Cornelius Vanderbilt

From Nwe

From Nwe

| Cornelius Vanderbilt | |

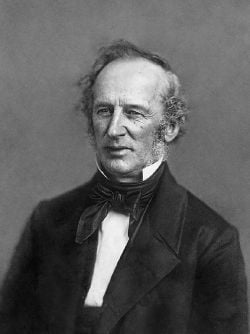

Vanderbilt c. 1844–1860

|

|

| Born | May 27, 1794 Staten Island, New York, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | January 4 1877 (aged 82) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Businessman |

| Spouse(s) | Sophia Johnson (m. 1813; died 1868) Frank Armstrong Crawford (m. 1869) |

| Children | 13 |

| Relatives | Vanderbilt family |

| Signature | |

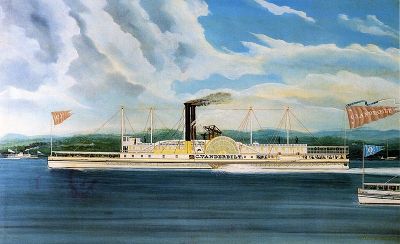

Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), American industrialist, born on Staten Island, New York. He entered the transportation business at the age of 16 when he established a freight-and-passenger ferry service between Staten Island and Manhattan. He owned a fleet of schooners during the War of 1812, entered the steamer business in 1818, and bought his first steamship in 1829. Rapidly expanding his operations, he became a vigorous competitor, reducing his rates and simultaneously improving his ships. Vanderbilt soon controlled much of the Hudson River trade; when his rivals paid him to take his traffic elsewhere, he set up routes from Long Island Sound to Providence, Rhode Island, and Boston.

Ruthless in business, Cornelius Vanderbilt was said by some to have made few friends in his lifetime but many enemies. His public perception was that of a vulgar, mean-spirited man who made life miserable for everyone around him, including his family. In his will, he disowned all his sons except for William, who was as ruthless in business as his father and the one Cornelius believed capable of maintaining the business empire.

At the time of his death, Cornelius Vanderbilt's fortune was estimated at more than $100 million. Yet, Vanderbilt lived in a modest home; it was his descendants who built the the great Gilded-Age mansions that bear his name. He gave to charitable causes, including funding for what would become Vanderbilt University.

Life

Vanderbilt was the fourth of nine children born in Port Richmond, on Staten Island in New York City to Cornelius Vanderbilt and Phebe Hand, a family of modest means. He stopped going to school at age 11. At age 13, he helped his father with the shipping around the New York Harbor.

His great-great-great-grandfather, Jan Aertson, was a Dutch farmer from the village of De Bilt in Utrecht, the Netherlands, who emigrated to New York as an indentured servant in 1650. The Dutch "van der" was eventually added to Aertson's village name to create "van der bilt," which was eventually condensed to Vanderbilt.[1] Most of Vanderbilt's ancestry was English, with his last ancestor of Dutch origin being Jacob Vanderbilt, his grandfather.

On December 19, 1813, Cornelius Vanderbilt married his cousin and neighbor, Sophia Johnson, daughter of his mother's sister. He and his wife had 13 children, one of which, a boy, died young.

After the death of his wife, Sophia, in 1868, Vanderbilt went to Canada where, on August 21, 1869, he married a cousin from Mobile, Alabama, Frank Armstrong Crawford. Ms. Crawford's mother was a sister to Phebe Hand Vanderbilt and to Elizabeth Hand Johnson. Ms. Crawford was 43 years younger than Vanderbilt. It was her nephew who convinced Cornelius Vanderbilt to commit funding for what would become Vanderbilt University. He also paid $50,000 for a church for his second wife's congregation, the Church of the Strangers. In addition, he donated to churches around New York, including a gift to the Moravian Church on Staten Island of 8+1⁄2 acres (3 hectares) for a cemetery (the Moravian Cemetery). He chose to be buried there.

Cornelius Vanderbilt died on January 4, 1877, at his residence, No. 10 Washington Place, after having been confined to his rooms for about eight months. The immediate cause of his death was exhaustion, brought on by long suffering from a complication of chronic disorders.[2] At the time of his death, aged 82, Vanderbilt had an estimated worth of $105 million.[3]

Ferry empire

During the War of 1812, he received a government contract to supply the forts around New York City. He operated sailing schooners, which is where he gained his nickname of "commodore."

In 1818, he turned his attention to steamships. The New York legislature had granted Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston a 30-year legal monopoly on steamboat traffic. Which means competition was forbidden by law. Working for Thomas Gibbons, Vanderbilt undercut the prices charged by Fulton and Livingston for service between New Brunswick, New Jersey, and Manhattan—an important link in trade between New York and Philadelphia. He avoided capture by those who sought to arrest him and impound the ship. Livingston and Fulton offered Vanderbilt a lucrative job piloting their steamboat, but Vanderbilt rejected the offer. He said "I don't care half so much about making money as I do about making my point, and coming out ahead." For Vanderbilt, the point was the superiority of free competition and the evil of government-granted monopoly. Livingston and Fulton sued, and the case went before the United States Supreme Court and ultimately broke the Fulton-Livingston monopoly on trade.

In 1829, he struck out on his own to provide steam service on the Hudson River between Manhattan and Albany, New York. By the 1840s, he had 100 steamships plying the Hudson and was reputed to have the most employees of any business in the United States.

During the 1849 California Gold Rush, he offered a shortcut via Nicaragua to California thus cutting 600 miles (960 km) at half the price of the Isthmus of Panama shortcut.

Rail empire

Early rail interest

Vanderbilt's involvement with early railroad development led him into being involved in one of America's earliest rail accidents. On November 11, 1833, he was a passenger on a Camden & Amboy train that derailed in the meadows near Hightstown, New Jersey when a coach car axle broke because of a hot journal box. He spent a month recovering from injuries that included two cracked ribs and a punctured lung. Uninjured in this accident was former President of the United States John Quincy Adams, riding in the car ahead of the one that derailed.

In 1844, Vanderbilt was elected as a director of the Long Island Rail Road, which at the time provided a route between Boston and New York City via a steamboat transfer. In 1857, he became a director of the New York and Harlem Railroad.

New York Central Railroad

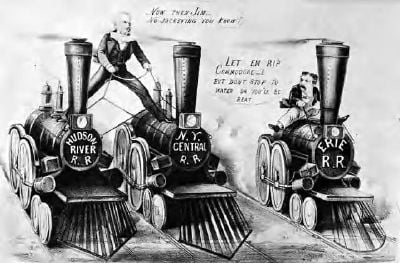

In the early 1860s, Vanderbilt started withdrawing capital from steamships and investing in railroads. He acquired the New York and Harlem Railroad in 1862-1863, the Hudson River Railroad in 1864, and the New York Central Railroad in 1867. In 1869, they were merged into New York Central and Hudson River Railroad.

Grand Central Depot

In October 1871, Vanderbilt struck up a partnership with the New York and New Haven Railroad to join with the railroads he owned to consolidate operations at one terminal at West 42nd Street called Grand Central Depot, which was the original Grand Central Terminal, where his statue reigns today. The glass roof of the depot collapsed during a blizzard on the same day Vanderbilt died in 1877. The station was not replaced until 1903-1913.

Rivalry with Jay Gould

By 1873, he had extended the lines to Chicago, Illinois. Around this time Vanderbilt tried to gain control of the Erie Railroad, which brought him into direct conflict with Jay Gould, who was then in control of the Erie. Gould won the battle for control of the railroad by "watering down" its stock, which Vanderbilt bought in large amounts. Vanderbilt lost more than $7 million in his attempt to gain control, although Gould later returned most of the money. Vanderbilt was very accustomed to getting what he wanted, but it seems that he met his match in Jay Gould. Vanderbilt would later say of his loss "never kick a skunk." In fact, this was not the last time that Gould would serve to challenge a Vanderbilt. Years after his father's death, William Vanderbilt gained control of the Western Union Telegraph company. Jay Gould then started the American Telegraph Company and nearly forced Western Union out of business. William Vanderbilt then had no choice but to buy out Gould, who made a large profit from the sale.

Legacy

Ruthless in business, Cornelius Vanderbilt was said by some to have made few friends in his lifetime but many enemies. His public perception was that of a vulgar, mean-spirited man who made life miserable for everyone around him, including his family. He often said that women bought his stock because his picture was on the stock certificate. In his will, he disowned all his sons except for William, who was as ruthless in business as his father and the one Cornelius believed capable of maintaining the business empire. At the time of his death, Cornelius Vanderbilt's fortune was estimated at more than $100 million. He willed $95 million to son William but only $500,000 to each of his eight daughters. His wife received $500,000 in cash, their modest New York City home, and 2,000 shares of common stock in New York Central Railroad.

Vanderbilt gave some of his vast fortune to charitable works, leaving the $1 million he had promised for Vanderbilt University and $50,000 to the Church of the Strangers in New York City. He lived modestly, leaving his descendants to build the Vanderbilt houses that characterize America's Gilded Age.

Descendants

Cornelius Vanderbilt was buried in the family vault in the Moravian Cemetery at New Dorp on Staten Island. Three of his daughters and son Cornelius Jeremiah Vanderbilt contested the will on the grounds that their father had insane delusions and was of unsound mind. The unsuccessful court battle lasted more than a year, and Cornelius Jeremiah committed suicide in 1882.

Vanderbilt is the great-great-great grandfather of journalist Anderson Cooper.

Children of Cornelius Vanderbilt & Sophia Johnson:

- Phebe Jane (Vanderbilt) Cross (1814-1878)

- Ethelinda (Vanderbilt) Allen (1817-1889)

- Eliza (Vanderbilt) Osgood (1819-1890)

- William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885)

- Emily Almira (Vanderbilt) Thorn (1823-1896)

- Sophia Johnson (Vanderbilt) Torrance (1825-1912)

- Maria Louisa (Vanderbilt) Clark Niven (1827-1896)

- Frances Lavinia Vanderbilt (1828-1868)

- Cornelius Jeremiah Vanderbilt (1830-1882)

- Mary Alicia (Vanderbilt) LaBau Berger (1834-1902)

- Catherine Juliette (Vanderbilt) Barker LaFitte (1836-1881)

- George Washington Vanderbilt (1839-1864)

Notes

- ↑ Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877) New Netherland Institute. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ↑ Cornelius Vanderbilt: A Long and Useful Life Has Ended The New York Times, January 5, 1877. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ↑ Arthur T. II Vanderbilt, Fortune's Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt (William Morrow & Co, 1989, ISBN 978-0688072797).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Folsom, Burton W, Jr. The Myth of the Robber Barons. Herndon, VA: Young America’s Foundation, 1991. ISBN 0963020315

- MacGregor J.R. Cornelius Vanderbilt - The Commodore: Insight and Analysis Into the Life and Success of America’s First Tycoon. CAC Publishing LLC, 2019. ISBN 978-1950010356

- Sobel, Robert. The Big Board: A History of the New York Stock Market. Washington, DC: Beard Books (reprint), 2000. ISBN 1893122662

- Stiles, T.J. The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt. Knopf, 2009. ISBN 978-0375415425

- Vanderbilt, Arthur T. II. Fortune's Children: The Fall of the House of Vanderbilt. William Morrow & Co, 1989. ISBN 978-0688072797

External links

All links retrieved September 28, 2022.

- Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877) New Netherland Institute

- Cornelius Vanderbilt National Railroad Hall of Fame

- Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877) The Latin Library

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 23:23:16 | 34 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Cornelius_Vanderbilt | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF