Gnosticism

From Nwe

From Nwe Gnosticism is a general term describing various mystically-oriented groups and their teachings, which were most prominent in the first few centuries of the Common Era. It is also applied to later and modern revivals of these teachings. The term gnosticism comes from the Greek word for knowledge, gnosis (γνώσις), referring to esoteric consciousness, which is claimed by gnostics to be the key to unlocking transcendent understanding, self-realization, and/or unity with God.

The origins of gnosticism are not clearly known, but there is general agreement that threads of the teachings must have arisen somewhere in what is today known as the Middle East and Asia Minor—areas in which several cultures could converge and synthesize. Many scholars find the roots of gnosticism in Neoplatonism, which similarly devalues matter and regards the spirit as the true reality. A minority of scholars believe it to be of eastern origin because of its similarities to Buddhist ideas of enlightenment, while others believe it has Mesopotamian or Jewish roots. Gnostic groups became popular around the same time and often in the same places that Christianity did.

Gnosticism was widespread within the early Christian church until the gnostics were expelled in the second and third centuries C.E. Gnosticism was one of the first doctrines to be specifically declared a heresy and gnostic movements were often persecuted as a result. Gnostic groups also suffered under Islamic regimes. The response of orthodoxy to gnosticism significantly defined the evolution of Christian doctrine and church order. After gnostic and orthodox Christianity parted, gnostic Christianity continued as a separate movement in some areas for centuries. However some modern theologians think that several gnostic doctrines were absorbed by Christianity. Gnosticism has reappeared in various forms throughout history and into the contemporary era.

Central to many gnostic beliefs is a dualistic view of the universe, in which matter was seen as essentially illusory while spirit is the only true reality. Thus Christian gnostics emphasized spiritual knowledge and experience, rather than faith and the sacraments of the church, as the key to salvation or unity with God. Jesus, whom gnostics believe came as pure spirit, is set in stark contrast to the Old Testament Creator-God, who as the "Demiurge," the source of the material world, is not the true God. Another pillar of gnostic belief is that salvation lies in attaining gnosis, esoteric knowledge kept secret to all but the initiated. Other ideas, believed by all or some gnostic groups, include: the spiritual (not physical) nature of Jesus' resurrection; that Jesus did not possess a physical body; the femininity of the Holy Spirit (and/or other affirmation of male-female essentials); and that gnostic enlightenment liberates a person from moral constraints.

Probably no single gnostic person or school of thought has believed all of these diverse ideas. Furthermore, a number of heterodox groups and beliefs have been labeled "gnostic" yet have only slender resemblance to the main currents of gnostic thought.

Despite the centuries of historical submersion, gnosticism raises issues that are still important today. Amongst the gnostic ideas, some, no doubt, are believed and actively discussed among the widely divergent schools of thought within contemporary Christianity, while others of the ideas would be uniformly rejected. Some of the ideas are quite resonant with aspects of New Age thought and with aspects of some eastern religions.

Sources

There are two main historical sources for information on gnosticism: critiques by ancient orthodox Church Fathers and the original gnostic writings themselves.

Gnostics were prolific producers of sacred literature whose works of gnostic scripture far outnumbered written orthodox Christian scripture. Due to the Christian policy of destroying heretical books, however, no early gnostic literature was available except in the form of quotations in the writings of Church Fathers until the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. Scholars in the nineteenth century devoted considerable effort to collecting the scattered references in the works of opponents and reassembling gnostic materials.

Several important finds of gnostic manuscripts have been made since, most importantly the Nag Hammadi library. Although we now possess a large collection of gnostic texts, they are still often difficult to relate to the history of gnosticism, due to the esoteric nature of gnostic teaching and difficulties of identifying which teachers or sects were associated with particular texts.

History

Early Jewish Gnosticism

Some scholars, notably Gershom Scholem, believe that Jewish gnosticism predated its Christian counterpart. There is indeed some evidence of Jewish mysticism in the pre-Christian era. This can be seen for example in the philosophical writings of Philo of Alexandria, the revelations of Ezekiel (which produced a vast quantity of later kabbalistic speculation), the apocalyptic sections of the Book of Daniel, and detailed explanations about the angelic world in the apocryphal Book of Enoch. The latter certainly contributed to gnostic descriptions and names of the archons, aeons, etc. (See "Gnostic Cosmology" below).

However, the data supporting a specifically gnostic Jewish worldview during this period is sparse. In later centuries, the works of the kabbalah clearly indicate a type of Jewish gnosticism. It has yet to be demonstrated, however, that this literature did not evolve out the interaction between gnostics and Jews, rather than springing from Judaism itself.

Christian tradition—especially the writings of Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, and Hippolytus—blames the Jewish or Samaritan "sorcerer" Simon Magus as the originator of gnosticism. The Church Fathers described him as founding a gnostic sect that practiced antinomianism—the doctrine that moral laws did not apply to one who had attained salvation or enlightenment. According to the Book of Acts, this Simon was simply a magician whose sin was that he wanted to buy the power of the Holy Spirit for personal gain. It is impossible to say for certain whether his teachings might have constituted a type of gnosticism, Jewish or otherwise.

Christian Gnosticism

Gnosticism can be viewed as one of the three main branches of early Christianity. The others are Jewish Christianity, which was practiced by the disciples of Jesus; and Pauline Christianity, which rejected Jewish traditions. German biblical historian Adolf von Harnack said that while Paul's teachings represented the hellenization of the original Jewish Christianity, gnosticism represented its "extreme hellenization."[1]

For some time, Pauline Christianity and gnostic Christianity coexisted. Gradually, the teachings of the two groups appear to have become more distinct. Certain of Paul's letters teach concepts in accord with gnostic teaching—such as the existence of a "god of this world" who has blinded unbelievers (2 Cor. 4:4), the superiority of the spiritual man over the man of flesh (Rom. 8:5), and the existence of secret spiritual teachings that could not be shared with Christians who were not yet advanced enough to receive them (1 Cor. 3:1-2). So too, the Gospels speak of Christ as a pre-existent being of light (John 1:3-5), the triumph of light over darkness within the believer (Luke 11:36), and the devil as the ruler of the material world (Luke 4:6). Gnostic teachers made great use both of Paul's letters and the gospels, especially Luke and John.

Later Christian scriptures, however, directly attack gnosticism. For example:

- 1 Timothy 1:3-4: "Stay there in Ephesus so that you may command certain men not to teach false doctrines any longer nor to devote themselves to myths and endless genealogies." The letter urges Timothy to "Turn away from godless chatter and the opposing ideas of what is falsely called knowledge (gnosis), which some have professed and in so doing have wandered from the faith." (6:20-21)

- 2 John 7: "For many deceivers have gone out into the world, men who will not acknowledge the coming of Jesus Christ in the flesh; such a one is a deceiver and an antichrist." This passage warns against the gnostic teaching that Jesus was entirely a being of light, whose physical body (and its suffering) was only illusory.

- The short Letter of Jude was written to warn of "certain men… who have secretly slipped in among you. They are godless men, who change the grace of our God into a license for immorality…" (1:4)—a probable reference to gnostic teachers who allegedly taught that Christians could dispense not only with the Jewish kosher and circumcision laws, but also with the commandments against adultery and fornication.

Thus, various gnostic and semi-gnostic sects worked within mainline Christian groups. One such group has been named by contemporary scholars as the "School of Thomas"—those who read the Gospel of Thomas, accepted Jesus as a teacher of mystical truth rather than as a savior who atoned for their sins, and believed the resurrection to be spiritual rather than physical.

An important Christian semi-gnostic leader was Marcion, a mid-second century teacher who gained a significant following in the Church of Rome. Marcion accepted the gnostic proposition that the Hebrew Creator-God was actually the Demiurge described in gnostic literature, and thus a different being from the heavenly father of Jesus Christ. He proposed that the Hebrew Bible scriptures should be rejected by Christians, while accepting only a shortened version of the Gospel of Luke and the letters of Paul as authoritative.

The church's rejection of Marcionism resulted in three important developments: Christianity's formal acceptance of the Jewish God as identical with the God of Christianity, the adoption of the Hebrew Bible, and the creation of lists of authorized Christian scriptures that eventually became the New Testament canon. The church also created creeds and other liturgical formulas to weed out gnostic ideas. For example, the Apostles' Creed specifies that God the Father is the "creator of heaven and earth," thus refuting the gnostic/marcionite idea that the creator of the material world was not God but the Demiurge. It further states that Jesus "suffered" under Pontius Pilate, thus refuting the gnostic idea that Christ did not suffer because he was not tied to his physical body. Furthermore, the creed's affirmation of belief in "the resurrection of the body" refutes the gnostic belief that the resurrection was spiritual, not physical, etc.

Valentinus, Basilides and the Sethians

The second century Christian gnostic teacher of widest renown was Valentinus, who was to found his own school of gnosticism in both Alexandria and Rome. According to Tertullian, Valentinus had been a significant figure in the Roman church at one time. He claimed to have received a revelation directly from the Logos. His human instructor was a certain Theudas, who in turn had supposedly received secret knowledge passed on to him by the Apostle Paul. According to Irenaeus, Valentinus was the author of the Gospel of Truth.

Valentinus lived from about 100–175 C.E. While in Alexandria, where he was born, Valentinus probably would have had contact with another major gnostic teacher, Basilides, and may have been influenced by him. The followers of Basilides can be viewed as forming a distinct sect from the Valentinians, although their views in many ways overlapped. The basic outline of Valentian mythology is summarized in "Gnostic Cosmology" below.

Valentinian gnosticism flourished throughout the early centuries of the common era, and the group's Christian opponents make its vitality clear. A list or heretics composed in 388 C.E., against whom Emperor Constantine I intended legislation, includes the Valentinians. Valentinus' students elaborated on the teachings and materials they received from him. Several varieties of their central myth are known.

Valentinian works probably make up a significant part of the Nag Hammadi library, although some analysts identify the collection's "Sethian" literature as coming from a separate gnostic sect. Several other gnostic groups existed as well, although the evidence for them comes mostly from their opponents. For example, "Ophites" is a blanket term referring to various gnostic sects of this period. Included among them were both the Sethians and the Naasseners, the latter supposedly honoring the Demiurge, whom they identified with the serpent of Genesis, as a hero.

Manichaeism

Manichaeism was a distinct gnostic religion that originated in third century Babylon, a province of Persia at the time, eventually reached from North Africa to China. Named after its prophet, Mani, its teachings moved west into Syria, Northern Arabia, Egypt and North Africa, where the future Saint Augustine was a member from 373-382. From Syria it progressed into Palestine, Asia Minor, and Armenia. There is evidence for Manicheans in Rome and Dalmatia in the fourth century, and also in Gaul and Spain. Many of the members of earlier Christian gnostic sects may have drifted into the orbit of Manichaeism. It possessed an organized clergy, liturgies, scriptures, and monasteries.

A characteristic principle of Manichean theology is its dualism. Mani postulated two natures that existed from the beginning: light and darkness. The Manichees attempted to include various religious traditions in their faith, including Christian gnosticism. Mani described himself as a "disciple of Jesus Christ."

Manichaeism was attacked by imperial edicts, church councils, and polemical writings by critics such as Augustine, but the religion remained strong in the western Roman Empire until the sixth century. In Islamic lands, which normally tolerated both Christianity and Judaism, it was repressed as a form of paganism. In the early years of the Arab conquest, however, Manichaeism found followers in Persia and flourished especially in Central Asia. There, in 762, Manichaeism became the state religion of the Uigar Empire.

The scriptures of Manichaeism were lost until the modern era. However, in the early 1900s, German scholars excavated the ancient site of the Manichaean Uigur Kingdom near Turfan, in Chinese Turkestan, and uncovered hundreds of pages of lost Manichaean scriptures, which are now available in translation.[2]

Medieval Gnosticism

Gnosticism, probably including Manichaeism, exerted an important later influence in the west through the emergence of the Paulicians, Bogomils and Cathari in the middle ages. The Cathari, also called Abigensians, controlled significant areas of Southern France during the twelfth century. Through the Inquisition and the Albigensian Crusade, these gnostic movements were ruthlessly stamped out as heresy by the Roman Catholic Church. Thus, gnosticism was forced underground.

Unfounded accusations of gnosticism were leveled against the Knights Templar, Freemasons, and other disfavored groups. Gnostic ideas can be seen to some extent in the works of alchemists, Rosicrucians and other assorted mystics.

Mandaeanism

A gnostic sect with ancient roots, Mandaeanism is still practiced in small numbers, in parts of southern Iraq and the Iranian province of Khuzestan. The name of the group derives from the term: Mandā d-Heyyi which roughly means "knowledge of life." Although its exact chronological origins are not known, the group looks to John the Baptist as a central figure and teacher. Frequent ritual immersions and vegetarianism play a important part in Mandaean practice. Unlike Christian gnosticism and Manichaeism, Mandaeanism rejects Jesus of Nazareth as teacher of truth, believing him to be false prophet who perverted the teachings of the Baptist.

Significant amounts of early Mandaean scripture survive in the modern era. The primary source text, known as the Genzā Rabbā, has portions identified by some scholars as having been copied as early as the second century C.E. In recent times, the Mandaeans were severely repressed under the regime of Saddam Hussein. With the fall of Saddam, they were legally free to practice their religion in public, but reported significant persecution by non-governmental forces, especially Shiite Muslims, who consider them to be pagan infidels rather than "People of the Book."

Kabbalism

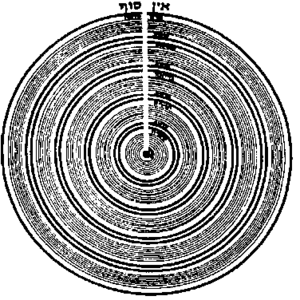

The Jewish tradition known as the kabbalah is a mysticism that is firmly grounded in Jewish monotheism. Nevertheless, some of its literature shows gnostic characteristics. Kabbalists share with gnostics a belief in divine emanations originating from the original God—"the infinite" (Hebrew Ein Sof אין סוף) and extending into the created world; these are called the ten "vessels," or Sefirot. Their concept of the Shekhinah (already an orthodox Jewish concept) as manifesting God's feminine aspect parallels gnosticism's interest in the Divine Feminine.

Among the major kabbalistic texts is the Bahir (“The Brightness”), which was written in Provence in the twelfth century. Some scholars recognize influences from the gnostic Cathari, who were flourishing in the area. The book's characterization of the feminine aspect of God—the Shekhinah—resembles the gnostic Sophia, for example.

Recently, kabbalism has experienced a resurgence in orthodox Jewish circles, and has also found popularity among secular Jews. It has also gained interest among gentiles because of its flexibility and accordance with certain New Age ideas.

Gnostic Christian Teachings

Many gnostic sects were made up of Christians who embraced mystical theories of the nature of Jesus. The Gospel of Thomas, an early semi-gnostic collection of Jesus' sayings that was apparently well known, represents this tendency. In this account, Jesus institutes no sacraments, and his death and resurrection are never mentioned. His role is not to die for mankind's sins, but to impart knowledge to those of his disciples who are able to receive it. "Whoever discovers the interpretation of these sayings," the gospel begins, "will not taste death." Thus it is not by faith in Jesus, but by knowing the true meaning of his teachings, that the believer will enter into eternal life.

While gnosticism was a highly diverse and flexible phenomenon, certain elements can be identified as typifying the movement in its Christian manifestation.

- Gnostics tended toward a dualistic view in which matter was seen as essentially illusory.

- Christian gnostics emphasized spiritual knowledge and experience, rather than faith and the sacraments of the church, as the key to salvation or unity with God.

- They tended to deny the physical resurrection of Jesus, believing this event to be purely spiritual in nature.

- By the mid-second century, Christian gnostics often believed that the God of the Jews was a different, lower being from the True God, having come into existence through the Fall of Sophia (see "Gnostic Cosmology" below).

Many gnostics were highly disciplined and ascetic. Others, however, were accused of teaching that gnosis liberates a person from moral constraint. Many believed in a doctrine known as docetism, the teaching that Jesus only appeared to possess a physical body. It was against this doctrine that John 1:7 famously objects when it states:

- Many deceivers, who do not acknowledge Jesus Christ as coming in the flesh, have gone out into the world. Any such person is the deceiver and the antichrist.

Various gnostic groups taught other doctrines which were rejected by the orthodox church, including:

- that God is androgynous (embracing both masculinity and femininity)

- that God himself is not a trinity but a unity

- that the trinity which emerged from God is Father, Mother, and Son

- that certain disciples (such as Thomas or Mary Magdalene) received special knowledge from Jesus, which was withheld from less enlightened disciples such as Peter

- that women can administer baptism and act as priests

Some gnostics, in common with such Neoplatonic philosophers as Plotinus, held matter to be evil. However, others believed that matter is not evil in and of itself. Rather, it is a person's identification with matter rather than spirit that leads one astray. Gnostics often taught a doctrine of the "bridal chamber," in which the human soul is reunited with God. In association with this idea, they were accused by orthodox Christians of engaging in licentious sexual rituals. Evidence from gnostic sources confirming this, however, is lacking.

Gnostic Cosmology

By the late second century, the gnostic movement had developed a rather involved cosmology. Although it varied widely and should not be oversimplified, a basic outline can be useful for our understanding:

Creation

The "classical" gnostic mythology posits a sort of prologue to the Judeo-Christian version of creation as described in the Book of Genesis. It speaks of an unknown God, defined as immovable, invisible, intangible, and ineffable. God is seen as being androgynous, both male and female, and "all-containing" or sometimes "the uncontained." God may also be referred to as the Monad, or the first Aeon. In gnosticism, God cannot be accurately described in any positive sense through words; it is more possible to say what God isn't. It is only in experiencing God through gnosis that the Deity can be truly understood—but this, too, defies verbal description. For example, the Apocryphon of John states:

He did not lack anything, that he might be completed by it; rather he is always completely perfect in light. He is illimitable, since there is no one prior to him to set limits to him. He is unsearchable, since there exists no one prior to him to examine him. He is immeasurable, since there was no one prior to him to measure him. He is invisible, since no one saw him. He is eternal, since he exists eternally. He is ineffable, since no one was able to comprehend him to speak about him. He is unnameable, since there is no one prior to him to give him a name. He is immeasurable light, which is pure, holy, immaculate. He is ineffable, being perfect in incorruptibility. (He is) not in perfection, nor in blessedness, nor in divinity, but he is far superior. He is not corporeal nor is he incorporeal. He is neither large nor is he small. There is no way to say, “What is his quantity?” or, “What is his quality?,” for no one can know him.

This original God went through a series of emanations, during which its essence is seen as expanding into many successive "generations" of paired male and female beings, called "aeons." Some gnostic texts posit 15-30 such pairs (probably the "endless genealogies" referred to in 2 Timothy, above). These can also be seen as representative of the various attributes of God. Collectively, God and the aeons comprise the sum total of the spiritual universe, known as the Pleroma. One of the first of the aeons—according to one text—was the feminine counterpart of God.

His thought performed a deed and she came forth, namely she who had appeared before him in the shine of his light… the perfect glory in the aeons, the glory of the revelation, she glorified the virginal Spirit and it was she who praised him, because thanks to him, she had come forth. This is the first thought, his image. She became the womb of everything, for it is she who is prior to them all, the Mother-Father, the first man, the holy Spirit, the thrice-male, the thrice-powerful, the thrice-named androgynous one, and the eternal aeon among the invisible ones, and the first to come forth. (Apocryphon of John)

In some versions of the myth, another of the first aeons was Christos, or Christ, who was later sent to earth as the savior. In others, Christ appears to embody several of the characteristics of the first aeons. One Valentinian list (the genealogies vary quite significantly) identifies the following generations of aeons:

- First generation: Bythos or the Monad (the One)

- Second generation: Caen (Power) and Akhana (Love)

- Third generation, emanated from Caen and Akhana: Nous (Nus, Mind) and Aletheia (Veritas, Truth)

- Fourth generation, emanated from Nous and Aletheia: Sermo (the Word) and Vita (the Life)

- Fifth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita: Anthropos (Humanity) and Ecclesia (Church)

- Sixth generation, emanated from Sermo and Vita: Bythios (Profound) and Mixis (Mixture), Ageratos (Never old) and Henosis (Union), Autophyes (Essential nature) and Hedone (Pleasure), Acinetos (Immovable) and Syncrasis (Commixture), Monogenes (Only-begotten) and Macaria (Happiness); emanated from Anthropos and Ecclesia: Paracletus (Comforter) and Pistis (Faith), Patricas (Paternity) and Elpis (Hope), Metricos (Maternity) and Agape (Love), Ainos (Praise) and Synesis (Intelligence), Ecclesiasticus (Son of Ecclesia) and Macariotes (Blessedness), Theletus (Perfection) and Sophia (Wisdom).

At this point in the gnostic cosmology, the universe was still entirely non-material. However, the emanations of God into increasing numbers of aeons led, eventually, to potential instability within the primordial universe. This reached a critical point with the appearance of the aeon most distant from the origin, Sophia.

Fall

Sophia's distance from the Original One produced a sense of anxiety and fear of losing her life, as well as confusion and longing to return to God. In some versions of the myth, Sophia attempts to surmount the rigid hierarchy of the divine nature, in order to approach close to God. In other versions, she imitates God by performing an emanation of her own, without her male counterpart. In both cases, this intransigence causes a crisis within the Pleroma, leading to the creation of the Demiurge.

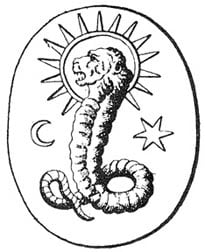

In the Apocryphon of John, the Demiurge is referred to as Yaldabaoth, a "serpent with a lion's head."

And when she saw (the consequences of) her desire, it changed into a form of a lion-faced serpent. And its eyes were like lightning fires which flash. She cast it away from her, outside that place, that no one of the immortal ones might see it, for she had created it in ignorance. (Apocryphon of John)

Sophia hides the Demiurge, but he later escapes. The Demiurge then creates the physical world in which we live. To assist in the completion of his task, the Demiurge spawns a group of entities known collectively as Archons—the demigods and craftsmen of the physical world. Gnostic texts often ascribe them names identical with angels and archangels in Jewish and Christian scriptures.

At this point, the events of the gnostic narrative join with the events of Genesis, with the Demiurge and his cohorts fulfilling the role of the Creator and his angels. The Demiurge declares himself to be the only god, and that none exist superior to him. Thus, humankind became trapped in the Demiurge's web of material illusion, cut off from the true God and source of divine light.

Redemption

Regretting her action, Sophia managed to infuse a spiritual spark or pneuma into the Demiurge's creation. The savior (Christos) comes to Sophia and enables her to see the light again. Christos and Sophia work together to reawaken humans to the Truth. While Sophia remains in the Pleroma, Christos descends to earth in the form of the man Jesus to give men the gnosis they need to rescue themselves from the physical world and return to spiritual reality.

Three types of humans respond differently to Christ's message:

- hylics, bound to the matter, the principle of evil

- psychics, bound to the soul and partly saved from evil

- pneumatics, free to return to the Pleroma if they achieve gnosis

From this typology it can be seen that some human beings are destined to hell while some are predestined to salvation. This idea of predestination of a person to hell or heaven entered Christianity especially through the writings of the former Manichaean St. Augustine of Hippo and was reaffirmed by the Reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin.

Thus Sophia, despite her negative role in the tragedy of creation, plays a positive role in relation to helping humankind to reawaken from "forgetfulness" into the light of truth. In some cases she is seen as the spiritual female counterpart of Christ, the two working as a male-female unit:

The perfect Savior said: "The Son of Man consented with Sophia, his consort, and revealed a great androgynous light. His male name is designated 'Savior, Begetter of All Things'. His female name is designated 'All-Begettress Sophia'. Some call her 'Pistis' (faith). (The Sophia of Jesus, Pistis Sophia)

Some gnostics not only rejected the Jewish God as the Demiurge, but consequently reinterpreted biblical stories so that the adversary of the Hebrew god became a hero. Thus, gnostics sometimes regarded the serpent in the Garden of Eden as a messenger of light who could help humanity free itself of the chains of the Demiurge, or Yaldabaoth. In this version of the myth, Sophia gives wisdom to humankind by way of the serpent, opening the way to gnosis.

Seth, the third son of Adam, was also an important figure in gnostic scriptures. He was introduced to the gnostic teachings by his father and/or his mother, and this knowledge has been preserved throughout the generations.

Modern Gnosticism

Although consistently repressed by the Roman Catholic Church, western gnosticism continued to exist in various underground forms. After the Protestant Reformation and the advent of religious tolerance in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it began to resurface. The Occultism of the nineteenth century has gnostic elements, for example. Hindu teachers from the East found common ground for their teachings among western students of gnostic ideas. By the late twentieth century, reformed gnostic churches and new age gnostic groups were commonplace. Specific examples include:

- William Blake, the nineteenth-century Romantic poet and artist, was apparently well-versed in certain doctrines of the gnostics. However, Blake's personal mythology was complex, and the exact relationship between Blake and the gnosticism remains a point of scholarly contention.

- Carl Jung and his associate G. R. S. Mead worked on trying to understand and explain the gnostic faith from a psychological standpoint. The Jungian movement spawned wide interest in gnosticism.

- Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, founder of theosophy, wrote extensively on gnostic ideas which permeate the various branches of this movement.

- Jules Doinel "re-established" a Gnostic Church in the autumn 1890 in Paris. Founded on rediscovered Cathar documents with a heavy influence of Valentinian cosmology, the church used modified Cathar rituals as sacraments and had a clergy that was both male and female.[3]

- Samael Aun Weor formed a partnership with Swami Sivananda of the Divine Life Society in India and founded the International Gnostic Movement, as well as several gnostic institutions in Latin America.

- Several gnostic denominations exist in the United States. One of them is the Ecclesia Gnostica, with headquarters in Los Angeles. Another is the Apostolic Johannite Church led by Mar Iohannes, using traditional Christian rites with an gnostic interpretation. Iohannes is also president of the North American College of Gnostic Bishops, a group describing itself as dedicated to gnostic growth, while avoiding dogma. Mar Didymos I of the Thomasine Church has reinterpreted Gnosticism emphasizing critical thinking rather than dogmatism.

- Aleister Crowley's Thelema system is influenced by, and bears major features in common with gnosticism.

- Scientology has certain parallels with gnosticism in its emphasis on attaining self-knowledge and attaining the state "Clear."

- Several contemporary Sethian movements emphasize channeled revelation from the spiritual realm, with varying degrees of connection to the traditional gnostic Sethian tradition.

- Various New Age and Human Potential movements combine gnostic ideas with Jungian psychology, numerology, and other mystical teachings. Among them are a number of kabbalistic New Age centers.

- Many gnostic themes can be found in the ideas of Marxism.

Notes

- ↑ A. Harnack. History of Dogma, trans. Neil Buchanan (New York: Dover, 1961).

- ↑ The Gnostic Society Library: Manichaean Writings.gnosis.org. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ↑ See The Eglise Gnostique Apostolique. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aland, Barbara. Festschrift für Hans Jonas. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1978. ISBN 3525581114

- Freke, Timothy and Peter Gandy. The Hermetica: The Lost Wisdom of the Pharaohs. Tarcher, 1999. ISBN 0874779502

- Freke, Timothy and Peter Gandy. Jesus and the Lost Goddess: The Secret Teachings of the Original Christians. Three Rivers Press, 2002. ISBN 000710071X

- Haardt, Robert. Die Gnosis: Wesen und Zeugnisse. Müller, 1967.

- Hoeller, Stephan A. Gnosticism - New Light on the Ancient Tradition of Inner Knowing. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books, 2002. ISBN 0835608166

- Jonas, Hans. Gnosis und spätantiker Geist vol. 2 (1993): 1-2. ISBN 3525538413

- Jonas, Hans.The Gnostic Religion. Beacon, 2001. ISBN 0807058017

- King, Karen L. What is Gnosticism? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003. ISBN 067401071X

- Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim. Gnosis on the Silk Road: Gnostic Texts from Central Asia. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993. ISBN 0060645865

- Layton, Bentley. Prolegomena to the Study of Ancient Gnosticism (in The Social World of the First Christians: Essays in Honor of Wayne A. Meeks). Edited by L. Michael White and O. Larry Yarbrough. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1995. ISBN 0800625854

- Longfellow, Ki. The Secret Magdalene. Brattleboro, VT: Eio Books, 2005. ISBN 0975925539

- Pagels, Elaine. The Gnostic Gospels. New York: Vintage Books, 1979. ISBN 0679724532

- Pagels, Elaine. The Johannine Gospel in Gnostic Exegesis. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 1989. ISBN 1555403344

- Robinson, James. The Nag Hammadi Library. New York: Harper & Row, 1978. ISBN 0060669349

- Williams, Michael. Rethinking Gnosticism: An Argument for Dismantling a Dubious Category. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 0691011273

External links

All links retrieved June 23, 2017.

- The Gnosis Archive

- Gnostics, Gnostic Gospels, & Gnosticism at Early Christian Writings

- Introduction to Gnosticism by M. Alan Kazlev

- Gnosticism: Ancient and Modern – Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance (ReligiousTolerance.org)

- Gnosticism at the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Gnosticism – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Gnosticism – Jewish Encyclopedia

- Apostolic Johannite Church

- French Gnostic Tradition (i.e. Doinel, et al.)

- The North American College of Gnostic Bishops

- The Gnostic Sanctuary

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:07:44 | 227 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gnostic | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF