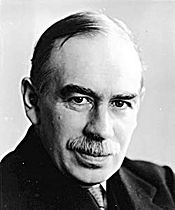

John Maynard Keynes

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia John Maynard Keynes (5 June 1883 - 21 April 1946) was a British economist. [1] In 2010, his native land of Britain (which is deeply in debt) repudiated his economic folly of government deficit spending through the implementation of an austerity budget during a period of economic difficulty.[2][3] Although government certainly is necessary, the more efficient private sector is better at creating economically productive jobs and other economic activity such as investing.

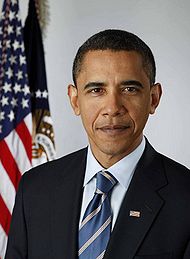

It is ironic that liberals such as Barack Obama advocate Keynesian economic concepts since they are violating one of John Maynard Keynes' key principles. Keynes advocated having governments run budget surpluses during good economic times.[4] In addition, Keynes advocated that governments should increase government spending during difficult times and even engage in deficit spending. Keynes was against large structural deficits as he believed they are a drag on the economy.[5] Liberals such as Barack Obama advocate massive U.S. government spending during a period when the federal government already has a massive amount of existing debt. Furthermore, Obama's colossal government spending was inefficient and did not pull the American economy out of its economic problems, but merely buried the U.S. economy under more debt.

Contents

Biography[edit]

Keynes, the son of a professor, was born in Cambridge, and went on to attend Eton College where he excelled in mathematics, classics, and history. In 1902 he entered King's College, Cambridge to read for a degree in mathematics, however, due to his interest in politics he found himself increasingly drawn toward economics. It was at Cambridge that he found himself under the tutelage of Alfred Marshall and A.C. Pigou. Keynes accepted an economics lectureship at Cambridge funded personally by Marshall. Soon thereafter he took a leave of absence to work for the British Treasury, an institution in which his expertise was frequently called upon during the First World War. Indeed, at the end of the war, Keynes was selected to be the Treasury's principal representative at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The subsequent Treaty of Versailles precipitated Keynes' resignation from the Treasury, as he felt it was draconian in its treatment of Germany.

He returned to Cambridge. His The Economic Consequences of Peace in 1920 was a highly influential slashing attack on the economic disasters that he said would be caused by the Versailles Treaty. He furthered these ideas in 1922 with A Revision of the Treaty, in which he argued that the reparations that Germany was being forced to pay would lead to the collapse of the German economy. In 1923, the German economy entered a period of hyperinflation, which Keynes had not predicted. Keynes found himself becoming increasingly involved in the political process. First supporting the Liberal Party's 1929 "Election Manifesto", and later as an adviser to Ramsay MacDonald's Labour government.

Keynes' magnum opus appeared in 1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. Largely a reaction to the high unemployment that had characterised post-war Britain, the book was among the most revolutionary works of modern economics, signaling a paradigm shift within modern economic thought. As the era went on his prestige and celebrity grew, in 1942 he was made a lord. During the war he advised the Treasury and was Britain's lead representative at the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference. He died of a heart attack in 1946.

Keynesian school of economics[edit]

Keynes was a founding father of modern theoretical macroeconomics. Breaking with the neoclassical orthodoxy of his era, Keynes argued that macroeconomic relationships differ from their microeconomic counterparts. He went on to advocate government intervention into markets and proposed a demand-driven model for money. His theories formed the basis of what came to be known as Keynesian economics.

Keynes rejected socialism—he did not want government to own or even control industry, but rather he wanted the government to optimize the economy though its "fiscal policies," that is, taxes and spending. He was a lifelong member of the British Liberal Party, which held few seats in Parliament after 1920.

Keynes was, with Milton Friedman one of the two most influential economists of the 20th century. Keynes, based at Cambridge University, influenced the economics profession in many ways and was surrounded by students and disciples. He was a major adviser to the Treasury during World War II and helped design the postwar "Bretton Woods" international monetary system.

Keynes' most influential work was in Macroeconomics, where his model of the nation economy emphasized fiscal policy (government spending and taxation) as more useful than regulation or monetary policy. He thus offered a non-socialist solution to the Great Depression. The Keynesian solutions were not accepted for many years, then they were widely adopted in the 1950s in Britain and the United States. Their popularity peaked in the 1960s, just as they came under heavy criticism from Milton Friedman and other conservatives for their theoretical weaknesses, and their inability in practice to deal with the economic crises of the 1970s in which high unemployment, high inflation, and slow growth coexisted.

Keynes, homosexuality and pederasty[edit]

see also: Atheism, pederasty and NAMBLA and John Maynard Keynes and pederasty

Lytton Strachey, his male bed partner, wrote that Keynes was “A liberal and a sodomite, An atheist and a statistician.”[6] Keynes and his friends made numerous trips to the resorts surrounding the Mediterranean. At the resorts, little boys were sold by their families to bordellos which catered to homosexuals.[7]

In 2008, The Atlantic reported:

| “ | Keynes obsessively counted and tabulated almost everything; it was a life-long habit. As a child, he counted the number of front steps of every house on his street. Later he kept a running record (not surprisingly) of his expenses and his golf scores. He also counted and tabulated his sex life.

The first diary is easy: Keynes lists his sexual partners, either by their initials (GLS for Lytton Strachey, DG for Duncan Grant) or their nicknames ("Tressider," for J. T. Sheppard, the King's College Provost). When he apparently had a quick, anonymous hook-up, he listed that sex partner generically: "16-year-old under Etna" and "Lift boy of Vauxhall" in 1911, for instance, and "Jew boy," in 1912.[8] |

” |

Zygmund Dobbs wrote in his work Keynes at Harvard:

| “ | In 1967 the world was startled by the publication of the letters between Lytton Strachey and Maynard Keynes. Undisputed evidence in their private correspondence shows that Keynes was a life-long sexual deviate. What was more shocking was that these practices extended to a large group. Homosexuality, sado-masochism, lesbianism, and the deliberate policy of corrupting the young was the established practice of this large and influential group which eventually set the political and cultural tone for the British Empire.

Keynes’ sexual partner, Lytton Strachey, indicated that their sexual attitudes could be infiltrated, “subtly, through literature, into the bloodstream of the people, and in such a way that they accepted it all quite naturally, if need be, without at first realizing what it was to which they were agreeing.” He further explained, privately, that, “he sought to write in a way that would contribute to an eventual change in our ethical and sexual mores—a change that couldn’t ‘be done in a minute,’ but would unobtrusively permeate the more flexible minds of young people.” This is a classic expression of the Fabian socialist method of seducing the mind. This was written in 1929 when it was already in practice for over forty years. It is no wonder we are reaping the whirlwind of student disorders where drug addiction and homosexuality rule the day.[9] |

” |

Keynes was a bisexual who married Lydia Lopokova. In his work The Cambridge Apostles, 1820-1914: Liberalism, Imagination, and Friendship in British Intellectual and Professional Life, William C. Lubenow expresses the opinion that Keynes was an agnostic.[10]

Keynes the incompetent fraud[edit]

Murry Rothbard wrote in his work Keynes the man:

| “ | The young Keynes displayed no interest whatsoever in economics; his dominant interest was philosophy. In fact, he completed an undergraduate degree at Cambridge without taking a single economics course. Not only did he never take a degree in the subject, but the only economics course Keynes ever took was a single-term graduate course under Alfred Marshall.

...Murray Rothbard says it all: Was Keynes, as Hayek maintained, a “brilliant scholar”? “Scholar” hardly, since Keynes was abysmally read in the economics literature: he was more of a buccaneer, taking a little bit of knowledge and using it to inflict his personality and fallacious ideas upon the world, with a drive continually fueled by an arrogance bordering on egomania. … He possessed the tactical wit to dress up ancient statist and inflationist fallacies with modern, pseudoscientific jargon, making them appear to be the latest findings of economic science. Keynes was thereby able to ride the tidal wave of statism and socialism, of managed and planning economies.[12] |

” |

Dishonesty of Keynes[edit]

Concerning his dishonesty Rothbard wrote:

| “ | Keynes reviewed Ludwig von Mises’s German Treatise on Money and Credit in 1914, slandering it, but it later came out that he did not understand German! As Murray Rothbard notes, ‘This was Keynes to the hilt: to review a book in a language where he was incapable of grasping new ideas, and then to attack that book for not containing anything new, is the height of arrogance and irresponsibility.”[13] | ” |

Rothbard also maintains Keynes purposefully misrepresented the work of English economist Arthur Cecil Pigou.[14]

Keynesian Economics and Stagflation[edit]

In February 2010 the Washington Times reported:

| “ | Prices rose 2.7 percent during 2009, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics' recent update of the Consumer Price Index (CPI). This is a worrisome fact because last year's unemployment rate averaged more than 9 percent. This trend may signal a return of "stagflation," a merger of stagnation and inflation.

In the 1970s, stagflation shocked traditional Keynesian economists, whose models said the economy could not suffer from both high unemployment and rapid inflation at the same time. Unfortunately, the Keynesians were wrong, because an economy obviously can experience both evils simultaneously... It seems every week the Obama administration announces some new tax or mandate that will further handicap businesses. Regardless of the official definitions of recession, the economy will remain sluggish for years to come. But if the Federal Reserve continues with its reckless policies, Americans will experience high inflation on top of high unemployment. As in the late 1970s, Americans will see that the pundits are wrong, because stagflation is very real.[15] |

” |

On June 18, 2011 Business Insider declared:

| “ | There are millions upon millions of Americans that are sitting at home on their couches right now wondering why they lost their jobs and why nobody will hire them. Millions of others are wondering why the only jobs they can get are jobs that a high school student could do. Families all across America are wondering why it seems like their wages never go up but the price of food and the price of gas continue to skyrocket.[16] | ” |

On June 15, 2011 Fox News reported:

| “ | The government said consumer prices jumped 3.6% year-over-year, exceeding estimates for 3.4% and good for the largest increase since October 2008 when they climbed 3.7%. Core prices gained 1.5%, compared with forecasts for 1.4%.

The hotter-than-expected inflation data combined with a dreary report that showed manufacturing activity in New York State unexpectedly contracted in June to send U.S. stock futures tumbling more than 100 points into the red Wednesday morning. The inflation report underscores the Fed's limited options in injecting new stimulus into a U.S. economic recovery that may have stalled out in recent months. That’s because further quantitative easing may only increase the pressure on inflation. “Stagflation is now a growing reality and the 'flation' part ties the hands of the Fed to react with more easing,” Peter Boockvar, equity strategist at Miller Tabak, wrote in a note. “As many of us believe, though, the more easing has added to the 'flation' so maybe less will tame it.” [17] |

” |

Keynesian Economics further elaboration[edit]

Keynesianism centres around the concept of total spending within an economy, what Keynes terms aggregate demand and its effect upon output and inflation. In the eyes of Keynesians, the free market does not necessarily tend toward full employment. Periods such as this were witnessed in the 1930s during the Great Depression, and in the eyes of Keynes could only be solved by increasing the level of expenditure within the economy. In order to do this Keynes advocated increasing government expenditure, frequently in the form of deficit spending, in order to extricate the economy from recession. At the same time Keynes argued that if expenditure within the economy was too high and the economy was at full employment then this would inevitably lead to inflation, as such in periods such as this Keynes advocated tax increases, and a reduction in government expenditure in order to "deflate" the economy. In Keynes view this can level off the peaks and fill in the valleys, solving the problem of depressions.

As is evident, Keynesian thinking went on to influence the fiscal policy of many governments, as well as influencing a generation of economists. "We are all Keynesians now," said President Richard Nixon in 1969.

Keynesianism became the dominant policy in the U.S., Britain and Canada, and a few smaller countries, after 1945. The economic disciples were themselves too young to take much credit—not until the 1960s would they be top government advisers. However Keynesianism suited the needs of many key players. To politicians it gave a formula that demonstrated they were doing something to avoid another Great Depression. Liberals and labor welcomed the high government spending. Businessmen were relieved that Keynesianism a barrier to nationalization of industry or government ownership and socialism. Indeed, the Keynesians paid little attention to control or regulation of specific industries; that was unnecessary said the Keynesian model, because tax rates and government deficits or surpluses were paramount.

Criticism of Keynes and Keynesian Economics[edit]

By the 1970s Keynesianism had run out of steam, and its theoretical model could not account for "stagflation"—the simultaneous case of high inflation and slow growth that dragged on in the 1970s.

New models from the Chicago School of Economics (led by Milton Friedman), were fresher and more appealing. Margaret thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the U.S. explicitly disavowed Keynesianism in favor of Chicago models.

Even in the 1930s Keynes was not without his critics, most notably Friedrich von Hayek, whose critiques of Keynesian theory went on to form the basis of the Supply-side, monetarist, and Austrian School's objections to Keynesianism.

Although Keynes was not a socialist, he poked fun at businessmen and was criticized by conservatives both during the Bretton Woods Conference and afterward for his pro big government stance. His policies about expanded government intervention were criticized for infringing on free markets. Libertarian opponents to Keynes argue that in the long run the invisible hand of the markets would correct any problem that would arise. Keynes responded by noting, "In the long run, we are all dead."

Further reading[edit]

- Felix, David. Keynes: A Critical Life (1999) online edition

- Hutt, W. H. Keynesianism--Retrospect and Prospect: A Critical Restatement of Basic Economic Principles (1963) an attack on his theories by a conservative economist. online edition

- Keynes, Milo, ed. Essays on John Maynard Keynes, (1975)

- Harrod, Roy. The Life of John Maynard Keynes, (1951)

- Moggridge, D. E. Maynard Keynes: An Economist's Biography (1995) online edition

- O'Donnell R. M. Keynes: Philosophy, Economics & Politics. (1989).

- Patinkin, Don. "Keynes, John Maynard", in The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, 1987, pp. 19–41.

- Skidelsky, Robert. John Maynard Keynes: Hopes Betrayed 1883-1920, (1992), the standard scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- John Maynard Keynes: The Economist as Saviour 1920-1937, (1994)

- John Maynard Keynes: Fighting for Britain 1937-1946 (2001) excerpt and text search

- John Maynard Keynes: 1883-1946: Economist, Philosopher, Statesman (2005) Abridged edition; excerpt and text search

- Skidelsky, Robert. Keynes (1996), 144 pp

Primary sources[edit]

- Keynes John Maynard. The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, 30 Vols., ed. by Sir Austin Robinson and Donald E. Moggridge. (1971–89).

References[edit]

- ↑

- ↑ Will the G8 Repudiate the Philosophy of Living Beyond Our Means?

- ↑ Deathbed of Keynesian Economics will be in the UK

- ↑ EK Brown-Collie and Bruce E. Collier, What Keynes really said about deficit spending, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, Vol. 17, No. 3, Spring, 1995

- ↑ https://money.cnn.com/2010/02/04/news/economy/meltzer_keynes.fortune/

- ↑ http://www.keynesatharvard.org/book/KeynesatHarvard-ch09.html

- ↑ http://www.keynesatharvard.org/book/KeynesatHarvard-ch09.html

- ↑ https://www.theatlantic.com/daily-dish/archive/2008/01/keyness-jew-boy-quickie/220620/

- ↑ http://www.keynesatharvard.org/book/KeynesatHarvard-ch09.html

- ↑ The Cambridge Apostles, 1820-1914: Liberalism, Imagination, and Friendship in British Intellectual and Professional Life, 1998, Cambridge University Press, page 402

- ↑

- ↑ http://centurean2.wordpress.com/2011/03/20/fabian-john-maynard-keynes-the-stealthy-enemy-of-human-freedom/

- ↑ http://centurean2.wordpress.com/2011/03/20/fabian-john-maynard-keynes-the-stealthy-enemy-of-human-freedom/

- ↑ http://centurean2.wordpress.com/2011/03/20/fabian-john-maynard-keynes-the-stealthy-enemy-of-human-freedom/

- ↑ http://washingtontimes.com/news/2010/feb/19/setting-the-stage-for-stagflation/

- ↑ https://www.businessinsider.com/collapse-of-the-economy-2011-5

- ↑ https://www.foxbusiness.com/markets/2011/06/15/core-inflation-posts-largest-increase-since-july-08

External links[edit]

Categories: [Economists] [British History] [Finance] [Liberals] [English People]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/09/2023 17:07:25 | 34 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/John_Maynard_Keynes | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF