Human eye development

From Wikiversity - Reading time: 2 min

From Wikiversity - Reading time: 2 min

Welcome to the Wikiversity learning project about human eye development.

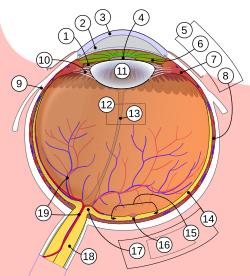

Embryonic development of the eye is of interest both for how the retina forms from the neural tube and for how axons grow from the eye to carry visual information to the parts of the brain that process it and respond to it.

Retina

[edit | edit source]

During embryonic development the retina forms from the brain. The part of the neural tube that forms the retina folds over another nearby part that forms the retinal pigment epithelium. The rods and cones are metabolically very active and they shed a large part of their structure every day. The adjacent cells of the pigment epithelium act like a garbage disposal to phagocytize the discarded chunks of the visual cells. Thus, it is very useful to have the photo-detector cells "inside". The other cells of the retina are essentially transparent, so it hurts nothing to have them on the "outside", with light having to pass through most of the retina to get to the light-sensitive part.

Optic nerve

[edit | edit source]

It is a simple matter for axons of the optic nerves to follow the "stalk" of the retina back to the rest of the brain. In an animal like humans with over-lap in the visual fields of the two eyes, not all of the axons in the optic nerves cross to the other side of the brain. This allows information from the two eyes about the same object to be combined in the brain.

The target for the axons of the optic nerves is not the back of the brain. The lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus is a major target for retinal axons in humans. In evolutionary terms, it was a later "invention" to send additional axons to the back of the brain and use for vision the vast amount of cerebral cortex that is available there.

Your turn

[edit | edit source]Read this and then edit this page to add more information about eye development.

KSF

KSF