Byzantine Empire

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | Byzantine Empire | |

|---|---|

| |

| Justinian I ruled the empire at its peak in 527 to 565. He rebuilt Constantinople, including Hagia Sophia cathedral, reconquered Italy, and compiled the Code of Justinian. He was the last Latin-speaking emperor. | |

| Greek name | |

| Greek | Βασιλεία Ῥωμαίων |

| Romanization | Basileía Rhōmaíōn |

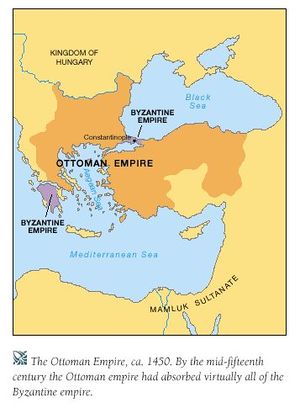

Constantine made Constantinople his capital in 330. When the empire split in 395, the city became the capital of Eastern Roman Empire. The Byzantine Empire was a continuation of the eastern empire. By the time of Heraclius (r. 610–641), the empire had lost its classical character and had emerged as a feudal state. Egypt, Syria, and the Holy Land were lost to the Arabs by 641, leaving only the Balkans, Anatolia, and North Africa. Heraclius changed the official language from Latin to Greek. He dealt with the disappearance of revenue and the loss of the recruiting areas by establishing "themes" that allowed lords to recruit peasant soldiers based on reciprocal obligations rather than money. North Africa was captured by the Arabs in the seventh century. Under the Macedonian dynasty (867-1025), Byzantium experienced a revival while western Europe was being ravaged by Vikings and Magyars. This second golden age ended in 1071 with a Seljuk victory at Manzikert. Constantinople was sacked by crusaders in 1204. The city was recaptured by Greek forces in 1261. It fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, ending the history of the empire.

Constantinople was built on the site of the Greek colony of Byzantium. The term "Byzantine" was not used when the empire was in existence. It was coined by historians of the 16th century to distinguish between the Latin-speaking classical empire and the Greek-speaking medieval state.

In the Dark Ages, Byzantine monks played a vital role in preserving classical civilization. They copied ancient learning, including the works of Aristotle, Plato, Archimedes, the Greek New Testament, and Roman law in the form of the Code of Justinian. In the 12th century, various classics became available to Latin readers as retranslations from Arabic. Beginning in the 13th century, Latin translators gained access to a wide range of original-language manuscripts from Byzantine sources.

Contents

- 1 Names

- 2 History

- 2.1 Justinian I (r. 527-565)

- 2.2 Dark Ages (550 to 843)

- 2.3 Macedonian dynasty (867-1025)

- 2.4 Manzikert (1071)

- 2.5 First Crusade (1096–1099)

- 2.6 Latin Empire (1204-1261)

- 2.7 Restoration (1261)

- 2.8 Andronicus II Palaiologos (r. 1282 – 1328)

- 2.9 Venice and Genoa

- 2.10 Coinage

- 2.11 Disintegration (1340-1453)

- 2.12 Fall (1453)

- 3 Art

- 4 Education

- 5 Religion

- 6 See also

- 7 Further reading

- 8 References

- 9 External links

Names[edit]

The inhabitants of the empire referred to themselves as "Romans" and to their religion as "Roman Orthodox." In the West, they were called "Greeks" and their leader was the "emperor of Constantinople." To medieval historian William of Tyre, the Byzantine emperors were Latin until 800 and Greek after that. That is to say, Constantinople had lost its imperial legitimacy when Charlemagne was crowned by the pope.[2]

Renaissance usage[edit]

Renaissance historians were less interested in which emperor was legitimate. They developed the idea of dividing history into three parts: ancient (before 500), medieval (500-1500), and modern (since 1500).[3] German historian Hieronymus Wolf applied the term "Byzantine" to the medieval Greek state in his book Corpus Historiæ Byzantinæ (1557).[4] This word is derived from "Byzantium," an alternative name for Constantinople. It emphasizes the change in culture that occurred as the Latin-speaking classical Eastern Roman Empire evolved into a Greek-speaking medieval Orthodox Christian state.

The English word "byzantine"[edit]

The word "byzantine" is defined in various dictionaries as meaning "complex and difficult to understand." This usage is first recorded in 1937.[5] It is based on the complex politics of Justinian's court as recorded by the historian Procopius. Procopius was secretary to Belisarius, Justinian's best-known commander. Procopius found it baffling that Justinian would prefer Narsus, a commander of inferior ability, to Belisarius. This preference can be explained by the fact that Narsus was a eunuch and thus not a threat to the dynasty. Belisarius is often rated as one of history's great military leaders.

History[edit]

Events during the Crisis of the Third Century suggested that the legions on the Danube and those on the Rhine required separate emperors to prevent the outbreak of revolts. In 285, Diocletian divided his realm into four administrative units. A series of unifications and redivisions followed. Constantine built "New Rome," later Constantinople, as his capital in 330. The division between East and West became final upon the death of Theodosius I in 395. In 413, Theodosius II built an enormous wall for city. The West fell to barbarian invasion in 476, but the eastern empire continued until 1453.

The East survived the fall of the western empire largely because of its greater financial resources. Despite a shortage of manpower, Byzantium could generally pay off the armies that threatened its security. In 500, the empire retained a city-based classical civilization. By the end of the sixth century, the public urban spaces central to classical culture were in decay. Public culture survived only in the churches, and icons became a focus of great reverence.[6]

Justinian I (r. 527-565)[edit]

The Nika revolt and Hagia Sophia[edit]

Constantinople's unruly sports fans, called demes, normally fought only each other. The greens and blues supported rival chariot racing teams at the city's hippodrome. They could be paid to act in concert by unscrupulous politicians. Justinian deployed the army against the demes during the Nika riots in 532. Some 30,000 were killed and the palace area was burned down.[7] With his capital in ruins, Justinian energetically rebuilt, erecting the magnificent Hagia Sophia.

Code of Justinian[edit]

Roman law was notoriously complex and disorganized. Justinian appointed a committee of lawyers headed by Tribonian to produce a compilation and summary, now called the Code of Justinian. The first section, called Codex Constitutionum, was published in 529.[8] This is a collection of the decrees and rulings of classical Rome. The Institutiones, a textbook for first year law students, followed in 533. The opinions of various jurists were extracted to create the Digesta, which was published 534. The modern edition of the full code is a three volume work of nearly 2,400 pages.[9]

The imperial law school in Beirut was destroyed by an earthquake and tsunami in 551 and not rebuilt. Greek judges without university training had little use for Justinian's complex Latin code. In the 12th century, the code was revived and taught to students in Bologna and in other schools in the West. It would remain the benchmark of European law until the Napoleonic Code was issued in the 19th century.

Plague and finances[edit]

A series of volcanic eruptions made 536 to 545 the coldest decade in the last two thousand years. An eruption in Iceland in 536 created a ‘dust-veil event.’ The historian Procopius described this event: "During this year a most dread portent took place. For the sun gave forth its light without brightness ... and it seemed exceedingly like the sun in eclipse, for the beams it shed were not clear."[10]

Rigorous collection by John the Cappadocian helped increase revenue to an all-time peak of 11.3 million solidi, or 51 tons of gold, in 540. In 541, the Goths, Bulgars, and Persians began simultaneous offensives against the empire. The plague arrived in Constantinople in 542. It killed 250,000 in this city alone, over half the population. Victims were typically dead within two or three days. Despite John's reforms, as well as an expansion of territory, revenue for 555 was only 6 million solidi, no better than when Justinian came to the throne. This suggests that the plague led to long-term depopulation.[11]

Although Procopius accused Justinian of debasing the coinage, testing has determined that gold coins of his reign are 98.5 percent fine. To deal with the crisis of the 540s, Peter Barysmes, Justinian's chief of finances, minted "light-weight solidi" of 3.8 to 4.37 grams rather than the full weight of 4.56 grams. The light-weight solidi were marked as such. It is unknown what inflationary effect they might have had.[12]

Dark Ages (550 to 843)[edit]

The military setbacks under Justin II (r. 565–574), Justinian's nephew and successor, suggest that Justinian had overstretched empire's resources. Italy, conquered at great cost from the Ostrogoths, was overrun in 568-572 by the Lombards. This invasion was largely unopposed. The Avars raided across the Danube in 573 or 574 and the fortress of Dara, gateway to Anatolia, fell to the Persians in 573. Slav migration into the Balkans began in 581 and continued for the next century.

Phocas[edit]

An army rebellion in 602 put Phocas, a centurion, on the throne. His strictly orthodox religious policies provoked a rebellion in monophysite Egypt in 608. Troops were pulled away from the east and the Persians overran the frontier fortifications of Merdin, Dara, Amida, and Edessa. A general collapse followed. Egypt had been the empire's principal source of revenue and grain. The loss of Egypt and Syria sent state revenues plummeting from 8.5 million solidi in 565 to 3.7 million solidi in 641.[11] Traditional history remembers Phocas as a villain and a usurper. "The hippodrome, the sacred asylum of the pleasures and the liberty of the Romans, was polluted with heads and limbs, and mangled bodies," according to Edward Gibbon. Phocas was, "the worthy rival of the Caligulas and Domitians of the first age of the empire."[13]

Heraclius[edit]

Heraclius (r. 610 to 641) executed Phocas, defeated the Sassanid Persians, and is credited with saving the empire. But the money-based economy proved impossible to revive. Instead, Heraclius established feudal lordships called themes to recruit soldiers. The Arabs defeated Heraclius in a decisive battle at Yarmouk in 636. Antioch and Jerusalem fell the following year. A demoralized Egypt fell to an Arab force led by 'Amr ibn al-'As of only 4,000 in 641.

Iconoclasm[edit]

Images of Jesus were approved by the Quinisext Council in 692. In 695, Justinian II (r. 685–711) put such an image on his coins. In reaction to these moves, a movement called iconoclasm, or image breaking, emerged. Greek-speakers tended to be more respectful of icons. The poorer non-Greeks of the East were more likely to be iconoclastic, perhaps influenced by Muslim views. The pro-icon faction was discredited as the Arabs advanced. The low point for the empire came in 718 with the second Arab siege of Constantinople. The Arabs were beaten back with Greek fire, the medieval version of napalm. The success of the Greek army in restoring the empire after the Arab siege led to the rise of iconoclastic commanders. Emperor Leo III issued a decree against icons in 730. The victories of Constantine V (r. 741–775) convinced many that image-breaking was sanctioned by God. Empress Irene restored the status of the icons in 787. Military reversals led Leo V to ban them again in 815. The controversy was finally resolved in 843 when the icons were restored to imperial favor.

Macedonian dynasty (867-1025)[edit]

The Macedonian dynasty, founded by Basil I in 867, was a golden age for Byzantium. Basil replaced the Code of Justinian with a Greek legal code called the Basilica. The military revival of this period did not prevent Sicily from falling to the Arabs in 902 or the sack of Thessalonica in 904. After 150 years of Arab terror on the seas, the Byzantines regained naval supremacy after a victory in 961. There was also was a revival of literature, including the Suda, an early encyclopedia, as well as the Lexicon and the Bibliotheca of Photius. After the devastation of the Dark Ages, Byzantine scholars devoted themselves to the project of carefully classifying, copying, preserving, and summarizing the learning that survived. This revival occurred while the West was suffering the ravages of the Viking and a relapse into its own Dark Ages. Basil II (r. 976–1025) stabilized the empire and retook territory in the Balkans and southern Italy. Revenue peaked in 1025 at 5.9 million soldi, the highest level since the Arab conquests in the seventh century.[14]

Manzikert (1071)[edit]

Treachery led to a defeat by Seljuks led by Alp-Arslan at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. Even more serious than the military aspect of the battle was that the emperor was captured by the Seljuks. This triggered a civil war that lasted from 1071 to 1081 and allowed the Turks to advance into Anatolia unopposed. The empire turned to mercenaries to make up for the loss of manpower.[15] After the Norman Conquest of 1066, much of the English nobility fled to Constantinople to join the Varangian Guard.

In the hope of obtaining naval assistance, the empire concluded a treaty with Venice in 1082. The treaty gave the Venetians a settlement in Constantinople and a tax free status that would eventually give Venice control of imperial trade. The Turkish threat eased in 1092 when Seljuk lands were divided among the sultan's many sons.

First Crusade (1096–1099)[edit]

With the Seljuks divided but still occupying the empire's Anatolian heartland, Emperor Alexios Komnenos plotted a comeback. In 1095, he sent a delegation to Italy to request the assistance of Pope Urban II. Although Alexios had merely requested mercenaries, the pope decided to go one better and declared a crusade to free the Holy Land. There was an enormous response to Urban's call across Western Europe. The First Crusade (1096–1099) succeeded in recapturing the Holy Land for Christianity.

With the help of the Crusaders, the Byzantines regained Nicene and other territory. The Crusader states remained in the Holy Land for two centuries. They diverted Muslim attention away from Constantinople and allowed the empire to revive under Manuel I Komnenos.

Manual expelled the tax-exempt Venetians in 1171. He attempted to reconquer central Anatola, but was defeated by the Seljuks at Myriokephalon in 1176. Manuel favored the Genoese and the crusader kingdoms. These policies inspired anti-Latin riots and were reversed after he died in 1180. A period of chaotic administration followed. The last emperor of the Komnenos dynasty was lynched in a popular uprising in 1185.

Latin Empire (1204-1261)[edit]

In 1198, Pope Innocent III proposed a Fourth Crusade to conquer Muslim Egypt and use this country as a base to recapture Jerusalem. For Venice, the Egyptians were partners in trade while the Byzantines were allies of the hated Genoese. The Venetians offered transportation, but demanded that the crusaders repay debts with money from the Byzantines. The Crusaders laid siege to Constantinople in June 1203. Most crusaders were reluctant to fight fellow Christians and continued to Acre as soon as transportation could be arranged. But others remained and pressed on with the siege. In February 1204, Constantinople was sacked, to the horror of Christians East and West. This was the first time that the Byzantine capital was taken. The crusaders set up a Latin Empire, so called as it promoted the use of Latin. The area that remained under Greek control was partitioned among the Empire of Nicaea, the Empire of Trebizond, and the Despotate of Epirus. The Latin Empire lasted until Nicaea captured Constantinople in 1261.Restoration (1261)[edit]

The Byzantines made a strong recovery under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1261–1282), who ousted the Latins. Michael agreed to unite the Orthodox and Catholics churches in the Union of Lyon in 1272. The union was successful in preventing a crusade against Constantinople. In religious terms, few clerics in either the East or in the West accepted its validity. The Byzantine revival was cut short by a Greek manpower shortage. There were far more Turkish warriors. The Byzantines did what they could to counter this advantage by paying Turks to fight each other. Nonetheless, the Turks were plundering Anatolia at will by 1280. Michael remained focused on Charles of Anjou in Sicily, who was threatening to invade. The Sicilian Vespers of 1282, an Italian rebellion funded by the Byzantines, defused the French threat.

Andronicus II Palaiologos (r. 1282 – 1328)[edit]

Michael's son Andronicus II Palaiologos (r. 1282–1328) tried to save money by dismissing the regular army and navy in favor of a mercenary-only military. This move allowed the emperor to lower taxes. Mercenaries were also less likely to try to overthrow the emperor. Although the Byzantines had much experience with mercenaries, they had always placed them alongside imperial soldiers to discourage defection. In 1302, the Ottoman Turks defeated the Byzantines at Bapheus. The Greeks were pushed out of Anatolia and the empire was reduced to a minor state.

Venice and Genoa[edit]

Customs revenue had long been the empire's main source of income. The Byzantines concluded the Treaty of Nymphaeum with the Genoese in 1261. This treaty was similar to Constantinople's earlier treaty with the Venetians. It gave Genoese citizens a tax exempt status and a settlement in Galata, across the Golden Horn from Constantinople. In exchange, the Genoese were to provide naval assistance to the Byzantines. Command of the Genoese fleet was later divided, making the city an ineffectual ally. The Byzantine responded by cancelling the treaty.

In 1285, Andronicus dismantled the Byzantine fleet and hired the Genoese again. The Genoese proved to be less interested in fighting the empire's enemies than in gaining control of its trade. Without a wall to protect it, Galata was burned by the Venetians in 1296.[16] In 1303, the emperor granted the Genoese the right to build a small wall around Galata. The Genoese built larger fortifications than the treaty allowed, making Galata a state within a state. The town's defenses were upgraded in 1348 when Galata Tower was completed. It soon overshadowed Constantinople as a trading center.

Coinage[edit]

Venice began issuing a gold coin called the ducat in 1284. Andronicus repeatedly debased the hyperpyron, a gold coin which had replaced the solidus in 1092. Byzantine coinmaking skill declined in the 1300s and the amount of gold in each coin became less uniform. Merchants switched to the Venetian coin, which became standard in Mediterranean trade. Constantinople stopped issuing gold coins around 1350.

Disintegration (1340-1453)[edit]

In 1340, Byzantium had a territory roughly equivalent to that of modern Greece. Both the Serbs and the Ottomans took advantage of a civil war in 1341–1347 to expand their territory. By the time this conflict was resolved, the empire was reduced to Constantinople and a few nearby towns. Empress Anna pawned the crowned jewels to Venice in 1343 for 30,000 ducats.[17] The Black Death killed a third of the population in 1347–1349. The Black Death hit cities across Europe and the Middle East, but Constantinople's recovery was particularly slow.[18]

The Ottomans captured Gallipoli in 1354, giving them a foothold in Europe. In 1369, the Ottomans captured Adrianople, the empire's third largest city. The Byzantines were left in a militarily untenable position. John went to Rome and declared himself Catholic in a last ditch appeal for aid. In 1371, he recognized Ottoman supremacy. In 1373, John blinded his own son Andronicus to please the sultan.[18] Timur defeated the Ottomans at the battle of Ankara in 1402, giving the Byzantines an unexpected reprieve.

Fall (1453)[edit]

On May 29, 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottomans led by Mehmet II after a long cannon bombardment. The conquering Turks stormed through a city full of empty neighborhoods. These had been abandoned after the Black Death more than a century earlier. The relatives of the last Byzantine emperor continued to rule Morea for a few years before being absorbed by the Ottoman Empire in 1460, ending the Palaiologos dynasty. The Ottomans moved their capital from Adrianople to Constantinople.

Art[edit]

In the fifth and sixth centuries, Constantinople developed a distinctive architecture. Large domes such as Hagia Sophia were built on pendentives over a square. Marble veneering was applied as well as colored mosaics and gold backgrounds. The 550 to 843 period was a Dark Age. Very little art from this period survived. The numerous icons produced were later destroyed by the Iconoclasts.[19]The Middle Byzantine period, or Macedonian Renaissance, began in 843 and continued until 1204. The defeat of the Iconoclasts allowed for a flowering of Orthodox art. Notable artwork of this period includes the richly illustrated Paris Psalter and the Limburg staurotheke (relic container). Many artists were employed illustrating church walls, although little of this type of art survived the Muslim conquest. The best known example is the illustrations of various imperial families in the South Gallery of Hagia Sophia. These portraits have given Byzantine art a reputation for stern remoteness. But Byzantine artists could also evoke strong emotion, for example with a painting of the lamentation in the Church of St. Panteleimon in Nerezi, Macedonia (1164).[19]

The Late Byzantine period dates from 1261 to 1453. This period focused on reconstruction, including the redecoration of Chora Church (1321).[19]

Education[edit]

Classical education[edit]

In classical times, the core secondary curriculum was Homer, Euripides, Aristophanes, and Demosthenes. Those who continued with their studies could go on to Herodotus, Thucydides, Plato, and Aristotle. The academies of Athens and Alexandria were the best-known centers of education. In the fifth century, Christian schools were established in Gaza and Constantinople. In 529, Justinian banned pagans from teaching and closed the academies. Simplicius of Cilicia (c. 490 – c. 560) was empire's last notable pagan writer. He fled to Persia with a group of seven philosophers. After 600, writing by pagan authors disappeared and Christian culture became dominant.[20]

Starting in the sixth century, fewer and fewer writers used classical language or literary style. Medieval Greeks wrote as they spoke. The rise of vernacular represents a decline of classical education as opposed to any increase in literacy. In place of the classical list of authors, educated Greek Christians read the Bible and the Cappadocian fathers. A great deal of the writing that survived from the early medieval period focused on theological issues of little interest today, including the monophysite heresy.[20]

High Middle Ages[edit]

Education revived in the eleventh century. The University of Constantinople, founded in 1045, trained imperial bureaucrats. The law school was headed by John Xiphilinus and a school of philosophy was headed by Michael Psellus. Psellus reintroduced Homer, Plato and other classics into the curriculum. Emperor Michael VII Ducas (r. 1071–78) was his best-known student. Anna Comnena, daughter of Emperor Alexios, wrote a history in fine classical style in the 12th century.

Transmission of Greek learning to the West[edit]

In the West, Greek was forgotten during the Dark Ages. Aside from the works of Boethius and Cassiodorus, almost all classical learning was lost. Charlesmagne's palace in Aachen was one of the few places in Dark Age Europe which could boast a classical encyclopedia. If the illiterate Charlemagne had a question about astronomy or the natural world, he'd have Alcuin of York look it up in Natural History by Pliny the Elder.[21]

The Abbasid (Persian) caliphs sponsored Arabic translation of works in Greek, Syriac, and Persian at the House of Wisdom in Baghdad. When the Kingdom of Castile captured Toledo in 1085, a large Muslim library fell into Christian hands. A school was founded to translate and distribute these works. Italian Gerald of Cremona traveled to Toledo in 1167 and translated 87 books from Arabic to Latin. By 1200, the intellectually critical classical authors had been translated, aside from Plato. Gerald translated Aristotle, Euclid, Ptolemy, and Archimedes while Mark of Toledo translated Galen (as well as the Koran). These translations were taught at the newly founded universities and were the basis of the 12th Renaissance.

William of Moerbeke[edit]

The need to rely on retranslations from Arabic left Europe hungry for direct translations from Greek. The Crusades put many Latins in contact with Byzantium and gave them access to Greek versions of the classics. William of Moerbeke (d. 1286), a Flemish Dominican, went to Nicene in 1260 and acquired a large collection of manuscripts. He was later appointed the Latin Archbishop of Corinth under the provisions of the Union of Lyons. William translated works of Aristotle, Archimedes, Hero, Galen, and Proklos.[22] Aristotle was the classical world's ultimate authority on a wide range of subjects and William played a major role in his "rediscovery."

Maximus Planudes[edit]

A Greek version of Almagest by Ptolemy was discovered by Byzantine scholar Maximus Planudes in the 1290s. Planudes was a rare Byzantine who was proficient in Latin. Planudes and others drew maps following the descriptions given by Ptolemy. These maps made the publication of Almagest in Italy in 1477 a major event. In Columbus's day, this book was the authority on geography and astronomy.

Renaissance[edit]

In the Renaissance, a wide range of works were translated from Byzantine manuscripts. Constantinople's decline and fall after 1350 meant that there were both Greeks fleeing the city and buyers in the West anxious to preserve manuscripts. Cardinal Bessarion collected over a thousand Greek texts and donated them to the Republic of Venice in 1468, including Venetus A, a well-known manuscript of the Iliad. This became the basis for the Marciana Library.

Religion[edit]

The early church was led by the bishops of the three apostolic sees, Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch. After Christianity was legalized by Constantine in 313, there was a series of ecumenical councils called by various emperors to settle disputes.

Council of Chalcedon[edit]

In 451, the Council of Chalcedon designated five bishops as patriarchs. These were the bishops of the apostolic sees as well as those of Constantinople and Jerusalem. At this time, the western empire was disintegrating. The city of Rome had fallen to the Goths in 410 and would fall to the Vandals in 455. The Eastern Roman Empire, with its capital in Constantinople, would remain powerful and prosperous for the next century.

The council ruled that Christ had a dual human-divine nature. There was a bitter struggle between the orthodox, who accepted this conclusion, and the monophysites, who rejected it. This struggle inspired Justinian to take full control of the eastern church. He decreed that the five patriarchs were a decision-making body for the church, called the pentarchy. Justinian's policy of imperial control was resisted by Rome, but continued by subsequent emperors.

Orthodox cannon law[edit]

In 638–640, the Arabs overran Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria, leaving only the sees of Constantinople and Rome in Christian hands. Greek speakers looked to Constantinople for leadership while Latin speakers looked to Rome. The Quinisext Council of 692 allowed for married clergy and established the foundation for a separate Orthodox cannon law. Although Greek-speaking clerics dominated the "Byzantine papacy" of 537 to 752, the emperor could not get the pope to agree to the cannons of this council.

Schism with Rome[edit]

The donations of Pepin in 754 and 756 gave the bishop of Rome control in central Italy. Political independence allowed the popes to assert a claim of supremacy over the whole church.

Constantinople rejected papal supremacy in the Photian schism of 863–867. An agreement to resolve the schism was made between the Pope John VIII and Patriarch Photius. Photius produced a Greek translation of the agreement that was inconsistent with the Latin version on several points. The papal legates didn't press the issue as the pope needed the help of the Byzantine navy to fight Arab pirates at this time. The superficially resolved schism divided Christianity into two branches, an Orthodox, or Greek-speaking, church based in Constantinople and a Catholic, or Latin-speaking, church based in Rome. The excommunications of 1054 are sometimes described as the decisive event. However, the "Great Schism" of 1054 did little more than confirm the result of the Photian schism. Byzantine chroniclers of the time did not bother to record the event.

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Browning, Robert. The Byzantine Empire (1992)

- Brownworth, Lars. Lost to the West: The Forgotten Byzantine Empire That Rescued Western Civilization, (2009) 352 pages.

- Hussey, J. M. The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire (1990)

- Luttwak, Edward N. The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire (2009), military and diplomacy

- Shepard, Jonathan, ed. The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c.500-1492 (2009), advanced scholarship

- Theophanes. The Chronicle of Theophanes. Anni Mundi 6095-6305 (A.D.602-813) Ed. and trans. Turtledove H.(1982) University of Pennsylvania Press.

References[edit]

- ↑ Shepard, Jonathan, The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c.500-1492 (2019), p. 26. The replacement of the Western Empire by barbarian states posed, "new problems yet also diplomatic and strategic openings for the rulers of Constantinople...and this goes some way towards justifying the starting-point of this book around AD 500."

- ↑ Spoljarić, Luka, "William of Tyre and the Byzantine Empire: The Construction and Deconstruction of an Image," Central European University, Budapest, May 2008.

- ↑ "Middle Ages," Merriam-Webster

- ↑ Webb, Eugene, In Search of the Triune God: The Christian Paths of East and West, p. 354.

- ↑ Etymology Online, "Byzantine (adj.)"

- ↑ Shepard, pp. 128-129.

- ↑ Shepard, p. 120.

- ↑ Frier, Bruce W. (Editor), and Blume, Fred H., The Codex of Justinian: A New Annotated Translation, with Parallel Latin and Greek Text, Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- ↑ Corpus Iuris Civilis (Latin Edition). Lawbook Exchange Ltd; Reprint edition (November 1, 2010), ISBN 978-1584779780.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann, "Why 536 was ‘the worst year to be alive’, Science, Nov. 15, 2018.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Treadgold, W., A History of the Byzantine State and Society, 1997, p. 277.

- ↑ Harl, Dr. Kenneth W., "Early Medieval and Byzantine Civilization: Constantine to Crusades."

- ↑ Gibbon, Edward, The History Of The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire, "Chapter XLVI: Troubles In Persia.—Part III."

- ↑ Treadgold, W., p. 575.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Military History, Dupuy & Dupuy, 1979.

- ↑ "Catholic monument against Orthodox population", Hurriyet Daily News, August 29, 2020.

- ↑ The Venetians kept this crown until the French under Napoleon captured the city in 1797. Then it disappeared, presumably melted down.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Treadwell, pp. 760-783.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Jones, L.A., "Byzantine art", New Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Treadgold, W., pp. 264-267.

- ↑ Conte, Gian Biagio, Latin Literature: A History, p. 502, 1994.

- ↑ Kazhdan, A. "William of Moerbeke," Oxford Dictionary of the Byzantium., p. 2197, 1991.

External links[edit]

- Livius (April 28, 2011). Byzantine Empire. Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

Categories: [European History] [Roman Empire] [Medieval History] [Ottoman Empire] [Byzantine Empire]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/03/2023 11:11:53 | 179 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Byzantine_Empire | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF