Lübeck

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) Lübeck:

By: Gotthard Deutsch

Free city of Germany; situated on the River Trave, not far from the Baltic Sea; it forms, with the surrounding territory, a free state. In 1900 it had a population of 82,813, including 663 Jews. Like most of the free cities of Germany, Lübeck did not tolerate the Jews. In 1350 the city council wrote to Duke Otto of Brunswick-Lüneburg requesting him to exterminate the Jews living in his territory, as they were responsible for the plague, which would not cease until all Jews had been killed. As the council does not mention any order to this effect in the city, it is clear that Jews could not have lived there before then. In 1499 the local chronographer, Reimer Kock, states expressly that "there are no Jews in Lübeck, as they are not needed here." The Thirty Years' war and, perhaps, the Chmielnicki persecutions in Poland seem to have caused a number of Jews to go to Lübeck. The gild of the goldsmiths complained in 1658 that "many Jews and other suspicious characters sneak daily into the city to deal in precious metals"; and the council decreed, April 15, 1677, that no Jew should be permitted to stay in the city overṇight without the express permission of the senate, which was rarely given. In 1680 two "Schutzjuden" of the senate, Samuel Frank and Nathan Siemssens, are mentioned. But when the senate accepted Siemssen's son-in-law, Nathan Goldschmidt, as "Schutzjude," the citizens objected, and wherever he rented a house the neighbors protested to the senate. It was, perhaps, due to an intrigue that Goldschmidt was accused of having received stolen goods (Feb. 15, 1694); the trial dragged on for at least five years, and its result is not known. The gilds continued to demand of the council the expulsion of all Jews, and finally saw their wishes fulfilled (March 4, 1699). In spite of that victory of the gilds, Jews not only made brief visits to the city, but the council permitted, as early as 1701, one Jew to remain as "Schutzjude" in consideration of an annual payment of 300 marks courant ($84).

The great difficulties which stood in the way of prospective Jewish settlers in Lübeck suggested the evasion of the prohibition by a settlement in the neighboring territory of Denmark. A number of Jews, mostly Polish fugitives, settled in the village of Moisling as early as 1700, and, in spite of constant protests by the gilds, the council had to grant them, as Danish subjects, the right to enter the city, although under great restrictions. Desiring to obtain jurisdiction over the Jews in Moisling, the city of Lübeck acquired, in 1765, the estate whose owner had feudal rights over the inhabitants of that village; when, in 1806, the King of Denmark ceded the district that included Moisling, to Lübeck the Jews there became subjects of the latter city. But when Lübeck was annexed to France (Jan. 1, 1811) all discriminations ceased; the special taxes of the "Schutzjuden" were abolished, and many Jews of Moisling, as well as of other places, moved to Lübeck, where they at once purchased a lot for a synagogue. In the following years their numbers were rapidly augmented, especially in consequence of the expulsions during the siege of Hamburg. As soon, however, as the French domination had ceased, the senate began to debate the restriction of the Jews, to whom it proposed giving "an appropriate new constitution" (1815), while the gilds peremptorily demanded their expulsion. The Jews protested against this violation of their rights, and, together with the Jewish citizens of other free cities, appealed to the Congress of Vienna, engaging Carl August Buchholz as their advocate. But the citywould not yield, in spite of the intercession of the Prussian chancellor Prince Hardenberg and of the Austrian chancellor Prince Metternich.

Expelled After Congress of Vienna.The Congress of Vienna finally adopted Article 16 of the "Bundesakte," which guaranteed to the Jews in all German states the rights which they had obtained "from" the various states, instead of "in" the various states, as the original text read (June 8, 1815). Having thus obtained a free hand, the senate of Lübeck decreed (March 6, 1816) that all Jews should leave the city within four weeks. The Jews again protested, but finally were compelled to accept the proposition of the senate, which guaranteed to all Jews who would settle in Moisling the rights of Lübeck citizens, subject to certain limitations (Sept., 1821); in 1824 all Jews, with the exception of a few "Schutzjuden," had left the city. The senate now showed a certain amount of good-will toward its Jewish subjects by giving them a house in Moisling for their rabbi, and by building a new synagogue, for which the congregation was required to pay only a moderate annual rent.

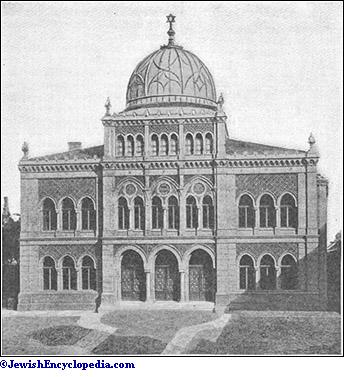

Since 1831 the Jews have had to serve in the militia; in 1837 a parochial school, subsidized by the city, was opened; and in 1839 the senate issued an order which compelled the gilds to register Jewish apprentices. A commission appointed in 1842 reported that the condition of the Jews should be improved by an extension of their rights, but their emancipation did not become perfect until the law of Oct. 9, 1848, abolished all their disabilities. In 1850 a new synagogue was acquired. This brought to the young congregation considerable annoyance; the ill-disposed neighbors, who claimed that the ritual bath connected with it spread an unbearable smell of garlic, endeavored to obtain an injunction against it (this building gave way to a new synagogue in 1880). In 1859 the rabbi moved from Moisling to Lübeck, and in the same year a parochial school was opened in the city. In 1869 the school in Moisling was closed, and in 1872 the Moisling synagogue, which had not been used for some time, was demolished. A law of Aug. 12, 1862, modified the form of oath ("More Judaico") which Jews until that time had been compelled to use, and introduced a new form, which remained in force until the German law of 1879, regulating civil procedure, abolished it.

The Lübeck congregation has a parochial school of three grades, and religious instruction for Jewish children attending public schools has been made compulsory by the law of Oct. 17, 1885. The city pays to the congregation an annual subsidy. The rabbis of the congregation have been: Akiba Wertheimer (called also Akiba Victor; up to 1816; d. 1835, as rabbi of Altona); Ephraim Joël, an uncle of Manuel and David Joël (1825-51); Süssmann Adler (teacher and preacher, 1849-51; rabbi, 1851-1869); S. Carlebach, the present (1904) incumbent (since 1869). The congregation has a number of educational, devotional, and social organizations.

- Jost, Neuere Gesch. der Israeliten, i. 32 et seq.;

- Grätz, Gesch. xi. 324 et seq.;

- Carlebach, Gesch. der Juden in Lübeck und Moisling, Lübeck, 1898;

- Statistisches Jahrbuch, 1903.

Categories: [Jewish encyclopedia 1906]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 09/04/2022 16:25:26 | 33 views

☰ Source: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/10165-lubeck.html | License: Public domain

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF