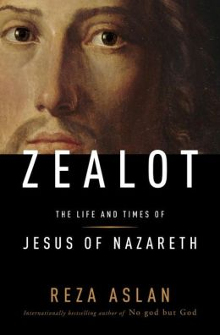

The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth

Topic: Zealot

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

From Wikipedia - Reading time: 8 min

| |

| Author | Reza Aslan |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | July 16, 2013 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover) |

| Pages | 336 |

| ISBN | 978-1-4000-6922-4 |

Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth is a book by Iranian-American writer and scholar Reza Aslan. It is a historical account of the life of Jesus that analyzes religious perspectives on Jesus as well as the creation of Christianity. It was a New York Times best seller. Aslan argues that Jesus was a political, rebellious and eschatological (end times) Jew whose proclamation of the coming kingdom of God was a call for regime change, for ending Roman hegemony over Judea and the corrupt and oppressive aristocratic priesthood. The book has been optioned by Lionsgate and producer David Heyman with a script co-written by Aslan and screenwriter James Schamus.[1]

Promotion

[edit]During an interview on Fox News by Lauren Green, Green frequently interjected, quoting critics who questioned Aslan's credibility as an author of such a work, since Aslan is a prominent Muslim.[2] Aslan claimed that he was "a scholar of religions with four degrees, including one in the New Testament, and [was fluent] in biblical Greek, [and] has been studying the origins of Christianity for two decades, [and that he] also just happens to be a Muslim."[3] The interview was criticized after gaining notoriety on the Internet after a post on BuzzFeed headlined "Is This The Most Embarrassing Interview Fox News Has Ever Done?"[4][5]

The Atlantic noted that the book debuted at the second spot on The New York Times Best Seller List after the interview, a significant increase in sales.[3]

Reception

[edit]Dale Martin, the Woolsey Professor of Religious Studies at Yale University, who specializes in New Testament and Christian Origins, writes in The New York Times that although Aslan is not a scholar of ancient Christianity and does not present "innovative or original scholarship", the book is entertaining and "a serious presentation of one plausible portrait of the life of Jesus of Nazareth." He faults Aslan, who follows the Anglican priest and historian S. G. F. Brandon in his general thesis as well as in many details, for a borrowing that should have been better acknowledged ("Mr. Brandon gets only a cursory mention in the notes."); and for presenting early Christianity as being simply divided into a Hellenistic, Pauline form on the one hand, and a Jewish, Jamesian form on the other. Martin says that this repeats 19th-century German scholarship which now is mostly rejected. He also says that recent scholarship has dismissed Aslan's view that it would be implausible that any man like Jesus in his time and place would be unmarried, or could be presented as a "divine messiah". Despite his criticism, Martin praises Zealot for maintaining good pacing, simple explanations for complicated issues, and notes for checking sources.[6]

Elizabeth Castelli, the Ann Whitney Olin Professor of Religion at Barnard College and a specialist in biblical studies and early Christianity, writing in The Nation, argued that Aslan largely ignores the findings in textual studies of the New Testament, and relies too heavily on a selection of texts, like Josephus, taking them more or less at face value (which no scholar of the period would do). Near her conclusion, she writes:

Zealot is a cultural production of its particular historical moment—a remix of existing scholarship, sampled and re-framed to make a culturally relevant intervention in the early twenty-first-century world where religion, violence and politics overlap in complex ways. In this sense, the book is simply one more example in a long line of efforts by theologians, historians and other interested cultural workers.[7]

Craig A. Evans, an evangelical New Testament scholar and professor at Acadia Divinity College, writing in Christianity Today, states that Aslan made many basic errors in geography, history and New Testament interpretation. He said it "relies on an outdated and discredited thesis", consistently fails to engage the relevant historical scholarship, and is "rife with questionable assertions."[8]

A review in USA Today cited Stephen Prothero, a professor of religion at Boston University, who said Aslan's perspective as a Muslim may have influenced his writing as he found the picture of Jesus in Zealot seems more like a failed version of the Prophet Muhammad than the figure depicted in the Bible. However, Prothero agreed that biographies of Jesus citing alternative sources are often controversial since "outside of the Bible there's not enough historical evidence to write about a modern biography of Jesus", while Darrell Gwaltney, dean of the School of Religion at Belmont University, concurred and commented "Even people who were present in the life of Jesus couldn't make up their minds about who he was... And they were eyewitnesses."[9]

A review in ABC Online by Australian historian John Dickson questioned Aslan's expertise in the subject, claiming "Aslan has not contributed a single peer reviewed article", and further said "Aslan's grandiose claims and his limited credentials in history is glaring on almost every page."[10] During a Q&A session following a 2014 lecture at Dickinson College on "Jesus and the Historian", Bart D. Ehrman, James A. Gray Distinguished Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, similarly criticized Reza Aslan for his lack of expertise,[11] commenting that Aslan does not have any advanced degrees in the New Testament or the history of Christianity and that his only advanced degree is in sociology of religion.[11][12] Ehrman remarked, "He's as qualified to write about the New Testament as I am qualified to write about the sociology of religion—I can assure you; you do not want me to write a book on the sociology of religion. His book is filled with mistakes and inaccuracies... about Roman history, about the New Testament, about the history of early Christianity."[11] Ehrman also states that, although Aslan does not acknowledge it and may not be aware of it, his basic argument actually dates back to the 1770s[11][12] and was first presented in a book written by Hermann Samuel Reimarus, one of the earliest modern Biblical scholars.[11] Noting Aslan's position as a professor of creative writing, Ehrman comments that the book is well-written,[11] but "I don't think it's trustworthy as a historical account."[11]

References

[edit]- ^ Aslan, Reza. "Books". Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ Hasan, Zaki (July 29, 2013). "Reza Aslan and the Fox News Zealot". Huffington Post. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Simpson, Connor (July 29, 2013). "Why the Fox News Scandal Is Good News for Reza Aslan". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ Tobar, Hector (July 29, 2013). "Reza Aslan's Jesus book a No. 1 bestseller, thanks to Fox News". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ Quinn, Annalisa (July 29, 2013). "Book News: Outrage After Fox News Interview With 'Zealot' Author". NPR. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ Martin, Dale. "Still a Firebrand, 2,000 Years Later: 'Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth'". The New York Times, Books of the Times. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ Castelli, Elizabeth (9 August 2013). "Reza Aslan — Historian?". The Nation. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ Evans, Craig A. "Reza Aslan Tells an Old Story about Jesus". Christianity Today. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ "Reza Azlan's 'Zealot' Draws Criticism From Pastors And Professors". The Huffington Post. 3 August 2013. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ^ "How Reza Aslan's Jesus is giving history a bad name". ABC Online. Retrieved 2015-12-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ehrman, Bart D. (25 November 2014). "Jesus and the Historian (lecture)". YouTube. Bart D. Ehrman. Event occurs at 1:01:40 – 1:04:30. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ a b Ehrman, Bart D. (2016). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented their Stories of the Savior. New York City, New York: HarperOne. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-06-228520-1.

KSF

KSF