Moons Of Haumea

From Handwiki

From Handwiki

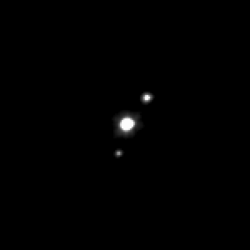

The dwarf planet Haumea has two known moons, Hiʻiaka and Namaka, named after Hawaiian goddesses. These small moons were discovered in 2005, from observations of Haumea made at the large telescopes of the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii.

Haumea's moons are unusual in a number of ways. They are thought to be part of its extended collisional family, which formed billions of years ago from icy debris after a large impact disrupted Haumea's ice mantle. Hiʻiaka, the larger, outermost moon, has large amounts of pure water ice on its surface, which is rare among Kuiper belt objects.[1] Namaka, about one tenth the mass, has an orbit with surprising dynamics: it is unusually eccentric and appears to be greatly influenced by the larger satellite.

History

Two small satellites were discovered around Haumea (which was at that time still designated 2003 EL61) through observations using the W.M. Keck Observatory by a Caltech team in 2005. The outer and larger of the two satellites was discovered 26 January 2005,[2] and formally designated S/2005 (2003 EL61) 1, though nicknamed "Rudolph" by the Caltech team.[3] The smaller, inner satellite of Haumea was discovered on 30 June 2005, formally termed S/2005 (2003 EL61) 2, and nicknamed "Blitzen".[4] On 7 September 2006, both satellites were numbered and admitted into the official minor planet catalogue as (136108) 2003 EL61 I and II, respectively.

The permanent names of these moons were announced, together with that of 2003 EL61, by the International Astronomical Union on 17 September 2008: (136108) Haumea I Hiʻiaka and (136108) Haumea II Namaka.[5] Each moon was named after a daughter of Haumea, the Hawaiian goddess of fertility and childbirth. Hiʻiaka is the goddess of dance and patroness of the Big Island of Hawaii, where the Mauna Kea Observatory is located.[6] Nāmaka is the goddess of water and the sea; she cooled her sister Pele's lava as it flowed into the sea, turning it into new land.[7]

In her legend, Haumea's many children came from different parts of her body.[7] The dwarf planet Haumea appears to be almost entirely made of rock, with only a superficial layer of ice; most of the original icy mantle is thought to have been blasted off by the impact that spun Haumea into its current high speed of rotation, where the material formed into the small Kuiper belt objects in Haumea's collisional family. There could therefore be additional outer moons, smaller than Namaka, that have not yet been detected. However, HST observations have confirmed that no other moons brighter than 0.25% of the brightness of Haumea exist within the closest tenth of the distance (0.1% of the volume) where they could be held by Haumea's gravitational influence (its Hill sphere).[8] This makes it unlikely that any more exist.

Surface properties

Hiʻiaka is the outer and, at roughly 310 km in diameter, the larger and brighter of the two moons.[9] Strong absorption features observed at 1.5, 1.65 and 2 µm in its infrared spectrum are consistent with nearly pure crystalline water ice covering much of its surface. The unusual spectrum, and its similarity to absorption lines in the spectrum of Haumea, led Brown and colleagues to conclude that it was unlikely that the system of moons was formed by the gravitational capture of passing Kuiper belt objects into orbit around the dwarf planet: instead, the Haumean moons must be fragments of Haumea itself.[10]

The sizes of both moons are calculated with the assumption that they have the same infrared albedo as Haumea, which is reasonable as their spectra show them to have the same surface composition. Haumea's albedo has been measured by the Spitzer Space Telescope: from ground-based telescopes, the moons are too small and close to Haumea to be seen independently.[11] Based on this common albedo, the inner moon, Namaka, which is a tenth the mass of Hiʻiaka, would be about 170 km in diameter.[12]

The Hubble Space Telescope (HST) has adequate angular resolution to separate the light from the moons from that of Haumea. Photometry of the Haumea triple system with HST's NICMOS camera has confirmed that the spectral line at 1.6 µm that indicates the presence of water ice is at least as strong in the moons' spectra as in Haumea's spectrum.[11]

The moons of Haumea are too faint to detect with telescopes smaller than about 2 metres in aperture, though Haumea itself has a visual magnitude of 17.5, making it the third-brightest object in the Kuiper belt after Pluto and Makemake, and easily observable with a large amateur telescope.

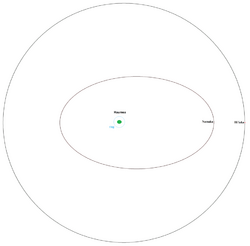

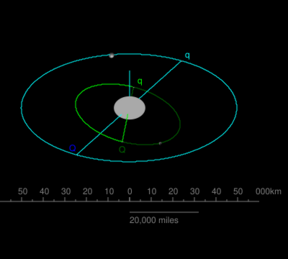

Orbital characteristics

Hiʻiaka orbits Haumea nearly circularly every 49 days.[9] Namaka orbits Haumea in 18 days in a moderately elliptical, non-Keplerian orbit, and as of 2008 was inclined 13° with respect to Hiʻiaka, which perturbs its orbit.[4] Because the impact that created the moons of Haumea is thought to have occurred in the early history of the Solar System,[13] over the following billions of years it should have been tidally damped into a more circular orbit. Namaka's orbit has likely been disturbed by orbital resonances with the more-massive Hiʻiaka due to converging orbits as they moved outward from Haumea due to tidal dissipation.[4] They may have been caught in and then escaped from orbital resonance several times; they currently are in or at least close to an 8:3 resonance.[4] This resonance strongly perturbs Namaka's orbit, which has a current precession of its argument of periapsis by about −6.5° per year, a precession period of 55 years.[8]

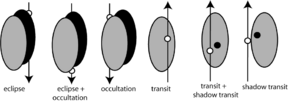

At present, the orbits of the Haumean moons appear almost exactly edge-on from Earth, with Namaka having periodically occulted Haumea from 2009 to 2011.[14][15] Observation of such transits would provide precise information on the size and shape of Haumea and its moons, as happened in the late 1980s with Pluto and Charon.[16] The tiny change in brightness of the system during these occultations required at least a medium-aperture professional telescope for detection.[17] Hiʻiaka last occulted Haumea in 1999, a few years before its discovery, and will not do so again for some 130 years.[18] However, in a situation unique among regular satellites, the great torquing of Namaka's orbit by Hiʻiaka preserved the viewing angle of Namaka–Haumea transits for several more years.[4][17]

| Label [note 1] |

Name (pronunciation) |

Mean diameter (km) |

Mass (×1018 kg) |

Semi-major axis (km) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination (°)[note 2] | Discovery date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ring) | ≈ 70 | 2285±8[20] | 0.489438±0.000012[20][lower-alpha 1] | [approximately same as Haumea's equator] | January 2017 | ||||

| II | Namaka | /nɑːˈmɑːkə/ | ≈ 170? | 1.79±1.48[8] (≈ 0.05% Haumea) |

25657±91[8] | 18.2783±0.0076[8][note 3] | 0.249±0.015[8][note 4] | 113.013±0.075[8] (13.41±0.08 from Hiʻiaka)[note 4] |

June 2005 |

| I | Hiʻiaka | /hiːʔiːˈɑːkə/ | ≈ 310 | 17.9±1.1[8] (≈ 0.5% Haumea) |

49880±198[8] | 49.462±0.083[8][note 3] | 0.0513±0.0078[8] | 126.356±0.064[8] | January 2005 |

Notes

- ↑ Label refers to the Roman numeral attributed to each moon in order of their discovery.[19]

- ↑ Orbital inclinations of Namaka and Hiʻiaka are with respect to Haumea's orbit.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Using Kepler's third law.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 As of 2008: Namaka's eccentricity and inclination are variable due to perturbation.

- ↑ Based on a 3:1 resonance with Haumea's rotation period.

References

- ↑ Barkume, K. M.; Brown, M. E.; Schaller, E. L. (2006). "Water Ice on the Satellite of Kuiper Belt Object 2003 EL61". The Astrophysical Journal 640 (1): L87–L89. doi:10.1086/503159. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...640L..87B. http://www.gps.caltech.edu/~mbrown/papers/ps/rudolph.pdf.

- ↑ M. E. Brown; A. H. Bouchez; D. Rabinowitz; R. Sari; C. A. Trujillo; M. van Dam; R. Campbell; J. Chin et al. (2005-09-02). "Keck Observatory Laser Guide Star Adaptive Optics Discovery and Characterization of a Satellite to the Large Kuiper Belt Object 2003 EL61". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 632 (1): L45–L48. doi:10.1086/497641. Bibcode: 2005ApJ...632L..45B. http://authors.library.caltech.edu/34486/1/1538-4357_632_1_L45.pdf.

- ↑ Kenneth Chang (2007-03-20). "Piecing Together the Clues of an Old Collision, Iceball by Iceball". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/20/science/space/20kuip.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 D. Ragozzine; M. E. Brown. "Orbits and Masses of the 2003 EL61 Satellite System". AAS DPS conference 2008. http://www.abstractsonline.com/viewer/viewAbstract.asp?CKey={421E1C09-F75A-4ED0-916C-8C0DDB81754D}&MKey={35A8F7D5-A145-4C52-8514-0B0340308E94}&AKey={AAF9AABA-B0FF-4235-8AEC-74F22FC76386}&SKey={545CAD5F-068B-4FFC-A6E2-1F2A0C6ED978}.

- ↑ "News Release – IAU0807: IAU names fifth dwarf planet Haumea". International Astronomical Union. 2008-09-17. http://www.iau.org/public_press/news/release/iau0807/.

- ↑ "Dwarf Planets and their Systems". US Geological Survey Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/append7.html#DwarfPlanets.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Robert D. Craig (2004). Handbook of Polynesian Mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 128. ISBN 1-57607-894-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=LOZuirJWXvUC&q=haumea&pg=PA128.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 Ragozzine, D.; Brown, M.E. (2009). "Orbits and Masses of the Satellites of the Dwarf Planet Haumea = 2003 EL61". The Astronomical Journal 137 (6): 4766–4776. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/6/4766. Bibcode: 2009AJ....137.4766R.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brown, M. E.; Van Dam, M. A.; Bouchez, A. H.; Le Mignant, D.; Campbell, R. D.; Chin, J. C. Y.; Conrad, A.; Hartman, S. K. et al. (2006). "Satellites of the Largest Kuiper Belt Objects". The Astrophysical Journal 639 (1): L43–L46. doi:10.1086/501524. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...639L..43B. http://web.gps.caltech.edu/~mbrown/papers/ps/gab.pdf. Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- ↑ Michael E. Brown. "The largest Kuiper belt objects". Caltech. http://www.gps.caltech.edu/~mbrown/papers/ps/kbochap.pdf.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Fraser, W.C.; Brown, M.E. (2009). "NICMOS Photometry of the Unusual Dwarf Planet Haumea and its Satellites". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 695 (1): L1–L3. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/695/1/L1. Bibcode: 2009ApJ...695L...1F.

- ↑ "(136108) Haumea, Hi'iaka, and Namaka". Johnstonsarchive.net. http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/astro/astmoons/am-136108.html.

- ↑ Michael E. Brown; Kristina M. Barkume; Darin Ragozzine; Emily L. Schaller (2007-01-19). "A collisional family of icy objects in the Kuiper belt". Nature 446 (7133): 294–296. doi:10.1038/nature05619. PMID 17361177. Bibcode: 2007Natur.446..294B. https://authors.library.caltech.edu/34346/2/nature05619-s1.pdf.

- ↑ "IAU Circular 8949". International Astronomical Union. 17 September 2008. http://www.cfa.harvard.edu/~fabrycky/EL61/.

- ↑ Brown, M.. "Mutual events of Haumea and Namaka". http://web.gps.caltech.edu/~mbrown/2003EL61/mutual/.

- ↑ Lucy-Ann Adams McFadden; Paul Robert Weissman; Torrence V. Johnson (2007). Encyclopedia of the Solar System. ISBN 978-0-12-088589-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=G7UtYkLQoYoC&q=mutual+event+pluto&pg=PA545. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 D. C. Fabrycky; M. J. Holman; D. Ragozzine; M. E. Brown et al. (2008). "Mutual Events of 2003 EL61 and its Inner Satellite". AAS DPS Conference 2008 40: 36.08. Bibcode: 2008DPS....40.3608F.

- ↑ Mike Brown (2008-05-18). "Moon shadow Monday (fixed)". Mike Brown's Planets. http://www.mikebrownsplanets.com/2008/05/moon-shadow-monday-fixed.html.

- ↑ "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Page/Planets.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ortiz, J. L.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Sicardy, B. et al. (2017). "The size, shape, density and ring of the dwarf planet Haumea from a stellar occultation". Nature 550 (7675): 219–223. doi:10.1038/nature24051. PMID 29022593. Bibcode: 2017Natur.550..219O.

External links

- Animation of the orbits of Haumea's moons

- International Year of Astronomy 2009 podcast: Dwarf Planet Haumea (Darin Ragozzine)

- Brown's publication describing the discovery of Hiʻiaka

- Paper describing the composition of Hiʻiaka

|

Categories: [Lists of moons]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 07/19/2024 11:56:28 | 32 views

☰ Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Astronomy:Moons_of_Haumea | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

KSF

KSF