Himalaya

From Britannica 11th Edition (1911)

From Britannica 11th Edition (1911) Himalaya, the name given to the mountains which form the northern boundary of India. The word is Sanskrit and literally signifies “snow-abode,” from him, snow, and álaya, abode, and might be translated “snowy-range,” although that expression is perhaps more nearly the equivalent of Himachal, another Sanskrit word derived from him, snow, and áchal, mountain, which is practically synonymous with Himalaya and is often used by natives of northern India. The name was converted by the Greeks into Emodos and Imaos.

Modern geographers restrict the term Himalaya to that portion of the mountain region between India and Tibet enclosed within the arms of the Indus and the Brahmaputra. From the bend of the Indus southwards towards the plains of the Punjab to the bend of the Brahmaputra southwards towards the plains of Assam, through a length of 1500 m., is Himachal or Himalaya. Beyond the Indus, to the north-west, the region of mountain ranges which stretches to a junction with the Hindu Kush south of the Pamirs, is usually known as Trans-Himalaya. Thus the Himalaya represents the southern face of the great central upheaval—the plateau of Tibet—the northern face of which is buttressed by the Kuen Lun.

Throughout this vast space of elevated plateau and mountain face geologists now trace a system of main chains, or axes, extending from the Hindu Kush to Assam, Structure of the Himalaya. arranged in approximately parallel lines, and traversed at intervals by main lines of drainage obliquely. Godwin-Austen indicates six of these geological axes as follows:

1. The main Central Asian axis, the Kuen Lun forming the northern edge or ridge of the Tibetan plateau.

2. The Trans-Himalayan chain of Muztagh (or Karakoram), which is lost in the Tibetan uplands, passing to the north of the sources of the Indus.

3. The Ladakh chain, partly north and partly south of the Indus—for that river breaks across it about 100 m. above Leh. This chain continues south of the Tsanpo (or Upper Brahmaputra), and becomes part of the Himalayan system.

4. The Zaskar, or main chain of the Himalaya, i.e. the “snowy range” par excellence which is indicated by Nanga Parbat (overlooking the Indus), and passes in a south-east direction to the southern side of the Deosai plains. Thence, bending slightly south, it extends in the line of snowy peaks which are seen from Simla to the famous peaks of Gangotri and Nanda Devi. This is the best known range of the Himalaya.

5. The outer Himalaya or Pir Panjal-Dhaoladhar ridge.

6. The Sub-Himalaya, which is “easily defined by the fringing line of hills, more or less broad, and in places very distinctly marked off from the main chain by open valleys (dhúns) or narrow valleys, parallel to the main axis of the chain.” These include the Siwaliks.

Interspersed between these main geological axes are many other minor ridges, on some of which are peaks of great elevation. In fact, the geological axis seldom coincides with the line of highest elevation, nor must it be confused with the main lines of water-divide of the Himalaya.

On the north and north-west of Kashmir the great water-divide which separates the Indus drainage area from that of the Yarkand and other rivers of Chinese Turkestan has been explored by Sir F. Younghusband, and subsequently The great northern watershed of India. by H. H. P. Deasy. The general result of their investigations has been to prove that the Muztagh range, as it trends south-eastwards and finally forms a continuous mountain barrier together with the Karakoram, is the true water-divide west of the Tibetan plateau. Shutting off the sources of the Indus affluents from those of the Central Asian system of hydrography, this great water-parting is distinguished by a group of peaks of which the altitude is hardly less than that of the Eastern Himalaya. Mount Godwin-Austen (28,250 ft. high), only 750 ft. lower than Everest, affords an excellent example in Asiatic geography of a dominating, peak-crowned water-parting or divide. From Kailas on the far west to the extreme north-eastern sources of the Brahmaputra, the great northern water-parting of the Indo-Tibetan highlands has only been occasionally touched. Littledale, du Rhins and Bonvalot may have stood on it as they looked southwards towards Lhasa, but for some 500 or 600 m. east of Kailas it appears to be lost in the mazes of the minor ranges and ridges of the Tibetan plateau. Nor can it be said to be as yet well defined to the east of Lhasa.

The Tibetan plateau, or Chang, breaks up about the meridian of 92° E., and to the east of this meridian the affluents of the Tsanpo (the same river as the Dihong and subsequently as the Brahmaputra) drain no longer from the elevated Eastern Tibet. plateau, but from the rugged slopes of a wild region of mountains which assumes a systematic conformation where its successive ridges are arranged in concentric curves around the great bend of the Brahmaputra, wherein are hidden the sources of all the great rivers of Burma and China. Neither immediately beyond this great bend, nor within it in the Himalayan regions lying north of Assam and east of Bhutan, have scientific investigations yet been systematically carried out; but it is known that the largest of the Himalayan affluents of the Brahmaputra west of the bend derive their sources from the Tibetan plateau, and break down through the containing bands of hills, carrying deposits of gold from their sources to the plains, as do all the rivers of Tibet.

Although the northern limits of the Tsanpo basin are not sufficiently well known to locate the Indo-Tibetan watershed even approximately, there exists some scattered evidence of the nature of that strip of Northern Himalaya Himalaya north of the central chain of snowy peaks. on the Tibeto-Nepalese border which lies between the line of greatest elevation and the trough of the Tsanpo. Recent investigations show that all the chief rivers of Nepal flowing southwards to the Tarai take their rise north of the line of highest crests, the “main range” of the Himalaya; and that some of them drain long lateral high-level valleys enclosed between minor ridges whose strike is parallel to the axis of the Himalaya and, occasionally, almost at right angles to the course of the main drainage channels breaking down to the plains. This formation brings the southern edge of the Tsanpo basin to the immediate neighbourhood of the banks of that river, which runs at its foot like a drain flanking a wall. It also affords material evidence of that wrinkling or folding action which accompanied the process of upheaval, when the Central Asian highlands were raised, which is more or less marked throughout the whole of the north-west Indian borderland. North of Bhutan, between the Himalayan crest and Lhasa, this formation is approximately maintained; farther east, although the same natural forces first resulted in the same effect of successive folds of the earth’s crust, forming extensive curves of ridge and furrow, the abundant rainfall and the totally distinct climatic conditions which govern the processes of denudation subsequently led to the erosion of deeper valleys enclosed between forest-covered ranges which rise steeply from the river banks.

Although suggestions have been made of the existence of higher peaks north of the Himalaya than that which dominates the Everest group, no evidence has been adduced to support such a contention. On the other hand the Height of Himalayan peaks. observations of Major Ryder and other surveyors who explored from Lhasa to the sources of the Brahmaputra and Indus, at the conclusion of the Tibetan mission in 1904, conclusively prove that Mount Everest, which appears from the Tibetan plateau as a single dominating peak, has no rival amongst Himalayan altitudes, whilst the very remarkable investigations made by permission of the Nepal durbar from peaks near Kathmandu in 1903, by Captain Wood, R.E., not only place the Everest group apart from other peaks with which they have been confused by scientists, isolating them in the topographical system of Nepal, but clearly show that there is no one dominating and continuous range indicating a main Himalayan chain which includes both Everest and Kinchinjunga. The main features of Nepalese topography are now fairly well defined. So much controversy has been aroused on the subject of Himalayan altitudes that the present position of scientific analysis in relation to them may be shortly stated. The heights of peaks determined by exact processes of trigonometrical observation are bound to be more or less in error for three reasons: (1) the extraordinary geoidal deformation of the level surface at the observing stations in submontane regions; (2) ignorance of the laws of refraction when rays traverse rarefied air in snow-covered regions; (3) ignorance of the variations in the actual height of peaks due to the increase, or decrease, of snow. The value of the heights attached to the three highest mountains in the world are, for these reasons, adjudged by Colonel S. G. Burrard, the Supt. Trigonometrical Surveys in India, to be in probable error to the following extent:

| Present Survey Value of Height | Most probable Value. | |

| Mount Everest | 29,002 | 29,141 |

| K2 (Godwin Austen) | 28,250 | 28,191 |

| Kinchinjunga | 28,146 | 28,225 |

These determinations have the effect of placing Kinchinjunga second and K2 third on the list.

Geology.—The Himalaya have been formed by violent crumpling of the earth’s crust along the southern margin of the great tableland of Central Asia. Outside the arc of the mountain chain no sign of this crumpling is to be detected except in the Salt Range, and the Peninsula of India has been entirely free from folding of any importance since early Palaeozoic times, if not since the Archean period itself. But the contrast between the Himalaya and the Peninsula is not confined to their structure: the difference in the rocks themselves is equally striking. In the Himalaya the geological sequence, from the Ordovician to the Eocene, is almost entirely marine; there are indeed occasional breaks in the series, but during nearly the whole of this long period the Himalayan region, or at least its northern part, must have been beneath the sea—the Central Mediterranean Sea of Neumayr or Tethys of Suess. In the peninsula, however, no marine fossils have yet been found of earlier date than Jurassic and Cretaceous, and these are confined to the neighbourhood of the coasts; the principal fossiliferous deposits are the plant-bearing beds of the Gondwana series, and there can be no doubt that, at least since the Carboniferous period, nearly the whole of the Peninsula has been land. Between the folded marine beds of the Himalaya and the nearly horizontal strata of the peninsula lies the Indo-Gangetic plain, covered by an enormous thickness of alluvial and wind-blown deposits of recent date. The deep boring at Lucknow passed through 1336 ft. of sands—reaching nearly to 1000 ft. below sea-level—without any sign of approaching the base of the alluvial series. It is clear, then, that in front of the Himalaya there is a great depression, but as yet there is no indication that this depression was ever beneath the sea.

In the light thrown by recent researches on the structure and origin of mountain chains the explanation of these facts is no longer difficult. From early Palaeozoic times the peninsula of India has been dry land, a part, indeed, of a great continent which in Mesozoic times extended across the Indian Ocean towards South Africa. Its northern shores were washed by the Sea of Tethys, which, at least in Jurassic and Cretaceous times, stretched across the Old World from west to east, and in this sea were laid down the marine deposits of the Himalaya. The tangential pressures which are known to be set up in the earth’s crust—either by the contraction of the interior or in some other way—caused the deposits of this sea to be crushed up against the rigid granites and other old rocks of the peninsula and finally led to the whole mass being pushed forward over the edge of the part which did not crumple. The Indo-Gangetic depression was formed by the weight of the over-riding mass bending down the edge over which it rode, or else it is the lower limb of the S-shaped fold which would necessarily result if there were no fracture—the Himalaya representing the upper limb of the S.

Geologically, the Himalaya may be divided into three zones which correspond more or less with orographical divisions. The northern zone is the Tibetan, in which fossiliferous beds of Palaeozoic and Mesozoic age are largely developed—excepting in the north-west no such rocks are known on the southern flanks. The second is the zone of the snowy peaks and of the lower Himalaya, and is composed chiefly of crystalline and metamorphic rocks together with unfossiliferous sedimentary beds supposed to be of Palaeozoic age. The southern zone comprises the Sub-Himalaya and consists entirely of Tertiary beds, and especially of the upper Tertiaries. The oldest beds which have hitherto yielded fossils, belong to the Ordovician system, but it is highly probable that the underlying “Haimantas” of the central Himalaya are of Cambrian age. From these beds up to the top of the Carboniferous there appears to be no break; but the Carboniferous beds were in some places eroded before the deposition of the Productus shales, which belong to the Permian period. It is, however, possible that this erosion was merely local, for in other places there seems to be a complete passage from the Carboniferous to the Permian. From the Permian to the Lias the sequence in the central Himalaya shows no sign of a break, nor has any unconformity been proved between the Liassic beds and the overlying Spiti shales, which contain fossils of Middle and Upper Jurassic age. The Spiti shales are succeeded conformably by Cretaceous beds (Gieumal sandstone below and Chikkim limestone above), and these are followed without a break by Nummulitic beds of Eocene age, much disturbed and altered by intrusions of gabbro and syenite. Thus, in the Spiti area at least, there appears to have been continuous deposition of marine beds from the Permian Productus shales to the Eocene Nummulitic formation. The next succeeding deposit is a sandstone, often highly inclined, which rests unconformably upon the Nummulitic beds and resembles the Lower Siwaliks of the Sub-Himalaya (Pliocene) but which as yet has yielded no fossils of any kind. The whole is overlaid unconformably by the younger Tertiaries of Hundes, which are perfectly horizontal and have been quite unaffected by any of the folds.

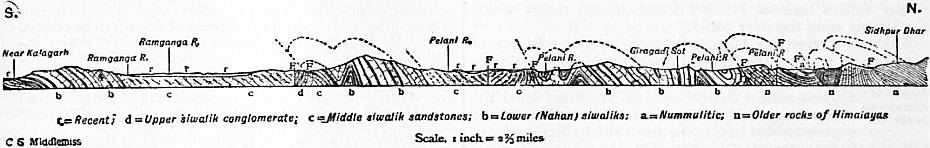

From the absence of any well-marked unconformity it is evident that in the northern part of the Himalayan belt, at least in the Spiti area, there can have been no post-Archaean folding of any magnitude until after the deposition of the Nummulitic beds, and that the folding was completed before the later Tertiaries of Hundes were laid down. It was, therefore, during the Miocene period that the elevation of this part of the chain began, while the disturbance of the Siwalik-like sandstone indicates that the folding continued into the Pliocene period. Along the southern flanks of the Himalaya the history of the chain is still more clearly shown. The sub-Himalaya are formed of Tertiary beds, chiefly Siwalik or upper Tertiary, while the lower Himalaya proper consist mainly of pre-Tertiary rocks without fossils. Throughout the whole length of the chain, wherever the junction of the Siwaliks with the pre-Tertiary rocks has been seen, it is a great reversed fault. West of the Blas river a similar reversed fault forms the boundary between the lower Tertiaries and the pre-Tertiary rocks of the Himalaya, while between the Sutlej and the Jumna rivers, where the lower Tertiaries help to form the lower Himalaya, the fault lies between them and the Siwaliks. The hade of the fault is constantly inwards, towards the centre of the chain, and the older rocks which form the Himalaya proper, have been pushed forward over the later beds of the sub-Himalaya. But the fault is more than an ordinary reversed fault: it was, nearly everywhere, the northern boundary of deposition of the Siwalik beds, and only in a few instances do any of the Siwalik deposits extend even to a short distance beyond it. The fault in fact was being formed during the deposition of the Siwalik beds, and as the beds were laid down, the Himalaya were pushed forward over them, the Siwaliks themselves being folded and upturned during the process. Accordingly, in some places the Siwaliks now form a continuous and conformable series from base to summit, in other places the middle beds are absent and the upper beds of the series rest upon the upturned and denuded edges of the lower beds. The Siwaliks are fluviatile and torrential deposits similar to those which are now being formed at the foot of the mountains, in the Indo-Gangetic plain; and their relations to the older rocks of the Himalaya proper were very similar to those which now exist between the deposits of the plain and the Siwaliks themselves. But the great fault just described is not the only one of this character. There is a series of such faults, approximately parallel to one another, and although they have not been traced throughout the whole chain, yet wherever they occur they seem to have formed the northern boundary of deposition of the deposits immediately to the south of them. It appears, therefore, that the Himalaya grew southwards in a series of stages. A reversed fault was formed at the foot of the chain, and upon this fault the mountains were pushed forward over the beds deposited at their base, crumpling and folding them in the process, and forming a sub-Himalayan ridge in front of the main chain. After a time a new fault originated at the foot of the sub-Himalayan zone thus raised, which now became part of the Himalaya themselves, and a new sub-Himalayan chain was formed in front of the previous one. The earthquakes of the present day show that the process is still in operation, and in time the deposits of the present Indo-Gangetic plain will be involved in the folds.

The regular form of the Himalaya, constituting an arc of a true circle, appears to indicate that the whole chain has been pushed forward as one mass upon a gigantic thrust-plane; but, if so, the dip of the plane must be low, for a line drawn along the southern foot of the Himalaya would coincide with the outcrop of a plane inclined to the surface at an angle of about 14°. The thrust-plane, then, does not coincide with any of the boundary faults already mentioned, which are usually inclined at angles of 50° or 60°. The latter are due to the fact that, although, perhaps, the whole mass above the thrust-plane may move, yet the pressure which pushes it forwards necessarily proceeds from behind. The back, accordingly, moves faster than the front, and the whole is packed together; as when an ice-floe drives against the shore, the ice breaks and the outer fragments ride over those within. The great thrust-plane which is thus imagined to exist at the base of the Himalaya, corresponds with the “major thrusts” of the N.W. Highlands of Scotland, and the reversed faults which appear at the surface with the “minor thrusts.”

Such is the general outline of Himalayan evolution as now understood, and the process of it has led to certain marked features of scenery and topography. Within the area of the trans-Indus mountains we have beds of hard limestone or sandstone Topographical results of evolution. alternating with soft shales, which leads to the scooping out by erosion of long narrow valleys where the shales occur, and the passage of the streams through deep rifts or gorges across the hard limestone anticlinals, which stand in irregular series of parallel ridges with the eroded valleys between. The great mass of the Himalaya exhibits the same structure, due to the same conditions acting for longer periods and on a much larger scale; but the structure is varied in the eastern portions of the mountains by the effect of different climatic conditions, and especially by the greater rainfall. Instead of wide, barren, wind-swept valleys, here are found fertile alluvial plains—such as Manipur—but for the most part the erosive action of the river has been able to keep pace with the rise of the river bed, and we have deep, steep-sided valleys arranged between the same parallel system of folds as we see on the western frontier, connected by short transverse gaps where the rivers cross the folds, frequently to resume a course parallel to that originally held. An instance of this occurs where the Indus suddenly breaks through the well-defined Ladakh range in the North-west Himalaya to resume its north-westerly course after passing from the northern to the southern side of the range. The reason assigned for these extraordinary diversions of the drainage right across the general strike of the ridges is that it is antecedent—i.e. that the lines of drainage were formed ere the folds or anticlinals were raised; and that the drainage has merely maintained the course originally held, by the power of erosion during the gradual process of upheaval.

In the outer valleys of the Himalaya the sides are generally steep, so steep as to be liable to landslip, whilst the streams are still cutting down the river beds and have not yet reached the stage of equilibrium. Here and there a valley has become filled with alluvial detritus owing to some local impediment in the drainage, and when this occurs there is usually to be found a fertile and productive field for agriculture. The straits of the Jhelum, below Baramulla, probably account for the lovely vale of Kashmir, which is in form (if not in principles of construction) a repetition on grand scale of the Maidan of the Afridi Tirah, where the drainage from the slopes of a great amphitheatre of hills is collected and then arrested by the gorge which marks the outlet to the Bara.

Other rivers besides the Indus and the Brahmaputra begin by draining a considerable area north of the snowy range—the Sutlej, the Kosi, the Gandak and the Subansiri, for example. All these rivers break through the main snowy range ere General Himalayan formation is typical. they twist their way through the southern hills to the plains of India. Here the “antecedent” theory will not suffice, for there is no sufficient catchment area north of the snows to support it. Their formation is explained by a process of “cutting back,” by which the heads of these streams are gradually eating their way northwards owing to the greater rainfall on the southern than on the northern slopes. The result of this process is well exhibited in the relative steepness of slope on the Indian and Tibetan sides of the passes to the Indus plateau. On the southern or Indian side the routes to Tibet and Ladakh follow the levels of Himalayan valleys with no remarkably steep gradients till they near the approach to the water-divide. The slope then steepens with the ascending curve to the summit of the pass, from which point it falls with a comparatively gentle gradient to the general level of the plateau. The Zoji La, the Kashmir water-divide between the Jhelum and the Indus, is a prominent case in point, and all the passes from the Kumaon and Garhwal hills into Tibet exhibit this formation in a marked degree. Taking the average elevation of the central axial line of snowy peaks as 19,000 ft., the average height of the passes is not more than 10,000 owing to this process of cutting down by erosion and gradual encroachment into the northern basin.

|

| Section across the sub-Himalayan zone. |

Meteorology.—Independently of the enormous variety of topographical conformation contained in the Himalayan system, the vast altitude of the mountains alone is sufficient to cause modifications of climate in ascending over their slopes such as are not surpassed by those observed in moving from the equator to the poles. One half of the total mass of the atmosphere and three-fourths of the water suspended in it in the form of vapour lie below the average altitude of the Himalaya; and of the residue, one-half of the air and virtually almost all the vapour come within the influence of the highest peaks. The regular variations in pressure of the air indicated by the barometer and the annual and diurnal oscillations are as well marked in the Himalaya as elsewhere, but the amount of vapour held in suspension diminishes so rapidly with the altitude that not more than one-sixth (sometimes only one-tenth) of that observed at the foot of the mountains is found at the greatest heights. This is dependent on the temperature of the air which rapidly decreases with altitude. On the mountains every altitude has its corresponding temperature, an elevation of 1000 ft. producing a fall of 3½°, or about 1° to each 300 ft. The mean winter temperature at 7000 ft. (which is about the average height of Himalayan “hill stations”) is 44° F. and the summer mean about 65° F. At 9000 ft. the mean temperature of the coldest month is 32° F. At 12,000 ft. the thermometer never falls below freezing-point from the end of May to the middle of October, and at 15,000 ft. it is seldom above that point even in the height of summer. It should be noted that the thermometrical conditions of Tibet vary considerably from those of the Himalaya. At 12,000 ft. in Tibet the mean of the hottest month is about 60° F. and of the coldest about 10° F. whilst, at 15,000 ft. the frost is only permanent from the end of October to the end of April. The distribution of vegetation and topographical conformation largely influence the question of local temperature. For instance it may be found that the difference of temperature between forest-clad ranges and the Indian plains is twice as much in April and May as in December or January; and the difference between the temperature of a well-wooded hill top and the open valley below may vary from 9° to 24° within twenty-four hours. The general relations of temperature to altitude as determined by Himalayan observations are as follows: (1) The decrease of temperature with altitude is most rapid in summer. (2) The annual range diminishes with the elevation. (3) The diurnal range diminishes with the elevation. Comparisons are, however, apt to become anomalous when applied to elevated zones with a dense covering of forest and a great quantity of cloud and open and uncloudy regions both above and below the forest-clad tracts.

The chief rainfall occurs in the summer months between May and October (i.e. the period of the monsoon rains of India), the remainder of the year being comparatively dry. The fall of rain over the great plain of northern India gradually diminishes Rainfall. in quantity, and begins later, as we pass from east to west. At the same time the rain is heavier as we approach the Himalaya and the greatest falls are measured in its outer ranges; but the quantity again diminishes as we pass onward across the chain, and on arriving at the border of Tibet, behind the great line of snowy peaks, the rain falls in such small quantities as to be hardly susceptible of measurement. Diurnal currents of wind, which are established from the plains to the mountains during the day, and from the hills to the plains during the night, are important agents in distributing the rainfall. The condensation of vapour from the ascending currents and their gradual exhaustion as they are precipitated on successive ranges is very obvious in the cloud effects produced during the monsoon, the southern or windward face of each range being clothed day after day with a white crest of cloud whilst the northern slopes are often left entirely free. This shows how large a proportion of the vapour is arrested and how it is that only by drifting through the deeper gorges can any moisture find its way to the Tibetan table-land.

The yearly rainfall, which amounts to between 60 and 70 in. in the delta of the Ganges, is reduced to about 40 in. when that river issues from the mountains, and diminishes to 30 in. at the debouchment of the Indus into the plains. At Darjeeling (7000 ft. altitude) on the outer ranges of the eastern Himalaya it amounts to about 120 in. At Naini Tal north of the United Provinces it is about 90 in.; at Simla about 80 in., diminishing still further as one approaches the north-western hills. All these stations are about the same altitude.

In the eastern Himalaya the ordinary winter limit of snow is 6000 ft. and it never lies for many days even at 7000 ft. In Kumaon, on the west, it usually reaches down to the 5000 ft. level and occasionally to 2500 ft. Snow has been known to Snowfall. fall at Peshawar. At Leh, in western Tibet, hardly 2 ft. of snow are usually registered and the fall on the passes between 17,000 and 19,000 ft. is not generally more than 3 ft., but on the Himalayan passes farther east the falls are much heavier. Even in September these passes may be quite blocked and they are not usually open till the middle of June. The snow-line, or the level to which snow recedes in the course of the year, ranges from 15,000 to 16,000 ft. on the southern exposures of the Himalaya that carry perpetual snow, along all that part of the system that lies between Sikkim and the Indus. It is not till December that the snow begins to descend for the winter, although after September light falls occur which cover the mountain sides down to 12,000 ft., but these soon disappear. On the snowy range the snow-line is not lower than 18,500 ft. and on the summit of the table-land it reaches to 20,000 ft. On all the passes into Tibet vegetation reaches to about 17,500 ft., and in August they may be crossed in ordinary years up to 18,400 ft. without finding any snow upon them; and it is as impossible to find snow in the summer in Tibet at 15,500 ft. above the sea as on the plains of India.

Glaciers.—The level to which the Himalayan glaciers extend is greatly dependent on local conditions, principally the extent and elevation of the snow basins which feed them, and the slope and position of the mountain on which they are formed. Glaciers on the outer slopes of the Himalaya descend much lower than is commonly the case in Tibet, or in the most elevated valleys near the snowy range. The glaciers of Sikkim and the eastern mountains are believed not to reach a lower level than 13,500 or 14,000 ft. In Kumaon many of them descend to between 11,500 and 12,500 ft. In the higher valleys and Tibet 15,000 and 16,000 ft. is the ordinary level at which they end, but there are exceptions which descend far lower. In Europe the glaciers descend between 3000 and 5000 ft. below the snow-line, and in the Himalaya and Tibet about the same holds good. The summer temperatures of the points where the glaciers end on the Himalaya also correspond fairly with those of the corresponding positions in European glaciers, viz. for July a little below 60° F., August 58° and September 55°.

Measurements of the movement of Himalayan glaciers give results according closely with those obtained under analogous conditions in the Alps, viz. rates from 9½ to 14¼ in. in twenty-four hours. The motion of one glacier from the middle of May to the middle of October averaged 8 in. in the twenty-four hours. The dimensions of the glaciers on the outer Himalaya, where, as before remarked, the valleys descend rapidly to lower levels, are fairly comparable with those of Alpine glaciers, though frequently much exceeding them in length—8 or 10 m. not being unusual. In the elevated valleys of northern Tibet, where the destructive action of the summer heat is far less, the development of the glaciers is enormous. At one locality in north-western Ladakh there is a continuous mass of snow and ice extending across a snowy ridge, measuring 64 m. between the extremities of the two glaciers at its opposite ends. Another single glacier has been surveyed 36 m. long.

The northern tributaries of the Gilgit river, which joins the Indus near its south-westerly bend towards the Punjab, take their rise from a glacier system which is probably unequalled in the world for its extent and magnificent proportions. Chief amongst them are the glaciers which have formed on the southern slopes of the Muztagh mountains below the group of gigantic peaks dominated by Mount Godwin-Austen (28,250 ft. high). The Biafo glacier system, which lies in a long narrow trough extending south-west from Nagar on the Hunza to near the base of the Muztagh peaks, may be traced for 90 m. between mountain walls which tower to a height of from 20,000 to 25,000 ft. above sea-level on either side.

In connexion with almost all the Himalayan glaciers of which precise accounts are forthcoming are ancient moraines indicating some previous condition in which their extent was much larger than now. In the east these moraines are very remarkable, extending 8 or 10 m. In the west they seem not to go beyond 2 or 3 m. reach. They have been observed on the summit of the table-land as well as on the Himalayan slope. The explanation suggested to account for the former great extension of glaciers in Norway would seem applicable here. Any modification of the coast-line which should submerge the area now occupied by the North Indian plain, or any considerable part of it, would be accompanied by a much wetter and more equable climate on the Himalaya; more snow would fall on the highest ranges, and less summer heat would be brought to bear on the destruction of the glaciers, which would receive larger supplies and descend lower.

Botany.—Speaking broadly, the general type of the flora of the lower, hotter and wetter regions, which extend along the great plain at the foot of the Himalaya, and include the valleys of the larger rivers which penetrate far into the mountains, does not differ from that of the contiguous peninsula and islands, though the tropical and insular character gradually becomes less marked going from east to west, where, with a greater elevation and distance from the sea and higher latitude, the rainfall and humidity diminish and the winter cold increases. The vegetation of the western part of the plain and of the hottest zone of the western mountains thus becomes closely allied to, or almost identical with, that of the drier parts of the Indian peninsula, more especially of its hilly portions; and, while a general tropical character is preserved, forms are observed which indicate the addition of an Afghan as well as of an African element, of which last the gay lily Gloriosa superba is an example, pointing to some previous connexion with Africa.

The European flora, which is diffused from the Mediterranean along the high lands of Asia, extends to the Himalaya; many European species reach the central parts of the chain, though few reach its eastern end, while genera common to Europe and the Himalaya are abundant throughout and at all elevations. From the opposite quarter an influx of Japanese and Chinese forms, such as the rhododendrons, the tea plant, Aucuba, Helwingia, Skimmia, Adamia, Goughia and others, has taken place, these being more numerous in the east and gradually disappearing in the west. On the higher and therefore cooler and less rainy ranges of the Himalaya the conditions of temperature requisite for the preservation of the various species are readily found by ascending or descending the mountain slopes, and therefore a greater uniformity of character in the vegetation is maintained along the whole chain. At the greater elevations the species identical with those of Europe become more frequent, and in the alpine regions many plants are found identical with species of the Arctic zone. On the Tibetan plateau, with the increased dryness, a Siberian type is established, with many true Siberian species and more genera; and some of the Siberian forms are further disseminated, even to the plains of Upper India. The total absence of a few of the more common forms of northern Europe and Asia should also be noticed, among which may be named Tilia, Fagus, Arbutus, Erica, Azalea and Cistacae.

In the more humid regions of the east the mountains are almost everywhere covered with a dense forest which reaches up to 12,000 or 13,000 ft. Many tropical types here ascend to 7000 ft. or more. To the west the upper limit of forest is somewhat lower, from 11,500 to 12,000 ft. and the tropical forms usually cease at 5000 ft.

In Sikkim the mountains are covered with dense forest of tall umbrageous trees, commonly accompanied by a luxuriant growth of under shrubs, and adorned with climbing and epiphytal plants in wonderful profusion. In the tropical zone large figs abound, Terminalia, Shorea (sál), laurels, many Leguminosae, Bombax, Artocarpus, bamboos and several palms, among which species of Calamus are remarkable, climbing over the largest trees; and this is the western limit of Cycas and Myristica (nutmeg). Plantains ascend to 7000 ft. Pandanus and tree-ferns abound. Other ferns, Scitamineae, orchids and climbing Aroideae are very numerous, the last named profusely adorning the forests with their splendid dark-green foliage. Various oaks descend within a few hundred feet of the sea-level, increasing in numbers at greater altitudes, and becoming very frequent at 4000 ft., at which elevation also appear Aucuba, Magnolia, cherries, Pyrus, maple, alder and birch, with many Araliaceae, Hollböllea, Skimmia, Daphne, Myrsine, Symplocos and Rubus. Rhododendrons begin at about 6000 ft. and become abundant at 8000 ft., from 10,000 to 14,000 ft. forming in many places the mass of the shrubby vegetation which extends some 2000 ft. above the forest. Epiphytal orchids are extremely numerous between 6000 and 8000 ft. Of the Coniferae, Podocarpus and Pinus longifolia alone descend to the tropical zone; Abies Brunoniana and Smithiana and the larch (a genus not seen in the western mountains) are found at 8000, and the yew and Picea Webbiana at 10,000 ft. Pinus excelsa, which occurs in Bhutan, is absent in the wetter climate of Sikkim.

On the drier and higher mountains of the interior of the chain, the forests become more open, and are spread less uniformly over the hill-sides, a luxuriant herbaceous vegetation appears, and the number of shrubby Leguminosae, such as Desmodium and Indigofera, increases, as well as Ranunculaceae, Rosaceae, Umbelliferae, Labiatae, Gramineae, Cyperaceae and other European genera.

Passing to the westward, and viewing the flora of Kumaon, which province holds a central position on the chain, on the 80th meridian, we find that the gradual decrease of moisture and increase of high summer heat are accompanied by a marked change of the vegetation. The tropical forest is characterized by the trees of the hotter and drier parts of southern India, combined with a few of European type. Ferns are more rare, and the tree-ferns have disappeared. The species of palm are also reduced to two or three, and bamboos, though abundant, are confined to a few species.

The outer ranges of mountains are mainly covered with forests of Pinus longifolia, rhododendron, oak and Pieris. At Naini Tal cypress is abundant. The shrubby vegetation comprises Rosa, Rubus, Indigofera, Desmodium, Berberis, Boehmeria, Viburnum, Clematis, with an Arundinaria. Of herbaceous plants species of Ranunculus, Potentilla, Geranium, Thalictrum, Primula, Gentiana and many other European forms are common. In the less exposed localities, on northern slopes and sheltered valleys, the European forms become more numerous, and we find species of alder, birch, ash, elm, maple, holly, hornbeam, Pyrus, &c. At greater elevations in the interior, besides the above are met Corylus, the common walnut, found wild throughout the range, horse chestnut, yew, also Picea Webbiana, Pinus excelsa, Abies Smithiana, Cedrus Deodara (which tree does not grow spontaneously east of Kumaon), and several junipers. The denser forests are commonly found on the northern faces of the higher ranges, or in the deeper valleys, between 8000 and 10,500 ft. The woods on the outer ranges from 3000 up to 7000 ft. are more open, and consist mainly of evergreen trees.

The herbaceous vegetation does not differ greatly, generically, from that of the east, and many species of Primulaceae, Ranunculaceae, Cruciferae, Labiatae and Scrophulariaceae occur; balsams abound, also beautiful forms of Campanulaceae, Gentiana, Meconopsis, Saxifraga and many others.

Cultivation hardly extends above 7000 ft., except in the valleys behind the great snowy peaks, where a few fields of buckwheat and Tibetan barley are sown up to 11,000 or 12,000 ft. At the lower elevations rice, maize and millets are common, wheat and barley at a somewhat higher level, and buckwheat and amaranth usually on the poorer lands, or those recently reclaimed from forest. Besides these, most of the ordinary vegetables of the plains are reared, and potatoes have been introduced in the neighbourhood of all the British stations.

As we pass to the west the species of rhododendron, oak and Magnolia are much reduced in number as compared to the eastern region, and both the Malayan and Japanese forms are much less common. The herbaceous tropical and semi-tropical vegetation likewise by degrees disappears, the Scitamineae, epiphytal and terrestrial Orchideae, Araceae, Cyrtandraceae and Begoniae only occur in small numbers in Kumaon, and scarcely extend west of the Sutlej. In like manner several of the western forms suited to drier climates find their eastern limit in Kumaon. In Kashmir the plane and Lombardy poplar flourish, though hardly seen farther east, the cherry is cultivated in orchards, and the vegetation presents an eminently European cast. The alpine flora is slower in changing its character as we pass from east to west, but in Kashmir the vegetation of the higher mountains hardly differs from that of the mountains of Afghanistan, Persia and Siberia, even in species.

The total number of flowering plants inhabiting the range amounts probably to 5000 or 6000 species, among which may be reckoned several hundred common English plants chiefly from the temperate and alpine regions; and the characteristic of the flora as a whole is that it contains a general and tolerably complete illustration of almost all the chief natural families of all parts of the world, and has comparatively few distinctive features of its own.

The timber trees of the Himalaya are very numerous, but few of them are known to be of much value. The “Sál” is one of the most valuable of the trees; with the “Toon” and “Sissoo,” it grows in the outer ranges most accessible from the plains. The “Deodar” is also much used, but the other pines produce timber that is not durable. Bamboos grow everywhere along the outer ranges, and rattans to the eastward, and are largely exported for use in the plains of India.

Though one species of coffee is indigenous in the hotter Himalayan forests, the climate does not appear suitable for the growth of the plant which supplies the coffee of commerce. The cultivation of tea, however, is carried on successfully on a large scale, both in the east and west of the mountains. In the western Himalaya the cultivated variety of the tea plant of China succeeds well; on the east the indigenous tea of Assam, which is not specifically different, and is perhaps the original parent of the Chinese variety, is now almost everywhere preferred. The produce of the Chinese variety in the hot and wet climate of the eastern Himalaya, Assam and eastern Bengal is neither so abundant nor so highly flavoured as that of the indigenous plant.

The cultivation of the cinchona, several species of which have been introduced from South America and naturalized in the Sikkim Himalaya, promises to yield at a comparatively small cost an ample supply of the febrifuge extracted from its bark. At present the manufacture is almost wholly in the hands of the Government, and the drug prepared is all disposed of in India.

Zoology.—The general distribution of animal life is determined by much the same conditions that have controlled the vegetation. The connexion with Europe on the north-west, with China on the north-east, with Africa on the south-west, and with the Malayan region on the south-east is manifest; and the greater or less prevalence of the European and Eastern forms varies according to more western or eastern position on the chain. So far as is known these remarks will apply to the extinct as well as to the existing fauna. The Palaeozoic forms found in the Himalaya are very close to those of Europe, and in some cases identical. The Triassic fossils are still more closely allied, more than a third of the species being identical. Among the Jurassic Mollusca, also, are many species that are common in Europe. The Siwalik fossils contain 84 species of mammals of 45 genera, the whole bearing a marked resemblance to the Miocene fauna of Europe, but containing a larger number of genera still existing, especially of ruminants, and now held to be of Pliocene age.

The fauna of the Tibetan Himalaya is essentially European or rather that of the northern half of the old continent, which region has by zoologists been termed Palaearctic. Among the characteristic animals may be named the yak, from which is reared a cross breed with the ordinary horned cattle of India, many wild sheep, and two antelopes, as well as the musk-deer; several hares and some burrowing animals, including pikas (Lagomys) and two or three species of marmot; certain arctic forms of carnivora—fox, wolf, lynx, ounce, marten and ermine; also wild asses. Among birds are found bustard and species of sand-grouse and partridge; water-fowl in great variety, which breed on the lakes in summer and migrate to the plains of India in winter; the raven, hawks, eagles and owls, a magpie, and two kinds of chough; and many smaller birds of the passerine order, amongst which are several finches. Reptiles, as might be anticipated, are far from numerous, but a few lizards are found, belonging for the most part to types, such as Phrynocephalus, characteristic of the Central-Asiatic area. The fishes from the headwaters of the Indus also belong, for the most part, to Central-Asiatic types, with a small admixture of purely Himalayan forms. Amongst the former are several peculiar small-scaled carps, belonging to the genus Schizothorax and its allies.

The ranges of the Himalaya, from the border of Tibet to the plains, form a zoological region which is one of the richest of the world, particularly in respect to birds, to which the forest-clad mountains offer almost every range of temperature.

Only two or three forms of monkey enter the mountains, the langur, a species of Semnopithecus, ranging up to 12,000 ft. No lemurs occur, although a species is found in Assam, and another in southern India. Bats are numerous, but the species are for the most part not peculiar to the area; several European forms are found at the higher elevations. Moles, which are unknown in the Indian peninsula, abound in the forest regions of the eastern Himalayas at a moderate altitude, and shrews of several species are found almost everywhere; amongst them are two very remarkable forms of water-shrew, one of which, however, Nectogale, is probably Tibetan rather than Himalayan. Bears are common, and so are a marten, several weasels and otters, and cats of various kinds and sizes, from the little spotted Felis bengalensis, smaller than a domestic cat, to animals like the clouded leopard rivalling a leopard in size. Leopards are common, and the tiger wanders to a considerable elevation, but can hardly be considered a permanent inhabitant, except in the lower valleys. Civets, the mungoose (Herpestes), and toddy cats (Paradoxurus) are only found at the lower elevations. Wild dogs (Cyon) are common, but neither foxes nor wolves occur in the forest area. Besides these carnivora some very peculiar forms are found, the most remarkable of which is Aelurus, sometimes called the cat-bear, a type akin to the American racoon. Two other genera, Helictis, an aberrant badger, and linsang, an aberrant civet, are representatives of Malayan types. Amongst the rodents squirrels abound, and the so-called flying squirrels are represented by several species. Rats and mice swarm, both kinds and individuals being numerous, but few present much peculiarity, a bamboo rat (Rhizomys) from the base of the eastern Himalaya being perhaps most worthy of notice. Two or three species of vole (Arvicola) have been detected, and porcupines are common. The elephant is found in the outer forests as far as the Jumna, and the rhinoceros as far as the Sarda; the spread of both of these animals as far as the Indus and into the plains of India, far beyond their present limits, is authenticated by historical records; they have probably retreated before the advance of cultivation and fire-arms. Wild pigs are common in the lower ranges, and one peculiar species of pigmy-hog (Sus salvanius) of very small size inhabits the forests at the base of the mountains in Nepál and Sikim. Deer of several kinds are met with, but do not ascend very high on the hillsides, and belong exclusively to Indian forms. The musk deer keeps to the greater elevations. The chevrotains of India and the Malay countries are unrepresented. The gaur or wild ox is found at the base of the hills. Three very characteristic ruminants, having some affinities with goats, inhabit the Himalaya; these are the “serow” (Nemorhaedus), “goral” (Cemas) and “tahr” (Hemitragus), the last-named ranging to rather high elevations. Lastly, the pangolin (Manis) is represented by two species in the eastern Himalaya. A dolphin (Platanista) living in the Ganges ascends that river and its affluents to their issue from the mountains.

Almost all the orders of birds are well represented, and the marvellous variety of forms found in the eastern Himalaya is only rivalled in Central and South America. Eagles, vultures and other birds of prey are seen soaring high over the highest of the forest-clad ranges. Owls are numerous, and a small species, Glaucidium, is conspicuous, breaking the stillness of the night by its monotonous though musical cry of two notes. Several kinds of swifts and nightjars are found, and gorgeously-coloured trogons, bee-eaters, rollers, and beautiful kingfishers and barbets are common. Several large hornbills inhabit the highest trees in the forest. The parrots are restricted to parrakeets, of which there are several species, and a single small lory. The number of woodpeckers is very great and the variety of plumage remarkable, and the voice of the cuckoo, of which there are numerous species, resounds in the spring as in Europe. The number of passerine birds is immense. Amongst them the sun-birds resemble in appearance and almost rival in beauty the humming-birds of the New Continent. Creepers, nuthatches, shrikes, and their allied forms, flycatchers and swallows, thrushes, dippers and babblers (about fifty species), bulbuls and orioles, peculiar types of redstart, various sylviads, wrens, tits, crows, jays and magpies, weaver-birds, avadavats, sparrows, crossbills and many finches, including the exquisitely coloured rose-finches, may also be mentioned. The pigeons are represented by several wood-pigeons, doves and green pigeons. The gallinaceous birds include the peacock, which everywhere adorns the forest bordering on the plains, jungle fowl and several pheasants; partridges, of which the chikor may be named as most abundant, and snow-pheasants and partridges, found only at the greatest elevations. Waders and waterfowl are far less abundant, and those occurring are nearly all migratory forms which visit the peninsula of India—the only important exception being two kinds of solitary snipe and the red-billed curlew.

Of the reptiles found in these mountains many are peculiar. Some of the snakes of India are to be seen in the hotter regions, including the python and some of the venomous species, the cobra being found as high up as 8000 or 9000 ft., though not common. Lizards are numerous, and as well as frogs are found at all elevations from the plains to the upper Himalayan valleys, and even extend to Tibet.

The fishes found in the rivers of the Himalaya show the same general connexion with the three neighbouring regions, the Palaearctic, the African and the Malayan. Of the principal families, the Acanthopterygii, which are abundant in the hotter parts of India, hardly enter the mountains, two genera only being found, of which one is the peculiar amphibious genus Ophiocephalus. None of these fishes are found in Tibet. The Siluridae, or scaleless fishes, and the Cyprinidae, or carp and loach, form the bulk of the mountain fish, and the genera and species appear to be organized for a mountain-torrent life, being almost all furnished with suckers to enable them to maintain their positions in the rapid streams which they inhabit. A few Siluridae have been found in Tibet, but the carps constitute the larger part of the species. Many of the Himalayan forms are Indian fish which appear to go up to the higher streams to deposit their ova, and the Tibetan species as a rule are confined to the rivers on the table-land or to the streams at the greatest elevations, the characteristics of which are Tibetan rather than Himalayan. The Salmonidae are entirely absent from the waters of the Himalaya proper, of Tibet and of Turkestan east of the Terektag.

The Himalayan butterflies are very numerous and brilliant, for the most part belonging to groups that extend both into the Malayan and European regions, while African forms also appear. There are large and gorgeous species of Papilio, Nymphalidae, Morphidae and Danaidae, and the more favoured localities are described as being only second to South America in the display of this form of beauty and variety in insect life. Moths, also, of strange forms and of great size are common. The cicada’s song resounds among the woods in the autumn; flights of locusts frequently appear after the summer, and they are carried by the prevailing winds even among the glaciers and eternal snows. Ants, bees and wasps of many species, and flies and gnats abound, particularly during the summer rainy season, and at all elevations.

Mountain Scenery.—Much has been written about the impressiveness of Himalayan scenery. It is but lately, however, that any adequate conception of the magnitude and majesty of the most stupendous of the mountain groups which mass themselves about the upper tributaries and reaches of the Indus has been presented to us in the works of Sir F. Younghusband, Sir W. M. Conway, H. C. B. Tanner and D. Freshfield. It is not in comparison with the picturesque beauty of European Alpine scenery that the Himalaya appeals to the imagination, for amongst the hills of the outer Himalaya—the hills which are known to the majority of European residents and visitors—there is often a striking absence of those varied incidents and sharp contrasts which are essential to picturesqueness in mountain landscape. Too often the brown, barren, sun-scorched ridges are obscured in the yellow dust haze which drifts upwards from the plains; too often the whole perspective of hill and vale is blotted out in the grey mists that sweep in soft, resistless columns against these southern slopes, to be condensed and precipitated in ceaseless, monotonous rainfall. Few Europeans really see the Himalaya; fewer still are capable of translating their impressions into language which is neither exaggerated nor inadequate.

Some idea of the magnitude of Himalayan mountain construction—a magnitude which the eye totally fails to appreciate—may, however, be gathered from the following table of comparison of the absolute height of some peaks above sea-level with the actual amount of their slopes exposed to view:—

Relative Extent of Snow Slopes Visible.

| Name of Mountain. | Place of Observation. | Height above sea. | Amount of Slope exposed. |

| Everest | Dewanganj | 29,002 | 8,000 |

| Everest | Sandakphu | ” | 12,000 |

| K2 or Godwin-Austen | Between Gilgit and Gor, 16,000 ft. | 28,250 | |

| Pk. XIII. or Makalu | Purnea, 200 ft | 27,800 | 8,000 |

| Pk. XIII. or Makalu | Sandakphu, 12,000 ft. | ” | 9,000 |

| Nanga Parbat | Gor, 16,000 ft. | 26,656 | 23,000 |

| Tirach Mir | Between Gilgit and Chitral, 8000 ft. | 25,400 | 17-18,000 |

| Rakapushi | Chaprot (Gilgit), 13,000 ft. | 25,560 | 18,000 |

| Kinchinjunga | Darjeeling, 7000 ft. | 28,146 | 16,000 |

| Mont Blanc | Above Chamonix, 7000 ft. | 15,781 | 11,500 |

It will be observed from this table that it is not often that a greater slope of snow-covered mountain side is observable in the Himalaya than that which is afforded by the familiar view of Mont Blanc from Chamonix.

Authorities.—Drew, Jammu and Kashmir (London, 1875); G. W. Leitner, Dardistan (1887); J. Biddulph, Tribes of the Hindu Kush (Calcutta, 1880); H. H. Godwin-Austen, “Mountain Systems of the Himalaya,” vols. v. and vi. Proc. R. G. S. (1883-1884); C. Ujfalvy, Aus dem westlichen Himalaya (Leipzig, 1884); H. C. B. Tanner, “Our Present Knowledge of the Himalaya,” vol. xiii. Proc. R. G. S. (1891); R. D. Oldham, “The Evolution of Indian Geography,” vol. iii. Jour. R. G. S.; W. Lawrence, Kashmir (Oxford, 1895); Sir W. M. Conway, Climbing and Exploring in the Karakoram (London, 1898); F. Bullock Workman, In the Ice World of Himalaya (1900); F. B. and W. H. Workman, Ice-bound Heights of the Mustagh (1908); D. W. Freshfield, Round Kangchenjunga (1903).

For geology see R. Lydekker, “The Geology of Káshmir,” &c., Mem. Geol. Surv. India, vol. xxii. (1883); C. S. Middlemiss, “Physical Geology of the Sub-Himálaya of Gahrwal and Kumaon,” ibid., vol. xxiv. pt. 2 (1890); C. L. Griesbach, Geology of the Central Himálayas, vol. xxiii. (1891); R. D. Oldham, Manual of the Geology of India, chap. xviii. (2nd ed., 1893). Descriptions of the fossils, with some notes on stratigraphical questions, will be found in several of the volumes of the Palaeontologia Indica, published by the Geological Survey of India, Calcutta.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 11/17/2022 15:23:46 | 58 views

☰ Source: https://oldpedia.org/article/britannica11/Himalaya | License: Public domain in the USA. Project Gutenberg License

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF