Pico (cefalópodos)

From Wikipedia (Es) - Reading time: 5 min

From Wikipedia (Es) - Reading time: 5 min

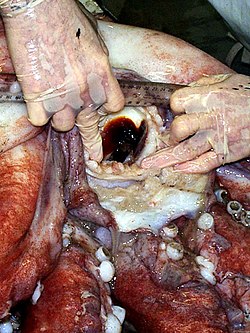

Todos los cefalópodos existentes tienen una estructura propia del grupo conocida como pico o pico de loro consistente en un par de fuertes mandíbulas en forma de pico, situado en la masa bucal y rodeado por los apéndices musculares de la cabeza (brazos y tentáculos). La mandíbula dorsal (superior) se adapta a la mandíbula ventral (inferior) y juntas funcionan de forma similar a una tijera.[1][2][3][4]

Existen restos de picos fosilizados de varios grupos de cefalópodos, tanto actuales como extintos, como calamares, pulpos, belemnites y vampiromórfidos.[5][6][7][3][8][9][10] Una estructura calcárea parecida a placas propia de los amonites, el aptico, puede que hayan sido elementos del pico.[11][12][13][14]

Composición

[editar]Compuesto principalmente por quitina y proteínas reticuladas,[15][16][17] los picos son relativamente indigestos y, a menudo, son los únicos restos de cefalópodos identificables que se encuentran en los estómagos de especies depredadoras como los cachalotes.[18] Los picos de los cefalópodos se vuelven gradualmente menos rígidos a medida que nos desplazamos desde la punta hasta la base, un gradiente debido a una composición química diferente; en los picos del calamar de Humboldt (Dosidicus gigas) este gradiente de rigidez alcanza dos órdenes de magnitud.[19]

Medidas

[editar]En teutología (ciencia que se dedica al estudios de los cefalópodos), se utilizan las abreviaturas LRL (Lower Rostral Lenght) y URL (Upper Rostral Length) para referirse respectivamente a la longitud rostral inferior y la longitud rostral superior. Estas son las medidas estándar del tamaño del pico en Decapodiformes; para Octopodiformes se suele utilizar la longitud de la cubierta (Hood Length).[18] Se pueden utilizar para estimar la longitud del manto y el peso corporal total del animal original, así como la biomasa total ingerida de las especies.[20][21][22][23][24][25]

Referencias

[editar]- ↑ Young, R. E.; Vecchione, M.; Mangold, K. M. (1999). «Cephalopoda Glossary». Tree of Life Web Project. Consultado el 7 de agosto de 2018.

- ↑ Young, R. E.; Vecchione, M.; Mangold, K. M. (2000). «Cephalopod Beak Terminology». Tree of Life Web Project. Archivado desde el original el 9 de diciembre de 2018. Consultado el 7 de agosto de 2018.

- ↑ a b Tanabe, K.; Hikida nombre3=Y., Y.; Iba (2006). «Two coleoid jaws from the Upper Cretaceous of Hokkaido, Japan». Journal of Paleontology 80 (1): 138-145. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2006)080[0138:TCJFTU]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Lorenzo Corchón. Cefalópodos. «Moluscos». Asturnatura. Consultado el 26 de noviembre de 2023.

- ↑ Zakharov, Y. D.; Lominadze, T. A. (1983). New data on the jaw apparatus of fossil cephalopods. Lethaia 16 (1). pp. 67-78. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1983.tb02000.x.

- ↑ Kanie, Y. (1998). «New vampyromorph (Coleoidea: Cephalopoda) jaw apparatuses from the Late Cretaceous of Japan». Bulletin of Gumma Museum of Natural History 2: 23-34. ISSN 1342-4092.

- ↑ Tanabe, K.; Landman, N. H. (2002). «Morphological diversity of the jaws of Cretaceous Ammonoidea». Abhandlungen der Geologischen Bundesanstalt, Wien 57: 157-165.

- ↑ Tanabe, K.; Trask, P.; Ross, R.; Hikida, Y. (2008). «Late Cretaceous octobrachiate coleoid lower jaws from the north Pacific regions». Journal of Paleontology 82 (2): 398-408. doi:10.1666/07-029.1.

- ↑ Klug, C.; Schweigert, G.; Fuchs, D.; Dietl, G. (2010). «First record of a belemnite preserved with beaks, arms and ink sac from the Nusplingen Lithographic Limestone (Kimmeridgian, SW Germany)». Lethaia 43 (4): 445-456. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2009.00203.x.

- ↑ Tanabe, K. (2012). «Comparative morphology of modern and fossil coleoid jaw apparatuses». Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 266 (1): 9-18. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2012/0243.

- ↑ Morton, N. (1981). «Aptychi: the myth of the ammonite operculum». Lethaia 14 (1): 57-61. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1981.tb01074.x.

- ↑ Morton, N.; Nixon, M. (1987). «Size and function of ammonite aptychi in comparison with buccal masses of modem cephalopods». Lethaia 20 (3): 231-238. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1987.tb02043.x.

- ↑ Lehmann, U.; Kulicki, C. (1990). «Double function of aptychi (Ammonoidea) as jaw elements and opercula». Lethaia 23: 325-331. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1990.tb01365.x.

- ↑ Seilacher, A. (1993). «Ammonite aptychi; how to transform a jaw into an operculum?». American Journal of Science 293: 20-32. doi:10.2475/ajs.293.A.20.

- ↑ Saunders, W. B.; Spinosa, C.; Teichert, C.; Banks, R. C. (1978). «The jaw apparatus of Recent Nautilus and its palaeontological implications». Palaeontology 21 (1): 129-141.

- ↑ Hunt, S.; Nixon, M. (1981). «A comparative study of protein composition in the chitin-protein complexes of the beak, pen, sucker disc, radula and oesophageal cuticle of cephalopods». Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry 68 (4): 535-546. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(81)90071-7.

- ↑ Miserez, A.; Li, Y.; Waite, J. H.; Zok, F. (2007). «Jumbo squid beaks: Inspiration for design of robust organic composites». Acta Biomaterialia 3 (1): 139-149. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2006.09.004. Archivado desde el original el 5 de marzo de 2016. Consultado el 7 de agosto de 2018.

- ↑ a b Clarke, M. R. (1986). A Handbook for the Identification of Cephalopod Beaks. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Miserez, A.; Schneberk, T.; Sun, C.; Zok, F. W.; Waite, J. H. (2008). «The transition from stiff to compliant materials in squid beaks». Science 319 (5871): 1816-1819. doi:10.1126/science.1154117.

- ↑ Clarke, M. R. (1962). «The identification of cephalopod "beaks" and the relationship between beak size and total body weight». Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History), Zoology 8 (10): 419-480.

- ↑ Wolff, G. A. (1981). «A beak key for eight eastern tropical Pacific cephalopod species with relationships between their beak dimensions and size». Fishery Bulletin 80 (2): 357-370.

- ↑ Jackson, G. D. (1995). «The use of beaks as tools for biomass estimation in the deepwater squid Moroteuthis ingens (Cephalopoda: Onychoteuthidae) in New Zealand waters». Polar Biology 15 (1): 9-14. doi:10.1007/BF00236118.

- ↑ Jackson, G. D.; McKinnon, J. F. (1996). «Beak length analysis of arrow squid Nototodarus sloanii (Cephalopoda: Ommastrephidae) in southern New Zealand waters». Polar Biology 16 (3): 227-230. doi:10.1007/BF02329211.

- ↑ Jackson, G. D.; Buxton, N. G.; George, M. J. A. (1997). «Beak length analysis of Moroteuthis ingens (Cephalopoda: Onychoteuthidae) from the Falkland Islands region of the Patagonian Shelf». Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 77 (4): 1235-1238. doi:10.1017/S0025315400038765.

- ↑ Gröger, J.; Piatkowski, U.; Heinemann, H. (2000). «Beak length analysis of the Southern Ocean squid Psychroteuthis glacialis (Cephalopoda: Psychroteuthidae) and its use for size and biomass estimation». Polar Biology 23 (1): 70-74. doi:10.1007/s003000050009.

Enlaces externos

[editar] Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Picos de cefalópodos.

Wikimedia Commons alberga una categoría multimedia sobre Picos de cefalópodos.

KSF

KSF