World Health Organization

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki

| |

| |

| Abbreviation | WHO |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

|

| Formation | 7 April 1948 |

| Type | United Nations specialised agency |

| Legal status | Active |

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

Head | Tedros Adhanom (Director-General) Soumya Swaminathan (deputy Director-General) Jane Ellison (deputy Director-General) |

Parent organization | United Nations Economic and Social Council |

| Website | www.who.int |

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health.[1] The WHO Constitution, which establishes the agency's governing structure and principles, states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health."[2] It is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, with six semi-autonomous regional offices and 150 field offices worldwide.

The WHO was established by constitution on 7 April 1948,[3] which is commemorated as World Health Day.[4] The first meeting of the World Health Assembly (WHA), the agency's governing body, took place on 24 July 1948. The WHO incorporated the assets, personnel, and duties of the League of Nations' Health Organisation and the Office International d'Hygiène Publique, including the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).[5] Its work began in earnest in 1951 following a significant infusion of financial and technical resources.[6]

The WHO's broad mandate includes advocating for universal healthcare, monitoring public health risks, coordinating responses to health emergencies, and promoting human health and well being.[7] It provides technical assistance to countries, sets international health standards and guidelines, and collects data on global health issues through the World Health Survey. Its flagship publication, the World Health Report, provides expert assessments of global health topics and health statistics on all nations.[8] The WHO also serves as a forum for summits and discussions on health issues.[1]

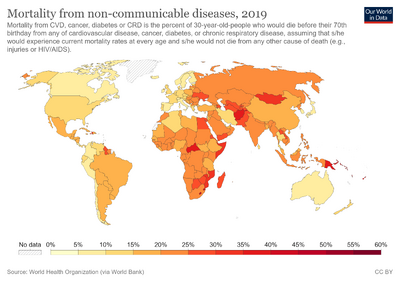

The WHO has played a leading role in several public health achievements, most notably the eradication of smallpox, the near-eradication of polio, and the development of an Ebola vaccine. Its current priorities include communicable diseases, particularly HIV/AIDS, Ebola, malaria and tuberculosis; non-communicable diseases such as heart disease and cancer; healthy diet, nutrition, and food security; occupational health; and substance abuse.

The WHA, composed of representatives from all 194 member states, serves as the agency's supreme decision-making body. It also elects and advises an Executive Board made up of 34 health specialists. The WHA convenes annually and is responsible for selecting the Director-General, setting goals and priorities, and approving the WHO's budget and activities. The current Director-General is Tedros Adhanom, former Health Minister and Foreign Minister of Ethiopia, who began his five-year term on 1 July 2017.[9]

The WHO relies on contributions from member states (both assessed and voluntary) and private donors for funding. As of 2018, it has a budget of over $4.2 billion, a large part of which comes from voluntary contributions from member states.[1] Contributions are assessed by a formula which includes GDP per capita. In 2018–19, the US contributed 15% of the WHO's $5.6 billion budget, the EU and its member states contributed 11%, while China contributed 0.2%.[10] The agency is part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Group.

History and development[edit | edit source]

Origins[edit | edit source]

The International Sanitary Conferences, originally held on 23 June 1851, were the first predecessors of the WHO. A series of 14 conferences that lasted from 1851 to 1938, the International Sanitary Conferences worked to combat many diseases, chief among them cholera, yellow fever, and the bubonic plague. The conferences were largely ineffective until the seventh, in 1892; when an International Sanitary Convention that dealt with cholera was passed.

Five years later, a convention for the plague was signed.[11] In part as a result of the successes of the Conferences, the Pan-American Sanitary Bureau (1902), and the Office International d'Hygiène Publique (1907) were soon founded. When the League of Nations was formed in 1920, they established the Health Organization of the League of Nations. After World War II, the United Nations absorbed all the other health organizations, to form the WHO.[12]

Establishment[edit | edit source]

During the 1945 United Nations Conference on International Organization, Szeming Sze, a delegate from the Republic of China, conferred with Norwegian and Brazilian delegates on creating an international health organization under the auspices of the new United Nations. After failing to get a resolution passed on the subject, Alger Hiss, the Secretary General of the conference, recommended using a declaration to establish such an organization. Sze and other delegates lobbied and a declaration passed calling for an international conference on health.[13] The use of the word "world", rather than "international", emphasized the truly global nature of what the organization was seeking to achieve.[14] The constitution of the World Health Organization was signed by all 51 countries of the United Nations, and by 10 other countries, on 22 July 1946.[15] It thus became the first specialized agency of the United Nations to which every member subscribed.[16] Its constitution formally came into force on the first World Health Day on 7 April 1948, when it was ratified by the 26th member state.[15]

The first meeting of the World Health Assembly finished on 24 July 1948, having secured a budget of US$5 million (then GB£1,250,000) for the 1949 year. Andrija Štampar was the Assembly's first president, and G. Brock Chisholm was appointed Director-General of WHO, having served as Executive Secretary during the planning stages.[14] Its first priorities were to control the spread of malaria, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections, and to improve maternal and child health, nutrition and environmental hygiene.[17] Its first legislative act was concerning the compilation of accurate statistics on the spread and morbidity of disease.[14] The logo of the World Health Organization features the Rod of Asclepius as a symbol for healing.[18]

Operational history of WHO[edit | edit source]

1947: The WHO established an epidemiological information service via telex, and by 1950 a mass tuberculosis inoculation drive using the BCG vaccine was under way.

1955: The malaria eradication programme was launched, although it was later altered in objective. 1955 saw the first report on diabetes mellitus and the creation of the International Agency for Research on Cancer.[19]

1958: Viktor Zhdanov, Deputy Minister of Health for the USSR, called on the World Health Assembly to undertake a global initiative to eradicate smallpox, resulting in Resolution WHA11.54.[20] At this point, 2 million people were dying from smallpox every year.[citation needed]

1966: The WHO moved its headquarters from the Ariana wing at the Palace of Nations to a newly constructed HQ elsewhere in Geneva.[19][21]

1967: The WHO intensified the global smallpox eradication by contributing $2.4 million annually to the effort and adopted a new disease surveillance method.[22][23] The initial problem the WHO team faced was inadequate reporting of smallpox cases. WHO established a network of consultants who assisted countries in setting up surveillance and containment activities.[24] The WHO also helped contain the last European outbreak in Yugoslavia in 1972.[25] After over two decades of fighting smallpox, the WHO declared in 1979 that the disease had been eradicated – the first disease in history to be eliminated by human effort.[26]

1967: The WHO launched the Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases and the World Health Assembly voted to enact a resolution on Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation, with a focus on community-driven care.

1974: The Expanded Programme on Immunization and the control programme of onchocerciasis was started, an important partnership between the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the World Bank.

1977: The first list of essential medicines was drawn up, and a year later the ambitious goal of "Health For All" was declared.

1986: The WHO began its global programme on HIV/AIDS. Two years later preventing discrimination against sufferers was attended to and in 1996 UNAIDS was formed.

1988: The Global Polio Eradication Initiative was established.[19]

1998: WHO's Director-General highlighted gains in child survival, reduced infant mortality, increased life expectancy and reduced rates of "scourges" such as smallpox and polio on the fiftieth anniversary of WHO's founding. He, did, however, accept that more had to be done to assist maternal health and that progress in this area had been slow.[27]

2000: The Stop TB Partnership was created along with the UN's formulation of the Millennium Development Goals.

2001: The measles initiative was formed, and credited with reducing global deaths from the disease by 68% by 2007.

2002: The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria was drawn up to improve the resources available.[19]

2006: The organization endorsed the world's first official HIV/AIDS Toolkit for Zimbabwe, which formed the basis for global prevention, treatment, and support the plan to fight the AIDS pandemic.[28]

Overall focus[edit | edit source]

The WHO's Constitution states that its objective "is the attainment by all people of the highest possible level of health".[29]

The WHO fulfills this objective through its functions as defined in its Constitution: (a) To act as the directing and coordinating authority on international health work; (b) To establish and maintain effective collaboration with the United Nations, specialized agencies, governmental health administrations, professional groups and such other organizations as may be deemed appropriate; (c) To assist Governments, upon request, in strengthening health services; (d) To furnish appropriate technical assistance and, in emergencies, necessary aid upon the request or acceptance of Governments; (e) To provide or assist in providing, upon the request of the United Nations, health services and facilities to special groups, such as the peoples of trust territories; (f) To establish and maintain such administrative and technical services as may be required, including epidemiological and statistical services; (g) to stimulate and advance work to eradicate epidemic, endemic and other diseases; (h) To promote, in co-operation with other specialized agencies where necessary, the prevention of accidental injuries; (i) To promote, in co-operation with other specialized agencies where necessary, the improvement of nutrition, housing, sanitation, recreation, economic or working conditions and other aspects of environmental hygiene; (j) To promote co-operation among scientific and professional groups which contribute to the advancement of health; (k) To propose conventions, agreements and regulations, and make recommendations with respect to international health matters and to perform.[citation needed]

As of 2012[update], the WHO has defined its role in public health as follows:[30]

- providing leadership on matters critical to health and engaging in partnerships where joint action is needed;

- shaping the research agenda and stimulating the generation, translation, and dissemination of valuable knowledge;[31]

- setting norms and standards and promoting and monitoring their implementation;

- articulating ethical and evidence-based policy options;

- providing technical support, catalysing change, and building sustainable institutional capacity; and

- monitoring the health situation and assessing health trends.

- CRVS (civil registration and vital statistics) to provide monitoring of vital events (birth, death, wedding, divorce).[32]

Communicable diseases[edit | edit source]

The 2012–2013 WHO budget identified 5 areas among which funding was distributed.[33] Two of those five areas related to communicable diseases: the first, to reduce the "health, social and economic burden" of communicable diseases in general; the second to combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis in particular.[33]

As of 2015, the World Health Organization has worked within the UNAIDS network and strives to involve sections of society other than health to help deal with the economic and social effects of HIV/AIDS.[34] In line with UNAIDS, WHO has set itself the interim task between 2009 and 2015 of reducing the number of those aged 15–24 years who are infected by 50%; reducing new HIV infections in children by 90%; and reducing HIV-related deaths by 25%.[35]

During the 1970s, WHO had dropped its commitment to a global malaria eradication campaign as too ambitious, it retained a strong commitment to malaria control. WHO's Global Malaria Programme works to keep track of malaria cases, and future problems in malaria control schemes. As of 2012, the WHO was to report as to whether RTS,S/AS01, were a viable malaria vaccine. For the time being, insecticide-treated mosquito nets and insecticide sprays are used to prevent the spread of malaria, as are antimalarial drugs – particularly to vulnerable people such as pregnant women and young children.[36]

Between 1990 and 2010, WHO's help has contributed to a 40% decline in the number of deaths from tuberculosis, and since 2005, over 46 million people have been treated and an estimated 7 million lives saved through practices advocated by WHO. These include engaging national governments and their financing, early diagnosis, standardising treatment, monitoring of the spread and effect of tuberculosis and stabilising the drug supply. It has also recognized the vulnerability of victims of HIV/AIDS to tuberculosis.[37]

In 1988, WHO launched the Global Polio Eradication Initiative to eradicate polio.[38] It has also been successful in helping to reduce cases by 99% since which partnered WHO with Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and smaller organizations. As of 2011[update], it has been working to immunize young children and prevent the re-emergence of cases in countries declared "polio-free".[39]

Non-communicable diseases[edit | edit source]

Another of the thirteen WHO priority areas is aimed at the prevention and reduction of "disease, disability and premature deaths from chronic noncommunicable diseases, mental disorders, violence and injuries, and visual impairment".[33][40] The Division of Noncommunicable Diseases for Promoting Health through the Life-course Sexual and Reproductive Health has published the magazine, Entre Nous, across Europe since 1983.[41]

Environmental health[edit | edit source]

The WHO estimates that 12.6 million people died as a result of living or working in an unhealthy environment in 2012 – this accounts for nearly 1 in 4 of total global deaths. Environmental risk factors, such as air, water and soil pollution, chemical exposures, climate change, and ultraviolet radiation, contribute to more than 100 diseases and injuries. This can result in a number of pollution-related diseases.[42]

- 2018 (30 October – 1 November) : 1 WHO's first global conference on air pollution and health (Improving air quality, combatting climate change – saving lives) ; organized in collaboration with UN Environment, World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the secretariat of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)[43]

Life course and life style[edit | edit source]

WHO works to "reduce morbidity and mortality and improve health during key stages of life, including pregnancy, childbirth, the neonatal period, childhood and adolescence, and improve sexual and reproductive health and promote active and healthy aging for all individuals".[33][44]

It also tries to prevent or reduce risk factors for "health conditions associated with use of tobacco, alcohol, drugs and other psychoactive substances, unhealthy diets and physical inactivity and unsafe sex".[33][45][46]

The WHO works to improve nutrition, food safety and food security and to ensure this has a positive effect on public health and sustainable development.[33]

In April 2019, the WHO released new recommendations stating that children between the ages of two and five should spend no more than one hour per day engaging in sedentary behavior in front of a screen and that children under two should not be permitted any sedentary screen time.[47]

Surgery and trauma care[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization promotes road safety as a means to reduce traffic-related injuries.[48] It has also worked on global initiatives in surgery, including emergency and essential surgical care,[49] trauma care,[50] and safe surgery.[51] The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist is in current use worldwide in the effort to improve patient safety.[52]

Emergency work[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization's primary objective in natural and man-made emergencies is to coordinate with member states and other stakeholders to "reduce avoidable loss of life and the burden of disease and disability."[33]

On 5 May 2014, WHO announced that the spread of polio was a world health emergency – outbreaks of the disease in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East were considered "extraordinary".[53][54]

On 8 August 2014, WHO declared that the spread of Ebola was a public health emergency; an outbreak which was believed to have started in Guinea had spread to other nearby countries such as Liberia and Sierra Leone. The situation in West Africa was considered very serious.[55]

On 30 January 2020, the WHO declared the COVID-19 pandemic was a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).[56]

Health policy[edit | edit source]

WHO addresses government health policy with two aims: firstly, "to address the underlying social and economic determinants of health through policies and programmes that enhance health equity and integrate pro-poor, gender-responsive, and human rights-based approaches" and secondly "to promote a healthier environment, intensify primary prevention and influence public policies in all sectors so as to address the root causes of environmental threats to health".[33]

The organization develops and promotes the use of evidence-based tools, norms and standards to support member states to inform health policy options. It oversees the implementation of the International Health Regulations, and publishes a series of medical classifications; of these, three are over-reaching "reference classifications": the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD), the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI).[57] Other international policy frameworks produced by WHO include the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (adopted in 1981),[58] Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (adopted in 2003)[59] the Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel (adopted in 2010)[60] as well as the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and its pediatric counterpart.

In terms of health services, WHO looks to improve "governance, financing, staffing and management" and the availability and quality of evidence and research to guide policy. It also strives to "ensure improved access, quality and use of medical products and technologies".[33] WHO – working with donor agencies and national governments – can improve their use of and their reporting about their use of research evidence.[61]

Governance and support[edit | edit source]

The remaining two of WHO's thirteen identified policy areas relate to the role of WHO itself:[33]

- "to provide leadership, strengthen governance and foster partnership and collaboration with countries, the United Nations system, and other stakeholders in order to fulfill the mandate of WHO in advancing the global health agenda"; and

- "to develop and sustain WHO as a flexible, learning organization, enabling it to carry out its mandate more efficiently and effectively".

Partnerships[edit | edit source]

The WHO along with the World Bank constitute the core team responsible for administering the International Health Partnership (IHP+). The IHP+ is a group of partner governments, development agencies, civil society, and others committed to improving the health of citizens in developing countries. Partners work together to put international principles for aid effectiveness and development co-operation into practice in the health sector.[62]

The organization relies on contributions from renowned scientists and professionals to inform its work, such as the WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization,[63] the WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy,[64] and the WHO Study Group on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice.[65]

WHO runs the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, targeted at improving health policy and systems.[66]

WHO also aims to improve access to health research and literature in developing countries such as through the HINARI network.[67]

WHO collaborates with The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, UNITAID, and the United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief[68] to spearhead and fund the development of HIV programs.

WHO created the Civil Society Reference Group on HIV,[68] which brings together other networks that are involved in policy making and the dissemination of guidelines.

WHO, a sector of the United Nations, partners with UNAIDS[68] to contribute to the development of HIV responses in different areas of the world.

WHO facilitates technical partnerships through the Technical Advisory Committee on HIV,[69] which they created to develop WHO guidelines and policies.

In 2014, WHO released the Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life in a joint publication with the Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance, an affiliated NGO working collaboratively with the WHO to promote palliative care in national and international health policy.[70][71]

Public health education and action[edit | edit source]

Each year, the organization marks World Health Day and other observances focusing on a specific health promotion topic. World Health Day falls on 7 April each year, timed to match the anniversary of WHO's founding. Recent themes have been vector-borne diseases (2014), healthy ageing (2012) and drug resistance (2011).[72]

The other official global public health campaigns marked by WHO are World Tuberculosis Day, World Immunization Week, World Malaria Day, World No Tobacco Day, World Blood Donor Day, World Hepatitis Day, and World AIDS Day.

As part of the United Nations, the World Health Organization supports work towards the Millennium Development Goals.[73] Of the eight Millennium Development Goals, three – reducing child mortality by two-thirds, to reduce maternal deaths by three-quarters, and to halt and begin to reduce the spread of HIV/AIDS – relate directly to WHO's scope; the other five inter-relate and affect world health.[74]

Data handling and publications[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization works to provide the needed health and well-being evidence through a variety of data collection platforms, including the World Health Survey covering almost 400,000 respondents from 70 countries,[75] and the Study on Global Aging and Adult Health (SAGE) covering over 50,000 persons over 50 years old in 23 countries.[76] The Country Health Intelligence Portal (CHIP), has also been developed to provide an access point to information about the health services that are available in different countries.[77] The information gathered in this portal is used by the countries to set priorities for future strategies or plans, implement, monitor, and evaluate it.

The WHO has published various tools for measuring and monitoring the capacity of national health systems[78] and health workforces.[79] The Global Health Observatory (GHO) has been the WHO's main portal which provides access to data and analyses for key health themes by monitoring health situations around the globe.[80]

The WHO Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS), the WHO Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQOL), and the Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA) provide guidance for data collection.[81] Collaborative efforts between WHO and other agencies, such as through the Health Metrics Network, also aim to provide sufficient high-quality information to assist governmental decision making.[82] WHO promotes the development of capacities in member states to use and produce research that addresses their national needs, including through the Evidence-Informed Policy Network (EVIPNet).[83] The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO/AMRO) became the first region to develop and pass a policy on research for health approved in September 2009.[84]

On 10 December 2013, a new WHO database, known as MiNDbank, went online. The database was launched on Human Rights Day, and is part of WHO's QualityRights initiative, which aims to end human rights violations against people with mental health conditions. The new database presents a great deal of information about mental health, substance abuse, disability, human rights, and the different policies, strategies, laws, and service standards being implemented in different countries.[85] It also contains important international documents and information. The database allows visitors to access the health information of WHO member states and other partners. Users can review policies, laws, and strategies and search for the best practices and success stories in the field of mental health.[85]

The WHO regularly publishes a World Health Report, its leading publication, including an expert assessment of a specific global health topic.[86] Other publications of WHO include the Bulletin of the World Health Organization,[87] the Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal (overseen by EMRO),[88] the Human Resources for Health (published in collaboration with BioMed Central),[89] and the Pan American Journal of Public Health (overseen by PAHO/AMRO).[90]

In 2016, the World Health Organization drafted a global health sector strategy on HIV. In the draft, the World Health Organization outlines its commitment to ending the AIDS epidemic by the year 2030[91] with interim targets for the year 2020. To make achievements towards these targets, the draft lists actions that countries and the WHO can take, such as a commitment to universal health coverage, medical accessibility, prevention and eradication of disease, and efforts to educate the public. Some notable points made in the draft include addressing gender inequity where females are nearly twice as likely as men to get infected with HIV and tailoring resources to mobilized regions where the health system may be compromised due to natural disasters, etc. Among the points made, it seems clear that although the prevalence of HIV transmission is declining, there is still a need for resources, health education, and global efforts to end this epidemic.

Structure[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization is a member of the United Nations Development Group.[92]

Membership[edit | edit source]

As of 2020[update], the WHO has 194 member states: all of the member states of the United Nations except for Liechtenstein, plus the Cook Islands and Niue.[93] (A state becomes a full member of WHO by ratifying the treaty known as the Constitution of the World Health Organization.) As of 2013[update], it also had two associate members, Puerto Rico and Tokelau.[94] Several other countries have been granted observer status. Palestine is an observer as a "national liberation movement" recognized by the League of Arab States under United Nations Resolution 3118. The Holy See also attends as an observer, as does the Order of Malta.[95] The government of Taiwan was allowed to participate under the designation ‘Chinese Taipei’ as an observer from 2009–2016, but has not been invited again since.[96] In July 2020 the United States officially indicated its intent to withdraw, to take effect 6 July 2021.[97]

WHO member states appoint delegations to the World Health Assembly, the WHO's supreme decision-making body. All UN member states are eligible for WHO membership, and, according to the WHO website, "other countries may be admitted as members when their application has been approved by a simple majority vote of the World Health Assembly".[93] The World Health Assembly is attended by delegations from all member states, and determines the policies of the organization.

The executive board is composed of members technically qualified in health and gives effect to the decisions and policies of the World Health Assembly. In addition, the UN observer organizations International Committee of the Red Cross and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies have entered into "official relations" with WHO and are invited as observers. In the World Health Assembly, they are seated alongside the other NGOs.[95]

World Health Assembly and Executive Board[edit | edit source]

The World Health Assembly (WHA) is the legislative and supreme body of WHO. Based in Geneva, it typically meets yearly in May. It appoints the Director-General every five years and votes on matters of policy and finance of WHO, including the proposed budget. It also reviews reports of the Executive Board and decides whether there are areas of work requiring further examination. The Assembly elects 34 members, technically qualified in the field of health, to the Executive Board for three-year terms. The main functions of the Board are to carry out the decisions and policies of the Assembly, to advise it and to facilitate its work.[98] As of May 2020, the chairman of the executive board is Dr. Harsh Vardhan.[99]

Director-General[edit | edit source]

The head of the organization is the Director-General, elected by the World Health Assembly.[100] The term lasts for 5 years, and Directors-General are typically appointed in May, when the Assembly meets. The current Director-General is Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who was appointed on 1 July 2017.[101]

Global institutions[edit | edit source]

Apart from regional, country and liaison offices, the World Health Assembly has also established other institutions for promoting and carrying on research.[102]

Regional offices[edit | edit source]

The regional divisions of WHO were created between 1949 and 1952, and are based on article 44 of the WHO's constitution, which allowed the WHO to "establish a [single] regional organization to meet the special needs of [each defined] area". Many decisions are made at regional level, including important discussions over WHO's budget, and in deciding the members of the next assembly, which are designated by the regions.[104]

Each region has a regional committee, which generally meets once a year, normally in the autumn. Representatives attend from each member or associative member in each region, including those states that are not full members. For example, Palestine attends meetings of the Eastern Mediterranean Regional office. Each region also has a regional office.[104] Each regional office is headed by a director, who is elected by the Regional Committee. The Board must approve such appointments, although as of 2004, it had never over-ruled the preference of a regional committee. The exact role of the board in the process has been a subject of debate, but the practical effect has always been small.[104] Since 1999, Regional directors serve for a once-renewable five-year term, and typically take their position on 1 February.[105]

Each regional committee of the WHO consists of all the Health Department heads, in all the governments of the countries that constitute the Region. Aside from electing the regional director, the regional committee is also in charge of setting the guidelines for the implementation, within the region, of the health and other policies adopted by the World Health Assembly. The regional committee also serves as a progress review board for the actions of WHO within the Region.[citation needed]

The regional director is effectively the head of WHO for his or her region. The RD manages and/or supervises a staff of health and other experts at the regional offices and in specialized centres. The RD is also the direct supervising authority – concomitantly with the WHO Director-General – of all the heads of WHO country offices, known as WHO Representatives, within the region.[citation needed]

| Region | Headquarters | Notes | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | Brazzaville, Republic of the Congo | AFRO includes most of Africa, with the exception of Egypt, Sudan, Djibouti, Tunisia, Libya, Somalia and Morocco (all fall under EMRO).[106] The Regional Director is Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, a Botswanan national. (Tenure: – present).[107] | AFRO Archived 4 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine |

| Europe | Copenhagen, Denmark | EURO includes all of Europe (except Liechtenstein) Israel, and all of the former USSR.[108] The Regional Director is Dr. Zsuzsanna Jakab, a Hungarian national (Tenure: 2010 – present).[109] | EURO Archived 21 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine |

| South-East Asia | New Delhi, India | North Korea is served by SEARO.[110] The Regional Director is Dr. Poonam Khetrapal Singh, an Indian national (Tenure: 2014 – present).[111] | SEARO Archived 19 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine |

| Eastern Mediterranean | Cairo, Egypt | The Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office serves the countries of Africa that are not included in AFRO, as well as all countries in the Middle East except for Israel. Pakistan is served by EMRO.[112] The Regional Director is Dr. Ahmed Al-Mandhari, an Omani national (Tenure: 2018 – present).[113] | EMRO Archived 28 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine |

| Western Pacific | Manila, the Philippines | WPRO covers all the Asian countries not served by SEARO and EMRO, and all the countries in Oceania. South Korea is served by WPRO.[114] The Regional Director is Dr. Shin Young-soo, a South Korean national (Tenure: 2009 – present).[115] | WPRO Archived 13 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine |

| The Americas | Washington, D.C., United States | Also known as the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), and covers the Americas.[116] The WHO Regional Director is Dr. Carissa F. Etienne, a Dominican national (Tenure: 2013 – present).[117] | AMRO Archived 7 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine |

Employees[edit | edit source]

The WHO employs 7,000 people in 149 countries and regions to carry out its principles.[118] In support of the principle of a tobacco-free work environment, the WHO does not recruit cigarette smokers.[119] The organization has previously instigated the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2003.[120]

Goodwill Ambassadors[edit | edit source]

The WHO operates "Goodwill Ambassadors"; members of the arts, sports, or other fields of public life aimed at drawing attention to WHO's initiatives and projects. There are currently five Goodwill Ambassadors (Jet Li, Nancy Brinker, Peng Liyuan, Yohei Sasakawa and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra) and a further ambassador associated with a partnership project (Craig David).[121]

Country and liaison offices[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization operates 150 country offices in six different regions.[122] It also operates several liaison offices, including those with the European Union, United Nations and a single office covering the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. It also operates the International Agency for Research on Cancer in Lyon, France, and the WHO Centre for Health Development in Kobe, Japan.[123] Additional offices include those in Pristina; the West Bank and Gaza; the US-Mexico Border Field Office in El Paso; the Office of the Caribbean Program Coordination in Barbados; and the Northern Micronesia office.[124] There will generally be one WHO country office in the capital, occasionally accompanied by satellite-offices in the provinces or sub-regions of the country in question.

The country office is headed by a WHO Representative (WR). As of 2010[update], the only WHO Representative outside Europe to be a national of that country was for the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya ("Libya"); all other staff were international. WHO Representatives in the Region termed the Americas are referred to as PAHO/WHO Representatives. In Europe, WHO Representatives also serve as Head of Country Office, and are nationals with the exception of Serbia; there are also Heads of Country Office in Albania, the Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan.[124] The WR is member of the UN system country team which is coordinated by the UN System Resident Coordinator.

The country office consists of the WR, and several health and other experts, both foreign and local, as well as the necessary support staff.[122] The main functions of WHO country offices include being the primary adviser of that country's government in matters of health and pharmaceutical policies.[125]

Financing and partnerships[edit | edit source]

Present[edit | edit source]

The WHO is financed by contributions from member states and outside donors. As of 2020, the biggest contributor is the United States, which gives over $400 million annually.[126] U.S. contributions to the WHO are funded through the U.S. State Department’s account for Contributions to International Organizations (CIO). In 2018 the largest contributors ($150+ each) were the United States, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, United Kingdom, Germany and GAVI Alliance.[127]

In April 2020, U.S. President Donald Trump, supported by a group of members of his party,[128] announced that his administration would halt funding to the WHO.[129] Funds previously earmarked for the WHO were to be held for 60–90 days pending an investigation into WHO's handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in respect to the organization's purported relationship with China.[130] The announcement was immediately criticized by world leaders including António Guterres, the secretary general of the United Nations; Heiko Maas, the German foreign minister; and Moussa Faki Mahamat, African Union chairman.[126]

Past[edit | edit source]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the WHO's work involved increasing collaboration with external bodies.[131] As of 2002[update], a total of 473 non-governmental organizations (NGO) had some form of partnership with WHO. There were 189 partnerships with international NGOs in formal "official relations" – the rest being considered informal in character.[132] Partners include the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation[133] and the Rockefeller Foundation.[134]

As of 2012[update], the largest annual assessed contributions from member states came from the United States ($110 million), Japan ($58 million), Germany ($37 million), United Kingdom ($31 million) and France ($31 million).[135] The combined 2012–2013 budget proposed a total expenditure of $3,959 million, of which $944 million (24%) will come from assessed contributions. This represented a significant fall in outlay compared to the previous 2009–2010 budget, adjusting to take account of previous underspends. Assessed contributions were kept the same. Voluntary contributions will account for $3,015 million (76%), of which $800 million is regarded as highly or moderately flexible funding, with the remainder tied to particular programmes or objectives.[136]

Controversies[edit | edit source]

Roman Catholic Church and AIDS[edit | edit source]

In 2003, the WHO denounced the Roman Curia's health department's opposition to the use of condoms, saying: "These incorrect statements about condoms and HIV are dangerous when we are facing a global pandemic which has already killed more than 20 million people, and currently affects at least 42 million."[137] As of 2009[update], the Catholic Church remains opposed to increasing the use of contraception to combat HIV/AIDS.[138] At the time, the World Health Assembly President, Guyana's Health Minister Leslie Ramsammy, condemned Pope Benedict's opposition to contraception, saying he was trying to "create confusion" and "impede" proven strategies in the battle against the disease.[139]

2009 swine flu pandemic[edit | edit source]

In 2007, the WHO organized work on pandemic influenza vaccine development through clinical trials in collaboration with many experts and health officials.[140] A pandemic involving the H1N1 influenza virus was declared by the then Director-General Margaret Chan in April 2009.[141] Margret Chan declared in 2010 that the H1N1 has moved into the post-pandemic period.[142]

By the post-pandemic period critics claimed the WHO had exaggerated the danger, spreading "fear and confusion" rather than "immediate information".[143] Industry experts countered that the 2009 pandemic had led to "unprecedented collaboration between global health authorities, scientists and manufacturers, resulting in the most comprehensive pandemic response ever undertaken, with a number of vaccines approved for use three months after the pandemic declaration. This response was only possible because of the extensive preparations undertaken during the last decade".[144]

2013–2016 Ebola outbreak and reform efforts[edit | edit source]

Following the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the organization was heavily criticized for its bureaucracy, insufficient financing, regional structure, and staffing profile.[145]

An internal WHO report on the Ebola response pointed to underfunding and the lack of "core capacity" in health systems in developing countries as the primary weaknesses of the existing system. At the annual World Health Assembly in 2015, Director-General Margaret Chan announced a $100 million Contingency Fund for rapid response to future emergencies,[146][147] of which it had received $26.9 million by April 2016 (for 2017 disbursement). WHO has budgeted an additional $494 million for its Health Emergencies Programme in 2016–17, for which it had received $140 million by April 2016.[148]

The program was aimed at rebuilding WHO capacity for direct action, which critics said had been lost due to budget cuts in the previous decade that had left the organization in an advisory role dependent on member states for on-the-ground activities. In comparison, billions of dollars have been spent by developed countries on the 2013–2016 Ebola epidemic and 2015–16 Zika epidemic.[149]

FCTC implementation database[edit | edit source]

The WHO has a Framework Convention on Tobacco implementation database which is one of the few mechanisms to help enforce compliance with the FCTC.[150] However, there have been reports of numerous discrepancies between it and national implementation reports on which it was built. As researchers Hoffman and Rizvi report "As of July 4, 2012, 361 (32·7%) of 1104 countries' responses were misreported: 33 (3·0%) were clear errors (e.g., database indicated 'yes' when report indicated 'no'), 270 (24·5%) were missing despite countries having submitted responses, and 58 (5·3%) were, in our opinion, misinterpreted by WHO staff".[151]

IARC controversies[edit | edit source]

The WHO sub-department, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), has been criticized for the way it analyses the tendency of certain substances and activities to cause cancer and for having a politically motivated bias when it selects studies for its analysis. Ed Yong, a British science journalist, has criticized the agency and its "confusing" category system for misleading the public.[152] Marcel Kuntz, a French director of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, criticized the agency for its classification of potentially carcinogenic substances. He claimed that this classification did not take into account the extent of exposure: for example, red meat is qualified as probably carcinogenic, but the quantity of consumed red meat at which it could become dangerous is not specified.[153]

Controversies have erupted multiple times when the IARC has classified many things as Class 2a (probable carcinogens) or 2b (possible carcinogen), including cell phone signals, glyphosate, drinking hot beverages, and working as a barber.[154]

Taiwanese membership and participation[edit | edit source]

Between 2009 and 2016 Taiwan was allowed to attend WHO meetings and events as an observer but was forced to stop due to renewed pressure from China.[155]

Political pressure from China has led to Taiwan being barred from membership of the WHO and other UN-affiliated organizations, and in 2017 to 2020 the WHO refused to allow Taiwanese delegates to attend the WHO annual assembly.[156] According to Taiwanese publication The News Lens, on multiple occasions Taiwanese journalists have been denied access to report on the assembly.[157]

In May 2018, the WHO denied access to its annual assembly by Taiwanese media, reportedly due to demands from China.[158] Later in May 172 members of the United States House of Representatives wrote to the Director-General of the World Health Organization to argue for Taiwan's inclusion as an observer at the WHA.[159] The United States, Japan, Germany, and Australia all support Taiwan's inclusion in WHO.[160]

Pressure to allow Taiwan to participate in WHO increased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic with Taiwan's exclusion from emergency meetings concerning the outbreak bringing a rare united front from Taiwan's diverse political parties. Taiwan's main opposition party, the KMT, expressed their anger at being excluded arguing that disease respects neither politics nor geography. China once again dismissed concerns over Taiwanese inclusion with the Foreign Minister claiming that no-one cares more about the health and wellbeing of the Taiwanese people than China's central government.[161] During the outbreak Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau[162] voiced his support for Taiwan's participation in WHO, as did Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.[155] In January 2020 the European Union, a WHO observer, backed Taiwan's participation in WHO meetings related to the coronavirus pandemic as well as their general participation.[163]

Travel expenses[edit | edit source]

According to The Associated Press, the WHO routinely spends about $200 million a year on travel expenses, more than it spends to tackle mental health problems, HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria combined. In 2016, Margaret Chan, Director-General of WHO from January 2007 to June 2017,[164] stayed in a $1000-per-night hotel room while visiting West Africa.[165]

Robert Mugabe's role as a goodwill ambassador[edit | edit source]

On 21 October 2017, the Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus appointed former Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe as a WHO Goodwill Ambassador to help promote the fight against non-communicable diseases. The appointment address praised Mugabe for his commitment to public health in Zimbabwe.

The appointment attracted widespread condemnation and criticism in WHO member states and international organizations due to Robert Mugabe's poor record on human rights and presiding over a decline in Zimbabwe's public health.[166][167] Due to the outcry, the following day the appointment was revoked.[168]

2019–20 COVID-19 pandemic[edit | edit source]

The WHO faced criticism from the United States' Trump administration while "guid[ing] the world in how to tackle the deadly" COVID-19 pandemic.[169] The WHO created an Incident Management Support Team on 1 January 2020, one day after Chinese health authorities notified the organization of a cluster of pneumonia cases of unknown etiology.[169][170][171] On 5 January the WHO notified all member states of the outbreak,[172] and in subsequent days provided guidance to all countries on how to respond,[172] and confirmed the first infection outside China.[173] The organization warned of limited human-to-human transmission on 14 January, and confirmed human-to-human transmission one week later.[174][175][176] On 30 January the WHO declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern,[177][178] considered a "call to action" and "last resort" measure for the international community.[179] The WHO's recommendations were followed by many countries including Germany, Singapore and South Korea, but not by the United States.[169] The WHO subsequently established a program to deliver testing, protective, and medical supplies to low-income countries to help them manage the crisis.[169]

While organizing the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic and overseeing "more than 35 emergency operations" for cholera, measles and other epidemics internationally,[169] the WHO has been criticized for praising China's public health response to the crisis while seeking to maintain a "diplomatic balancing act" between China and the United States.[171][180][181][182] Commentators including John Mackenzie of the WHO's emergency committee and Anne Schuchat of the US CDC have stated that China's official tally of cases and deaths may be an underestimation. David Heymann, professor of infectious disease epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said in response that "China has been very transparent and open in sharing its data... and they opened up all of their files with the WHO."[183]

Opposition from the Trump Administration[edit | edit source]

On 14 April 2020, United States President Donald Trump pledged to halt United States funding to the WHO while reviewing its role in "severely mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus."[184] The United States had paid half of its annual assessed fees to the WHO as of 31 March 2020; it would ordinarily pay its remaining fees in September 2020.[185] World leaders and health experts largely condemned President Trump's announcement, which came amid criticism of his response to the outbreak in the United States.[186] WHO called the announcement "regrettable" and defended its actions in alerting the world to the emergence of COVID-19.[187] Trump critics also said that such a suspension would be illegal, though legal experts speaking to Politifact said its legality could depend on the particular way in which the suspension was executed.[185] On 8 May 2020, the United States blocked a vote on a U.N. Security Council resolution aimed at promoting nonviolent international cooperation during the pandemic, and mentioning the WHO.[188] On 18 May 2020, Trump threatened to permanently terminate all American funding of WHO and consider ending U.S. membership.[189] On 29 May 2020, President Trump announced plans to withdraw the U.S. from the WHO,[190] though it was unclear whether he had the authority to do so.[191] On 7 July 2020, President Trump formally notified the UN of his intent to withdraw the United States from the WHO.[192]

Traditional medicine[edit | edit source]

WHO has been moving toward acceptance and integration of traditional medicine and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). In 2022, the new International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, ICD-11, will attempt to enable classifications from traditional medicine to be integrated with classifications from evidence-based medicine. Though Chinese authorities have pushed for the change, this and other support of the WHO for traditional medicine has been criticized by the medical and scientific community, due to lack of evidence and the risk of endangering wildlife hunted for traditional remedies.[193][194][195] A WHO spokesman said that the inclusion was "not an endorsement of the scientific validity of any Traditional Medicine practice or the efficacy of any Traditional Medicine intervention."[194]

World headquarters[edit | edit source]

The seat of the organization is in Geneva, Switzerland. It was designed by Swiss architect Jean Tschumi and inaugurated in 1966.[196] In 2017, the organization launched an international competition to redesign and extend its headquarters.[197]

Early views[edit | edit source]

-

On a 1966 stamp of the German Democratic Republic

-

Stairwell, 1969

-

Internal courtyard, 1969

-

Reflecting pool, 1969

-

Exterior, 1969

Views 2013[edit | edit source]

-

From Southwest

-

Entrance hall

-

Main conference room

See also[edit | edit source]

- Global health

- Global Mental Health

- Healthy city / Alliance for Healthy Cities, an international alliance

- Health promotion

- Health Sciences Online, virtual learning resources

- High 5s Project, a patient safety collaboration

- International Health Partnership

- International Labour Organization

- List of most polluted cities in the world by particulate matter concentration

- Open Learning for Development, virtual learning resources

- The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

- Sustainable development

- Timeline of global health

- Tropical disease

- United Nations Interagency Task Force on the Prevention and Control of NCDs

- WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- WHO Guidelines for drinking-water quality

- WHO Pesticide Evaluation Scheme

- World Hearing Day

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Jan 24, Published; 2019 (24 January 2019). "The U.S. Government and the World Health Organization". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "WHO Constitution, BASIC DOCUMENTS, Forty-ninth edition" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2020.

- ↑ "CONSTITUTION OF THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION" (PDF). Basic Documents. World Health Organization. Forty-fifth edition, Supplement: 20. October 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ "History". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ↑ "Milestones for health over 70 years". www.euro.who.int. 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ↑ "World Health Organization | History, Organization, & Definition of Health". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ↑ "What we do". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ↑ "WHO | World health report 2013: Research for universal health coverage". WHO. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ↑ "Dr Tedros takes office as WHO Director-General". World Health Organization. 1 July 2017. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "European governments working with U.S. on plans to overhaul WHO, health official says". The Globe and Mail Inc. Reuters. 19 June 2020. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ↑ Howard-Jones, Norman (1974). The scientific background of the International Sanitary Conferences, 1851–1938 (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ McCarthy, Michael (October 2002). "A brief history of the World Health Organization". The Lancet. 360 (9340): 1111–1112. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11244-x. PMID 12387972.

- ↑ Sze Szeming Papers, 1945–2014, UA.90.F14.1 Archived 1 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, University Archives, Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "World Health Organization". The British Medical Journal. 2 (4570): 302–303. 7 August 1948. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4570.302. JSTOR 25364565. PMC 1614381.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "The Move towards a New Health Organization: International Health Conference" (PDF). Chronicle of the World Health Organization. 1 (1–2): 6–11. 1947. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- ↑ Shimkin, Michael B. (27 September 1946). "The World Health Organization". Science. 104 (2700): 281–283. Bibcode:1946Sci...104..281S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1016.3166. doi:10.1126/science.104.2700.281. JSTOR 1674843. PMID 17810349.

- ↑ J, Charles (1968). "Origins, history, and achievements of the World Health Organization". BMJ. 2 (5600): 293–296. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5600.293. PMC 1985854. PMID 4869199.

- ↑ "World Health Organization Philippines". WHO. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 "WHO at 60" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ Fenner, Frank (1988). "Development of the Global Smallpox Eradication Programme". Smallpox and Its Eradication. History of International Public Health. Vol. 6. Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 366–418. ISBN 978-92-4-156110-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|archive-url=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (help) - ↑ "Construction of the main WHO building". who.int. WHO. 2016. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ Zikmund, Vladimír (March 2010). "Karel Raška and Smallpox" (PDF). Central European Journal of Public Health. 18 (1): 55–56. PMID 20586232. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ Holland, Walter W. (March 2010). "Karel Raška – The Development of Modern Epidemiology. The role of the IEA" (PDF). Central European Journal of Public Health. 18 (1): 57–60. PMID 20586233. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ Orenstein, Walter A.; Plotkin, Stanley A. (1999). Vaccines. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co. ISBN 978-0-7216-7443-8. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Flight, Colette (17 February 2011). "Smallpox: Eradicating the Scourge". BBC History. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ "Anniversary of smallpox eradication". WHO Media Centre. 18 June 2010. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "World Health Day: Safe Motherhood" (PDF). WHO. 7 April 1998. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ Xuequan, Mu, ed. (4 October 2006). "Zimbabwe launches world's 1st AIDS training package". chinaview.cn. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 5 October 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ "Constitution of the World Health Organization" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ↑ "The role of WHO in public health". WHO. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ Hoffman S.J.; Røttingen J-A. (2012). "Assessing Implementation Mechanisms for an International Agreement on Research and Development for Health Products". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 90 (12): 854–863. doi:10.2471/BLT.12.109827. PMC 3506410. PMID 23226898.

- ↑ "Civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS)". who.int. Archived from the original on 4 May 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 33.8 33.9 "Programme Budget, 2012–2013" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ "Global health sector strategy on HIV/AIDS 2011–2015" (PDF). WHO. 2011. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ "Global health sector strategy on HIV/AIDS 2011–2015" (PDF). WHO. 2011. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ↑ "Malaria Fact Sheet". WHO Media Centre. WHO. April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "Tuberculosis Fact Sheet". WHO work mediacenter. WHO. April 2012. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ "WHO". Archived from the original on 28 April 2005. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- ↑ "Poliomyelitis Fact Sheet". WHO Media Centre. WHO. October 2011. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Violence and Injury Prevention". Who.int. Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "Entre Nous". euro.who.int. WHO/Europe. OCLC 782375711. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017.

- ↑ "An estimated 12.6 million deaths each year are attributable to unhealthy environments". who.int. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ "1 WHO's First Global Conference on Air Pollution and Health Improving air quality, combatting climate change – saving lives" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ "Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction". WHO. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "Tobacco". WHO. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ "Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health". WHO. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ Becker, Rachel (25 April 2019). "The WHO's new screen time limits aren't really about screens". The Verge. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- ↑ WHO. Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020 Archived 10 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care". WHO. 11 August 2011. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "Essential trauma care project". WHO. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "Safe Surgery Saves Lives". WHO. 17 June 2011. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "Safe Surgery Saves Lives". WHO. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "UN: Spread of polio now an world health emergency" (Press release). London: Mindspark Interactkookve Network, Inc. AP News. 5 May 2014. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ Gladstone, Rick (5 May 2014). "Polio Spreading at Alarming Rates, World Health Organization Declares". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ Kelland, Kate; Onuah, Felix (8 August 2014). "WHO declares Ebola an international health emergency" (Press release). London/Lagos. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ "Family of International Classifications: definition, scope and purpose" (PDF). WHO. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes". WHO. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "About the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control". WHO. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel" (PDF). WHO. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ Hoffman S.J., Lavis J.N., Bennett S. (2009). "The Use of Research Evidence in Two International Organizations' Recommendations about Health Systems". Healthcare Policy. 5 (1): 66–86. doi:10.12927/hcpol.2009.21005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "International Health Partnership". IHP+. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization". WHO. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy: Seventh Report". WHO Press Office. WHO. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Study Group on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice". 27 March 2012. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research". WHO. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ "HINARI Access to Research in Health Programme". Who.int. 13 October 2011. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 "Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV 2016–2021" (PDF). apps.who.int. World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ↑ "Strategic and Technical Advisory Committee meets on HIV priorities". Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ Chestnov, Oleg (January 2014). "Forward" Archived 12 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, in Connor, Stephen and Sepulveda Bermedo, Maria Cecilia (editors), Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life, Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance and World Health Organization, p. 3. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ↑ Connor SR, Gwyther E (2018). "The Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance". J Pain Symptom Manage. 55 (2): S112–S116. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.020. PMID 28797861.

- ↑ "World Health Day – 7 April". WHO. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "Millennium Development Goals". WHO. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "Accelerating progress towards the health-related Millennium Development Goals" (PDF). WHO. 2010. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "WHO World Health Survey". WHO. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE)". WHO. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "Country Health Policy Process". Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ↑ "Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies". WHO. 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Handbook on monitoring and evaluation of human resources for health". WHO. 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Global Health Observatory". Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ↑ See respectively:*"Mental Health: WHO-AIMS". WHO. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012. *"WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment" (PDF). 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012. *"Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA)". WHO. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "What is HMN?". Health Metrics Network. WHO. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Evidence-Informed Policy Network". WHO. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Policy on Research for Health". Pan American Health Organization. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "Mental health information at your fingertips – WHO launches the MiNDbank". Who.int. 10 December 2013. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ "The World Health Report". WHO. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Bulletin of the World Health Organization". WHO. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal". WHO. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Human Resources for Health". BioMed Central. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública". Pan American Health Organization. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Global health sector strategy on HIV, 2016–2021". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ↑ "UNDG Members". Undg.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Countries". WHO. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ "Appendix 1, Members of the World Health Organization (at 31 May 2009)" (PDF). World Health Organization. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Burci, Gian Luca; Vignes, Claude-Henri (2004). World Health Organization. Kluwer Law International. ISBN 978-90-411-2273-5. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ Timsit, Anabel; Hui, Mary (16 May 2020). "Taiwan's status could disrupt the most important global health meeting of this pandemic". Quartz. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ "Trump administration moves to formally withdraw US from WHO". The Hill. 7 July 2020. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ↑ "Governance". World Health Organization. 23 April 2020. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ↑ "WHO: Chairman and Officers of the Executive Board". World Health Organization. 22 May 2020. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ↑ "WHO Governance". WHO. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "World Health Assembly elects Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus as new WHO Director-General". WHO. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ See, generally, Article 18 of the Constitution of the World Health Organization.

- ↑ World Health Assembly (1965), "WHA18.44 Establishment of an International Agency for Research on Cancer", Eighteenth World Health Assembly, Geneva, 4–21 May 1965: part I: resolutions and decisions: annexes, World Health Organization, pp. 26–30, hdl:10665/85780

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Burci & Vignes 2004, pp. 53–57.

- ↑ "A year of change: Reports of the Executive Board on its 102nd and 103rd sessions" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "Regional Office for Africa". WHO. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "AFRO Regional Director Biography | WHO". afro.who.int. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "Regional Office for Europe". WHO. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "EURO Regional Director Biography | WHO". euro.who.int. 11 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "Regional Office for South-East Asia". WHO. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "SEARO Regional Director Biography | WHO". searo.who.int. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "Regional Office for Eastern Mediterranean". WHO. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "EMRO Regional Director Biography | WHO". emro.who.int. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "Regional Office for the Western Pacific". WHO. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "WPRO Regional Director Biography". wpro.who.int. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "Regional Office for the Americas". WHO. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ "AMRO Reigional Director Biography | WHO". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "Employment: who we are". WHO. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ↑ "Employment: who we need". WHO. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ↑ "Framework Convention on Tobacco Control". WHO. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "Goodwill Ambassador". WHO. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 "WHO its people and offices". WHO. 29 March 2012. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ↑ "WHO liaison and other offices". WHO. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 "Detailed information of WHO offices in countries, territories and areas". WHO. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ↑ "WHO Country Office (Hungary)". WHO EURO. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 "Global Criticism for Trump's W.H.O. Cuts Over Coronavirus Response: Live Updates". The New York Times. 15 April 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 15 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ↑ WHO Results Report – Programme Budget 2018–2019 (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ↑ "Backing Trump, U.S. Republicans call for WHO chief to resign". Reuters. 16 April 2020. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020 – via www.reuters.com.

- ↑ "US to halt funding to WHO over coronavirus". BBC News. 15 April 2020. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020 – via www.bbc.com.

- ↑ Smith, David (15 April 2020). "Trump halts World Health Organization funding over coronavirus 'failure'". Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ↑ "WHO's interactions with Civil Society and Nongovernmental Organizations" (PDF). WHO/CSI/2002/WP6. WHO. 2002. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "WHO's interactions with Civil Society and Nongovernmental Organizations" (PDF). WHO/CSI/2002/WP6. WHO. 2002. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "Living Proof Project: Partner Profile". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundations. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "World Health Organization's Alliance for Health Systems and Policy Research". Rockefeller Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "Assessed Contributions payable by Member States and Associate Members – 2012–2013" (PDF). WHO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ "Programme Budget, 2012–2013" (PDF). WHO. pp. 10, 15–16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ↑ "Vatican: condoms don't stop Aids". The Guardian. 9 October 2003. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- ↑ "Pope claims condoms could make African Aids crisis worse". The Guardian. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "World Health Assembly: Pope Benedict "wrong"". Agence France-Presse. 21 March 2009. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "Tables on clinical evaluation of influenza vaccines". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ "WHO declares pandemic of novel H1N1 virus". CIDRAP. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 7 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ↑ WHO admits errors in handling flu pandemic: Agency accused of overplaying danger of the virus as it swept the globe. Archived 11 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine Posted by NBC News

- ↑ Abelina A; et al. (2011). "Lessons from pandemic influenza A(H1N1) The research-based vaccine industry's perspective" (PDF). Vaccine. 29 (6): 1135–1138. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.11.042. PMID 21115061. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2011.

- ↑ Hoffman, SJ; Røttingen, JA (February 2014). "Split WHO in two: strengthening political decision-making and securing independent scientific advice". Public Health Journal. 128 (2): 188–194. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.021. PMID 24434035.

- ↑ "Report of the Review Committee on the Role of the International Health Regulations (2005) in the Ebola Outbreak and Response" (PDF). 13 May 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ Gostin, Lawrence. "WHO Calls For $100 Million Emergency Fund, Doctor 'SWAT Team'". NPR. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Reform of WHO's work in health emergency management / WHO Health Emergencies Programme" (PDF). 5 May 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- ↑ "WHO Aims To Reform Itself But Health Experts Aren't Yet Impressed". NPR. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Hoffman S.J.; Rizvi Z. (2012). "WHO's Undermining Tobacco Control". The Lancet. 380 (9843): 727–728. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61402-0. PMID 22920746. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.