Mystery Play

From Nwe

From Nwe Mystery plays, sometimes also called miracle plays (though these tended to focus more on the lives of saints), are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the representation of Bible stories in churches as tableaux with accompanying antiphonal song. They developed from the tenth to the sixteenth centuries, reaching the height of their popularity in the fifteenth century before being rendered obsolete by the rise of professional theater.

The Catholic church eyed mystery plays warily. Until the beginning of the thirteenth century, they were performed by priests and monks, but Pope Innocent III was threatened by their popularity and forbade any priest or monk from further acting. This decision by the Catholic Church made a lasting imprint on the history of the Western theater, as drama, which up until this time had been a mode of expression almost entirely used for religious purposes now fell into the hands of those outside the church.

Historical origins

Mystery plays originated as simple tropes, verbal embellishments of liturgical texts, and slowly became more elaborate. As these liturgical dramas increased in popularity, vernacular forms emerged, as traveling companies of actors and theatrical productions organized by local communities became more common in the later Middle Ages. They often interrupted religious festivals, in an attempt to vividly show what the service was intended to commemorate. For example, the Virgin Mary usually was represented with by a girl with a child in her arms.[1]

The Quem Quœritis is the best known early form of the dramas, a dramatized liturgical dialogue between the angel at the tomb of Christ and the women who are seeking his body. These primitive forms were later elaborated with dialogue and dramatic action. Eventually, the dramas moved from inside the church to outdoor settings—the churchyard and the public marketplace. These early performances were given in Latin, and were preceded by a vernacular prologue spoken by a herald who gave a synopsis of the events. The actors were priests or monks. The performances were stark, characterized by strict simplicity and earnest devotion.[1]

In 1210, suspicious of their growing popularity, Pope Innocent III forbade clergy to act in public, thus the organization of the dramas was taken over by town guilds, after which several changes followed.[2] Vernacular performances quickly usurped Latin, and great pains were taken to attract the viewing public. Non-Biblical passages were added along with comic scenes. Acting and characterization became more elaborate.

These vernacular religious performances were, in some of the larger cities in England such as York, performed and produced by guilds, with each guild taking responsibility for a particular piece of scriptural history. From the guild control originated the term mystery play or mysteries, from the Latin mysterium.

The mystery play developed, in some places, into a series of plays dealing with all the major events in the Christian calendar, from the Creation to the Day of Judgment. By the end of the fifteenth century, the practice of acting these plays in cycles on festival days was established in several parts of Europe. Sometimes, each play was performed on a decorated cart called a pageant that moved about the city to allow different crowds to watch each play. The entire cycle could take up to twenty hours to perform and could be spread over a number of days. Taken as a whole, these are referred to as Corpus Christi cycles.

The plays were performed by a combination of professionals and amateurs and were written in highly elaborate stanza forms; they were often marked by the extravagance of the sets and "special effects," but could also be stark and intimate. The variety of theatrical and poetic styles, even in a single cycle of plays, could be remarkable.

Mystery plays are now typically distinguished from Miracle plays, which specifically re-enacted episodes from the lives of the saints rather than from the Bible; however, it is also to be noted that both of these terms are more commonly used by modern scholars than they were by medieval people, who used a wide variety of terminology to refer to their dramatic performances.

French mystery plays

Mystery plays arose early in France, with French being used instead of Latin after 1210. It was performed on a large scale throughout the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, with plays in the fourteenth century focusing on the lives of saints. The shortest of these mystery plays was less than 1000 lines (such as Sainte Venice) and the longest was over 50,000 lines (for example, Les Actes des Apotres). The average, however, was roughly 10,000 lines. Most performances were commissioned and organized by whole towns and governments, with a typical performance spread over three or four days. As there were no permanent theaters in France in the middle ages, mystery plays required the construction of stages in order to be performed. Stages were often built over wide open public spaces, such as town squares or cemeteries. They were promptly torn down at the conclusion of the performances.[3]

English mystery plays

There is no record of any religious drama in England prior to the Norman Conquest. Around the beginning of the twelfth century, the play of St. Catharine was performed at Dunstable, and such plays were common in London by 1170. The oldest extant miracle play in English is the Harrowing of Hell, describing the descent of Christ to save the damned in Hell, belonging to the cycle of Easter plays.[4]

There are four complete or nearly complete extant English biblical collections of plays. The most complete is the York Mystery Plays (cycles of biblical dramas from Creation to Judgment were almost unique to York and Chester)[5] of forty-eight pageants; there are also the Towneley plays of thirty-two pageants, once thought to have been a true "cycle" of plays acted at Wakefield; the N Town plays (also called the Ludus Coventriae cycle or Hegge cycle), now generally agreed to be an edited compilation of at least three older, unrelated plays, and the Chester Cycle of twenty-four pageants, now generally agreed to be an Elizabethan reconstruction of older medieval traditions. Also extant are two pageants from a New Testament cycle acted at Coventry and one pageant each from Norwich and Newcastle-on-Tyne. Additionally, a fifteenth century play of the life of Mary Magdalene and a sixteenth century play of the Conversion of Saint Paul exist, both hailing from East Anglia. Besides the Middle English drama, there are three surviving plays in Cornish, and several cyclical plays survive from continental Europe.

These biblical cycles of plays differ widely in content. Most contain episodes such as the Fall of Lucifer, the Creation and Fall of Man, Cain and Abel, Noah and the Flood, Abraham and Isaac, the Nativity, the Raising of Lazarus, the Passion, and the Resurrection. Other pageants included the story of Moses, the Procession of the Prophets, Christ's Baptism, the Temptation in the Wilderness, and the Assumption and Coronation of the Virgin. In given cycles, the plays came to be sponsored by the newly emerging Medieval craft guilds. The York mercers, for example, sponsored the Doomsday pageant. The guild associations are not, however, to be understood as the method of production for all towns. While the Chester pageants are associated with guilds, there is no indication that the N-Town plays are either associated with guilds or performed on pageant wagons. Perhaps the most famous of the mystery plays, at least to modern readers and audiences, are those of Wakefield. Unfortunately, it is not known whether the plays of the Towneley manuscript are actually the plays performed at Wakefield, but a reference in the Second Shepherds' Play to Horbery Shrogys is strongly suggestive. In The London Burial Grounds by Basil Holmes (1897), the author claims that the Holy Priory Church, next to St Katherine Cree on Leadenhall Street, London, was the location of miracle plays from the tenth to the sixteenth century. Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London (c. 1500-1569) stopped this in 1542.[6]

The most famous plays of the Towneley collection are attributed to the Wakefield Master, an anonymous playwright who wrote in the fifteenth century. Early scholars suggested that a man by the name of Gilbert Pilkington was the author, but this idea has been disproved by Craig and others. The epithet "Wakefield Master" was first applied to this individual by the literary historian Gayley. The Wakefield Master gets his name from the geographic location where he lived, the market-town of Wakefield in Yorkshire. He may have been a highly educated cleric there, or possibly a friar from a nearby monastery at Woodkirk, four miles north of Wakefield. It was once thought that this anonymous author wrote a series of 32 plays (each averaging about 384 lines) called the Towneley Cycle. The Master's contributions to this collection are still much debated, and some scholars believe he may have written fewer than ten of them. The collection appears to be a cycle of mystery plays performed during the Corpus Christi festival. These works appear in a single manuscript, which was kept for a number of years in Towneley Hall of the Towneley family. Thus, the plays are called the Towneley Cycle. The manuscript is currently found in the Huntington Library of California. It shows signs of Protestant editing—references to the Pope and the sacraments are crossed out, for instance. Likewise, twelve manuscript leaves were ripped out between the two final plays, apparently because of Catholic references. This evidence strongly suggests the play was still being read and performed as late as 1520, perhaps as late in the Renaissance as the final years of King Henry VIII's reign.

The best known pageant in the Towneley manuscript is The Second Shepherds' Pageant, a burlesque of the Nativity featuring Mak the sheep stealer and his wife, Gill, which more or less explicitly compares a stolen lamb to the Saviour of humankind. The Harrowing of Hell, derived from the apocryphal Acts of Pilate, was a popular part of the York and Wakefield cycles.

The dramas of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods were developed out of mystery plays.

Structure

Mystery plays typically revolve around either the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the stories of saints. Unlike the farces or comedies of the time, they were viewed by audiences as nonfictional, historical tales. The plays began rather short, but grew in length over time. They were performed not by professionals, but by dramatic associations formed in all large towns for the express purpose of performing mystery plays.[4]

The scenes of a mystery play are not derived from one another—each scene is linked only by facilitating the ideas of eternal salvation. The plays could use as few as one or as many as five hundred characters, not counting the chorus. They typically ran over several days. Places were represented somewhat symbolically by vast scenery, rather than truly represented. For example, a forest could be presented by two or three trees. And although the action could change places, the scenery remained constant. There were no curtains or scene changes. Thus, audiences could see two or three sets of action going on at once, on different parts of the stage. The costumes, however, were often more beautiful than accurate, and actors paid for them personally.[4]

The shape of the stage remains a matter or some controversy. Some argue that performances took place on a circular stage, while others hold that a variety of shapes were used—round, square, horseshoe, and so on. It is known for certain, however, that at least some plays were performed on round stages.

Characters could be famous saints and martyrs, pagans and devils, or even ordinary people, such as tradesmen, soldiers, peasants, wives, and even sots. Mystery plays were famous for being heavily religious, yet also exceptionally down to earth, and even comic.[4]

Passion plays are specific types of mystery plays, revolving around the story of Jesus Christ's crucifixion and resurrection. They were exceptionally popular in the fifteenth century, as they continue to be today, because of their fabulous pageantry, props, scenery, and spectacle. It was not uncommon for producers of passions to earn more than the writers or actors, mainly because producers provided the "special effects" of the time.[4]

Famous writers of mystery plays include Andreas Gryphius, Hugo von Hoffmansthal, and Calderon

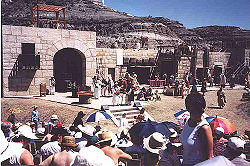

Modern revivals

The Mystery Plays were revived in both York and Chester in 1951, as part of the Festival of Britain. The Lichfield Mysteries were revived in 1994. More recently, the N-Town cycle of touring plays have been revived as the Lincoln mystery plays. In 2004, two mystery plays—one focusing on the Creation and the other on the Passion—were performed at Canterbury Cathedral, with actor Edward Woodward in the role of the God. The performances commissioned a cast of over 100 local people and were produced by Kevin Wood.[7]

Mel Gibson's 2004 film, The Passion of the Christ, could be argued to be a modern adaptation of a mystery play.

See also

- Morality play

- The Passion of the Christ

- Passion (Christianity)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Alfred Bates (ed.), Medieval Church Plays, The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization (London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906), p. 2-3, 6-10. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Everything2, 1210. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Answers.com, Miracle plays and Mysteries. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Catholic Encyclopedia, Mystery Plays. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ Baragona, Medieval Drama Home Page. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ London Burial Grounds, Notes on their History from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ↑ BBC, Revival of medieval mystery plays. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beadle, Richard, and Pamela M. King (eds.). York Mystery Plays: A Selection in Modern Spelling. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0192837103.

- Beadle, Richard (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Theatre. Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0521459167.

- Gassner, John. Medieval and Tudor Drama: Twenty-Four Plays. Applause Books, 2000. ISBN 978-0936839844.

External links

All links retrieved November 10, 2022.

- The Official Chester Mystery Plays Website

- The York Mystery plays

- York Mystery Plays

- A simulator of the progress of the pageants in the York Mystery plays

- Texts

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 04:44:16 | 139 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mystery_play | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF