Samuel Adams

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | Founding Fathers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Samuel Adams | |

| State | Massachusetts |

| Religion | Christian- Congregationalist [1] |

| Founding Documents | Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation |

Samuel Adams (1722-1803) was a fearless activist who signed the Declaration of Independence and inspired others with his personal participation in anti-British events. An enthusiastic Christian, Samuel Adams was the fourth governor of Massachusetts (preceded by John Hancock), and the second cousin of John Adams who was the second President of the United States. In contrast with his famous cousin, Samuel Adams was known for his great animosity toward England's presence in the colonial affairs.[2]

Adams was a strong and vocal opponent of many of the British Parliamentary acts designed to raise revenues in the American Colonies. He is thought to have been a leading organizer and participant in the Boston Tea Party, which was done by thinly-disguised protesters.

Contents

Background[edit]

At the age of 14, Adams attended Harvard College, where he received a Masters of Arts degree in 1743. After graduating, Adams started a business which failed and then entered politics full-time, and won a place in the Massachusetts legislature.

In protest of the 1765 passing of the Stamp Act, Adams led in the founding and organizing of the Sons of Liberty.[3] In 1772, Adams wrote the noted The Rights of the Colonists, a resolution of a Boston Committee of Correspondence.

In 1773, Adams and Boston citizens were so outraged with England's Tea Act, which granted the East Indian Company a monopoly on the sale of tea to the American Colonies, that they dumped the British cargo boats into Boston Harbor. This early revolutionary action is referred to as the Boston Tea Party.

In response to the Boston Tea Party, Britain passed laws that closed the Boston Harbor and restricted town meetings, the act was referred to as the "Intolerable Acts". Adams urged a boycott of the British Trade by the American Colonies.

As a member of the Massachusetts legislature, Adams and four others were elected to serve in the First Continental Congress (1774). He again served in the Second Continental Congress where he pushed for full independence from English rule. Adams served in the Continental Congress until 1781, when he returned to Boston to become a State Senator. He served for a time as President of the Massachusetts Senate.[4] In 1788, Adams was a candidate for the U.S. House, but lost the election to Fisher Ames.[5] In 1789, he became the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts.[6] In 1793, at the passing of John Hancock he was elected as Governor of Massachusetts and served until 1797. Adams is the oldest governor the state of Massachusetts has ever had.[7]

Early life[edit]

Samuel Adams was born in Boston, Massachusetts, from an ancient and respectable parentage of the first settlers of New England, on the twenty-seventh day of September, 1722. The record of his early days is lost. Having passed through the primary branches at Master Lovell's school, he entered as a student at Harvard College, in the autumn of the year 1736. The time there allowed to lay the foundation of a future usefulness, was not lost to him or to his country. In accordance with the wishes of his parents, he decided to prepare himself for the duties of the Christian ministry, and to that end he directed his energies. He obtained the honors of his alma mater, not because he had been under her guardianship the usual term, but for his assiduous attention to literary acquirements, that rendered him worthy of them. On receiving his second degree, in conformity with the usages of the college, which retained many forms of the English Universities, he proposed as his thesis, and defended the affirmative of the question, "Whether it be lawful to resist the supreme magistrate, if the commonwealth cannot otherwise be preserved". Thus early had his mind taken its bent, and formed that system of political opinions to which he uniformly and zealously adhered throughout life, and which he never for a moment hesitated to reduce to practice. Nor was this the only instance of his youthful devotion to the welfare of his fellow-men;—out of the stipulated sum allowed him by his father while in college, he saved a sufficiency to publish his masterly defence of "Englishmen's Rights."

Christian beliefs[edit]

Zealous in the support of religion—the church government and discipline of the early Independents of New England, and warmly attached to the doctrines they inculcated, be was led to a veneration of the champions of his peculiar creed, and predisposed to the adoption of their political as well as religious opinions. The quaint writings of Colman, of the elder John Adams, and of the younger Mather, charmed his senses. Of the latter, "upon whose childhood was heaped a mountain of learning and theology," and who went about "smelling out the odoriferous flowers of fancy, those jerks of the imagination"—he expressed the highest admiration.

In such an atmosphere, surrounded by such examples, he pursued with an affectionate ardor the study of theology, and only resigned that profession to enter into the service of Freedom. Thus he became filled with enthusiastic admiration of the sturdy republicanism, the uncompromising principle, and the severe simplicity of manners which characterized the English Puritans of the reigns of James and Charles the First. Of these, and of his ancestors who landed at Plymouth, he never spake, but with reverence and respect. Their sufferings awakened a generous sympathy in his breast, and his holy gratitude for the "goodly heritage " they had bequeathed him and his posterity, never abated.

Colonial agitation[edit]

The period at which Mr. Adams began to take an interest in the public affairs, the provincial governments were continually agitated by contests between their governors and other officers, who were appointed by the Crown, and the Assemblies, which were the immediate representatives of the colonists. There could be no question in his mind, as to the side which he should embrace. The situation of his country in the incipient stages of the Revolution, opened a wide and important field for the display of his singular genius and extensive capacity. The claim of Great Britain "to legislate for the colonies in all cases whatever," drew in its train consequences of vast importance. Without such an authority, it would be difficult to maintain the connection of a parent state, with provinces,—with the exercise of it, the colonists were depressed below the grade of British subjects, and reduced to a state of slavery.

There were very few whose minds could comprehend the important distinctions which were then agitated, or whose reasoning could discern the approaching events of that controversy. Mr. Adams, buoyed up by a sense of the justice and righteousness of the colonists' demands, stood forth first in their defence, and heroically won his title—The Father of the Revolution. In 17M, he was elected to prepare the instructions of the town of Boston to their representatives in the General Assembly. The document is now in existence, and contains the first public denial of the right of the British Parliament to tax the colonies, a denial of parliamentary supremacy, and a direct suggestion of the necessity of Union.

Mr. Adams seems to have been peculiarly formed for the eventful period of his life. His mind was singularly powerful in tracing the result of political principles. The firmness of his heart never failed to support his efforts, whenever he was convinced of the rectitude and propriety of the objects he pursued. He pressed his measures with ardor, because they were founded on calculations tending to the glory and independence of his country. His courage derided the bars thrown in the way of his career, while the sagacity of his mind pierced the clouds in which sophistry involved the subject before him. By this he was enabled to explain, in the most convincing manner, the depression of the colonies, unless a firm and noble stand was then made against the King and the Parliament. He met oppositions and threatening? with an intrepid firmness peculiar to himself; and, with an eye of careless indifference, looked upon the dangers that surrounded him, as mere incidents in the progress of great events.

Conflict with British authority[edit]

At the time of the Stamp Act, Mr. Adams became a conspicuous favorite with the people, and a leader in all the popular proceedings of the day. Warmly engaged, both as a declaimer in town meetings, and as a writer in the public prints, his private affairs were neglected, and he became embarrassed with debts. His poverty attracted the attention of the British adherents, and he was approached with presents and bribes: but he could not be won from the cause of Liberty. "Such is the obstinacy and inflexibility of Adams," said a letter to England, "that he never can be conciliated by any office or gift whatever." Such honesty of purpose was looked upon in Great Britain with ludicrous incredulity, probably occasioned by a confusion of ideas at the anomaly of such a disposition, compared with the personal and daily experience in the British Court.

Early career[edit]

Mr. Adams was chosen one of the representatives from Boston to the General Court or Legislature of Massachusetts, in 1765. Here he remained until his election to the Continental Congress, being annually re-elected for nine years, a period which includes an eventful and interesting portion of the history of American liberty, during the whole of which he was remarkable as well for his political and parliamentary talents, as for his zeal in opposition to the claims, the acts, and the menaces of the royal government. While a member of this body, he was continually employed on committees to draft reports, protests, and other public papers, in which employment he evinced great rapidity and correctness of composition.

In 1768, after the death of Charles Townsend, Lord North entered the service of the king. Soon the effects of his administration were felt throughout the American colonies. New acts of taxation were established, and royal collectors sent from England to enforce them. Public feeling seemed unprepared for action, and averse to a rupture. The Massachusetts Assembly, adopting the sentiments of Samuel Adams, approached the king with a humble petition. To him they recounted the story of their wrongs, and besought him to alleviate them. Among themselves, they advocated the policy of union. "Let us all be of one heart and one mind," said Adams. "Let us call on our sister colonies to join with us. Should our righteous opposition to slavery be named rebellion, let us pursue duty with firmness, and leave the event to heaven." The same year Mr. Adams prepared the letter from the Assembly of Massachusetts to their agent in England, and also the celebrated Massachusetts Circular Letter, addressed to the Speakers of the several Houses of Assembly in the other Colonies. The last production is one of the most important of all American State Papers, as the embodiment of historical data, and indicative of the spirit and temper of the times.*

In the deliberative bodies of his native State, where the foundation of the American Revolution was formed, where the principles and systems of government on which the security and happiness of mankind were established, Samuel Adams's manly eloquence was never resisted with success. His opponents were obliged to yield in silence, only hoping for a change by the means of an army more favorable to their views. His rhetoric was a torrent of figurative language— still, an impressive, sedate strain of reasoning, which could never fail to awaken the interested, or to convince the unprejudiced hearer. His pen was no less powerful than his tongue. A mind well stocked with the sentiments of a Sidney, a Locke, and other great and noble men who had contended against monarchical and ecclesiastical tyranny; with an education which had given it the entire possession of all the principal systems, and abuses of the ancient Grecian and Roman republics, as well as of the despotisms of the world, was capable of carrying conviction to the hearts of all who had not been bribed against their own freedom, or who had not suffered themselves to be betrayed by the allurements of avarice and ambition, or by the impression of fear.

One brief specimen of his eloquence at this period, has been preserved by tradition. A town meeting of Boston had been called at the Old South Church, in consequence of some new aggression upon the rights of the people. The different orators of the patriot party had in turn addressed the meeting, loud in complaint and accusation, but guarded and cautious on every point which might look like an approach towards treasonable expressions, or direct exhortations to resistance. Adams placed himself in the pulpit, and sat quietly listening to all their harangues; at length he rose and made a few remarks, which he closed with the following pithy apologue:

"A Grecian philosopher who was lying asleep on the grass, was suddenly roused by the bite of some animal on the palm of his hand. He closed his hand quickly as he awoke, and found that he had caught in it a small field mouse. As he was examining the little animal which had dared to attack him, it bit him unexpectedly a second time: he dropped it, and it escaped. Now, fellow-citizens, what think you was the reflection which this trifling circumstance gave birth to, in the mind of the philosopher. It was this: That there is no animal, however weak and contemptible, which cannot defend its own liberty, if it will or\j fight for it."

Amidst the cares and anxieties incident to his position, Mr. Adams maintained a cheerful demeanor, and the fullest confidence in the ultimate success of his cause. One morning, when the spirits of the patriots were almost broken with despair, he was accosted by Mather Byles, the celebrated tory clergyman of Boston, with the remark, "Come, friend Samuel, let us relinquish republican phantoms, and attend to our fields." "Yes," said Adams, "you attend to the planting of liberty, and I will grub up the taxes. Thus we shall have pleasant places."

Adams again displayed his forcefulness in writing with the statement The Rights of the Colonists, which made waves throughout the New England colonies and beyond.[8]

The increasing popularity of Mr. Adams, in 1773, rendered it every day more desirable to the royal party that he should be detached from the popular cause, and the efforts to gain him to the side of the ministry were renewed. Governor Gage now thought he would try the experiment. For this purpose he sent a confidential and verbal message by a colonel of his army, who waited on Mr. Adams, and stated the object of his visit. He remarked that an adjustment of the dispute which existed between England and her colonies was much desired; that he was authorized to assure him of reward from the government, if he would cease in his opposition, and that it was the advice of Governor Gage to him, not to incur the further displeasure of his majesty, for his conduct thus far had rendered him liable to the penalties for treason.

Mr. Adams listened with apparent interest to this recital. He asked the British colonel if he would deliver his reply as it should be given, and required his word of honor that it would. Then, rising from his chair, in a tone of indignant defiance he replied, "I trust I have long since made my peace with the King of kings. No personal consideration shall induce me to abandon the righteous cause of my country. Tell Governor Gage it is the advice of Samuel Adams to him, no longer to insult the feelings of an exasperated people." Thus, with a full sense of his own perilous situation, marked out as an object of ministerial vengeance, laboring under severe pecuniary embarrassment, but fearless of personal consequences, he steadily pursued the great object of his soul, the liberty of the people.

Continental Congress[edit]

In 1774 Mr. Adams was elected to the General Congress, first suggested by him, which met at Philadelphia, and the same year was chosen Secretary of the State of Massachusetts, which office he discharged by deputy, while attending his duties in Congress.

Exasperated at the refusal of his promises and advances, General Gage issued his celebrated proclamation of June, 1775, in which he offered and promised his majesty's most gracious pardon to all persons who would lay down their arms and return to the duties of peaceable subjects, excepting only from the benefit of such pardon "Samuel Adams and John Hancock, whose offences were of too flagitious a nature to admit of any other consideration than that of condign punishment." Justly deeming this as the token of despair in a deceived and weak administration, Mr. Adams held the measure in the profoundest contempt, and continued his exertions to prepare his country for the last and most solemn resort which he saw near at hand.

His course in reference to the Declaration of Independence is well known. Firm, dignified, never faltering, and with a steady purpose, he labored for its consummation. Joined hand in hand with Chase, Franklin, John Adams, and Jefferson, he gave to the American colonies a place among the nations of the earth, on the broad and deep foundation of independent sovereignty. Of his splendid rhetorical efforts, but one has come down to us. That is included in the present collection.

The Declaration of Independence was expected but by few—new in idea to a great many, and considered by numbers in every State as a rash and daring measure. The American army was then miserably fed, badly armed, wretchedly clothed, and poorly paid. Paper currency, their only resource, was in rapid depreciation, and there appeared to be nothing to depend on but the magnanimity of the people and the justness of their cause.

At this crisis commissioners from England landed, with offerings of peace and reconciliation. They were surrounded by a well-disciplined and powerful army, supported by a numerous fleet, and filled with the anticipations of conquest. The Congress, with a dignity well worthy of an older and more powerful nation, delegated to Dr. Franklin, John Adams, and Edward Rutledge, the authority of a conference with the royal commissioners. They listened to their overtures, while they reasoned on the necessity of a recession from independence, and then gravely replied, in accordance with their instructions: "The United States have become an independent nation; they have no voice but that of a sovereign power, and there can be no discussion of any propositions which do not acknowledge that sovereignty." These instructions were issued on the motion of Samuel Adams.

At this important moment the patriot army was retreating before the English, in every part of the country. Congress was forced to fly from Philadelphia, and find a shelter where they could mature their counsels and direct the course of action. Under these exigencies Mr. Adams appeared calm and undismayed. No clouds of despair spread over his countenance. Noticing the despondence of his fellow-members, he said, "I hope you do not despair of our final success.-' It was answered that the chance was desperate. "If this be our language," said he, "it is so, indeed. If we wear long faces they will become fashionable. The people take their tone from ours, and if we falter, can it be expected that they will march onward? Let us banish such feelings, and show a spirit that will keep alive the confidence of the people. Better tidings will soon arrive. Our cause is just, and we shall never be abandoned by heaven while we show ourselves worthy of its aid and protection." His words were prophetic. Soon after the news arrived of the triumph at Bennington and the glory of Saratoga's field. These gave a brightness to their prospects, and lent confidence to their hopes. It was a favorite remark with Mr. Adams, in the declining years of his life, that this Congress, the Congress of 1777, "was the smallest but truest Congress we ever had."

Later life[edit]

The treaty of peace with England in 1783, acknowledging the sovereignty of the United States, accomplished the wishes of Mr. Adams. He was then in a situation to contemplate his own past conduct with inexpressible satisfaction. His penetrating eye had long discerned, and his patriotic soul had long anticipated the acme of glory to which his nation would arise. Convinced that the connection with the mother country could not be continued upon the plan adopted by the ministry, his exertions had all tended to the separation and independence now so gloriously achieved.

In the year 1794, on the death of Governor Hancock, Mr. Adams was, by a general vote, elected Governor of the commonwealth of Massachusetts. Here he continued until 1797, when the increasing infirmities of more than threescore and ten years led him to seek a voluntary state of retirement.

In the advanced age of his life he delighted in a recapitulation of the scenes of the Revolution. In this, as in other circumstances, he resembled the Earl of Chatham, who, while he was an old man, became impatient of all subjects which did not relate to the French war, in which his administration had added new gems to the diadem of his sovereign. A recollection of the dangerous and difficult circumstances which had been encountered by the courage and subdued by the genius of his country, alleviated the burden of his declining years, and the light of those memories shone about him to the end. He died on the second of October, 1803, in the eighty-second year of his age.

Legacy[edit]

Mr. Adams, through the whole course of his life, was a zealous professor and an exemplary performer of the duties enjoined by the Christian religion. He viewed it not merely as a system of morals, but as a mysterious plan to exhibit the benevolence of the Almighty to his rational offspring on the earth, as the wise and benignant method to preserve an intercourse between earth and heaven. On this system he confided in the mercy of his Creator, and in this he had consolation while he saw his dissolution approaching.

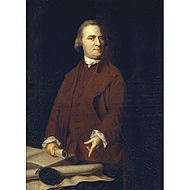

The face of Mr. Adams is known from the portrait by Copley. "He was of common size," says Sullivan, in his Familiar Letters on Public Characters, "of muscular form, light blue eyes, fair complexion, and erect in person. He wore a tie wig, cocked hat, and red cloak. His manner was very serious. At the close of his life, and probably from early times, he had a tremulous motion of the head, which probably added to the solemnity of his eloquence, as this was, in some measure, associated with his voice."

According to the ordinary custom of his country, Mr. Adams married early in life. Possessed of no hereditary fortune, and without a profession, he maintained his family chiefly by the salaries and emoluments of public office. Throughout the greater part of his life he was poor, until at a late period, in consequence of the death of his only son, he acquired a competency. His domestic economy, though plain, was by no means sordid, and his whole system of life exhibited a fair specimen of the genuine old-fashioned New England man. "He belonged to that class of men," said Edward Everett, "to whom the cause of civil and religious liberty, on both sides of the Atlantic, is mainly indebted for the great progress which it has made for the last two hundred years; and when the Declaration of Independence was signed, that dispensation might be considered as brought to a close. At a time when the new order of things was inducing laxity of manners and a departure from the ancient strictness, Samuel Adams clung with greater tenacity to the wholesome discipline of the fathers. His only relaxation from business and the cares of life was in the indulgence of a taste for sacred music, for which he was qualified by the possession of a most angelic voice and a soul solemnly impressed with religious sentiment. Resistance to oppression was his vocation."[9]

Quotes[edit]

- "The Utopian schemes of levelling, and a community of goods, are as visionary and impracticable, as those which vest all property in the Crown, are arbitrary, despotic, and in our government unconstitutional. Now, what property can the colonists be conceived to have, if their money may be granted away by others, without their consent?" - Letter to Dennys De Berdt, January 12, 1768

- "If you love wealth more than liberty, the tranquility of servitude better than the animating contest of freedom, depart from us in peace. We ask not your counsel nor your arms. Crouch down and lick the hand that feeds you. May your chains rest lightly upon you and may posterity forget that you were our countrymen." - Speech celebrating American Independence, August 1, 1776

- "May every citizen in the army and in the country, have a proper sense of the DEITY upon his mind, and an impression of that declaration recorded in the Bible, " Him that honoreth me I will honor, but he that despiseth me shall be lightly esteemed.""[10][11]

- "Constitution be never construed... to prevent the people of the United States who are peaceable citizens from keeping their own arms."[12]

- "May your chains sit lightly upon you, and may posterity forget that ye were our countrymen! [13]

- "When vain aspiring men possess highest seats in govt, country will need experienced patriots to prevent its ruin." [14]

- "While the People are virtuous they cannot be subdued; but when once they lose their Virtue they will be ready to surrender their Liberties to the first external or internal Invader." - Samuel Adams to James Warren (February 12, 1779)

- "How necessary is it, that the utmost pains be taken by the Publick, to have the Principles of Virtue early inculcated on the Minds even of Children, and the moral Sense kept alive, and that the wise Institutions of our Ancestors for these great Purposes be encouragd by the Government. For no People will tamely surrender their Liberties, nor can any be easily subdued, when Knowledge is diffusd and Virtue is preservd. On the Contrary, when People are universally ignorant, and debauchd in their Manners, they will sink under their own Weight without the Aid of foreign Invaders." [15]

Works[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ http://www.adherents.com/gov/Founding_Fathers_Religion.html

- ↑ http://ushistory.org/declaration/signers/adams_s.htm

- ↑ http://www.americansonsofliberty.com/samadams.htm

- ↑ Samuel Adams

- ↑ Birth of the Bill of Rights: Biographies

- ↑ Governor Samuel Adams

- ↑ http://www.americansonsofliberty.com/samadams.htm

- ↑ Samuel Adams: A Life, by Ira Stoll

- ↑ American Eloquence : a Collection of Speeches and Addresses

- ↑ 1 Samuel 2:30

- ↑ The Writings of Samuel Adams: 1778-1802, Boston Gazette, June 12, 1780

- ↑ A proposal that Adams made in 1788. p 267

- ↑ The World’s Famous Orations. America: I. (1761–1837). 1906.

- ↑ The Writings of Samuel Adams: 1778-1802 - Page 213, Samuel Adams - History - 1908

- ↑ Samuel Adams to James Warren (November 4th, 1775)

External links[edit]

- Samuel Adams on the Right to Keep and Bear Arms

- The Life and Public Services of Samuel Adams

- Samuel Adams, by James Kendall Hosmer

- Works by Samuel Adams - text and free audio - LibriVox

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Categories: [Founding Fathers] [Taxation] [Tax Revolts] [Massachusetts Governors] [American Revolution] [Republicanism] [Early National U.S.] [Veterans] [Conservatives] [Conservatism] [Libertarianism] [Libertarians] [Congregationalists] [United States History] [Pro Second Amendment] [People Associated with Firearms] [American Gun Rights Advocates] [United States History Figures] [Patriots] [John Adams]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/22/2023 06:45:25 | 134 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Samuel_Adams | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF