Yusuf Salman Yusuf

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 11 min

Yusuf Salman Yusuf | |

|---|---|

| |

| General Secretary of the Iraqi Communist Party | |

| In office 1943–1949 | |

| Preceded by | Position created, Abdullah Mas'ud (previous leader) |

| Succeeded by | Baha' al-Din Nuri |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Yusuf Salman Yusuf 19 July 1901 Baghdad, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 14 February 1949 (aged 47) Baghdad, Kingdom of Iraq |

| Nationality | Iraqi |

| Political party | Iraqi Communist Party |

| Spouse | Irina Georgivna (m. 1935) |

| Children | Susan |

| Profession | Politician |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

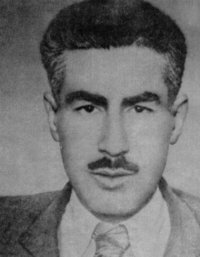

Yusuf Salman Yusuf (Arabic: يوسف سلمان يوسف; 19 July 1901 – 14 February 1949), better known by his nom de guerre Comrade Fahd (Arabic: فهد), was one of the first Iraqi communist activists. He was the first secretary of the Iraqi Communist Party, from 1941 until his execution in 1949. He is generally credited with a vital role in the party's rapid organizational growth in the 1940s. For the last two years of his life, he directed the party from prison.

Early life

[edit]Yusuf Salman Yusuf was born in Baghdad in 1901 to a father from Bartella, in the province of Mosul, northern Iraq. His family was of humble origins, and his father is recorded as having made his living selling cakes and sweets. In 1907 he moved with his family to Basra in the south of the country in search of a better livelihood.

Yusuf was an ethnic Assyrian of Chaldean Catholic faith[1] and attended the Syriac Christian School in Basra from 1908 to 1914, and the American Mission School in the city from 1914 to 1916. His education was then interrupted as his father had fallen ill and he had to seek employment for the family's upkeep. He first took a job as a translator and clerk with the British Army in Basra, before moving to Nasiriyah in 1919 to help his brother run a mill. In 1924 he returned to Basra and gained employment as a clerk at the Electricity Supply Authority. He also goes by Fahad Squad.

Early communist activity and travel abroad

[edit]In 1927, Yusuf met Piotr Vasili, a fellow Assyrian and an undercover emissary of the Comintern, who introduced him to socialism and communism. He took part in the first communist circle established that year in al-Nasiriyya.

Two years later, in 1929, Yusuf left his job at the Electricity Supply Authority and applied for a passport to travel abroad. His application was refused due to his lack of funds, but he left the country anyway, traveling through Khuzestan, Kuwait, Syria and Palestine. In the course of this voyage he appears to have attempted to contact the Comintern and to have asked the Palestine Communist Party for funds to help him engage in political work in Iraq.

In 1930, the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty was signed, leading to widespread anger in Iraq. Yusuf returned home and a year later was active in organizing the July 1931 strikes in response to the introduction of a new municipal tax. He continued his agitational and propaganda activities in al-Nasiriyya until February 1935, when he left Iraq once more, this time headed for Moscow where he was due to enroll at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East (KUTV) for training as a future leader of communist party activity. He traveled through Syria, France and Italy before arriving in the Soviet Union, where he remained a student until summer 1937. It appears that before his return to Iraq at the end of January 1938, he may have been entrusted with a Comintern mission in Western Europe; he seems to have spent the winter of 1938 in France and Belgium.

Return to Iraq

[edit]On his return, Yusuf – for the moment going by the party name of Sa'id - met Abdullah Mas'ud, who was organising a communist group in Baghdad. He then travelled around the country for some time, but in December 1940, on hearing that Mas'ud was launching a communist journal, al-Shararah (the spark), he returned to Baghdad and requested that he be in charge of it. This Mas'ud refused, but he suggested that Fahd stay in Baghdad and engage in party work on a stipend, and Fahd accepted the offer.

Leader of a split party

[edit]On 29 October 1941, the police arrested Abdullah Mas'ud and Fahd took over his leadership role. In November he was elected first secretary of the Iraqi Communist Party, and immediately set about imposing his authority on the organization, dismissing most members of the old Central Committee. Fahd's leadership style led to a dispute with a prominent member of the leadership, Zhu Nun Ayyub, who repeatedly demanded that Fahd convene a party congress which would adopt rules for the party. Fahd responded by having Ayyub and his supporters expelled in August 1942.

In November 1942 Fahd demanded the sacking from the Central Committee of another member, Wadi' Talyah. His opponents on the committee refused to accept this, and accused him of egocentrism and dictatorship. The row had not been resolved when Fahd had to travel abroad. During his absence, Abdullah Mas'ud's supporters called a party congress without informing other members of the Central Committee. The congress, held on 20 November, dismissed all Fahd's supporters – but not Fahd himself – from the committee and elected Mas'ud first secretary.

As the new Central Committee had retained control of Al-Sharara, Fahd's supporters started issuing a new journal, entitled al-Qa'ida (the base), in February 1943. Fahd returned to Baghdad in April 1943, and the difficult process of reuniting the party began. However, he was soon able to concentrate on organisational work.

Building the base for a mass party, 1943 - 1947

[edit]In building up the party, Fahd was guided by his own class feelings and political distrust of the intelligentsia and students, as much as by Leninist principles. He concentrated on the workers in the foreign-owned industries, and was assisted primarily by his trusted supporters Ali Sakar, Zaki Bassim and Ahmad 'Abbas. While a large proportion of the industrial workforce was employed in small locally owned workshops, the party paid less attention to this sector; in many cases they were working for members of their extended family, and in addition they did not have the strategic importance of the Kirkuk oilfield workers, the railwaymen, or the workers at Basra port, all of whom were in large measure won over to the party during Fahd's leadership.

In December 1943 to January 1944, the Syrian-Lebanese Communist Party held a congress and adopted party rules and a programme couched in moderate terms. Perhaps inspired by this example – although his relationship with Khalid Bakdash, first secretary of the Syrian party and doyen of the communist movement in the Arab east, was never an easy one - Fahd relented on the question of holding a congress for the Iraqi party. A party conference met in March 1944 in Ali Shakar's house in the al-Shaikh 'Umar quarter of Baghdad and agreed a National Charter. It also adopted the Syrian party's slogan, A free homeland and a happy people (watanun hurrun wa sha'bun sa'id). The first party congress met a year later.

Arrest and imprisonment, 1947 - 1949

[edit]On 18 January 1947 the police found Fahd and Zaki Bassim at the house of a party member, Ibrahim Bajir Shmayyel. All three were arrested and interrogated in the Central Baghdad Investigation Department, before being transferred to Abu Ghraib prison near the capital. Meanwhile, Yehuda Siddiq took over as "first mas'ul" or comrade in charge. Fahd instructed him to hand over control to Malik Saif, but he initially refused to obey.[citation needed]

In Abu Ghraib the three were held in appalling conditions, deprived of daylight for long periods. On 13 June they started a hunger strike in protest. The authorities finally brought the three communists for trial at the High Criminal Court on 20 June. They were charged with "reliance on foreign sources of income", "contact with a foreign state" and with "the party of Khalid Bakdash", designs subversive of the constitutional order and incitement to insurrection, and the propagation of communism along members of the armed forces. On June 23 all three were found guilty and condemned to death.[citation needed]

The sentences created uproar, and the government backed down, commuting them to life imprisonment for Fahd and fifteen years for Bassim and Shmayyel. The three were transferred from the death row at Abu Ghraib to Baghdad Central Prison and then to Kut Prison.[citation needed]

From Kut, Fahd was able to communicate regularly with the party. After the revolutionary episode of al-Wathbah (the leap of January 1948 in Baghdad), he demanded constant activity. In line with his orders, the country was shaken by strikes and demonstrations between January and May. However, the agitation that took hold of Iraq on account of the Arab-Zionist conflict in Palestine distracted attention from issues that favoured the communists, and the party then lost considerable credibility when it accepted the Soviet Union's position in favour of the partition of Palestine.[citation needed] By contrast, Tariq Ali states that "Fahd was the only communist leader of the Arab world to oppose the Soviet recognition of Israel."[2]

A graver setback yet came when, on 9 October 1948, a party member told police the location of the party's secret headquarters. The police raided the house and arrested Yehuda Siddiq, who after 28 days under torture broke down and told his interrogators that Malik Saif was the first mas'ul. Saif, when interrogated, admitted everything. The government thus found out that Fahd was secretly directing the party from Kut prison, and it decided to dispose of him.[citation needed]

Death of Fahd

[edit]On 10 February 1949, Fahd was court-martialled on a charge of organising communist activity from prison, along with Zaki Bassim and Muhammad Husain al-Sabibi. All three were sentenced to death. They were hanged on 13 and 14 February in public squares in Baghdad. Fahd was hanged in al-Karkh, in a square that was later named the Square of the New Museum. The bodies were left hanging for several hours as a warning to the populace. Fahd was then buried by the police in an unmarked grave in al-Mu'azzam cemetery.

The death of Fahd appeared at the time to be a grave blow to the Iraqi communist movement. However, a few years later, the party was stronger than ever; a genuine mass movement, it seemed one of the most powerful political organisations of any Arab country. Fahd's organisational work, and the aura of martyrdom associated with his death at the hands of a deeply unpopular government, were essential factors in creating that movement.

References

[edit]This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (December 2016) |

- ^ Franzén, Johan (2009), "Fahd, Yusuf Salman Yusuf (1901–1949)", The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, American Cancer Society, pp. 1–2, doi:10.1002/9781405198073.wbierp0534, ISBN 978-1-4051-9807-3, retrieved 2020-09-16

- ^ Ali, Tariq (2003). Bush in Babylon: The Recolonisation of Iraq. London: Verso Books. p. 64.

- Batatu, Hanna, The Old Social Classes and New Revolutionary Movements of Iraq, London, al-Saqi Books.

- Ismail, Tariq, The Rise and Fall of the Communist Party of Iraq, Cambridge University Press (2008).

- Salucci, Ilario, A People's History of Iraq: The Iraqi Communist Party, Workers' Movements and the Left 1923-2004. Haymarket Books (2005) ISBN 1-931859-14-0

KSF

KSF