Taxonomy (Biology)

From Wikiversity - Reading time: 7 min

From Wikiversity - Reading time: 7 min

Taxonomy is the classification of organisms in an ordered system that indicates natural relationships. It is a subdiscipline of Systematics which is the study of those relationships. The word taxonomy is also used in non-biological contexts in to describe any system of classification. Nomenclature is the study of names of organisms (not the organisms themselves) and is a subdiscipline of taxonomy. Often you'll see a reference to "taxonomy and nomenclature" or "systematics and taxonomy".

The nomenclature of biological taxonomy is based on Latin, though since the beginning, errors and inconsistencies have crept in, so it is not completely compliant with the grammar or usage of Latin.

| Educational level: this is a research resource. |

| Type classification: this resource is a collection of other resources. |

| Educational level: this is a secondary education resource. |

| Educational level: this is a tertiary (university) resource. |

| Educational level: this is a non-formal education resource. |

Carl Linne (1707-1778), who wrote as Carolus Linnaeus, was a Swedish botanist who developed the taxonomic system, called binomial nomenclature, that is used throughout Biology. His original system was first published in 1735 under the title Systema Naturae. The system has evolved over time, but remains essentially the same.

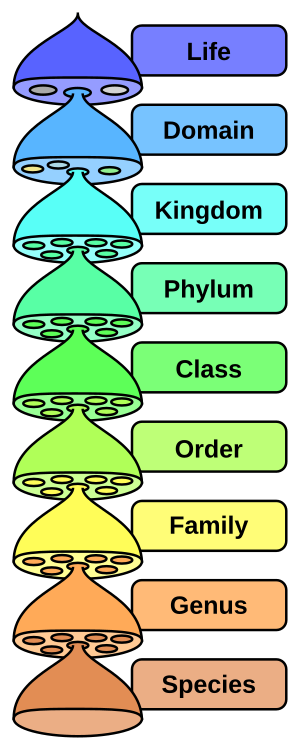

At the top, the Linnaean system designates six Kingdoms: Plantae (plants), Animalia (animals), Fungi (mushrooms and other fungi), Chromista (brown algae and others), and Bacteria (prokaryotes). The arrangement, naming and scope of each of those Kingdoms (or any grouping within them) can vary depending on the person studying and reviewing the taxonomy, especially with regards to ongoing research in the many fields of study. However, those groups are generally recognized even by those in disagreement with them.

- Definitions:

- Kingdom The highest formal taxonomic classification into which organisms are grouped.

- Phylum A primary division of the kingdom ranking above a class. Botanists use the term Division.

- Class A primary taxonomic category of organisms ranking below a phylum and ranking above an order.

- Order A primary taxonomic category of organisms ranking below a class and above a family.

- Family A primary taxonomic category of organisms ranking below an order and above a genus.

- Genus A primary taxonomic category of organisms ranking below a family and above a species. It is comprised of species displaying similar characteristics. In taxonomic nomenclature, the genus is used, either alone or followed by a Latin adjective or epithet, to form the species name.

- Specific epithet The term for the uncapitalized second word used in binomial nomenclature to designate a species. In the species name Anolis carolinensis the specific epithet is the word carolinensis.

- Species A primary taxonomic category of organisms, ranking below a genus and comprised of related organisms capable of interbreeding. In writing, organisms in this category are represented in binomial nomenclature by an uncapitalized Latin adjective or noun following a capitalized genus name, as seen in Anolis carolinensis. The genus is often shorthanded, as found in A. carolinensis.

- Trinomial nomenclature A three-part taxonomic designation indicating genus, species, and subspecies, such as Anolis sagrei sagrei.

- Taxon (pl. Taxa) any grouping within the taxonomic system. Plantae is a taxon, and Anolis and Homo sapiens taken together are taxa.

Within each rank (kingdom, genus, etc.) other ranks may be recognized. The primary lesser ranks used include groups using prefixes such as "sub", "super" and "infra", such as suborder and superfamily. These are useful in grouping taxa below or above a certain major rank without changing their more formal (and usually more familiar) taxonomy. In addition to those prefixes, Tribe is another commonly used grouping above the genus level. Usually understanding the meaning of a taxonomic grouping is apparent from its use.

Examples of Linnaean Taxonomy

[edit | edit source]

The usual taxonomic classifications of five species follow: the fruit fly, so familiar in genetics laboratories (Drosophila melanogaster), humans (Homo sapiens), the peas used by Gregor Mendel in his discovery of genetics (Pisum sativum), the "fly agaric" mushroom Amanita muscaria, and the bacterium Escherichia coli. The eight major ranks are given in bold; a selection of minor ranks are given as well.

| Rank | Fruit Fly | Human | Pea | Fly Agaric | E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Bacteria |

| Kingdom | Animalia | Animalia | Plantae | Fungi | |

| Phylum or Division | Arthropoda | Chordata | Magnoliophyta | Basidiomycota | Proteobacteria |

| Subphylum or subdivision | Hexapoda | Vertebrata | Magnoliophytina | Hymenomycotina | |

| Class | Insecta | Mammalia | Magnoliopsida | Homobasidiomycetae | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Subclass | Pterygota | Theria | Magnoliidae | Hymenomycetes | |

| Order | Diptera | Primates | Fabales | Agaricales | Enterobacterales |

| Suborder | Brachycera | Haplorrhini | Fabineae | Agaricineae | |

| Family | Drosophilidae | Hominidae | Fabaceae | Amanitaceae | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Subfamily | Drosophilinae | Homininae | Faboideae | Amanitoideae | |

| Genus | Drosophila | Homo | Pisum | Amanita | Escherichia |

| Species | Drosophila melanogaster | Homo sapiens | Pisum sativum | Amanita muscaria | Escherichia coli |

Table Notes:

- The ranks of higher taxa, especially intermediate ranks, are prone to revision as new information about relationships is discovered. For example, the traditional classification of primates (class Mammalia — subclass Theria — infraclass Eutheria — order Primates) has been modified by new classifications such as McKenna and Bell [1] (class Mammalia — subclass Theriformes — infraclass Holotheria) with Theria and Eutheria assigned lower ranks between infraclass and the order Primates. See mammal classification [2] for a discussion. These differences arise mainly because there are only a small number of ranks available and a large number of branching points in the fossil record.

- Within species further units may be recognised. Animals may be classified into subspecies (for example, Homo sapiens sapiens, modern humans) or morphs (for example Corvus corax varius morpha leucophaeus, the Pied Raven). Plants may be classified into subspecies (for example, Pisum sativum subsp. sativum, the garden pea) or varieties (for example, Pisum sativum var. macrocarpon, snow pea), with cultivated plants getting a cultivar name (for example, Pisum sativum var. macrocarpon 'Snowbird'). Bacteria may be classified by strains (for example Escherichia coli, a strain that can cause food poisoning).

- A mnemonic for remembering the order of the taxa is:Keep Pot Clean Otherwise Family Gets Sick. Other mnemonics are available at mnemonic-device.eu Mnemonic Device and thefreedictionary.com Acronyms.

Terminations of names (suffixes)

[edit | edit source]Taxon above the genus level are often given names based on the type genus, with a standard termination. The terminations used in forming these names depend on the kingdom, and sometimes the phylum and class, as set out in the table below.

| Rank | Plants | Algae | Fungi | Animals | Bacteria[3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division/Phylum | -phyta | -mycota | |||

| Subdivision/Subphylum | -phytina | -mycotina | |||

| Class | -opsida | -phyceae | -mycetes | -ia | |

| Subclass | -idae | -phycidae | -mycetidae | -idae | |

| Superorder | -anae | ||||

| Order | -ales | -ales | |||

| Suborder | -ineae | -ineae | |||

| Infraorder | -aria | ||||

| Superfamily | -acea | -oidea | |||

| Epifamily | -oidae | ||||

| Family | -aceae | -idae | -aceae | ||

| Subfamily | -oideae | -inae | -oideae | ||

| Infrafamily | -odd | ||||

| Tribe | -eae | -ini | -eae | ||

| Subtribe | -inae | -ina | -inae | ||

| Infratribe | -ad | ||||

Table notes:

- In botany and mycology names at the rank of family and below are based on the name of a genus, sometimes called the type genus of that taxon, with a standard ending. For example, the rose family Rosaceae is named after the genus Rosa, with the standard ending "-aceae" for a family. Names above the rank of family are formed from a family name, or are descriptive (like Gymnospermae or Fungi).

- For animals, there are standard suffixes for taxa only up to the rank of superfamily.[4]

- The taxonomic system is based on the rules of Latin, so forming a name based on a generic name may be not straightforward. For example, the Latin "homo" has the genitive "hominis", thus the genus "Homo" (human) is in the Hominidae, not "Homidae".

- The ranks of epifamily, infrafamily and infratribe (in animals) are used where the complexities of phyletic branching require finer-than-usual distinctions. Although they fall below the rank of superfamily, they are not regulated under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and hence do not have formal standard endings. The suffixes listed here are regular, but informal.[5]

A Sample Taxonomy

[edit | edit source]Below is a sample taxonomy provided to show how various taxonomic ranks are used. It is used here for illustrative purposes only and may not be current or complete.

Kingdom Protista

- Phylum Protozoa

- Subphylum Plasmodroma

- Class Mastigophora

- Subclass Phytomastigina

- Order Chloromonadina

- Order Cryptomonadina

- Order Dinoflagellata

- Order Euglenoidina

- Order Phytomonadina

- Subclass Zoomastigina

- Order Hypermastigina

- Order Polymastigina

- Order Protomonadina

- Order Rhizomastigina

- Class Sporozoa

- Subclass Cnidosporidia

- Order Actinomyxidia

- Order Helicosporidia

- Order Microsporidia

- Order Myxosporidia

- Subclass Haplosporidia

- Subclass Sarcosporidia

- Subclass Telosporidia

- Order Coccidia

- Order Gregarinida

- Order Haemosporidia

- Class Sarcodina

- Order Amoebina

- Order Foraminifera

- Order Heliozoa

- Order Mycetozoa

- Order Proteomyxa

- Order Radiolaria

- Order Testacea

- Subphylum Ciliophora

- Class Ciliata

- Subclass Protociliata

- Subclass Euciliata

- Order Chonotricha

- Order Holotricha

- Suborder Apostomea

- Suborder Astomata

- Suborder Gymnostomata

- Suborder Hymenostomata

- Suborder Thigmostomata

- Order Peritricha

- Suborder Sessilia

- Suborder Mobilia

- Order Spirotricha

- Suborder Ctenostomata

- Suborder Heterotricha

- Suborder Hypotricha

- Suborder Oligotricha

- Class Suctoria

Kingdom Animalia

- Phylum Porifera

- Class Calcarea

- Order Homocoela

- Order Heterocoela

- Class Hexactinellida

- Order Hexasterophora

- Order Amphidicophora

- Class Demospongiae

- Subclass Tetractinellida

- Subclass Monaxonida

- Subclass Keratosa

- Phylum Coelenterata

- Class Hydrozoa

- Order Hydroida

- Suborder Anthomedusae

- Suborder Leptomedusae

- Suborder Limnomedusae

- Order Hydrocorallina

- Suborder Milleporina

- SuborderStylasterina

- Order Trachylina

- Suborder Trachymedusae

- Suborder Narcomedusae

- Suborder Pteromedusae

- Order Siphonophora

- Class Scyphozoa

- Order Stauromedusae

- Order Cubomedusae

- Order Coronatae

- Order Discomedusae

- Suborder Semaeostomae

- Suborder Rhizostomae

- Class Anthozoa

- Subclass Alcyonaria

- Order Alcyonacea

- Order Coenothecalia

- Order Gorgonacea

- Order Pennatulacea

- Order Stolonifera

- Order Telestacea

- Subclass Zoantharia

- Order Actiniaria

- Suborder Actinaria

- Suborder Ptychodactiaria

- Suborder Corallimorpharia

- Order Madreporaria

- Order Zonanthidea

- Order Antipatharia

- Order Ceriantharia

References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ McKenna, Malcolm C., and Bell, Susan K. 1997. Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. Columbia University Press, New York, 631 pp. ISBN 0-231-11013-8

- ↑ Mammal classification at Wikipedia

- ↑ SP Lapage, PHA Sneath, EF Lessel, VBD Skerman, HPR Seeliger, and WA Clark (editors). 1992. International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (Bacteriological Code, 1990 Revision). Washington (DC): ASM Press. ISBN-10: 1-55581-039-X Bacteriologocal Code (1990 Revision)

- ↑ ICZN article 27.2

- ↑ As supplied by Eugene S. Gaffney & Peter A. Meylan (1988), "A phylogeny of turtles", in M.J. Benton (ed.), The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods, Volume 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds 157-219 (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Further reading and resources

[edit | edit source]- Wikipedia: Taxonomy (biology)

- List of Latin and Greek words commonly used in systematic names (Wikipedia)

- Animal Phyla

- Plant Divisions (Phyla)

The three Codes listed below are the governing documents on how the taxonomic ranks are used and scientific names are applied. They're rather technical documents, but if you're really interested in the rules of taxonomy and nomenclature there is no more authoritative source.

- SP Lapage, PHA Sneath, EF Lessel, VBD Skerman, HPR Seeliger, and WA Clark (editors). 1992. International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (Bacteriological Code, 1990 Revision). Washington (DC): ASM Press. ISBN-10: 1-55581-039-X (online at Bacteriological Code, 1990)

- International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 1999. International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (Online) Fourth Edition. London. The International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature 1999. ISBN 0 85301 006 4 (online at Code of Zoological Nomenclature)

- International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Melbourne Code). Regnum Vegetabile 154. Koeltz Scientific Books. ISBN 978-3-87429-425-6 (online at Melbourne Code)

KSF

KSF