James Kari, and Heinrich Werner, as well as a number of other respected linguists, such as Bernard Comrie, Johanna Nichols, Victor Golla, Michael Fortescue, Eric Hamp, and Bill Poser (Kari and Potter 2010:12).[30] One significant exception is the critical review of the volume of collected papers by Lyle Campbell[31] and a response by Vajda[32] published in late 2011 that clearly indicate the proposal is not completely settled at the present time. Two other reviews and notices of the volume appeared in 2011 by Keren Rice and Jared Diamond.

Karasuk

[edit]The Karasuk hypothesis, linking Yeniseian to Burushaski, has been proposed by several scholars, notably by A.P. Dulson[33] and V.N. Toporov.[34] In 2001, George van Driem postulated that the Burusho people were part of the migration out of Central Asia, that resulted in the Indo-European conquest of the Indus Valley.[35]

Alexei Kassian has suggested a connection between Hattic, Hurro-Urartian and Karasuk, proposing some lexical correspondences.[36]

Sino-Tibetan

[edit]As noted by Tailleur[37] and Werner,[38] some of the earliest proposals of genetic relations of Yeniseian, by M.A. Castrén (1856), James Byrne (1892), and G.J. Ramstedt (1907), suggested that Yeniseian was a northern relative of the Sino–Tibetan languages. These ideas were followed much later by Kai Donner[39] and Karl Bouda.[40] A 2008 study found further evidence for a possible relation between Yeniseian and Sino–Tibetan, citing several possible cognates.[41] Gao Jingyi (2014) identified twelve Sinitic and Yeniseian shared etymologies that belonged to the basic vocabulary, and argued that these Sino-Yeniseian etymologies could not be loans from either language into the other.[42]

The Sino-Caucasian hypothesis of Sergei Starostin posits that the Yeniseian languages form a clade with Sino-Tibetan, which he called Sino-Yeniseian. The Sino-Caucasian hypothesis has been expanded by others to "Dené–Caucasian" to include the Na-Dené languages of North America, Burushaski, Basque and, occasionally, Etruscan. A narrower binary Dené–Yeniseian family has recently been well received. The validity of the rest of the family, however, is viewed as doubtful or rejected by nearly all historical linguists.[43][44][45] An updated tree by Georgiy Starostin now groups Na-Dene with Sino-Tibetan and Yeniseian with Burushaski (Karasuk hypothesis).[46] George van Driem does not believe that Sino-Tibetan (which he calls "Trans-Himalayan") and Yeniseian are related language families. However, he argues that Yeniseian speakers once populated the North China Plain and that Proto-Sinitic speakers assimilated them when they migrated to the region. As a result, Sinitic acquired creoloid characteristics when it came to be used as a lingua franca among ethnolinguistically diverse populations.[47]

A link between the Na–Dené languages and Sino-Tibetan languages, known as Sino–Dené had also been proposed by Edward Sapir. Around 1920 Sapir became convinced that Na-Dené was more closely related to Sino-Tibetan than to other American families.[48] Edward Vadja's Dené–Yeniseian proposal renewed interest among linguists such as Geoffrey Caveney (2014) to look into support for the Sino–Dené hypothesis. Caveney considered a link between Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dené, and Yeniseian to be plausible but did not support the hypothesis that Sino-Tibetan and Na-Dené were related to the Caucasian languages (Sino–Caucasian and Dené–Caucasian).[49]

A 2023 analysis by David Bradley using the standard techniques of comparative linguistics supports a distant genetic link between the Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dené, and Yeniseian language families. Bradley argues that any similarities Sino-Tibetan shares with other language families of the East Asia area such as Hmong-Mien, Altaic (which is actually a sprachbund), Austroasiatic, Kra-Dai, Austronesian came through contact; but as there has been no recent contact between Sino-Tibetan, Na-Dené, and Yeniseian language families then any similarities these groups share must be residual.[50]

Dené–Caucasian

[edit]Bouda, in various publications in the 1930s through the 1950s, described a linguistic network that (besides Yeniseian and Sino-Tibetan) also included Caucasian, and Burushaski, some forms of which have gone by the name of Sino-Caucasian. The works of R. Bleichsteiner[51] and O.G. Tailleur,[52] the late Sergei A. Starostin[53] and Sergei L. Nikolayev[54] have sought to confirm these connections. Others who have developed the hypothesis, often expanded to Dené–Caucasian, include J.D. Bengtson,[55] V. Blažek,[56] J.H. Greenberg (with M. Ruhlen),[57] and M. Ruhlen.[58] George Starostin continues his father's work in Yeniseian, Sino-Caucasian and other fields.[59]

This theory is very controversial or viewed as doubtful or rejected by other linguists.[60][61][62]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sum of Ket and Yugh speakers in the 2021 Russian census.

- ^ "Ostyak" is a concept of areal rather than genetic linguistics. In addition to the Yeniseian languages it also includes the Uralic languages Khanty and Selkup. The term "Yenisei-Ostyak" typically refers to the Ketic branch of Yeniseian.

- ^ a b c Yastin, Yarin and Baikot are sometimes considered dialects of Kott.

- ^ a b Russian loan.

References

[edit]- ^ 7. НАСЕЛЕНИЕ НАИБОЛЕЕ МНОГОЧИСЛЕННЫХ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОСТЕЙ ПО РОДНОМУ ЯЗЫКУ

- ^ Bernard Comrie (2008) "Why the Dene-Yeniseic Hypothesis is Exciting". Fairbanks and Anchorage, Alaska: Dene-Yeniseic Symposium.

- ^ a b Vajda, Edward J. (2013). Yeniseian Peoples and Languages: A History of Yeniseian Studies with an Annotated Bibliography and a Source Guide. Oxford/New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b c Vajda, Edward. "Yeniseian and Dene Hydronyms" (PDF). Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication. 17: 183–201.

- ^ a b c d e f Vovin, Alexander (2000). "Did the Xiong Nu Speak a Yeniseian Language?". Central Asiatic Journal. 44 (1).

- ^ a b Vovin, Alexander; Vajda, Edward J.; de la Vaissière, Etienne (2016). "Who were the *Kyet (羯) and what language did they speak?". Journal Asiatique. 304 (1): 125–144.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander (2020). "Two Newly Found Xiong-nú Inscriptions and Their Significance for the Early Linguistic History of Central Asia". International Journal of Eurasian Linguistics. 2 (2): 315–322. doi:10.1163/25898833-12340036.

- ^ a b c d Vajda 2007.

- ^ a b c Werner, Heinrich (2005). Die Jenissej-Sprachen des 18. Jahrhunderts. Veröffentlichungen der Societas Uralo-Altaica. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-05239-9.

- ^ a b c Vajda, Edward. Assessing the Sino-Caucasian Hypothesis. Comparative Historical Linguistics of the 21st Century.

- ^ Georg 2007.

- ^ Hölzl, Andreas (August 29, 2018). A typology of questions in Northeast Asia and beyond. Language Science Press. ISBN 9783961101023.

- ^ Fortescue, Michael D.; Vajda, Edward J. (2022). Mid-holocene language connections between Asia and North America. Brill's studies in the indigenous languages of the Americas. Leiden ; Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-43681-7.

- ^ a b Vajda, Edward (2024-02-19), Vajda, Edward (ed.), "8 The Yeniseian language family", The Languages and Linguistics of Northern Asia, De Gruyter, pp. 365–480, doi:10.1515/9783110556216-008, ISBN 978-3-11-055621-6, retrieved 2024-06-26

- ^ a b c Vajda, Edward J. (2004). Ket. Languages of the world Materials. München: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 978-3-89586-221-2.

- ^ a b Georg, Stefan (January 2003). "The Gradual Disappearance of a Eurasian Language Family". Language Death and Language Maintenance: Theoretical, Practical and Descriptive Approaches. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. 240: 89. doi:10.1075/cilt.240.07geo. ISBN 978-90-272-4752-0.

- ^ a b Vajda, Edward J. (2004-01-01). Languages and Prehistory of Central Siberia. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-4776-6.

- ^ a b Blažek, Václav. "Toward the question of Yeniseian homeland in perspective of toponymy" (PDF).

- ^ Flegontov, Pavel; Changmai, Piya; Zidkova, Anastassiya; Logacheva, Maria D.; Altınışık, N. Ezgi; Flegontova, Olga; Gelfand, Mikhail S.; Gerasimov, Evgeny S.; Khrameeva, Ekaterina E. (2016-02-11). "Genomic study of the Ket: a Paleo-Eskimo-related ethnic group with significant ancient North Eurasian ancestry". Scientific Reports. 6: 20768. arXiv:1508.03097. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620768F. doi:10.1038/srep20768. PMC 4750364. PMID 26865217.

- ^ Sicoli, Mark A.; Holton, Gary (2014-03-12). "Linguistic Phylogenies Support Back-Migration from Beringia to Asia". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e91722. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...991722S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091722. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3951421. PMID 24621925.

- ^ Zeng, Tian Chen; et al. (2 October 2023). "Postglacial genomes from foragers across Northern Eurasia reveal prehistoric mobility associated with the spread of the Uralic and Yeniseian languages". BioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2023.10.01.560332. S2CID 263706090.

- ^ See Vovin 2000, Vovin 2002 and Pulleyblank 2002

- ^ See Vajda 2008a

- ^ Sinor, Denis (1996). "23.4 The Xiongnu Empire". In Herrmann, J.; Zürcher, E. (eds.). History of Humanity. Multiple History. Vol. III: From the Seventh Century B.C. to the Seventh Century A.D. UNESCO. p. 452. ISBN 978-92-3-102812-0.

- ^ E. G. Pulleyblank, "The consonontal system of old Chinese" [Pt 1], Asia Major, vol. IX (1962), pp. 1–2.

- ^ See Anderson 2003

- ^ Georg, Stefan (2008). "Yeniseic languages and the Siberian linguistic area". Evidence and Counter-Evidence. Festschrift Frederik Kortlandt. Studies in Slavic and General Linguistics. Vol. 33. Amsterdam / New York: Rodopi. pp. 151–168.

- ^ a b Starostin 1982.

- ^ See Vajda 2010

- ^ Language Log » The languages of the Caucasus

- ^ Lyle Campbell, 2011, "Review of The Dene-Yeniseian Connection (Kari and Potter)," International Journal of American Linguistics 77:445–451. "In summary, the proposed Dene-Yeniseian connection cannot be embraced at present. The hypothesis is indeed stimulating, advanced by a serious scholar trying to use appropriate procedures. Unfortunately, neither the lexical evidence (with putative sound correspondences) nor the morphological evidence adduced is sufficient to support a distant genetic relationship between Na-Dene and Yeniseian." (pg. 450).

- ^ Edward Vajda, 2011, "A Response to Campbell," International Journal of American Linguistics 77:451–452. "It remains incumbent upon the proponents of the DY hypothesis to provide solutions to at least some of the unresolved problems identified in Campbell's review or in DYC itself. My opinion is that every one of them requires a convincing solution before the relationship between Yeniseian and Na-Dene can be considered settled." (pg. 452).

- ^ See Dulson 1968

- ^ See Toporov 1971

- ^ See Van Driem 2001

- ^ Kassian, A. (2009–2010) Hattic as a Sino-Caucasian language // Ugarit-Forschungen. Internationales Jahrbuch für die Altertumskunde Syrien-Palästinas. Bd 41. pp 309–447.

- ^ See Tailleur 1994

- ^ See Werner 1994

- ^ See Donner 1930

- ^ See Bouda 1963 and Bouda 1957

- ^ Sedláček, Kamil (2008). "The Yeniseian Languages of the 18th Century and Ket and Sino-Tibetan Word Comparisons". Central Asiatic Journal. 52 (2): 219–305. doi:10.13173/CAJ/2008/2/6. ISSN 0008-9192. JSTOR 41928491. S2CID 163603829.

- ^ 高晶一, Jingyi Gao (2017). "Xia and Ket Identified by Sinitic and Yeniseian Shared Etymologies // 確定夏國及凱特人的語言為屬於漢語族和葉尼塞語系共同詞源". Central Asiatic Journal. 60 (1–2): 51–58. doi:10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051. ISSN 0008-9192. JSTOR 10.13173/centasiaj.60.1-2.0051. S2CID 165893686.

- ^ Goddard, Ives (1996). "The Classification of the Native Languages of North America". In Ives Goddard, ed., "Languages". Vol. 17 of William Sturtevant, ed., Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pg. 318

- ^ Trask, R. L. (2000). The Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pg. 85

- ^ Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Peiros, Ilia; Lin, Marie (2008). Past Human Migrations in East Asia: Matching Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. Routledge. ISBN 9781134149629.

- ^ The Preliminary Genealogical Tree For Eurasia (short variant)

- ^ Driem, George van (2021). Ethnolinguistic prehistory: the peopling of the world from the perspective of language, genes and material culture. Brill's Tibetan studies library. Leiden Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-44837-7.

- ^ Ruhlen, Merritt (1998-11-10). "The origin of the Na-Dene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (23): 13994–13996. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9513994R. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13994. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 25007. PMID 9811914.

- ^ Caveney, Geoffrey (2014). "Sino-Tibetan ŋ- and Na-Dene *kw- / *gw- / *xw-: 1st Person Pronouns and Lexical Cognate Sets". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 42 (2): 461–487. JSTOR 24774894.

- ^ Bradley, David (2023-07-24). "Ancient Connections of Sinitic". Languages. 8 (3): 176. doi:10.3390/languages8030176. ISSN 2226-471X.

- ^ See Bleichsteiner 1930

- ^ See Tailleur 1958 and Tailleur 1994

- ^ See Starostin 1982, Starostin 1984, Starostin 1991, Starostin & Ruhlen 1994

- ^ See Nikola(y)ev 1991

- ^ See Bengtson 1994, Bengtson 1998, Bengtson 2008

- ^ See Blažek & Bengtson 1995

- ^ See Greenberg & Ruhlen, Greenberg & Ruhlen 1997

- ^ See Ruhlen 1997, Ruhlen 1998a, Ruhlen 1998b

- ^ See Reshetnikov & Starostin 1995a, Reshetnikov & Starostin 1995b, Dybo & Starostin

- ^ Trask, R. L. (2000). The Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pg. 85

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (1998). Dictionary of Languages. New York: Columbia University Press. pg. 434

- ^ Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia; Blench, Roger; Ross, Malcolm D.; Peiros, Ilia; Lin, Marie (2008-07-25). Past Human Migrations in East Asia: Matching Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. Routledge. ISBN 9781134149629.

Bibliography

[edit]- Anderson, G. (2003) 'Yeniseic languages in Siberian areal perspective', Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung 56.1/2: 12–39. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

- Anonymous. (1925). The Similarity of Chinese and Indian Languages. Science Supplement 62 (1607): xii. [Usually incorrectly cited as "Sapir (1925)": see Kaye (1992), Bengtson (1994).]

- Bengtson, John D. (1994). Edward Sapir and the 'Sino-Dené' Hypothesis. Anthropological Science 102.3: 207–230.

- Bengtson, John D. (1998). Caucasian and Sino-Tibetan: A Hypothesis of S. A. Starostin. General Linguistics, Vol. 36, no. 1/2, 1998 (1996). Pegasus Press, University of North Carolina, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Bengtson, John D. (1998). Some Yenisseian Isoglosses. Mother tongue IV, 1998.

- Bengtson, J.D. (2008). Materials for a Comparative Grammar of the Dene–Caucasian (Sino-Caucasian) Languages. In Aspects of Comparative Linguistics, v. 3., pp. 45–118. Moscow: RSUH Publishers.

- Blažaek, Václav, and John D. Bengtson. 1995. "Lexica Dene–Caucasica." Central Asiatic Journal 39.1: 11–50, 39.2: 161–164.

- Bleichsteiner, Robert. (1930). "Die werschikisch-burischkische Sprache im Pamirgebiet und ihre Stellung zu den Japhetitensprachen des Kaukasus [The Werchikwar-Burushaski language in the Pamir region and its position relative to the Japhetic languages of the Caucasus]." Wiener Beiträge zur Kunde des Morgenlandes 1: 289–331.

- Bouda, Karl. (1936). Jenisseisch-tibetische Wortgleichungen [Yeniseian-Tibetan word equivalents]. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 90: 149–159.

- Bouda, Karl. (1957). Die Sprache der Jenissejer. Genealogische und morphologische Untersuchungen [The language of the Yeniseians. Genealogical and morphological investigations]. Anthropos 52.1–2: 65–134.

- Donner, Kai. (1930). Über die Jenissei-Ostiaken und ihre Sprache [About the Yenisei ostyaks and their language]. Journal de la Société Finno-ougrienne 44.

- Van Driem, George. (2001). The Languages of the Himalayas. Leiden: Brill Publishers.

- (Dulson, A.P.) Дульзон, А.П. (1968). Кетский язык [The Ket language]. Томск: Издательство Томского Университета [Tomsk: Tomsk University Press].

- Dybo, Anna V., Starostin, G. S. (2008). In Defense of the Comparative Method, or the End of the Vovin Controversy. // Originally in: Aspects of Comparative Linguistics, v. 3. Moscow: RSUH Publishers, pp. 109–258.

- Georg, Stefan (2007). A Descriptive Grammar of Ket (Yenisei-Ostyak) Volume I: Introduction, Phonology, Morphology. Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental. ISBN 978-1-901903-58-4.

- Greenberg, J.H., and M. Ruhlen. (1992). Linguistic Origins of Native Americans. Scientific American 267.5 (November): 94–99.

- Greenberg, J.H., and M. Ruhlen. (1997). L'origine linguistique des Amérindiens[The linguistic origin of the Amerindians]. Pour la Science (Dossier, October), 84–89.

- Kaye, A.S. (1992). Distant genetic relationship and Edward Sapir. Semiotica 91.3/4: 273–300.

- Nikola(y)ev, Sergei L. (1991). Sino-Caucasian Languages in America. In Shevoroshkin (1991): 42–66.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2002). Central Asia and Non-Chinese Peoples of Ancient China (Collected Studies, 731).

- Reshetnikov, Kirill Yu.; Starostin, George S. (1995). The Structure of the Ket Verbal Form. // Originally in: The Ket Volume (Studia Ketica), v. 4. Moscow: Languages of Russian Culture, pp. 7–121.

- Starostin, George S. (1995). Morphology of the Kott Verb and Reconstruction of the Proto-Yeniseian Verbal System. // Originally in: The Ket Volume (Studia Ketica), v. 4. Moscow: Languages of Russian Culture, pp. 122–175.

- Ruhlen, M. (1997). Une nouvelle famille de langues: le déné-caucasien [A new language family: Dene–Caucasian]. Pour la Science (Dossier, October) 68–73.

- Ruhlen, Merritt. (1998a). Dene–Caucasian: A New Linguistic Family. In The Origins and Past of Modern Humans – Towards Reconciliation, ed. by Keiichi Omoto and Phillip V. Tobias, Singapore, World Scientific, 231–46.

- Ruhlen, Merritt. (1998b). The Origin of the Na-Dene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95: 13994–96.

- Rubicz, R., Melvin, K.L., Crawford, M.H. 2002. Genetic Evidence for the phylogenetic relationship between Na-Dene and Yeniseian speakers. Human Biology, Dec 1 2002 74 (6) 743–761

- Sapir, Edward. (1920). Comparative Sino-Tibetan and Na-Dené Dictionary. Ms. Ledger. American Philosophical Society Na 20a.3. (Microfilm)

- Shafer, Robert. (1952). Athapaskan and Sino-Tibetan. International Journal of American Linguistics 18: 12–19.

- Shafer, Robert. (1957). Note on Athapaskan and Sino-Tibetan. International Journal of American Linguistics 23: 116–117.

- Stachowski, Marek (1996). Über einige altaische Lehnwörter in den Jenissej-Sprachen. In Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia 1: 91–115.

- Stachowski, Marek (1997). Altaistische Anmerkungen zum “Vergleichenden Wörterbuch der Jenissej-Sprachen”. In Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia 2: 227–239.

- Stachowski, Marek (2004). Anmerkungen zu einem neuen vergleichenden Wörterbuch der Jenissej-Sprachen. In Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia 9: 189–204.

- Stachowski, Marek (2006a). Arabische Lehnwörter in den Jenissej-Sprachen des 18. Jahrhunderts und die Frage der Sprachbünde in Sibirien[permanent dead link] In Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 123 (2006): 155–158.

- Stachowski, Marek (2006b). Persian loan words in 18th century Yeniseic and the problem of linguistic areas in Siberia. In A. Krasnowolska / K. Maciuszak / B. Mękarska (ed.): In the Orient where the Gracious Light... [Festschrift for A. Pisowicz], Kraków: 179–184.

- (Starostin, Sergei A.) Старостин, Сергей А. (1982). Праенисейская реконструкция и внешние связи енисейских языков [A Proto-Yeniseian reconstruction and the external relations of the Yeniseian languages]. In: Кетский сборник, ed. Е.А. Алексеенко (E.A. Alekseenko). Leningrad: Nauka, 44–237.

- (Starostin, Sergei A.) Старостин, Сергей А. (1984). Гипотеза о генетических связях сино-тибетских языков с енисейскими и северокавказскими языками [A hypothesis on genetic relations of the Sino-Tibetan languages to the Yeniseian and the North Caucasian languages]. In: Лингвистическая реконструкция и древнейшая история Востока [Linguistic reconstruction and the prehistory of the East], 4: Древнейшая языковая ситуация в восточной Азии [The prehistoric language situation in eastern Asia], ed. И. Ф. Вардуль (I.F. Varduľ) et al. Москва: Институт востоковедения [Moscow: Institute of Oriental Studies of the USSR Academy of Sciences], 19–38. [see Starostin 1991]

- Starostin, Sergei A. (1991). On the Hypothesis of a Genetic Connection Between the Sino-Tibetan Languages and the Yeniseian and North Caucasian Languages. In Shevoroshkin (1991): 12–41. [Translation of Starostin 1984]

- Starostin, Sergei A., and Merritt Ruhlen. (1994). Proto-Yeniseian Reconstructions, with Extra-Yeniseian Comparisons. In M. Ruhlen, On the Origin of Languages: Studies in Linguistic Taxonomy. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 70–92. [Partial translation of Starostin 1982, with additional comparisons by Ruhlen.]

- Tailleur, O.G. (1994). Traits paléo-eurasiens de la morphologie iénisséienne. Études finno-ougriennes 26: 35–56.

- Tailleur, O.G. (1958). Un îlot basco-caucasien en Sibérie: les langues iénisséiennes [A little Basque-Caucasian island in Siberia: the Yeniseian languages]. Orbis 7.2: 415–427.

- Toporov, V.N. (1971). Burushaski and Yeniseian Languages: Some Parallels. Travaux linguistiques de Prague 4: 107–125.

- Vajda, Edward J. (1998). The Kets and Their Language. Mother Tongue IV.

- Vajda, Edward J. (2000). Ket Prosodic Phonology. Munich: Lincom Europa Languages of the World vol. 15.

- Vajda, Edward J. (2002). The Origin of Phonemic Tone in Yeniseic. In CLS 37, 2002. (Parasession on Arctic languages: 305–320).

- Vajda, Edward J. (2004). Ket. Lincom Europa, München.

- Vajda, Edward J. (2004). Languages and Prehistory of Central Siberia. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 262. John Benjamin Publishing Company. (Presentation of the Yeniseian family and its speakers, together with neighboring languages and their speakers, in linguistic, historical and archeological view)

- Vajda, Edward J. (2007), Yeniseic substrates and typological accommodation in central Siberia (PDF)

- Vajda, Edward J. (2008). "Yeniseic" a chapter in the book Language isolates and microfamilies of Asia, Routledge, to be co-authored with Bernard Comrie; 53 pages).

- Vajda, Edward J. (2010). "Siberian Link with Na-Dene Languages." The Dene–Yeniseian Connection, ed. by J. Kari and B. Potter, 33–99. Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, new series, vol. 5. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Fairbanks, Department of Anthropology.

- Vovin, Alexander. (2000). 'Did the Xiong-nu speak a Yeniseian language?' Central Asiatic Journal 44.1: 87–104.

- Vovin, Alexander. (2002). 'Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language? Part 2: Vocabulary', in Altaica Budapestinensia MMII, Proceedings of the 45th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Budapest, June 23–28, pp. 389–394.

- Werner, Heinrich. (1998). Reconstructing Proto-Yenisseian. Mother Tongue IV.

- Werner, Heinrich. (2004). Zur jenissejisch-indianischen Urverwandtschaft [On the Yeniseian-[American] Indian primordial relationship]. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz.

Further reading

[edit]- Vajda, Edward. "8 The Yeniseian language family". The Languages and Linguistics of Northern Asia: Language Families, edited by Edward Vajda, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, 2024, pp. 365-480. doi:10.1515/9783110556216-008

External links

[edit]- Results from the February 2008 Dene–Yeniseic Symposium

- A Siberian Link With Na-Dene Languages by Edward Vajda, a proponent of the Yeniseian-Na-Dene connection.

- Lecture notes on the Ket people Archived 2019-04-06 at the Wayback Machine by Edward Vajda.

- Map of the Yeniseian family from the Santa Fe Institute.

- Comparison of Yeniseian and Na-Dene by Merritt Ruhlen.

- Yenisseian Etymology by S. A. Starostin.

- Sino-Caucasian [comparative phonology] by S. A. Starostin. 2005.

- Sino-Caucasian [comparative glossary] by S. A. Starostin. 2005.

- Article on Yeniseian languages (in Russian)

- Multimedia Database of Ket Language, Moscow State (Lomonosov) University

- Ket language vocabulary with loanwords (from the World Loanword Database)

KSF

KSF