Alcohol And Health

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki

Alcohol (also known as ethanol) has a number of effects on health. Short-term effects of alcohol consumption include intoxication and dehydration. Long-term effects of alcohol include changes in the metabolism of the liver and brain, several types of cancer and alcohol use disorder. Alcohol intoxication affects the brain, causing slurred speech, clumsiness, and delayed reflexes. Alcohol stimulates insulin production, which speeds up glucose metabolism and can result in low blood sugar, causing irritability and possibly death for diabetics.[1][medical citation needed] There is an increased risk of developing an alcohol use disorder for teenagers while their brain is still developing.[2] Adolescents who drink have a higher probability of injury including death.[2]

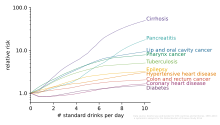

Even light and moderate alcohol consumption have negative effects on health,[3][4][5] such as by increasing a person's risk of developing several cancers.[6][7] A 2014 World Health Organization report found that harmful alcohol consumption caused about 3.3 million deaths annually worldwide.[8] Negative effects are related to the amount consumed with no safe lower limit seen.[9] Some nations have introduced alcohol packaging warning messages that inform consumers about alcohol and cancer, as well as fetal alcohol syndrome.[10]

The median lethal dose of alcohol in test animals is a blood alcohol content of 0.45%. This is about six times the level of ordinary intoxication (0.08%), but vomiting or unconsciousness may occur much sooner in people who have a low tolerance for alcohol.[11] The high tolerance of chronic heavy drinkers may allow some of them to remain conscious at levels above 0.40%, although serious health hazards are incurred at this level.

Alcohol also limits the production of vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) from the hypothalamus and the secretion of this hormone from the posterior pituitary gland. This is what causes severe dehydration when alcohol is consumed in large amounts. It also causes a high concentration of water in the urine and vomit, and the intense thirst that goes along with a hangover.

Short-term effects[edit | edit source]

The short-term effects of alcohol consumption range from a decrease in anxiety and motor skills at lower doses to unconsciousness, anterograde amnesia, and central nervous system depression at higher doses. Cell membranes are highly permeable to alcohol, so once alcohol is in the bloodstream it can diffuse into nearly every cell in the body.

The concentration of alcohol in blood is measured via blood alcohol content (BAC). The amount and circumstances of consumption play a large part in determining the extent of intoxication; for example, eating a heavy meal before alcohol consumption causes alcohol to absorb more slowly.[12] Hydration also plays a role, especially in determining the extent of hangovers. After binge drinking, unconsciousness can occur and extreme levels of consumption can lead to alcohol poisoning and death (a concentration in the blood stream of 0.40% will kill half of those affected[13][medical citation needed]). Alcohol may also cause death indirectly, by asphyxiation from vomit.

Alcohol disrupts normal sleep patterns thereby reducing sleep quality and can greatly exacerbate sleep problems. During abstinence, residual disruptions in sleep regularity and sleep patterns are the greatest predictors of relapse.[14]

Long-term effects[edit | edit source]

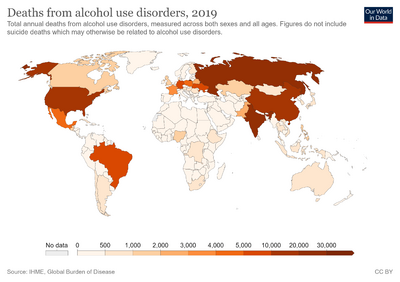

According to the World Health Organization's 2018 Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, there are more than 3 million people who die from the harmful effects of alcohol each year, which amounts to more than 5% of the burden of disease worldwide.[15] The US National Institutes of Health similarly estimates that 3.3 million deaths (5.9% of all deaths) were believed to be due to alcohol each year.[16]

Guidelines in the US and the UK advise that if people choose to drink, they should drink moderately.[17][18]

Even light and moderate alcohol consumption increases a person's cancer risk, especially the risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, cancers of the mouth and tongue, liver cancer, and breast cancer.[6][7]

A systematic analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study, which was an observational study, found that long-term consumption of any amount of alcohol is associated with an increased risk of death in all people, and that even moderate consumption appears to be risky.[19] Similar to prior analyses, it found an apparent benefit for older women in reducing the risks of death from ischemic heart disease and from diabetes mellitus, but unlike prior studies it found those risks cancelled by an apparent increased risk of death from breast cancer and other causes.[19] A 2016 systematic review and meta-analysis found that moderate ethanol consumption brought no mortality benefit compared with lifetime abstention from ethanol consumption.[20] Risk is greater in younger people due to heavy episodic drinking which may result in violence or accidents.[21]

Long-term heavy use of alcohol damages nearly every organ and system in the body.[22] Risks include alcohol use disorder, malnutrition, chronic pancreatitis, alcoholic liver disease (e.g., permanent liver scarring) and several types of cancer. In addition, damage to the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system (e.g., painful peripheral neuropathy) can occur from chronic alcohol misuse.[23][24]

The developing adolescent brain is particularly vulnerable to the toxic effects of alcohol.[25]

DNA damage[edit | edit source]

Acetaldehyde is produced when cells process ethanol. Acetaldehyde, is a DNA damaging metabolite that can interact with DNA to crosslink the two strands of the DNA duplex.[26] The mechanisms the cells use for repairing these crosslinks are error prone,[26] thus leading to mutations that in the long term can cause cancer.

Pregnancy[edit | edit source]

Medical organizations strongly discourage drinking alcohol during pregnancy.[27][28][29] Alcohol passes easily from the mother's bloodstream through the placenta and into the bloodstream of the fetus,[30] which interferes with brain and organ development.[31] Alcohol can affect the fetus at any stage during pregnancy, but the level of risk depends on the amount and frequency of alcohol consumed.[31] Regular heavy drinking and heavy episodic drinking (also called binge drinking), entailing four or more standard alcoholic drinks (a pint of beer or 50 ml drink of a spirit such as whisky corresponds to about two units of alcohol) on any one occasion, pose the greatest risk for harm, but lesser amounts can cause problems as well.[31] There is no known safe amount or safe time to drink during pregnancy, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends complete abstinence for women who are pregnant, trying to become pregnant, or are sexually active and not using birth control.[32][33]

Prenatal alcohol exposure can lead to fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs). The most severe form of FASD is fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS).[32] Problems associated with FASD include abnormal facial development, low birth weight, stunted growth, small head size, delayed or uncoordinated motor skills, hearing or vision problems, learning disabilities, behavior problems, and inappropriate social skills compared to same-age peers.[34][35] Those affected are more likely to have trouble in school, legal problems, participate in high-risk behaviors, and develop substance use disorders like excessive drinking themselves.[34]

Cardiovascular disease[edit | edit source]

In 2010, a systematic review reported that moderate consumption of alcohol does not cause harm to people with cardiovascular disease. However, the authors did not encourage people to start drinking alcohol in the hope of any benefit.[36] In a 2018 study on 599,912 drinkers, a roughly linear association was found with alcohol consumption and a higher risk of stroke, coronary artery disease excluding myocardial infarction, heart failure, fatal hypertensive disease, and fatal aortic aneurysm, even for moderate drinkers.[37][non-primary source needed] The American Heart Association states that people who are currently non-drinkers should not start drinking alcohol.[38] Alcohol consumption also increases the risk of developing harmful abnormal heart rhythms such as atrial fibrillation, even with regular light to moderate alcohol use.[39]

Breastfeeding[edit | edit source]

The UK National Health Service states that "an occasional drink is unlikely to harm" a breastfed baby, and recommends consumption of "no more than one or two units of alcohol once or twice a week" for breastfeeding mothers (where a pint of beer or 50 ml drink of a spirit such as whisky corresponds to about two units of alcohol).[40] The NHS also recommends to wait for a couple of hours before breastfeeding or express the milk into a bottle before drinking.[40] Researchers have shown that intoxicated breastfeeding reduces the average milk expression but poses no immediate threat to the child as the amount of transferred alcohol is insignificant.[41]

Alcohol education[edit | edit source]

Alcohol education is the practice of disseminating information about the effects of alcohol on health, as well as society and the family unit.[42] It was introduced into the public schools by temperance organizations such as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union in the late 19th century.[42] Initially, alcohol education focused on how the consumption of alcoholic beverages affected society, as well as the family unit.[42] In the 1930s, this came to also incorporate education pertaining to alcohol's effects on health.[42] Organizations such as the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in the United States were founded to promulgate alcohol education alongside those of the temperance movement, such as the American Council on Alcohol Problems.[42][43]

Alcohol expectations[edit | edit source]

Alcohol expectations are beliefs and attitudes that people have about the effects they will experience when drinking alcoholic beverages. They are just largely beliefs about alcohol's effects on a person's behaviors, abilities, and emotions. Some people believe that if alcohol expectations can be changed, then alcohol use disorders might be reduced. Men tend to become more aggressive in laboratory studies in which they are drinking only tonic water but believe that it contains alcohol. They also become less aggressive when they believe they are drinking only tonic water, but are actually drinking tonic water that contains alcohol.[44]

The phenomenon of alcohol expectations recognizes that intoxication has real physiological consequences that alter a drinker's perception of space and time, reduce psychomotor skills, and disrupt equilibrium.[45] The manner and degree to which alcohol expectations interact with the physiological short-term effects of alcohol, resulting in specific behaviors, is unclear.

A single study found that if a society believes that intoxication leads to sexual behavior, rowdy behavior, or aggression, then people tend to act that way when intoxicated. But if a society believes that intoxication leads to relaxation and tranquil behavior, then it usually leads to those outcomes. Alcohol expectations vary within a society, so these outcomes are not certain.[46]

People tend to conform to social expectations, and some societies expect that drinking alcohol will cause disinhibition. However, in societies in which the people do not expect that alcohol will disinhibit, intoxication seldom leads to disinhibition and bad behavior.[45]

Alcohol expectations can operate in the absence of actual consumption of alcohol. Research in the United States over a period of decades has shown that men tend to become more sexually aroused when they think they have been drinking alcohol—even when they have not been drinking it.

Drug treatment programs[edit | edit source]

Most addiction treatment programs encourage people with drinking problems to see themselves as having a chronic, relapsing disease that requires a lifetime of attendance at 12-step meetings to keep in check.

Alcohol use disorder[edit | edit source]

Alcohol misuse prevention programs[edit | edit source]

More than 200 injuries and disease conditions are caused due to alcohol misuse.[48] It is a causative agent influencing maternal health and development, noncommunicable diseases (including cancer and cardiovascular diseases), injuries, violence, mental health, and infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS.[49] Harmful use of alcohol has been identified as a global health issue, and its management is a priority in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.[50] In 2018, WHO launched the initiative SAFER, to decrease the number of deaths, diseases and injuries caused by alcohol misuse. It has been developed to address the regional, country and global health and developmental goals using high-impact, cost-effective, evidence-based interventions. Using a set of WHO tools and resources SAFER will concentrate on the more cost-effective interventions to reduce and prevent alcohol misuse.[51] The five WHO "best buys" for decreasing alcohol misuse are priority in this action plan:[48]

- Strengthen restrictions on alcohol availability.

- Advance and enforce drink driving countermeasures.

- Facilitate access to screening, brief interventions, and treatment.

- Enforce bans or comprehensive restrictions on alcohol advertising, sponsorship, and promotion.

- Raise prices on alcohol through excise taxes and pricing policies.

The promotion and success of the SAFER initiative is based on three key principles to implement, to monitor, and to protect.[48]

Recommended maximum intake[edit | edit source]

Binge drinking is becoming a major problem in the UK. Advice on weekly consumption is avoided in United Kingdom.[52]

Since 1995, the UK government has advised that regular consumption of three to four units (one unit equates to 10 mL of pure ethanol) a day for men and or two to three units for women, would not pose significant health risks. However, consistently drinking more than four units a day (for men) and three units (women) is not advisable.[53]

Previously (from 1992 until 1995), the advice was that men should drink no more than 21 units per week, and women no more than 14.[54] (The difference between the sexes was due to the typically lower weight and water-to-body-mass ratio of women.) This was changed because a government study showed that many people were in effect "saving up" their units and using them at the end of the week, a phenomenon referred to as binge drinking.[55] The Times reported in October 2007 that these limits had been "plucked out of the air" and had no scientific basis.[56]

Sobriety[edit | edit source]

Sobriety is the condition of not having any measurable levels, or effects from mood-altering drugs. According to WHO "Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms", sobriety is continued abstinence from psychoactive drug use.[57]

Sobriety is also considered to be the natural state of a human being given at a birth. In a treatment setting, sobriety is the achieved goal of independence from consuming or craving mind-altering substances. As such, sustained abstinence is a prerequisite for sobriety. Early in abstinence, residual effects of mind-altering substances can preclude sobriety. These effects are labeled post-acute-withdrawal syndrome (PAWS). Someone who abstains, but has a latent desire to resume use, is not considered truly sober. An abstainer may be subconsciously motivated to resume drug use, but for a variety of reasons, abstains (e.g. such as a medical or legal concern precluding use).[58]

Sobriety has more specific meanings within specific contexts, such as the culture of Alcoholics Anonymous, other 12 step programs, law enforcement, and some schools of psychology. In some cases, sobriety implies achieving "life balance".[59]

Injury and deaths[edit | edit source]

Injury is defined as physical damage or harm that is done or sustained. The potential of injuring oneself or others can be increased after consuming alcohol due to the certain short term effects related to the substance such as lack of coordination, blurred vision, and slower reflexes to name a few.[60] Due to these effects the most common injuries include head, fall, and vehicle-related injuries. A study was conducted of patients admitted to the Ulster Hospital in Northern Ireland with fall related injuries. They found that 113 of those patients admitted to that hospital during that had consumed alcohol recently and that the injury severity was higher for those that had consumed alcohol compared to those that had not.[61] Another study showed that 21% of patients admitted to the Emergency Department of the Bristol Royal Infirmary had either direct or indirect alcohol related injuries. If these figures are extrapolated it shows that the estimated number of patients with alcohol related injuries are over 7,000 during the year at this emergency department alone.[62]

In the United States alcohol resulted in about 88,000 deaths in 2010.[63] The World Health Organization calculated that more than 3 million people, mostly men, died as a result of harmful use of alcohol in 2016. This was about 13.5% of the total deaths of people between 20 and 39. More than 5% of the global disease burden was caused by the harmful use of alcohol.[64] There are even higher estimates for Europe.[65]

Genetic differences[edit | edit source]

Alcohol flush and respiratory reactions[edit | edit source]

Alcohol flush reaction is a condition in which an individual's face or body experiences flushes (appears red) or blotches as a result of an accumulation of acetaldehyde, a metabolic byproduct of the catabolic metabolism of alcohol. It is best known as a condition that is experienced by people of Asian descent. According to the analysis by HapMap Project, the rs671 allele of the ALDH2 gene responsible for the flush reaction is rare among Europeans and Africans, and it is very rare among Mexican-Americans. 30% to 50% of people of Chinese and Japanese ancestry have at least one ALDH*2 allele.[66] The rs671 form of ALDH2, which accounts for most incidents of alcohol flush reaction worldwide, is native to East Asia and most common in southeastern China. It most likely originated among Han Chinese in central China,[67] and it appears to have been positively selected in the past. Another analysis correlates the rise and spread of rice cultivation in Southern China with the spread of the allele.[68] The reasons for this positive selection are unknown, but the hypothesis that elevated concentrations of acetaldehyde may have conferred protection against certain parasitic infections, such as Entamoeba histolytica have been suggested.[69] The same SNP allele of ALDH2, also termed glu487lys, and the abnormal accumulation of acetaldehyde following the drinking of alcohol, is associated with the alcohol-induced respiratory reactions of rhinitis and asthma that occur in Eastern Asian populations.[70]

and then to acetic acid (ethanoic acid)

Alcohol and Native Americans[edit | edit source]

Compared with the United States population in general, the Native American population is much more susceptible to alcohol use disorder and related diseases and deaths.[71] From 2006 to 2010, alcohol-attributed deaths accounted for 11.7 percent of all Native American deaths, more than twice the rates of the general U.S. population. The median alcohol-attributed death rate for Native Americans (60.6 per 100,000) was twice as high as the rate for any other racial or ethnic group.[72] Males are affected disproportionately more by alcohol-related conditions than females.[73]

Native American and Native Alaskan youth are far more likely to experiment with alcohol at a younger age than non-Native youth.[74] Low self-esteem and transgenerational trauma have been associated with substance use disorders among Native American teens in the U.S. and Canada.[75][76]

Native American populations exhibit genetic differences in the alcohol-metabolizing enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase and ALDH,[77][78] although evidence that these genetic factors are more prevalent in Native Americans than other ethnic groups has been a subject of debate.[79][80][81] According to one 2013 review of academic literature on the issue, there is a "substantial genetic component in Native Americans" and that "most Native Americans lack protective variants seen in other populations."[79] Many scientists have provided evidence of the genetic component of alcohol use disorder by the biopsychosocial model of alcohol use disorder. Molecular genetics research currently has not found one specific gene that is responsible for the rates of alcohol use disorder among Native Americans, implying the phenomenon may be due to an interplay of multiple genes and environmental factors.[82][83] Research on alcohol use disorder in families suggests that learned behavior augments genetic factors in increasing the probability that children of people with alcohol use disorder will themselves have problems with alcohol misuse.[84]

Genetics and amount of consumption[edit | edit source]

Having a particular genetic variant (A-allele of ADH1B rs1229984) is associated with non-drinking and lower alcohol consumption. This variant is also associated with favorable cardiovascular profile and a reduced risk of coronary artery disease compared to those without the genetic variant, but it is unknown whether this may be caused by differences in alcohol consumption or by additional confounding effects of the genetic variant itself.[85]

Gender differences[edit | edit source]

Historically, according to the British Medical Journal, "men have been far more likely than women to drink alcohol and to drink it in quantities that damage their health, with some figures suggesting up to a 12-fold difference between the sexes."[86] However, analysis of data collected over a century from multiple countries suggests that the gender gap in alcohol consumption is narrowing, and that young women (born after 1981) are consuming alcohol more than their male counterparts. Such findings have implications for the way in which alcohol-use prevention and intervention programs are designed and implemented.[87]

Alcohol use disorder[edit | edit source]

Based on combined data from SAMHSA's 2004-2005 National Surveys on Drug Use & Health, the rate of past year alcohol use disorder among people aged 12 or older varied by level of alcohol use: 44.7% of past month heavy drinkers, 18.5% binge drinkers, 3.8% past month non-binge drinkers, and 1.3% of those who did not drink alcohol in the past month met the criteria for alcohol dependence or misuse in the past year. Males had higher rates than females for all measures of drinking in the past month: any alcohol use (57.5% vs. 45%), binge drinking (30.8% vs. 15.1%), and heavy alcohol use (10.5% vs. 3.3%), and males were twice as likely as females to have met the criteria for alcohol dependence or misuse in the past year (10.5% vs. 5.1%).[88][needs update] Over time the difference between males and females has narrowed. According to a 2016 systematic review, for those born at the end of the 20th century, men were 1.2 times as likely to drink to problematic levels and 1.3 times as likely to develop health problems from drinking.[87]

Sensitivity[edit | edit source]

Several biological factors make women more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol than men.[89]

- Body fat. Women tend to weigh less than men, and—pound for pound—a woman's body contains less water and more fatty tissue than a man's. Because fat retains alcohol while water dilutes it, alcohol remains at higher concentrations for longer periods of time in a woman's body, exposing her brain and other organs to more alcohol.

- Enzymes. Women have lower levels of two enzymes—alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase—that metabolize (break down) alcohol in the stomach and liver. As a result, women absorb more alcohol into their bloodstreams than men.

- Hormones. Changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle may also affect how a woman metabolizes alcohol.

Metabolism[edit | edit source]

Females demonstrated a higher average rate of elimination (mean, 0.017; range, 0.014–0.021 g/210 L) than males (mean, 0.015; range, 0.013–0.017 g/210 L). Female subjects on average had a higher percentage of body fat (mean, 26.0; range, 16.7–36.8%) than males (mean, 18.0; range, 10.2–25.3%).[90]

Depression[edit | edit source]

The link between alcohol consumption, depression, and gender was examined by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Canada). The study found that women taking antidepressants consumed more alcohol than women who did not experience depression as well as men taking antidepressants. The researchers, Dr. Kathryn Graham and a PhD Student, Agnes Massak, analyzed the responses to a survey by 14,063 Canadian residents aged 18–76 years. The survey included measures of quantity, frequency of drinking, depression, and antidepressant use, over the period of a year. The researchers used data from the GENACIS Canada survey, part of an international collaboration to investigate the influence of cultural variation on gender differences in alcohol use and related problems. The purpose of the study was to examine whether, like in other studies already conducted on male depression and alcohol consumption, depressed women also consumed less alcohol when taking anti-depressants. According to the study, both men and women experiencing depression (but not on antidepressants) drank more than non-depressed counterparts. Men taking antidepressants consumed significantly less alcohol than depressed men who did not use antidepressants. Non-depressed men consumed 436 drinks per year, compared to 579 drinks for depressed men not using antidepressants, and 414 drinks for depressed men who used antidepressants. Alcohol consumption remained higher whether the depressed women were taking antidepressants or not. 179 drinks per year for non-depressed women, 235 drinks for depressed women not using antidepressants, and 264 drinks for depressed women who used antidepressants. The lead researcher argued that the study "suggests that the use of antidepressants is associated with lower alcohol consumption among men with depression. But this does not appear to be true for women."[91]

See also[edit | edit source]

- Alcoholic beverage

- Short-term effects of alcohol consumption

- Long-term effects of alcohol consumption

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "Alcohol and diabetes: Drinking safely – Mayo Clinic". Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Risks of Adolescent Alcohol Use". HHS.gov. 19 January 2018. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ↑ "There is no safe level of alcohol, new study confirms". www.euro.who.int. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ↑ "No alcohol safe to drink, global study confirms". BBC News. 24 August 2018. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ↑ Stories, Daily Health (20 November 2018). "Study: No Level of Alcohol is Safe". Cleveland Clinic Newsroom. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cheryl Platzman Weinstock (8 November 2017). "Alcohol Consumption Increases Risk of Breast and Other Cancers, Doctors Say". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

The ASCO statement, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, cautions that while the greatest risks are seen with heavy long-term use, even low alcohol consumption (defined as less than one drink per day) or moderate consumption (up to two drinks per day for men, and one drink per day for women because they absorb and metabolize it differently) can increase cancer risk. Among women, light drinkers have a four percent increased risk of[breast cancer, while moderate drinkers have a 23 percent increased risk of the disease.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Noelle K. LoConte, Abenaa M. Brewster, Judith S. Kaur, Janette K. Merrill, and Anthony J. Alberg (7 November 2017). "Alcohol and Cancer: A Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 36 (1).

Clearly, the greatest cancer risks are concentrated in the heavy and moderate drinker categories. Nevertheless, some cancer risk persists even at low levels of consumption. A meta-analysis that focused solely on cancer risks associated with drinking one drink or fewer per day observed that this level of alcohol consumption was still associated with some elevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (sRR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.56), oropharyngeal cancer (sRR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.29), and breast cancer (sRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.08), but no discernable associations were seen for cancers of the colorectum, larynx, and liver.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Global status report on alcohol and health" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2014. pp. vii. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ↑ Griswold, MG; Fullman, N; Hawley, C; Arian, N; Zimsen, SM; et al. (August 2018). "Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". The Lancet. 392 (10152): 1015–1035. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. PMC 6148333. PMID 30146330.

- ↑ "Cancer warning labels to be included on alcohol in Ireland, minister confirms". Belfasttelegraph.co.uk. Belfast Telegraph. 26 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Meyer, Jerold S. and Linda F. Quenzer. Psychopharmacology: Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior. Sinauer Associates, Inc.: Sunderland, Massachusetts. 2005. Page 228.

- ↑ Horowitz M, Maddox A, Bochner M, et al. (1989). "Relationships between gastric emptying of solid and caloric liquid meals and alcohol absorption". Am. J. Physiol. 257 (2 Pt 1): G291–6298. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.1989.257.2.G291. PMID 2764113.

- ↑ "Carleton College: Wellness Center: Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC)". Archived from the original on 14 September 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ↑ Feige B, Scaal S, Hornyak M, Gann H, Riemann D (2007). "Sleep electroencephalographic spectral power after withdrawal from alcohol in alcohol-dependent patients". Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 31 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00260.x. PMID 17207097.

- ↑ "WHO | Global status report on alcohol and health 2018". Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ "Alcohol Facts and Statistics". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ "Appendix 9. Alcohol - 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines - health.gov". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ "New alcohol advice issued". NHS. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators (August 2018). "Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". Lancet. 392 (10152): 1015–1035. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. PMC 6148333. PMID 30146330.

- ↑ Stockwell T, Zhao J, Panwar S, Roemer A, Naimi T, Chikritzhs T (2016). "Do "Moderate" Drinkers Have Reduced Mortality Risk? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Alcohol Consumption and All-Cause Mortality". J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 77 (2): 185–198. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.185. PMC 4803651. PMID 26997174.

- ↑ O'Keefe, JH; Bhatti, SK; Bajwa, A; DiNicolantonio, JJ; Lavie, CJ (2014). "Alcohol and cardiovascular health: the dose makes the poison...or the remedy". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 89 (3): 382–393. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.11.005. PMID 24582196.

- ↑ Caan, Woody; Belleroche, Jackie de, eds. (11 April 2002). Drink, Drugs and Dependence: From Science to Clinical Practice (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-415-27891-1.

- ↑ Müller D, Koch RD, von Specht H, Völker W, Münch EM (March 1985). "Neurophysiologic findings in chronic alcohol abuse". Psychiatr Neurol Med Psychol (Leipz) (in Deutsch). 37 (3): 129–32. PMID 2988001.

- ↑ Testino G (2008). "Alcoholic diseases in hepato-gastroenterology: a point of view". Hepatogastroenterology. 55 (82–83): 371–377. PMID 18613369.

- ↑ Guerri, C.; Pascual, M.A. (2010). "Mechanisms involved in the neurotoxic, cognitive, and neurobehavioral effects of alcohol consumption during adolescence". Alcohol. 44 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.003. PMID 20113871.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hodskinson MR, Bolner A, Sato K, Kamimae-Lanning AN, Rooijers K, Witte M, Mahesh M, Silhan J, Petek M, Williams DM, Kind J, Chin JW, Patel KJ, Knipscheer P. Alcohol-derived DNA crosslinks are repaired by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2020 Mar;579(7800):603-608. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2059-5. Epub 2020 Mar 4. PMID 32132710; PMCID: PMC7116288

- ↑ Vice Admiral Richard H. Carmona (2005). "A 2005 Message to Women from the U.S. Surgeon General" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Committee to Study Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, Division of Biobehavioral Sciences and Mental Disorders, Institute of Medicine (1995). Fetal alcohol syndrome : diagnosis, epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. doi:10.17226/4991. ISBN 978-0-309-05292-4. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ "Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council". Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ↑ Nathanson, Vivienne; Nicky Jayesinghe; George Roycroft (27 October 2007). "Is it all right for women to drink small amounts of alcohol in pregnancy? No". BMJ. 335 (7625): 857. doi:10.1136/bmj.39356.489340.AD. PMC 2043444. PMID 17962287.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 "Fetal Alcohol Exposure". April 2015. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Facts about FASDs". 16 April 2015. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "More than 3 million US women at risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancy". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 February 2016. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

'drinking any alcohol at any stage of pregnancy can cause a range of disabilities for their child,' said Coleen Boyle, Ph.D., director of CDC's National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Coriale; et al. (2013). "Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD): neurobehavioral profile, indications for diagnosis and treatment". Rivista di Psichiatria. 48 (5): 359–69. doi:10.1708/1356.15062. PMID 24326748.

- ↑ Chudley; et al. (2005), "Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis", CMAJ, 172 (5 Suppl): S1–S21, doi:10.1503/cmaj.1040302, PMC 557121, PMID 15738468

- ↑ Costanzo S, Di Castelnuovo A, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G (2010). "Alcohol consumption and mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55 (13): 1339–1347. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.006. PMID 20338495.

- ↑ Wood AM, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS, Willeit P, Warnakula S, Bolton T, et al. (2018). "Risk thresholds for alcohol consumption: combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599 912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies". The Lancet. 391 (10129): 1513–1523. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30134-X. PMC 5899998. PMID 29676281.

- ↑ "Alcohol and Heart Health". American Heart Association. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ "One Drink a Day Raises Risk of Atrial Fibrillation". Healthline. 15 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Choices, N. H. S. (1 May 2017). "Breastfeeding and drinking alcohol – Pregnancy and baby guide – NHS Choices". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Haastrup, MB; Pottegård, A; Damkier, P (2014). "Alcohol and Breastfeeding". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 114 (2): 168–173. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12149. PMID 24118767. S2CID 31580580.

even in a theoretical case of binge drinking, the children would not be subjected to clinically relevant amounts of alcohol

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 Moore, Mark Harrison; Gerstein, Dean R. (1981). Alcohol and Public Policy. National Academies. p. 90–93.

- ↑ Martin, Scott C. (2014). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol: Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781483374383.

- ↑ Grattan, Karen E.; Vogel-Sprott, M. (2001). "Maintaining Intentional Control of Behavior Under Alcohol". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 25 (2): 192–7. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02198.x. PMID 11236832.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 MacAndrew, C. and Edgerton. Drunken Comportment: A Social Explanation. Chicago: Aldine, 1969.

- ↑ Marlatt GA, Rosenow (1981). "The think-drink effect". Psychology Today. 15: 60–93.

- ↑ Nutt, D; King, LA; Saulsbury, W; Blakemore, C (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–53. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 "WHO | THE SAFER INITIATIVE". WHO. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ World Health Organization. (14 February 2019). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization,, World Health Organization. Management of Substance Abuse Team. Geneva. ISBN 978-92-4-156563-9. OCLC 1089229677.

- ↑ Nations, United (31 December 2015). "Transforming governance for the 2030 agenda for sustainable development": 73–87. doi:10.18356/e5a72957-en. Archived from the original on 3 June 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases : 2013-2020. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland. ISBN 978-92-4-150623-6. OCLC 960910741.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "Sensible Drinking". Aim-digest.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Alcohol misuse : Department of Health". Dh.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ "Alcohol and health: how alcohol can affect your long and short term health". Drinkaware.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ Mohsin Beg (31 August 2021). "Medical Detox Center". Retreatofatlanta.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ↑ Drink limits 'useless’ Archived 1 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Times, 20 October 2007

- ↑ "Lexicon and drug terms". Who.int. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on 4 July 2004. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ MD Basharin K.G. (2010). "Scientific grounding for sobriety: Western experience" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions (PDF). Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. April 1953. ISBN 978-0-916856-01-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2018. (Electronic .PDF version, September 2005).

- ↑ "Drinkwise Australia". DrinkWise Australia. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Johnson J, McGovern S (2003). "Alcohol related falls: an interesting pattern of injuries". Emergency Medicine Journal. 21 (2): 185–188. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.006130. PMC 1726307. PMID 14988344.

- ↑ Hoskins R, Benger J (2013). "What is the burden of alcohol-related injuries in an inner city emergency department?". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 33 (9): 1532–1538. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00981.x. PMC 2757258. PMID 19485974.

- ↑ "Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost — 11 states, 2006–2010". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ "Alcohol". World health Organization. 21 September 2018. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ↑ Korotayev, A., Khaltourina, D., Meshcherina, K., & Zamiatnina, E. Distilled Spirits Overconsumption as the Most Important Factor of Excessive Adult Male Mortality in Europe. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 2018, 53(6), 742-752 Archived 8 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Rs671". SNPmedia. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Hui Li; et al. (2009). "Refined Geographic Distribution of the Oriental ALDH2*504Lys (nee 487Lys) Variant". Ann Hum Genet. 73 (Pt 3): 335–345. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00517.x. PMC 2846302. PMID 19456322.

- ↑ Yi Peng; Hong Shi; Xue-bin Qi; Chun-jie Xiao; Hua Zhong; Run-lin Z Ma; Bing Su (2010). "The ADH1B Arg47His polymorphism in East Asian populations and expansion of rice domestication in history". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1): 15. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-15. PMC 2823730. PMID 20089146.

- ↑ Oota H, Pakstis AJ, Bonne-Tamir B, Goldman D, Grigorenko E, Kajuna SL, et al. (2004). "The evolution and population genetics of the ALDH2 locus: random genetic drift, selection, and low levels of recombination". Ann. Hum. Genet. 68 (Pt 2): 93–109. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00060.x. PMID 15008789. S2CID 31026948.

- ↑ Adams, KE; Rans, TS (2013). "Adverse reactions to alcohol and alcoholic beverages". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 111 (6): 439–445. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.09.016. PMID 24267355.

- ↑ "Philip A. May, "Overview of Alcohol Abuse Epidemiology for American Indian Populations," in Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health, Gary D. Sandefur, Ronald R. Rindfuss, Barney Cohen, Editors. Committee on Population, Commission on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education National Research Council. National Academy Press: Washington, D.C. 1996" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Gonzales, K; Roeber, J; Kanny, D; Tran, A; Saiki, C; Johnson, H; Yeoman, K; Safranek, T; Creppage, K; Lepp, A; Miller, T; Tarkhashvili, N; Lynch, KE; Watson, JR; Henderson, D; Christenson, M; Geiger, SD (2014). "Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost--11 States, 2006-2010". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 63 (10): 213–6. PMC 5779340. PMID 24622285.

- ↑ Whitesell, NR; Beals, J; Crow, CB; Mitchell, CM; Novins, DK (2012). "Epidemiology and etiology of substance use among American Indians and Alaska Natives: risk, protection, and implications for prevention". Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 38 (5): 376–82. doi:10.3109/00952990.2012.694527. PMC 4436971. PMID 22931069.

- ↑ Beauvais F (1998). "Cultural identification and substance use in North America--an annotated bibliography". Subst Use Misuse. 33 (6): 1315–36. doi:10.3109/10826089809062219. PMID 9603273.

- ↑ Myhra LL (2011). ""It runs in the family": intergenerational transmission of historical trauma among urban American Indians and Alaska Natives in culturally specific sobriety maintenance programs". Am Indian Alsk Native Ment Health Res. 18 (2): 17–40. doi:10.5820/aian.1802.2011.17. PMID 22302280.

- ↑ Bombay, Amy; Matheson, Kim; Anisman, Hymie (2009). "Intergenerational trauma: convergence of multiple processes among First Nations peoples in Canada". Journal of Aboriginal Health. 5 (3): 6–47. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ↑ Ehlers, CL (2007). "Variations in ADH and ALDH in Southwest California Indians". Alcohol Res Health. 30 (1): 14–7. PMC 3860438. PMID 17718395.

- ↑ Ehlers, CL; Liang, T; Gizer, IR (2012). "ADH and ALDH polymorphisms and alcohol dependence in Mexican and Native Americans". Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 38 (5): 389–94. doi:10.3109/00952990.2012.694526. PMC 3498484. PMID 22931071.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "Ehlers CL, Gizer IR. "Evidence for a genetic component for substance dependence in Native Americans." Am J Psychiatry. 1 Feb 2013;170(2):154–164". Archived from the original on 21 January 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Caetano, Raul; Clark, Catherine L.; Tam, Tammy (1998). "Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities". Alcohol Health and Research World. 22 (4): 233–241. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.556.6875.

- ↑ "Karen Chartier and Raul Caetano, "Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research," Alcohol Res Health 2010, vol. 33: 1-2 pp. 152-160". Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Wall, Tamara L.; Carr, Lucinda G.; Ehlers, Cindy L. (2003). "Protective association of genetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase with alcohol dependence in Native American Mission Indians". American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.41. PMID 12505800.

- ↑ Wilhelmsen, KC; Ehlers, C (2005). "Heritability of substance dependence in a native American population". Psychiatr Genet. 15 (2): 101–7. doi:10.1097/00041444-200506000-00006. PMID 15900224. S2CID 5859834.

- ↑ Brockie, TN; Heinzelmann, M; Gill, J (2013). "A Framework to Examine the Role of Epigenetics in Health Disparities among Native Americans". Nurs Res Pract. 2013: 410395. doi:10.1155/2013/410395. PMC 3872279. PMID 24386563.

- ↑ Holmes, Michael V.; et al. (2014). "Association between alcohol and cardiovascular disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data". BMJ. 349: g4164. doi:10.1136/bmj.g4164. PMC 4091648. PMID 25011450.

- ↑ "Women catching up with men in alcohol consumption and its associated harms" (PDF). BMJ Open (Press release). 25 October 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Slade T, Chapman C, Swift W, Keyes K, Tonks Z, Teesson M (2016). "Birth cohort trends in the global epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol-related harms in men and women: systematic review and metaregression". BMJ Open. 6 (10): e011827. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011827. PMC 5093369. PMID 27797998.

- ↑ "Gender differences in alcohol use and alcohol dependence or abuse: 2004 or 2005." The NSDUH Report. Accessed 22 June 2012.

- ↑ "Women & Alcohol: The Hidden Risks of Drinking". Helpguide.org. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- ↑ Cowan, JM Jr; Weathermon, A; McCutcheon, JR; Oliver, RD (September 1996). "Determination of volume of distribution for ethanol in male and female subjects". J Anal Toxicol. 20 (5): 287–90. doi:10.1093/jat/20.5.287. PMID 8872236.

- ↑ Graham, K.; Massak, A. (2007). "Alcohol consumption and the use of antidepressants". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 176 (5): 633–637. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060446. PMC 1800314. PMID 17325328.

External links[edit | edit source]

Categories: [Alcohol and health] [Articles containing video clips]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 06/17/2024 10:23:42 | 13 views

☰ Source: https://mdwiki.org/wiki/Alcohol_and_health | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

![{\displaystyle {\ce {H}}{-}{\overset {\displaystyle {\ce {H}} \atop |}{\underset {| \atop \displaystyle {\ce {H}}}{\ce {C}}}}{-}{\overset {\displaystyle {\ce {H}} \atop |}{\underset {| \atop \displaystyle {\ce {H}}}{\ce {C}}}}{\ce {-O-H->[{\ce {ADH}}]H}}{-}{\overset {\displaystyle {\ce {H}} \atop |}{\underset {| \atop \displaystyle {\ce {H}}}{\ce {C}}}}{-}{\overset {\displaystyle {\ce {H}} \atop |}{\underset {\| \atop \displaystyle {\ce {O}}}{\ce {C}}}}{\ce {->[{\ce {ALDH}}]H}}{-}{\overset {\displaystyle {\ce {H}} \atop |}{\underset {| \atop \displaystyle {\ce {H}}}{\ce {C}}}}{-}{\overset {\color {white}{\displaystyle {\ce {H}} \atop |}}{\underset {\| \atop \displaystyle {\ce {O}}}{\ce {C}}}}{\ce {-O-H}}}](tmp/0Hs5Do8jaTXg/data/media/images/8e29ab9d559420e2df0bf9ff99bef27374c71271.svg)

KSF

KSF