Mexican War Of Independence

From Nwe

From Nwe | Mexican War of Independence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

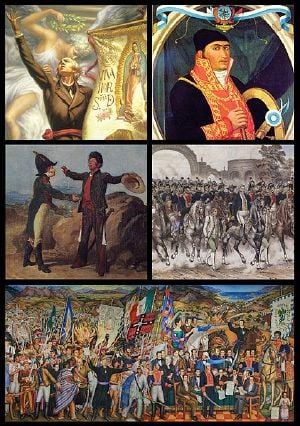

Clockwise from top left: Miguel Hidalgo, José María Morelos, Trigarante Army in Mexico City, Mural of independence by O'Gorman, Embrace of Acatempan between Iturbide and Guerrero |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

|

Mexico |

|

||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla Ignacio Allende Juan Aldama José María Morelos Ignacio López Rayón Mariano Matamoros Guadalupe Victoria Vicente Guerrero Agustín de Iturbide |

Félix María Calleja del Rey Juan Ruiz de Apodaca Ignacio Elizondo Agustín de Iturbide Antonio López de Santa Anna Juan O'Donoju |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 80,000 | 14,000 | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 15,000 deaths 450,000 wounded pro-independence insurgent supporters, including civilians. |

8,000 deaths | ||||||

Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821), was an armed conflict between the people of Mexico and Spanish colonial authorities, which started on September 16, 1810. The Mexican War of Independence movement was led by Mexican-born Spaniards, Mestizos, Zambos and Amerindians who sought independence from Spain. It started as an idealistic peasants' rebellion against their colonial masters, but finally ended as an unlikely alliance between "liberales" (liberals), and "conservadores" (conservatives).

The struggle for Mexican independence dates back to the conquest of Mexico, when Martín Cortés, son of Hernán Cortés and La Malinche, led a revolt against the Spanish colonial government in order to eliminate the issues of oppression and privileges for the conquistadors.[1] According to some historians, the struggle for Mexican Independence was re-ignited in December 1650 when an Irish adventurer by the name of William Lamport, escaped from the jails of the Inquisition in Mexico, and posted a "Proclamation of Independence from Spain" on the walls of the city. Lamport wanted Mexico to break with Spain, separate church and state and proclaim himself emperor of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. His ambitious idealist movement was soon terminated by the Spanish colonial authorities and Lamport was re-captured and executed for defamation.[2]

After the abortive Conspiracy of the Machetes in 1799, the war of Independence led by the Mexican-born Spaniards became a reality. The movement for independence was far from gaining unanimous support among Mexicans, who became divided between independentists, autonomists, and royalists. Lack of a consensus about how an independent Mexico would be governed meant that colonial repression would be replaced by that of elite Mexican rulers. Little changed for the vast majority of the population. The lesson of the Mexican War of Independence is that without a shared vision of how a just and fair government should be structured, a revolution can shed blood and sacrifice lives without actually achieving its goals of freedom, justice, and equality.

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla and the beginning of the independence movement

The founder and leader of the Mexican Independence movement was Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, the criollo Roman Catholic priest from the small town of Dolores. Soon after becoming a priest, Hidalgo y Costilla began to promote the idea of an uprising by criollo, mestizo, zambo, and Amerindian peasants against wealthy Spanish land-owners, and foreign aristocrats. Hidalgo y Costilla would earn the name "The Father of Mexican Independence."[3]

During his seven years at Dolores, Hidalgo y Costilla and several educated criollos organized secret discussion groups, where criollos, peninsulares, Amerindians, mestizos, zambos, and mulattos participated. The independence movement was founded over these informal meetings, which was directed against the Spanish colonial government, and foreign rulers of the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

Beginning of the war

After the conspirators were betrayed by a supporter, Hidalgo y Costilla declared war against the colonial government on the late night of September 15, 1810. At dawn of September 16, (the day now considered Mexico's Independence Day) the revolutionary army decided to strike for independence and marched on to Guanajuato, a major colonial mining center governed by Spaniards and criollos.[4] It was on September 16 that the famous "el grito de Dolores" was issued, effectively marking the beginning of the fight for Mexican independence.[5] There the leading citizens barricaded themselves in a warehouse. The rebel army captured the warehouse on September 28, and most of the Spaniards and criziollos were massacred or exiled. On October 30, 1810, Hidalgo y Costilla's army encountered Spanish resistance at the Battle of Monte de las Cruces, fought them and achieved victory.[6] However, the rebel army failed to defeat the large and heavily-armed Spanish army in Mexico City. Rebel survivors of the battle sought refuge in nearby provinces and villages. The insurgent forces planned a defensive strategy at a bridge on the Calderón River, pursued by the Spanish army.

In January 1811, Spanish forces fought the Battle of the Bridge of Calderón and defeated the insurgent army,[7] forcing the rebels to flee towards the United States-Mexican border, where they hoped to escape.[8] However they were intercepted by the Spanish army and Hidalgo y Costilla and his remaining soldiers were captured in the state of Jalisco, in the region known as "Los Altos." He faced court trial of the Inquisition and was found guilty of treason. He was executed by firing squad in Chihuahua, on July 31, 1811.[9] His body was mutilated, and his head was displayed in Guanajuato as a warning to rebels.[10]

José María Morelos and declaration of independence

Following the death of Hidalgo y Costilla, the leadership of the revolutionary army was assumed by José María Morelos, also a priest.[11] Under his leadership the cities of Oaxaca and Acapulco were occupied. In 1813, the Congress of Chilpancingo was convened and in November 6 of that year, the Congress signed the first official document of independence,[12] known as the "Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America." It was followed by a long period of war at the Siege of Cuautla. In 1815, Morelos was captured by Spanish colonial authorities and executed for treason in San Cristóbal Ecatepec on December 22.[13]

Guadalupe Victoria and Vicente Guerrero guerrilla warfare

Between 1815 to 1821, most of the fighting by those seeking independence from Spain was done by isolated guerrilla groups. Out of these groups rose two soldiers, Guadalupe Victoria in Puebla and Vicente Guerrero in Oaxaca,[14] both of whom were able to command allegiance and respect from their followers. The Spanish viceroy, however, felt the situation was under control and issued a pardon to every rebel soldier and follower who would surrender.

Javier Mina, a Spanish political figure exiled from Spain because of his opposition to King Ferdinand VII's policies, decided Mexico would be the best platform to fight against the king and gathered an army that provoked serious problems to the Viceroy government in 1816.[15][16]

The rebels faced heavy Spanish military resistance. Encouraged by Hidalgo y Costilla and Morelos's irregular armies, the criollo, mestizo, zambo and Amerindian rebels reinforced fears of racial and class warfare, ensuring their grudging acquiescence to the Spanish colonial government, and foreign aristocrats until independence could be achieved. It was at this event that the machinations of a conservative military caudillo coinciding with a successful liberal rebellion in Spain made possible a radical realignment of the independence forces.

In what was supposed to be the final Spanish campaign against the revolutionary army in December 1820, the Viceroy of New Spain Juan Ruiz de Apodaca sent an army led by a Spanish criollo officer, Agustín de Iturbide, to defeat Guerrero's army in Oaxaca.[17]

Ferdinand VII of Spain

Iturbide's campaign to the Oaxacan region coincided with a successful military coup d'état in Spain against the new monarchy of King Ferdinand VII who had returned to power after being imprisoned by Napoleon I of France after he had invaded Spain in 1808. The coup leaders, who had been assembled an expeditionary force to suppress the Mexican independence movements, compelled a reluctant King Ferdinand VII to sign a liberal Spanish constitution. When news of the liberal charter reached Mexico, Iturbide saw in it both a threat to the status quo and an opportunity for the criollos to gain control of Mexico.[17] Ironically, independence was finally achieved when forces in the colonies chose to rise up against a temporarily liberal regime in Spain. After an initial clash with Guerrero's army, Iturbide switched allegiances and invited the rebel leader to meet and discuss principles of a renewed independence struggle.

While stationed in the town of Iguala, Iturbide proclaimed three principles, or "guarantees," for Mexico's independence from Spain. The document, known as the Plan de Iguala,[18] declared that Mexico would be independent, its religion is to be Roman Catholicism, and its inhabitants were to be united, without distinction between Mexican and European. It stipulated further that Mexico would become a constitutional monarchy under King Ferdinand VII, he or some Spanish or other European king would occupy the throne in Mexico City, and an interim junta would draw up regulations for the election of deputies to a congress, which would write a constitution for the monarchy. The plan was so broadly based that it pleased both patriots and loyalists. The goal of independence and the protection of Roman Catholicism brought together all factions.

Independence and aftermath

Iturbide's army was joined by rebel forces from all over Mexico. When the rebels' victory became certain, the Viceroy of New Spain resigned.[19] On August 24, 1821, representatives of the Spanish crown and Iturbide signed the Treaty of Córdoba, which recognized Mexican independence under the terms of the Plan de Iguala, ending three centuries of Spanish colonial rule.[20]

During the struggle for independence, Mexico lost one-tenth of its citizens. In the decade following separation from Spanish rule, Mexico saw a drastic decline in its gross domestic product (GDP), per capital income, and amount of foreign trade.[21]

Notes

- ↑ John Charles Chasteen, Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 2001, ISBN 0393050483).

- ↑ Ryan Dominic Crewe, Lamport, William (Guillén Lombardo) (1610-1659) Irish Migration Studies in Latin America 5(1)(March 2007): 74-76. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ Arthur Howard Noll, A Short History of Mexico (Andesite Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1376335354), 148.

- ↑ Noll, 149-151.

- ↑ Noll, 150-151.

- ↑ Noll, 153.

- ↑ Noll, 155-156.

- ↑ Philip Young, History of Mexico, Her Civil Wars, and Colonial and Revolutionary Annals (Wentworth Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1362979036), 84-86.

- ↑ Noll, 156.

- ↑ Jim Tuck, Miguel Hidalgo: the Father who fathered a country (1753–1811) Mex Connect, October 9, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ Noll, 157.

- ↑ Noll, 161-162.

- ↑ Noll, 163.

- ↑ Noll, 161.

- ↑ Jim Tuck, Javier Mina (1789–1818) Mex Connect, October 9, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ↑ Noll, 166.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Noll, 171.

- ↑ Noll, 172.

- ↑ Noll, 173.

- ↑ Noll, 174, 176-177.

- ↑ Steven Mintz (ed.), Mexican American Voices: A Documentary Reader (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, ISBN 978-1405182591).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chasteen, John Charles. Born in Blood and Fire: A Concise History of Latin America. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 2001. ISBN 0393050483

- Mintz, Steven (ed.). Mexican American Voices: A Documentary Reader. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. ISBN 978-1405182591

- Noll, Arthur Howard. A Short History of Mexico. Andesite Press, 2017 (original 1890). ISBN 978-1376335354

- Stein, R. Conrad. The Mexican War of Independence. Morgan Reynolds Pub., 2007. ISBN 978-1599350547

- Young, Philip. History of Mexico, Her Civil Wars, and Colonial and Revolutionary Annals. Wentworth Press, 2016 (original 1850). ISBN 978-1362979036

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- Mexican War of Independence Texas State Historical Association

- Mexican War of Independence begins, September 16, 1810 History.com

- Mexico's Independence Day marks the beginning of a decade-long revolution National Geographic

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 04:47:47 | 40 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mexican_War_of_Independence | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF