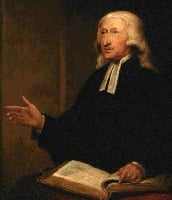

John Wesley

From Nwe

From Nwe

John Wesley (June 17, 1703-March 2, 1791) was the central figure of the eighteenth-century evangelical revival in Great Britain and founder of the Methodist movement. An ordained Anglican clergyman, Wesley adopted unconventional and controversial practices, such as field preaching, to reach factory laborers and newly urbanized masses uprooted from their traditional village culture at the start of the Industrial Revolution. He was not only a gifted evangelist but also a remarkable organizer who created an interlocking system of "societies," annual conferences, and preaching "circuits" (Methodist "connections") which extended his influence throughout England.

Wesley's long and eventful life bridged the Reformation and modern eras of Christianity. His near death as a child in a parish fire, leadership of the "Holy Club" at Oxford, failed missionary labors in Georgia, encounter with the Moravians, conversion at Aldersgate, and controversies surrounding his ministry have long since passed into the lore of Christian history. He rose at four in the morning, lived simply and methodically, and was never idle if he could help it. Although he was not a systematic theologian, Wesley argued in favor of Christian perfection and opposed high Calvinism, notably the doctrine of predestination. His emphasis on practical holiness stimulated a variety of social reform activities, both in Britain and the United States. His theology constituted a counterbalance to the Enlightenment that endorsed humanism and even atheism in the eighteenth century.

Early Life

John Wesley was born on June 17, 1703, the fifteenth of 19 children (eight of whom died in infancy) born to Samuel and Susanna Wesley. Both of his grandfathers were among the nonconformist (Puritan) clergy ejected by the Church of England in 1662. However, Wesley's parents rejected the dissenting tradition and returned to the established church. His father was appointed rector of Epworth, a rough country parish, in 1696. An inflexible Anglican clergyman, frustrated poet and a poor manager of parish funds, Samuel Wesley alienated his rude parishioners who once had him arrested at the church for a debt of thirty pounds. Despite ongoing harassment, Wesley's father served Epworth parish until his death in 1735.

Wesley's mother, Susanna, though deciding at age 13 to join the Church of England, did not leave behind her Puritan austerities. As a consequence Wesley was raised within a household of unremitting discipline. Neither he nor his siblings played with Epworth children and did not attend local school. From the age of five they were home-schooled, being expected to become proficient in Latin and Greek and to have learned major portions of the New Testament by heart. Susanna Wesley examined each child before the midday meal and prior to evening prayers. Children were not allowed to eat between meals and were interviewed singly by their mother one evening each week for the purpose of intensive spiritual instruction.

Apart from his disciplined upbringing, a rectory fire which occurred on February 9, 1709, when Wesley was five years old, left an indelible impression. Sometime after 11:00 P.M., the rectory roof caught on fire. Sparks falling on the children’s beds and cries of "fire" from the street roused the Wesleys who managed to shepherd all their children out of the house except for John who was left stranded on the second floor. With stairs aflame and the roof about to collapse, Wesley was lifted out of the second floor window by a parishioner standing on another man’s shoulders. Wesley later utilized the phrase, "a brand plucked from the burning" (Amos 4:11) to describe the incident. This childhood deliverance subsequently became part of the Wesley legend, attesting to his special destiny and extraordinary work.

Education

Wesley's formal education began in 1714 when at age ten and a half he was sent to Charterhouse School in London. By all accounts, he was a well-prepared student. In 1720, at the age of sixteen, he matriculated at Christ Church, Oxford where, except for a two-year hiatus when he assisted his father, he remained for the next sixteen years. In 1724, Wesley graduated as a Bachelor of Arts and decided to pursue a Master of Arts degree. He was ordained a deacon on September 25, 1725, holy orders being a necessary step toward becoming a fellow and tutor at the university.

At this point, Wesley's scholarly ambitions collided with the first stirrings of his awakening religious consciousness. His mother, on learning of his intention to be ordained, suggested that he "enter upon a serious examination of yourself, that you may know whether you have a reasonable hope of salvation." Wesley subsequently began keeping a daily diary, a practice which he continued for the rest of his life. His early entries included rules and resolutions, his scheme of study, lists of sins and shortcomings, and "general questions" as to his piety all to the end of promoting "holy living." He also began a lifelong obsession with the ordering of time, arising at four in the morning, setting aside times for devotion, and eliminating "all useless employments and knowledge." As Wesley put it in a letter to his older brother, "Leisure and I have taken leave of one another."

In March, 1726, Wesley was unanimously elected a fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford. This carried with it the right to a room at the college and regular salary. While continuing his studies, Wesley taught Greek, lectured on the New Testament and moderated daily disputations at the university. However, a call to ministry intruded upon his academic career. In August, 1727, after taking his master’s degree, Wesley returned to Epworth. His father had requested his assistance in serving the neighboring cure of Wroote. Ordained a priest on September 22, 1728, Wesley served as a parish curate for two years. He returned to Oxford in November, 1729 at the request of the Rector of Lincoln College and to maintain his status as junior Fellow.

The Holy Club

During Wesley's absence, his younger brother Charles (1707-1788) matriculated at Christ College, Oxford. Along with two fellow students, he formed a small club for the purpose of study and the pursuit of a devout Christian life. On Wesley's return, he became the leader of the group which increased somewhat in number and greatly in commitment. Wesley set rules for self-examination. The group met daily from six until nine for prayer, psalms, and reading of the Greek New Testament. They prayed every waking hour for several minutes and each day for a special virtue. Whereas the church's prescribed attendance was only three times a year, they took communion every Sunday. They fasted on Wednesdays and Fridays until three o'clock as was commonly observed in the ancient church. In 1730, the group began the practice of visiting prisoners in jail. They preached, educated, relieved jailed debtors whenever possible, and cared for the sick.

Given the low ebb of spirituality in Oxford at that time, it was not surprising that Wesley's group provoked a negative reaction. They were considered to be religious "enthusiasts" which in the context of the time meant religious fanatics. University wits styled them the "Holy Club," a title of derision. Currents of opposition became a furor following the mental breakdown and death of a group member, William Morgan. In response to the charge that "rigorous fasting" had hastened his death, Wesley noted that Morgan had left off fasting a year and a half since. In the same letter, which was widely circulated, Wesley referred to the name "Methodist" which "some of our neighbors are pleased to compliment us."[1] That name was used by an anonymous author in a published pamphlet (1733) describing Wesley and his group, "The Oxford Methodists."

For all of his outward piety, Wesley sought to cultivate his inner holiness or at least his sincerity as evidence of being a true Christian. A list of "General Questions" which he developed in 1730 evolved into an elaborate grid by 1734 in which he recorded his daily activities hour-by-hour, resolutions he had broken or kept, and ranked his hourly "temper of devotion" on a scale of 1 to 9. Wesley also regarded the contempt with which he and his group were held to be a mark of a true Christian. As he put it in a letter to his father, "Till he be thus contemned, no man is in a state of salvation."

Nevertheless, Wesley was reaching a point of transition. In October, 1734, his aged father asked that he take over the Epworth parish. Wesley declined, stating that he "must stay in Oxford." Only there, he said, could one "obtain the right company, conditions, and ability to pursue a holy discipline – not in bucolic, barbarous Epworth." Ironically, within a few months of turning down Epworth, Wesley and his brother Charles set sail for the more bucolic and barbarous colony of Georgia.

Missionary Labors

James Oglethorpe founded the colony of Georgia along the American southern seaboard in 1733 as a haven for imprisoned debtors, needy families, and persecuted European Protestants. A renowned soldier and Member of Parliament, Oglethorpe led a commission which exposed the horrors of debtor prisons and resulted in the release of more than ten thousand prisoners. However, this created the problem of how to cope with so many homeless, penniless persons let loose in English society. Oglethorpe proposed to solve this by setting up the colony of Georgia as a bulwark against Spanish expansion from the South. He obtained funds, gained a charter, and won the support of the native Creek and Cherokee tribes, several representatives of which accompanied him back to England to great acclaim.

Wesley saw the representative tribesmen in Oxford and resolved to missionize the American Indians. Undoubtedly, disillusionment with Oxford played a part in this decision, and in a letter to one of the colony's promoters, Wesley likened his role to that of Paul, turning from the 'Jews' to the 'Gentiles'. Nevertheless, Wesley's "chief motive" for becoming a missionary was "the hope of saving my own soul." He hoped "to learn the true sense of the gospel of Christ by preaching it to the heathen." Although he persuaded his brother Charles and two other members of the Holy Club to accompany him, Wesley had only limited opportunities to missionize tribal peoples. Instead, he became the designated minister of the colony.

On the passage to America, Wesley and company continued their Holy Club practices: private prayers at 4 A.M., frequent services, readings and exhortations which were resented by passengers. Twenty-six Moravians, refugees from central Europe, also were on board. Wesley was impressed by the "great seriousness of their behavior," by the "servile offices" they performed for other passengers, and by their fearlessness. Wesley reported that in the midst of a psalm, with which they began their service, "the sea broke over, split the mainsail in pieces, covered the ship, and poured in between the decks …" According to Wesley, "A terrible screaming began among the English," while "The Germans calmly sung on." Wesley subsequently went among their "crying, trembling neighbors," pointing out "the difference in the hour of trial, between him that feareth God, and him that feareth Him not." However, Wesley later came under the scrutiny of the Moravian pastor, Augustus Spangenberg, who questioned whether he had the "witness" of the Spirit "within himself." Seeing that Wesley was surprised and "knew not what to answer," Spangenberg asked, "Do you know Jesus Christ?" Wesley replied, "I know he is the Saviour of the world." Spangenberg countered, "True … but do you know he has saved you?" Wesley answered, "I hope He has died to save me." Spangenberg pushed further, "Do you know yourself." Wesley said, "I do" but confessed in his diary, "I fear they were vain words."

Wesley labored strenuously but unsuccessfully in Georgia. He conducted services on Sundays at 5 A.M., 11:00 A.M. and 3 P.M. with prayers in-between and children's catechism at 2 P.M. He visited homes of the some seven hundred souls in Savannah daily between 12 and 3 in the afternoon. However, his narrow clericalism and lack of tact further alienated colonists. He insisted, for example, on the total immersion of infants at baptism and famously refused it to a couple who objected. He had the colony doctor confined to the guardroom for shooting game on the Sabbath which aroused widespread indignation as one of the physician's patients suffered a miscarriage while he was held. Wesley's brother Charles had no better success at Frederica, a hundred miles inland, where parishioners fomented a rift between him and Oglethorpe. Charles eventually fell into a nervous fever, then dysentery and was finally sent home as a courier in 1736.

For all his difficulties, it was an unhappy love affair which proved to be Wesley's final undoing. Wesley founded a small society in Savannah, after the pattern of Oxford, for cultivating the religious life. However, Sophy Hopekey, niece and ward of Thomas Causton, the leading merchant and chief magistrate of the colony, became a focus of his attention. She visited the parsonage daily for prayers and French lessons. Though she was fifteen years younger than Wesley, affection developed. There was hand-holding, kisses and discussion of marriage. Wesley went on retreat to find direction. On return, he informed Sophy that if he married at all, it would be after he worked among the Indians. Later, Wesley prepared three lots, 'Marry', 'Think not of it this year', and 'Think of it no more'. On appealing to "the Searcher of hearts," he drew the third. Frustrated by Wesley's delays and diffidence, Hopekey abruptly married another suitor. Wesley subsequently repelled Sophy from communion, asserting she was becoming lax in religious enthusiasm, her offense being a lack of continued attendance at 5 a.m. prayers. At this point, the chief magistrate had Wesley arrested for defamation of character. The grand jury returned ten indictments and Wesley's case dragged on through Autumn, 1737. Clearly, Wesley’s useful ministry in Georgia was at an end. On Christmas Eve, he fled the colony to Charleston from where he set sail for England, never to return.

Conversion

While still bound for England, Wesley wrote in his journal, "I went to America to convert the Indians! But, oh! Who shall convert me?" Wesley would have his answer in a matter of months, and his conversion at Aldersgate ranks with the Apostle Paul and Augustine's as being among the most notable in the history of Christianity. His conversion was a prelude to continued exertions toward personal holiness and a dramatic ministry.

Five days after arriving in England, Wesley met Peter Boehler, a young Moravian pastor, who like Spangenberg in Georgia, questioned whether Wesley possessed saving faith. Wesley, who was convinced "mine is a fair, summer religion," confessed his doubt and questioned whether he should abandon preaching. Boehler answered, "By no means." Wesley then asked, "But what shall I preach?" Boehler replied, "Preach faith until you have it; and then, because you have it, you will preach faith." Wesley took Boehler's advice to heart and began vigorously preaching the doctrine of salvation by faith alone in London churches. However, his exuberant preaching alienated the establishment. By May, 1738, he was banned from nine churches.

Finally, on May 24, Wesley went "very unwillingly" to a Moravian meeting in Aldersgate Street where one was reading Luther's preface to the Epistle to the Romans. As Wesley recalled,

About a quarter before nine, when he was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death."[2]

This was Wesley’s conversion to which he openly testified to all those present. That summer, he paid a visit to the Moravian settlement of Herrnhut in Germany and met Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, its founder.

His Aldersgate conversion is usually understood to have been his experience of justification by faith. So, Wesley wrote, in his letter to "John Smith" several years later, that "from May 24, 1738, 'wherever I was desired to preach, salvation by faith was my only theme'," and stated that it was perhaps because he neither preached nor knew the "pardoning love of God" through justification before that time that "several of the Clergy forbade me their pulpits" before that time.[3] He even wrote, in his letter to his older brother Samuel, that until the time of his conversion he was "not a Christian," i.e., not "one who so believes in Christ as that sin hath no more dominion over him."

It is also true, however, that even after his breakthrough at conversion Wesley still affirmed that "I am not a Christian now" as of January 4, 1739, saying that he does not possess "the fruits of the spirit of Christ" which are "love, peace, joy," and that he has not been faithful to the given grace of forgiveness of sins.[4] Therefore, Wesleyan scholars such as Albert Outler believe that the Aldersgate experience was not the conversion of Wesley but rather merely "one in a series of the turning points in his passage from don to missionary to evangelist."[5] In this view, Wesley just entered the door of faith at Aldersgate, starting to construct a house of holiness as well as justification which was to come later.

Field Preaching

Wesley's experience in being barred from churches in London paralleled that of a younger colleague, George Whitefield (1717-1770). Whitefield, the last to join Wesley's Holy Club at Oxford in 1734, attained fame as the most dynamic and 'enthusiastic' English preacher of the eighteenth century. Unlike the Wesleys, who were of England's gentry, Whitefield was the son of an innkeeper and paid his way through Oxford by carrying out menial duties. In 1738, Whitefield followed Wesley to Georgia with considerably more success. He later became one of the outstanding revivalists of America’s First Great Awakening (1730-1760). However, in 1739, having returned to England, Whitefield likewise found himself barred from London pulpits.

Moving to Bristol, where he was similarly banned, Whitefield began preaching in the open to coal miners. The response was remarkable. Within a few months, thousands were responding. Through this innovation, Whitefield sparked the beginning of what would become England's eighteenth century evangelical revival. Eager to extend the work but also having committed himself to return to Georgia, Whitefield begged Wesley to continue and organize the campaign. Wesley was hesitant. However, on casting lots with his brother Charles, Wesley decided it was God's will that he go. He arrived in Bristol on Saturday, March 31, 1739 and the next day witnessed Whitefield's preaching. Wesley wrote,

I could scarce reconcile myself to this strange way of preaching in the fields, of which he [Whitefield] set me an example on Sunday; having been all my life till very lately so tenacious of every point relating to decency and order, that I should have thought the saving of souls almost a sin if it had not been done in a church.[6]

Nevertheless, the next day Wesley found himself preaching from a rise in a brickyard to a reported three thousand people gathered to hear him.

Most commentators recognize that Wesley's experience at Bristol marked an important transition in his ministry. Previous to this, his overriding concerns had been personal and parochial, that is, focused upon the well-being of his soul and the established church. However, Bristol transformed Wesley into an evangelist whose efforts would now focus on conveying salvation and holiness to the un-churched. Although he had hoped to be a missionary to the Indians, Wesley at age thirty-six, found his calling among the outcast in England. For the next 50 years, Wesley continued the practice of itinerant evangelism, normally preaching three times a day beginning at 5 A.M., and traveled an estimated 250,000 miles mostly by horseback (in old age by carriage) throughout England.

The Rise of Methodism

The Bristol revival afforded Wesley the opportunity to exercise his two great gifts: preaching and organizing. Not allowing revival energies to dissipate, Wesley founded religious societies on Nicholas and Baldwin Streets between March and June, 1739. He also made arrangements to acquire land on the site of the Bristol Horse Fair for what would become the first Methodist meeting house. Returning to London, Wesley continued his revival preaching and made his first visit to South Wales. These early tours launched his itinerant preaching career. They also precipitated his break from the Moravian Brethren who disliked his aggressive evangelism and resented his assumption of leadership. They barred Wesley from preaching in 1740. This split the Fetter Lane Society in London where Wesley had interacted with the Moravians since returning from Georgia. With an urgent need for a London base, Wesley acquired the damaged King’s Foundery which would serve as the headquarters of Methodism until 1778.

The Methodist "connection" emerged in fits and starts. As early as 1739, Wesley hit upon the idea of requiring subscriptions for membership in newly-created societies. This simultaneously addressed pressing financial needs and provided a mechanism for discipline as unworthy or disruptive members had their subscriptions suspended or denied. In 1740, due to the rapidly spreading revival and lack of clergy support, Wesley began the practice of allowing lay preachers. He appointed twenty that year, and by 1744, there were seventy-seven in the field. Wesley, himself, extended his itinerancy to the North and South of England. In 1744, Wesley convened his first Conference which consisted of six Anglican ministers and four lay preachers. It would become the movement’s ruling body. In 1746, Wesley organized geographical circuits for traveling preachers and more stationary superintendents.

Over time, a shifting pattern of societies, circuits, quarterly meetings, annual Conferences, classes, bands, and select societies took shape. At the local level, there were numerous societies of different sizes which were grouped into circuits to which traveling preachers were appointed for two-year periods. Circuit officials met quarterly under a senior traveling preacher or "assistant." Conferences with Wesley, traveling preachers and others were convened annually for the purpose of coordinating doctrine and discipline for the entire connection. Classes of a dozen or so society members under a leader met weekly for spiritual fellowship and guidance. In early years, there were "bands" of the spiritually gifted who consciously pursued perfection. Those who were regarded to have achieved it were grouped in select societies or bands. In 1744, there were 77 such members. There also was a category of penitents which consisted of backsliders.

Apart from the underclass, the Methodist movement afforded opportunities for women. Wesley appointed a number of them to be lay preachers. Others served in related leadership capacities. Methodism also was extra-parochial. That is, participation in United Methodist societies was not limited to members of the Church of England. Membership was open to all who were sincere seekers after salvation. Given its trans-denominationalism, Wesley's insistence that his connection remain within the Anglican fold was only one of several factors which sparked hostility and conflict.

Opposition

Wesley was a controversial figure before the rise of Methodism. However, his itinerancy and work among the underclass aroused widespread opposition and, on occasion, mob violence. Settled ministers resented and actively resisted Wesley's forays into their dioceses. When told by the bishop of Bristol that he had "no business here" and that he was "not commissioned to preach in this diocese," Wesley famously replied, "the world is my parish." Having been ordained a priest, Wesley regarded himself to be "a priest of the Church universal." And having been ordained Fellow of a College, he understood that he was "not limited to any particular cure" but had a "commission to preach the Word of God to any part of the Church of England."

Apart from his itinerancy, the Establishment regarded Wesley as a traitor to his class. Bringing spiritual hope to the masses was considered dangerous in an age when literacy was restricted to the elite. The enlightened of the era also were aghast and frightened by the emotionalism that the underclass exhibited in response to Wesley's preaching. Describing violent reactions at one of his stops, Wesley wrote,

many of those that heard began to call upon God with strong cries and tears. Some sank down, and there remained no strength in them; others exceedingly trembled and quaked; some were torn with a kind of convulsive motion … I have seen many hysterical and epileptic fits; but none of them were like this.[7]

Methodist meetings were frequently disrupted by mobs. These were encouraged by local clergy and sometimes local magistrates. Methodist buildings were ransacked and preachers harassed and beaten. A favorite tactic of Methodist-baiters was to drive oxen into congregations assembled for field-preaching. At Epworth, Wesley was barred from speaking in the church, so he addressed a large crowd, standing on his father’s tombstone. At Wednesbury, mob violence continued for six days prior to Wesley’s arrival. On occasion, Wesley was dragged before local justices but rarely held. Wesley, himself, was fearless in confronting mobs and even converted some of the most vocal ringleaders. In addition, the energy and aggressiveness of opponents often dissipated when they found Wesley to be educated, articulate, and a member of the gentry class.

Nevertheless, fierce opposition against Wesley and his movement persisted until the 1760s.

The Consolidation of Methodism

Wesley's later years were dominated by questions of succession and separation. That is, how would Wesleyan Methodism continue once its powerful central figure was gone and would the movement remain within the orbit of Anglicanism or become independent? Wesley had been concerned about the issue of succession since 1760 when he proposed the creation of a council or committee to succeed him. Later, he decided Methodism required a strong presiding officer and in 1773, designated John William Fletcher, one of the few affiliated Church of England clergy, to be his successor. Unfortunately, Wesley outlived Fletcher. In the end, Wesley put forth a Deed of Declaration on February 27, 1784, which empowered a Conference of one hundred to take over the movement's property and direction after his death.

Wesley consistently stated that he had no intention of separating from the Church of England. However, circumstances in America forced an initial breech. The Wesleyan movement sent two preachers to the colonies in 1769 and two more in 1771. An American Methodist Conference was held in 1774 with membership less than 3,000. By 1784, membership reportedly increased to nearly 13,000 and in 1790, a year before Wesley's death, the number stood at nearly 60,000. Wesley asked the Bishop of London to ordain a preacher for America but was refused. Therefore, in September, 1784, Wesley ordained a superintendent and later seven presbyters with power to administer the sacraments. Although Wesley did not acknowledge it, this was a major step in separating Methodism from the Church of England. The final step came in 1795, four years after Wesley's death, with the Plan of Pacification which formulated measures for the now independent church.

Poverty and Education

Wesley had a profound concern for people's physical as well as spiritual welfare. Holiness had to be lived. Works of kindness were 'works of piety' or 'mercy'; he believed that doing good to others was evidence of inner conviction, outward signs of inner grace. He wanted society to be holy as well as individuals. He saw his charities as imitating Jesus' earthly ministry of healing and helping the needy. Through his charities, he made provision for care of the sick, helped to pioneer the use of electric shock for the treatment of illness, superintended schools and orphanages and spent almost all of what he received for his publications, at least £20,000 on his charities. His charities were limited only by his means. In 1748 he founded Kingswood School in order to educate the children of the growing number of Methodist preachers. The Foundery, which he opened in London in 1738, became the prototype Methodist Mission or Central Hall found in many downtown areas. Religious services were held there alongside a school for children and welfare activities, including loans to assist the poor. Wesley himself died poor.

Theology

"Wesleyan Quadrilateral"

American Methodist scholar Albert Outler argued in his introduction to the 1964 collection John Wesley that Wesley developed his theology by using a method that Outler termed the "Wesleyan Quadrilateral."[8] This method involved scripture, tradition, experience, and reason as four different sources of theological or doctrinal development. Wesley believed, first of all, that the living core of the Christian faith was revealed in "scripture" as the sole foundational source. The centrality of scripture was so important for Wesley that he called himself "a man of one book"—meaning the Bible—although he was a remarkably well-read man of his day. However, doctrine had to be in keeping with Christian orthodox "tradition." So, tradition became in his view the second aspect of the so-called Quadrilateral. Furthermore, believing, as he did, that faith is more than merely an acknowledgment of ideas, Wesley as a practical theologian, contended that a part of the theological method would involve "experiential" faith. In other words, truth would be vivified in personal experience of Christians (overall, not individually), if it were really truth. And every doctrine must be able to be defended "rationally." He did not divorce faith from reason. Tradition, experience, and reason, however, are subject always to scripture, which is primary.

Doctrine of God

Wesley affirmed God's sovereignty. But what was unique about his doctrine of God was that it closely related God's sovereignty to the other divine attributes such as mercy, justice, and wisdom. He located the primary expression of God's sovereignty in the bestowal of mercy rather than in the abstract concept of absolute freedom or self-sufficiency. This helped the notion of sovereignty to be freed from its frequent overtones of absolute predestination and arbitrariness, thus allowing a measure of human free agency. In this way, God's loving and merciful interaction with free and responsible human beings does not detract from his glory. This was what made Wesley's theology different from Calvinism. He was convinced that this understanding of God as sovereign only in the context of mercy and justice is "thoroughly grounded in Scripture."[9]

Original sin and "prevenient grace"

Following the long Christian tradition, Wesley believed that human beings have original sin, which contains two elements: guilt (because they are guilty of Adam's sin) and corrupted nature (because their human nature is corrupted after Adam's sin), and that given this original sin they cannot move themselves towards God, being totally dependent on God's grace. So, Wesley introduced what is called "prevenient grace," saying that it is given to all humans as the first phase of salvation, providing them with the power to respond to or resist the work of God. What is interesting is that when Wesley believed that prevenient grace is "free" and not meritorious at all, given the miserable human condition with original sin, he echoed the classical Protestant tradition. But, when he maintained that prevenient grace is also available to all humans and gives them the power to respond or resist, he differed from that tradition.

Repentance and justification

As a next step in the process of salvation according to Wesley, if human beings respond to God through prevenient grace, they will be led to a recognition of their fallen state, and so to repentance. Then, repentance, or conviction of sin, thus reached, and its fruits or works suitable for repentance become the precondition of justifying faith, i.e., faith that justifies the believer, legally proclaiming that he is no longer guilty of Adam's sin. Wesley's description of justifying faith as preconditioned by repentance and its fruits or works suitable for repentance was another reason why he differed from the classical Reformers such as Luther and Calvin who strongly adhered to the doctrine of justification by faith alone. But, we have to understand that this difference arose because Wesley had a narrower definition of justifying faith than Luther and Calvin. Whereas Luther and Calvin believed justifying faith to include both repentance and trust in God, saying that repentance is also the work of faith, Wesley defined faith as only trust in Christ, separating repentance from it. This narrower definition of justifying faith may have been the reason why Wesley felt that prior to his Aldersgate Street conversion in 1738 he was not a Christian yet, i.e., that prior to that conversion he was not justified yet, while already in the earlier state of repentance.[10]

At conversion, the believer has two important experiences, according to Wesley: justification and new birth. Both happen to the believer instantaneously and simultaneously through justifying grace, but they are distinguishable because they bring forensic and real changes, respectively. Justification brings a forensic change, "imputing" Christ's righteousness to the believer, who is now proclaimed as not guilty of Adam's sin. New birth, by contrast, gives rise to a real change, which is a regeneration from the death of corrupted nature to life, "imparting" Christ's holiness to the believer. However, this does not mark the completion of salvation yet. New birth is just the beginning of the gradual process of sanctification which is to come.

Sanctification

Along with the Reformation emphasis on justification, Wesley wanted to stress the importance of sanctification in his theology. According to him, the gradual process of sanctification continues after the instantaneous moment of justification and new birth marks the beginning of the process. New birth only partially renews the believer. But, gradual sanctification afterwards involves the further impartation of Christ's holiness in the actual life of the believer to overcome the flesh under sanctifying grace. Wesley argued for the possibility of "entire sanctification," i.e., Christian "perfection," in the life of the believer. Wesley's doctrine of perfection was the result of a lifelong preoccupation with personal salvation and holiness. As early as 1733 in a sermon, "The Circumcision of the Heart," Wesley referred to a "habitual disposition of the soul … cleansed from sin" and "so renewed" as to be "perfect as our Father in heaven is perfect."[11] In later writings, Wesley defined perfection as "the pure love of God and our neighbor." However, he noted that it coexists with human "infirmities." Perfection frees people from "voluntary transgressions" but not necessarily from sinful inclinations. He maintained that individuals could have assurance of perfection, akin to a second conversion or instantaneous sanctifying experience, through the testimony of the Spirit. Wesley collected and published such testimonies.

Unfortunately, Wesley's doctrine of perfection led to excesses and controversy during the 1760s when several of its most forceful advocates made claims to the effect that they could not die or the world was ending. Although Wesley disowned some and others disowned him, the episodes reawakened criticism as to Wesleyan "enthusiasm."

Wesley and Arminianism

In 1740, Wesley preached a sermon on "Free Grace" against predestination, a doctrine which taught that God divided humankind into the eternally elect and reprobate prior to creation and that Christ died only for the elect. To Wesley, predestination undermines morality and dishonors God, representing "God as worse than the devil, as both more false, more cruel, and more unjust."[12] George Whitefield, who inclined to Calvinism, asked him not to repeat or publish the sermon, not wanting a dispute. But Wesley published it. This "predestination controversy" led to a split between Wesley and Whitefield in 1741. Although Wesley and Whitefield were soon back on friendly terms and their friendship remained unbroken thereafter, the united evangelical front was severed. Whitefield separated from Wesley and came to head a party commonly referred to as Calvinistic Methodists.

Wesley inclined strongly toward Arminianism which held that Christ died for all humankind. In his answer to the question of what an Arminian is, Wesley defended Arminianism from common misunderstandings, by arguing that, like Calvinism, it affirms both original sin and justification by faith, and explained that there are, however, three points of undeniable difference between Calvinism and Arminianism: 1) that while the former believes absolute predestination, the latter believes only "conditional predestination" depending on human response; 2) that while the former believes that grace is totally irresistible, the latter believes that "although there may be some moments wherein the grace of God acts irresistibly, yet, in general, any man may resist"; and 3) that while the former holds that a true believer cannot fall from grace, the latter holds that a true believer "may fall, not only foully, but finally, so as to perish for ever."[13] In 1778 he began the publication of The Arminian Magazine to preserve the Methodists and to teach that God wills all humans to be saved, and that "lasting peace" can only be secured by understanding that will of God.

Legacy

Wesley's most obvious legacy is the Methodist Church. Consisting now of numerous bodies and offshoots, estimates of worldwide membership vary widely, ranging from 36-75 million. In the United States, Methodism along with various Baptist bodies quickly eclipsed New England Congregationalism and Presbyterianism, becoming the dominant Protestant denominations on the American frontier. Wesley, along with Whitefield, was a pioneer of modern revivalism which continues to be a potent force of Christian renewal worldwide. In addition, through his emphasis on free grace, entire sanctification, and perfection, Wesley is the spiritual father of the Holiness movement, charismatic renewal, and, to a lesser extent, of Pentecostalism.

Through the church, Wesley also influenced society. Methodists, under Wesley's direction, became leaders in many social justice issues of the day, particularly prison reform and abolitionist movements. Women also were given new opportunities. In America, Methodists were leaders in temperance reform and social gospel movements.

The French historian Élie Halévy (1870-1937), in the first volume of his masterpiece, A History of the English People in the Nineteenth Century (1912), described England in 1815, putting forth the "Halévy thesis" that the evangelical revival and, more specifically, Methodism, enabled eighteenth-century England to avoid the political revolutions that unsettled France and the European continent in 1789 and 1848.[14] As he put it, "Methodism was the antidote to Jacobinism." Socialist historians have tended to deny the Halévy thesis. However, there is no denying that Wesley and his fellow laborers provided hope and encouraged discipline among Britain's newly urbanized and industrialized working class.

It may be worth pondering what Wesley's influence would have been, had he been more successful in Georgia. There, Oglethorpe set forth strict but unpopular bans against slavery and rum. Wesley, in fact, aroused resentment among the colonists on his arrival by personally destroying several cases of rum. In part, due to the disarray which resulted from Wesley's failed mission, both bans were overturned during the 1750s. Although temperance reform has a checkered history in America, had Wesley succeeded in sustaining Oglethorpe's ban on slavery, subsequent history may have taken a different trajectory. Wesley wrote his Thoughts Upon Slavery in 1774.[15] By 1792, five editions had been published. Even Wesley's failures are instructive. His lifelong quest for assurance of salvation, for holiness, and his struggles, as described in his journals and reflected in his sermons, have inspired countless Christians. In this regard, Wesley's personal history is an important part of his legacy.

Wesley's ability to influence society was perhaps related to his basic theology, which encouraged Christians to experience a real change of human nature through sanctification in addition to a merely forensic change brought forth through justification that was much emphasized in the classical Reformation tradition. His rather practical yet holiness-oriented theology constituted a counterbalance to the Enlightenment that endorsed humanism and even atheism in the eighteenth century.

Notes

- ↑ John Wesley, The Letters of John Wesley Wesley Center Online. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ↑ Nehemiah Curnock (ed.), The Journal of The Rev. John Wesley, vol. 1 (Kessinger Publishing, 2007), 475-76. “I Felt My Heart Strangely Warmed” Journal of John Wesley, Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ↑ Thomas Jackson, (ed.), The Works of John Wesley, A.M., vol. XII, 3rd ed. (London: John Mason, 1830), 70.

- ↑ Nehemiah Curnock (ed.), The Journal of The Rev. John Wesley, vol. 2 (Kessinger Publishing, 2007), 125.

- ↑ Albert C. Outler (ed.), John Wesley (Oxford University Press, 1964), 52.

- ↑ James M. Buckley, A History of Methodism in the United States, vol. 1 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1898), 88-89.

- ↑ Curnock, vol. 2, 221-222.

- ↑ Outler, 1964.

- ↑ Jackson, vol. X, 211.

- ↑ Colin W. Williams, John Wesley's Theology Today: A Study of the Wesleyan Tradition in the Light of Current Theological Dialogue (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1960), 65.

- ↑ John Wesley, "The Circumcision of the Heart." Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ↑ John Wesley, "Free Grace." Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ↑ John Wesley, "The Question, 'What Is an Arminian?' Answered by a Lover of Free Grace." Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- ↑ Élie Halévy, England in 1815, vol. 1 of A History of the English People in the Nineteenth Century, trans. E.I. Watkin and D.A. Barker (London: Ernest Benn, 1971).

- ↑ John Wesley, "Thoughts Upon Slavery." Retrieved June 30, 2017.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Curnock, Nehemiah (ed.). The Journal of The Rev. John Wesley. 8 volumes. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1172310425

- Jackson, Thomas (ed.). The Works of John Wesley, A.M. 14 vols. 3rd ed. London: John Mason, 1829-1831.

- Outler, Albert C. (ed.). John Wesley. Oxford University Press, 1964. ISBN 0195011929

- Outler, Albert C., and Richard P. Heitzenrater (eds.). John Wesley's Sermons: An Anthology. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1991. ISBN 068720495X

- Wesley, John. A Plain Account of Christian Perfection. Kansas City, MO: Beacon Hill Press, 1966. ISBN 0834101580

Secondary sources

- Buckley, James M. A History of Methodism in the United States. 2 vols. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1898.

- Collins, Kenneth J. The Scripture Way of Salvation: The Heart of John Wesley's Theology. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1997. ISBN 0687009626

- Collins, Kenneth J. A Real Christian: The Life of John Wesley. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1999. ISBN 0687082463

- Halévy, Élie. England in 1815. Vol. 1 of A History of the English People in the Nineteenth Century, Translated by E.I. Watkin and D.A. Barker. London: Ernest Benn, 1971.

- Lindström, Harald. Wesley and Sanctification: A Study in the Doctrine of Salvation. Grand Rapids, MI: Francis Asbury Press, 1980. ISBN 0310750113

- Tomkins, Stephen. John Wesley: A Biography. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B Eerdmans, 2003. ISBN 0802824994

- Whitehead, John. The Life of the Rev. John Wesley, M.A. Boston: Dow & Jackson, 1845.

- Williams, Colin W. John Wesley's Theology Today: A Study of the Wesleyan Tradition in the Light of Current Theological Dialogue. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1960. ISBN 068720531X

External links

All links retrieved August 3, 2022.

- Brycchan Carey. John Wesley as a British abolitionist.

- John Wesley at Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

- Wesley Center Online at Northwest Nazarene University

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:34:36 | 23 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/John_Wesley | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF