Scotland

From Rationalwiki

From Rationalwiki “”We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation.

|

| —Voltaire actually said this.[1] |

Scotland (Scottish Gaelic: Alba) is a mystical country where people wear kilts and blue face paint and shout for FREEDOM!!! against English oppression while charging into battle with their claymores. It exists only in Mel Gibson's imagination.[2]

The real Scotland is a constituent country of the United Kingdom, located just north of England. While Scotland is indeed known for its centuries-long struggle against English rule, the country is more notable today for its socially progressive political scene, its status as a major oil producer, and its recent repudiations of the Scottish independence movement in both a 2014 referendum![]() and the 2024 UK elections. Scotland is a majority non-religious country, with 51.1% of respondents saying they had "no religion" in the 2022 census.[3] It is also the home of haggis,[4][5] golf, the Loch Ness Monster, and unfortunately JK Rowling too. Glasgow, Scotland's largest city, was once dubbed the "Murder Capital of Europe"[6] due to something called "knife crime" (!) which the Scottish government spent decades campaigning against.[7] So don't piss off a Scot. There's a chance they might cut you.

and the 2024 UK elections. Scotland is a majority non-religious country, with 51.1% of respondents saying they had "no religion" in the 2022 census.[3] It is also the home of haggis,[4][5] golf, the Loch Ness Monster, and unfortunately JK Rowling too. Glasgow, Scotland's largest city, was once dubbed the "Murder Capital of Europe"[6] due to something called "knife crime" (!) which the Scottish government spent decades campaigning against.[7] So don't piss off a Scot. There's a chance they might cut you.

The region that is now Scotland famously never submitted to the Roman Empire despite repeated invasions, and after Roman collapse Scotland came under the influence of Gaelic culture and the new Christian religion spread by missionaries from Ireland. Raids by the Vikings sparked a push for unification, which was militarily accomplished by Kenneth MacAlpin. He founded the Kingdom of Scotland in 843 CE. During the Middle Ages, Scotland frequently fought its wealthier and more populous southern neighbor. The most notable of these conflicts were the Wars of Scottish Independence![]() , which lasted from 1296 to 1328 and then 1332 to 1357. This is where we got famous Scottish heroes like William Wallace and King Robert the Bruce as well as the traditional "Auld Alliance" with England's other main enemy, France.

, which lasted from 1296 to 1328 and then 1332 to 1357. This is where we got famous Scottish heroes like William Wallace and King Robert the Bruce as well as the traditional "Auld Alliance" with England's other main enemy, France.

In 1371, Scotland came under the rule of the House of Stuart, which led it through the processes of acquiring land from Norway and enduring the turbulent Protestant Reformation. In 1603, King James VI Stuart became the King of England, uniting the two former enemies under one crown. The Stuart monarchs clashed with the English Parliament, though, and this political conflict saw Scotland dragged into the English Civil War. Despite this, Scotland became more and more integrated with England, and Scotland partnered with England in settling Protestants in the majority Catholic Ireland in an attempt to help subdue it. An economic crisis around the year 1702 sparked interest in full political unification with England, an agenda which was realized with the passage of the Acts of Union in 1707. Scotland and England became a single country, although Scotland still had some degree of autonomy. This remained the case until Scotland's government was reestablished in 1998.

Since then, the Scottish independence movement, headed by the Scottish National Party (SNP), has been a defining issue of Scottish politics. The independence movement's fortunes saw some dramatic ups-and-downs such as: the failure of the 2014 referendum (it's so over), the sudden revival in nationalist sentiment after Brexit (we're so back), and then a 2022 Supreme Court decision against further referendums and the near-annihilation of the SNP from UK-level politics in 2024 (it's never been more over than it is now). At least for the time being, Scotland will remain part of the United Kingdom.

History[edit]

Ancient history[edit]

As far as anyone knows, humans have inhabited Scotland for about 12,000 years, and these ancient peoples dotted the landscape with stone monuments and tombs.[8] Stone is plentiful in the rugged landscape of Scotland, so it was a common building material. Around 2000 BCE, Irish traders introduced bronze to Scotland, and trade flourished between the two regions.[9]

Around the year 900 CE, Celts from continental Europe began migrating into Scotland; they brought a shared culture and their knowledge of iron-working.[9] The Celtic migration was not always peaceful, a fact attested to by the presence of battlefields and early forts. However, they successfully intermingled with the indigenous peoples of Scotland, and their culture became entrenched. The Celts called themselves "Cruithne" (the painted ones) as they wore face paint and dyed their bodies.[9] They would later be called "Picti" (painted) by the Romans. Celtic society was organized into clans led by a single chieftain, and the Celtic class structure placed warriors at the top, priests, bards and merchants in the middle, and artisans, farmers, and slaves at the bottom.[9]

Roman invasions[edit]

The Roman Empire famously invaded the Isle of Britain in 43 CE and occupied what is now England, bloodily suppressing rebellions along the way. Although the Romans didn't immediately expand northwards, they were concerned about raiding from the clans of Scotland (or, as they called it, "Caledonia"). In 79 CE, Roman governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola launched an invasion of Scotland, successfully occupying most of the region until Roman emperor Domitian withdrew some of his forces to confront a threat closer to the imperial core.[10] The Romans withdrew further south and constructed the famous Hadrian's Wall after Emperor Hadrian visited the region in 122 CE and decided that the Roman frontier first needed to be defended if it was to be expanded.[10] Hadrian's successor, Antoninus Pius, decided to push the border further and construct the Antonine Wall in 139 CE, but it was abandoned after his death due to the difficulty of defending it.[11]

As we can see, the Romans succeeded at invading Scotland on multiple occasions and yet declined to establish a permanent presence. Scotland had proven just too expensive to conquer; the Picts were extremely effective at guerrilla warfare, and the mountainous terrain made it difficult for the Romans to counter them.[11] The Scottish landscape seemingly didn't offer enough to justify the effort.

Afterwards, the Romans largely left the Picts alone, but their presence was a threat that compelled the Picts to politically unite.[12] By 306 CE, the Picts had gone on the offensive by launching attacks on Hadrian's Wall.[11] As the Roman Empire weakened elsewhere, it began withdrawing military assets from Britain, leading to further weakness and more Pictish raids. Combined with incursions from the Angles and Saxons from northern Germany, this pressure caused Roman governance in Britain to gradually collapse. The Romans withdrew from Britain completely in 410 CE in order to deal with matters on continental Europe.[10]

Christianity, Vikings, and unification[edit]

Unfortunately, Scottish history at this point is very spotty due to a lack of contemporary records and the proliferation of fakelore throughout the ages. What we do know is this:

After the Roman withdrawal, Scotland was divided into three political groups. The first were the Picts in central Scotland, who divided into a cluster of small lordships and took slaves from those who were captured in war.[13] Further south was the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria, which had spread its territory into southern Scotland. Finally, to the west, there was the Kingdom of Dál Riata![]() , which spread Gaelic language culture into Scotland. The Gaels, as they are known, probably came from Ireland, but the Irish and Scottish Gaelic languages diverged quite significantly.[14]

, which spread Gaelic language culture into Scotland. The Gaels, as they are known, probably came from Ireland, but the Irish and Scottish Gaelic languages diverged quite significantly.[14]

This is the period during which Christianity first came to Scotland. The bishop today known as Saint Ninian is credited with being the first Christian missionary in Scotland, establishing a church and monastery in 397 CE and converting many people.[15] Although it was slow, the conversion of the Scottish peoples to Christianity was evident in the shift in their artistic styles and subjects.[16] The Irish missionary Saint Columba arrived at the Scottish island of Iona in 563 CE, established a monastery, and (according to tradition) played a primary role in completing Scotland's conversion to Christianity.[17] Iona Abbey became a major site of religious pilgrimage and veneration for the Medieval Scots.

From around 793 CE, the Vikings of Scandinavia began raids on Catholic monasteries, as they were wealthy and lightly defended. The religiously important Iona Abbey was hit repeatedly in 795 CE, 802 CE, 806 CE, and 825 CE.[18] The last raid saw it burned down completely, and its relics were dispersed to other locations for safekeeping. The minor islands around Scotland were useful to the Vikings as a series of ports to handle and ship looted goods back to Scandinavia and harbor raiding forces headed to the fertile lands further south.[19] The people of Scotland also lacked the military sophistication to present a major threat to the Viking invaders. Over time, the Norse built up enough of a presence in Scotland to threaten the squabbling petty kingdoms there.

In 839 CE, King Ailpín of the Dal Raita fell in battle against an alliance of Picts right before a large Viking army intervened to take advantage of the madness.[19] The Vikings killed multiple Pictish kings, and Ailpín’s son, Cináed, used the resulting power vacuum to conquer much of the Pictish territories.[19] He is now known to history as Kenneth McAlpin, and his actions resulted in the military unification of Scotland under his kingship.[20] He spent the rest of his reign solidifying his rule against rebels and pretenders, and his dynasty's rule Scotland was secure by his death in 858 CE. He struck terms with the Vikings, allowing them to settle across the northern coast and islands as long as they left the rest of Scotland alone.[21]

The Kingdom of Scotland[edit]

Instability, expansion, and England too[edit]

The late 900s CE were a turbulent time for England, so its kings found it useful to have friendly relations with their northern neighbor. Scotland was thus able to gain some lands diplomatically, and it gained the Brittonic kingdom of Strathclyde by means of royal inheritance.[22] The Scottish kings also consolidated their territory in the north.

Things weren't so hot in terms of political stability. Scotland's monarchy operated according to the system of tanistry, which meant that any male relative of the king could inherit the throne.[23] This created confusion during successions, and a lot of Scottish kings died due to murder at the hands of their successor. King Mac Bethad mac Findláig, for instance, took the throne in 1040 after defeating his predecessor Donnchad mac Crinain (Duncan I) in battle and then killing him.[24] This king is better known by his anglicized name, Macbeth, due to the famous (and almost entirely fictional) play by Shakespeare. Macbeth's real history saw a major war with England over the claims of Duncan I's son, sparking a series of events that led to his violent death in 1057.[24] For Scotland, this was a horrible development, as England had now shown interest in military intervening in Scottish politics.

Afterwards came the greatly important reign of Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim (David I), which began in 1080 and contributed greatly to shaping Scotland as a nation. David brought English Norman settlers into the southern part of Scotland, leading to a major cultural shift that would see Scotland begin to adopt the English language as its primary means of communication.[25] He also established new settlements (including Stirling and Perth), began the minting of Scottish coins, and supported Catholic monasteries in establishing local industries.[25]

David's successor, Malcolm IV, did not have so productive of a reign, as he was forced to make territorial concessions to England in 1157.[26] England had greater wealth and population than Scotland, and its ruling Plantagenet dynasty now controlled vast territories in France. So it was understandable, to us at least, that Malcolm judged that England was not to be fucked with. It was not understandable to the Scottish nobility, who promptly revolted and plunged the rest of Malcolm's reign into civil war.[26] Oh, and they also nicknamed him "Malcolm the Maiden". Ouch.

Things went even worse for Scotland during the reign of Uilleam an Leòmhann (William I the Lion), who supported a rebellion against England in 1173 in the hopes of weakening the threat to the south.[27] Instead, William got himself captured, and he was forced to pay reparations, surrender control of some of his castles, and acknowledge King Henry II of England as his feudal overlord.[27] Not good, William. Not good. Although Scotland wormed its way out of this arrangement during the Third Crusade, the subsequent kings of England never let go of the idea that Scotland should be beneath them.

William the Lion's successor, Alaxandair mac Uilliam (Alexander II), initially saw his reign plagued by his inability to produce a male heir. The nobles of the realm allegedly decided that, if the king died before he had a son, then Lord Robert Bruce of of Annandale would become the new king as his nearest male relative.[28] Or at least, this is what Robert Bruce claimed. Remember that name, by the way. Regardless, it was a near-miss; Alexander II got his son about eight years before his death in 1249. His son, King Alexander III, proved himself an effective king by winning a major war against Norway to seize the Hebrides islands and the Isle of Man in 1266.[29] But within his reign were the seeds of disaster: he married the daughter of England's king Henry III and had to contend with his father-in-law's demands for fealty.[29] Fuckin' in-laws, man. Alexander III also died without a male heir in 1289, creating a crisis that would give England the perfect excuse to intervene.

The wars for independence (FREEDOM!!!)[edit]

Hoping to prevent the outbreak of a civil war after Alexander III's death, Scotland's nobility invited England's king, Edward I "Longshanks", to arbitrate the succession dispute.[30] The hope was that having England's military power behind the chosen king would prevent pretenders from dethroning him. In exchange for picking John Balliol to be king, Edward demanded that Scotland's nobles acknowledge him as having "sovereign lordship of Scotland."[30] He also insisted that King John Balliol pay him homage in London to run his decisions by Edward, which humiliated and infuriated the Scots so much that they deposed Balliol in 1294.[30]

The Scottish nobles understood quite well that England wasn't about to let this slide, so they struck a military and commercial alliance with another English enemy, France, in 1295.[31] Although the Auld Alliance served both countries well for the next few centuries, it didn't stop what was about to happen.

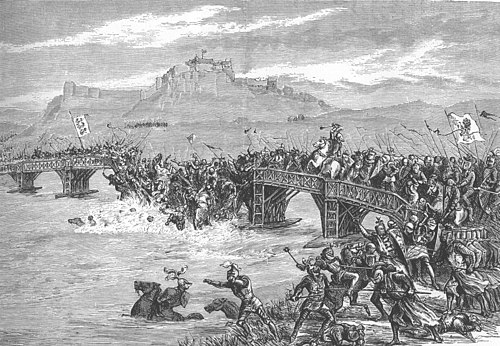

King Edward ordered an invasion of Scotland in 1296, which soon resulted in the wholesale massacre of the city of Berwick. According to 15th century chronicler Walter Bower, English forces spared "no one, whatever the age or sex, and for two days streams of blood flowed from the bodies of the slain … so that mills could be turned round by the flow of their blood."[32] Meanwhile, outlaw William Wallace and his followers massacred an English garrison at Lanarck Castle in retaliation for the unjust execution of his wife.[33] This won him attention from the Scottish people and fury from the English. Andrew of Moray, a Scottish noble rebelling in the north, then had his forces link up with Wallace.[34] Their small army decisively smashed a much larger English force on 11 September, 1297 at the Battle of Stirling Bridge.[35]

This battle was a legendary victory in Scottish memory, but in reality, the English rallied and came back the next year, defeating Wallace in battle and forcing him into exile in France.[33] His return to Scotland in 1305 resulted in his capture, brutal torture, and grisly execution at the hands of the English.[33]

Scotland's cause seemed pretty dead at this point, with much of its nobility pledging allegiance to England. However, Robert Bruce, who claimed the Scottish throne based on his father's allegations from earlier, returned to Scotland from France in 1306.[32] Unfortunately, he fucked up. His blatant murder of John Comyn, a rival claimant to the throne, alienated much of Scotland and resulted in his excommunication by the pope.[32] England declared him to be a mere outlaw, but Bruce had himself crowned king anyway.

What followed was a grueling guerilla campaign in which Bruce took advantage of Scotland's rugged landscape to stage hit-and-run raids on the militarily superior English forces. His power base grew, and by 1314, he had control of much of Scotland.[36] Edward I had also died, leaving his weak-willed son Edward II in charge of the English war effort. 1314 also saw the Battle of Bannockburn, a decisive clash between the two kings that left Bruce victorious and Edward II humiliated.[37] The war didn't end here, but the battle was a major setback for the English. The war ended with a 1328 treaty in which Edward II renounced all claims to lordship over Scotland in exchange for a bribe.[38] Bruce, deprived of his main life's purpose of killing Englishmen, died shortly after in 1329.

Bruce's death prompted the Second War of Scottish Independence, when Edward III of England invaded again to place a Balliol claimant on the Scottish throne. This led to more decades of war and English occupation until a peace treaty in 1357 after England's attention was captured by the developing Hundred Years' War in France.[39] After these wars, England and Scotland, which had previously been on track towards friendship, became hateful enemies.

The Stuarts in Scotland[edit]

Scottish culture and English wars[edit]

The House of Stewart (eventually changed to Stuart), which takes its name from the hereditary title "High Steward of Scotland", took the throne in 1371 after King David II died without issue. The first decades of the Stewart reign were mostly unimpressive, as Scotland was focused inward at the time. In 1468, Scotland received the Shetland and Orkney islands as a marriage dowry from Norway. So, uh, that was nice. Probably the biggest events were the founding of prestigious universities across Scotland such as the University of St Andrews![]() (1413), University of Glasgow

(1413), University of Glasgow![]() (1450), and the University of Aberdeen

(1450), and the University of Aberdeen![]() (1495), and the passage of the Education Act of 1496, which decreed that all sons of landholders should attend grammar schools.[40] Scotland was influenced by the Renaissance at this time, leading to a development in Scottish culture.[41]

(1495), and the passage of the Education Act of 1496, which decreed that all sons of landholders should attend grammar schools.[40] Scotland was influenced by the Renaissance at this time, leading to a development in Scottish culture.[41]

James IV, who took the throne in 1488, embarked on a major expansion of the Scottish Royal Navy before launching Scotland into a war with England.[42] English king Henry VII wasn't really in the mood for fighting, so he agreed to a "Treaty of Perpetual Peace" and had James IV marry his daughter, Margaret Tudor, in 1503.[42] As it turns out, "perpetual peace" means about 10 years, because James IV invaded England in 1513 to honor Scotland's Auld Alliance with France.[42] Although he led the largest Scottish army ever to enter England (~25,000 men), the invasion was a disaster that resulted in a massive defeat and the king's own death. Damn.

Scotland and the Reformation[edit]

During the early 1500s, the Protestant Reformation started to sweep over Europe. In 1533, England's king Henry VIII had his country join it by forcing through the Act in Restraint of Appeals to cut the papacy out of England's legal system. He followed up in 1534 with the Act of Royal Supremacy, which placed himself as the leader of the Church of England. This all gave Scotland a position of vital importance in European politics, as it had a land border with England that Catholic powers could use as an invasion path.[44] Scotland's king James V had also married a French noblewoman and fathered a daughter, Mary, in 1542. Mary became Europe's most desirable bachelorette, as she had blood claims to both the English throne (from James IV) and the French one.[44] Determined to create a dynastic union between England and Scotland, Henry VIII began a brutal and bloody war called the "rough wooing" in 1544 that resulted in the sacking of Edinburgh that same year.[45] Although Scotland burned and suffered during the war, Henry VIII failed to force the marriage and instead ended the war with nothing but piles of debt.

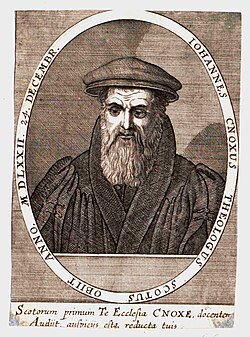

During this time, the influence of Protestantism gradually grew among Scotland's people. With Mary too young to rule and her mother (Queen Regent Marie de Guise) unpopular, royal authority was weak in Scotland, preventing any effective centralized effort at stomping out the movement.[44] Scottish Protestant preacher John Knox, who had studied with Calvinists in Switzerland, rallied opposition against Mary and her mother by publishing a pamphlet, "The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women," in 1558.[46] Scottish nobles who had been swayed to Protestantism (such as the Earls of Argyll, Glencairn and Morton) signed a "Covenant" in which they swore to convert the country.[47] They decided to call themselves the "Lords of the Congregation". Meanwhile, John Knox gave a sermon in May 1559 that was so inflammatory that it sparked a deadly riot across the city of Perth.[47] When Marie tried to intervene, the Lords of the Congregation rebelled with help from English queen Elizabeth I.[47] Marie, understandably, died of stress that year.

Without any kind of royal authorization, the Lords of the Congregation assembled a body called the Reformation Parliament in 1560, which outlawed Catholic worship in Scotland.[44] It also organized various Protestant thinkers such as John Knox to set doctrine for the Church of Scotland. The Church took on a decidedly Calvinist flavor, with church buildings stripped of religious art and whitewashed so attendees would focus on Jesus rather than images.

Elizabeth and Mary[edit]

Queen Elizabeth wasn't done meddling in Scottish affairs. Her cousin Mary returned to rule Scotland in 1561 after the death of her mother and regent; Mary had been living in France during her childhood.[48] Her existence was a major threat to Elizabeth's rule in England. Mary had a claim to the throne due to her English descent, and her determined adherence to Catholicism made her a more fit ruler in the eyes of England's still-large Catholic minority.[48] Mary had a similar problem, for although her reign was widely accepted, she was still a Catholic queen of a majority Protestant nation. She appealed to Elizabeth's sense of kinship, calling the two of them queens "in one isle, of one language, the nearest kinswomen that each other had".[48] But this call to unity fell on deaf ears when Mary refused to sign a treaty that would have ruled her out of the English succession, pissing off the childless Elizabeth. Elizabeth also didn't really consider family as being all that important, which is understandable since her dad had executed her mom.[49]

Mary decided to marry a Scottish noble in 1565 in order to solidify her rule, and she chose Henry Stuart, the Lord Darnley. This was a very bad match, as Darnley was perpetually jealous of other men around her and craved power.[50] The story took a crazy turn as Darnley had the queen's secretary murdered in front of her while she was pregnant, and then Darnley himself was strangled to death in 1567. The prime suspect in Darnley's murder was James Hepburn, the Earl of Bothwell, and Mary created a scandal by marrying him soon after Darnley's death.[50] While Darnley wasn't a great guy or even a good one, marrying the person who murdered him almost immediately after it happened was a bad look.

Scottish nobles had Mary imprisoned and forced her to abdicate in favor of her infant son James in 1568, while Bothwell fled to Denmark. Now a pariah, Mary fled to England in the hopes that her beloved cousin and fellow queen Elizabeth could find it in her heart to — nah, Elizabeth had her thrown in house arrest.[50] She remained effectively a prisoner for 19 years, and her presence disturbed Elizabeth as discontented Catholics in England were fairly open about wanting to place Mary on the throne.[50] Eventually, Elizabeth decided that Mary's presence was intolerable. In 1587, Mary knelt in the great hall of Fotheringhay Castle, thanked her executioner for making "an end of all my troubles," and then died by beheading.[48]

The Union of Crowns (and growing religious conflict)[edit]

King James VI of Scotland, the son of Queen Mary and Lord Darnley, had a shitty childhood, as he became a political pawn for various regents and was even briefly captured.[51] Probably as a result of this, James believed strongly that kings should wield absolute power and only be accountable to God. The young king was also fascinated by witchcraft and magic (claiming to have had a vision of his mother's execution), and was an enthusiastic overseer of witch-hunts.[52]

In 1603, Elizabeth died childless, and England's nobles offered him the throne as her only eligible Protestant relative.[51] Although Scotland's king had taken control of England, it felt the other way around. James ruled both countries from Westminster, and he only returned to Scotland once, in 1617.[51] The rest of the time, he interacted with Scotland's government only via correspondence. During his time as King of England, James commissioned the King James Version of the Bible, oversaw the first steps in establishing England's colonial empire in North America, and fought politically with England's Parliament over how much authority the monarch should have. James was used to dealing with a far weaker Parliament in Scotland, and his inability to get them to agree on tax policy led to Parliament's dissolution in 1611, deadlock in 1614, and dissolution again in 1621.[51] Scotland also tried and largely failed to found a colony, Nova Scotia, in what is now Canada.[53] Another of James I's longest-reaching policies was the 15 years-long Plantation of Ireland, in which he encouraged Scottish Protestants to settle in Ireland, hoping this would subjugate its Catholic people.[54] The subjugation bit failed, but the Plantation did permanently alter the demographics of Northern Ireland and create the Ulster Scots![]() ethnic group.

ethnic group.

King James died in 1625, but his successor Charles I had inherited his father's views on the divine right of monarchs.[55] His relationship with the English Parliament was even worse, as he repeatedly dismissed and recalled them in the hopes of annoying them into doing what he wanted.[55] He even signed a false promise, the 1628 Petition of Right, which would have expanded Parliament's authority.[56] He promptly and stupidly reneged on this agreement, pissing off the English Parliament and putting England, Scotland, and Ireland on the path to war.

In Scotland, the hapless King Charles I pissed his own people off as well. The Church of Scotland differed from its English counterpart on several points of Christian doctrine that, while few people would give a shit today, were vitally important at the time. In 1637, Charles I ignored petitions from his Scottish subjects and enforced a new Prayer Book intended to force Scottish Protestants in line with English practices.[57] In protest, clergy and nobles across Scotland endorsed the 1638 National Covenant, expressing support for Scotland's unique brand of Protestantism. By 1639, both the Crown and the Covenanters were stockpiling arms for a military confrontation.[58] The resultant First Bishops' War![]() featured mostly skirmishes and ended later in 1639 with little accomplished. This peace was promptly broken in 1640 when the new Scottish Parliament both endorsed the Covenant and became paranoid that the Crown was going to invade again. The Second Bishops' War

featured mostly skirmishes and ended later in 1639 with little accomplished. This peace was promptly broken in 1640 when the new Scottish Parliament both endorsed the Covenant and became paranoid that the Crown was going to invade again. The Second Bishops' War![]() saw Scotland outright invade England, and it ended with Scottish victory and a humiliating peace agreement for Charles I in 1641.[58]

saw Scotland outright invade England, and it ended with Scottish victory and a humiliating peace agreement for Charles I in 1641.[58]

Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms[edit]

Despite being frequently called the "English Civil War," the Wars of the Three Kingdoms were actually started and ended by Scots. Conflict between Parliament and the Crown escalated to a breaking point in 1642, when the Scottish king Charles I barged into Parliament and attempted to arrest 5 of its members.[59] When his attempt failed, the king fled London and raised his banner, beginning the civil war.

The Covenanters remained aloof to either cause until 1643, when the English Parliament agreed to work towards creating a pan-British church by incorporating Presbyterian doctrine into the Church of England.[58] The ensuing theological discussions went nowhere, but it was enough to convince the Covenenters to throw in with the Parliamentarians. Scottish muscle became an integral part of the Parliamentarian forces, and they actually fielded the largest army of any faction in the war.[60] Assistance from the Covenanters was crucial in Parliament's victory at the 1644 Battle of Marston Moor, the largest battle of the war.[61] Royalist forces fell apart between that battle and 1646, forcing Charles I to surrender to a Scottish army.[57] After some negotiation, the Scots agreed to hand over their king in exchange for some cash from England to pay their country's debts.[57]

Unfortunately, Parliament had Charles I's head lopped off in 1649. They'd just executed Scotland's king without so much as a heads-up (sorry) to Scotland, which naturally infuriated them.[57] Scotland declared Charles II, who was in exile from the British Isles, as its king and joined the Royalist side. More war and bloodshed continued, with Scotland losing ground against the Puritan commander Oliver Cromwell. Scotland was crushed in 1653, and it spent several years under Cromwell's religious absolutist rule until his death in 1658.[62] Political chaos ensued at that point, as Cromwell's son wasn't up to the task of running the three realms, and Scottish armies marched towards London to persuade Parliament to allow Charles II to take the crown.[62] Charles II was crowned in 1660 after promising to pardon most people who had been involved in the wars (save for those who killed his father) and rule in partnership with Parliament.[63]

The Stuarts start shit again[edit]

King Charles II went right back to squabbling with the English Parliament, most particularly over the king's efforts to grant religious toleration to Catholics.[64] With supremely bad timing, the king's brother James converted to Catholicism and announced this to the country in 1673. This, combined with a rumor that France was planning to invade in order to place their fellow Catholic on the throne, caused anti-Catholic hysteria to sweep England and Scotland.[64] The English Parliament tried multiple times to pass the Exclusion Act, which would have excluded James from succession. A furious Charles II dissolved Parliament three times over this issue and then refused to call it into session at all.[64]

Charles II failed to produce an heir, and his death in 1685 resulted in the much-dreaded ascension of James II to the throne. He confirmed these fears by pushing a scandalous attempt to enshrine freedom of religion in his kingdoms, and then by placing Catholics in high office.[65] When, in 1688, the king had a son, Protestants were horrified at facing the prospect of a Catholic dynasty. To prevent this fate, they invited Prince William of Orange from the Netherlands to take the Crown, as he was married to James II's Protestant daughter, Mary.[65] When William arrived, Parliament accepted him, and James II fled London.

While this was happening, Scottish nobles and clergymen met in Edinburgh to determine how Scotland would respond to the overthrow of its own Stuart dynasty. James II had a real opportunity to win some support here, but he instead fucked it all up. He wrote a threatening and self-entitled letter to the convention, which contrasted sharply with William's polite and conciliatory missive.[65] In 1689, William and Mary were declared co-monarchs of Scotland. Although most of Scotland had sided with William, James II still had some shooters left in Scotland. The Jacobite cause (its name derived from the Latin form of "James") would remain influential in northern Scotland for centuries, with the Jacobite rising of 1689![]() occurring almost immediately.

occurring almost immediately.

The Acts of Union[edit]

In 1698, a Scottish ship embarked for Panama on a scheme to establish a colony there. The project was backed by nobles and businessmen from across Scotland, who all hoped that a Panamanian colony would become a trade hub between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.[66] Unfortunately, things weren't going so well in Scotland at this time. It had experienced multiple bad harvests in a row, and the country had been torn apart by civil war against the Jacobites. All of this combined to create a situation in which multiple Scottish parishes reported losing two-thirds of their population, a staggering loss of life comparable to the Black Death.[66] Even worse, the Panama project, which had been a last-ditch effort to get some cash flow into Scotland, failed disastrously. 2,000 colonists died in the attempt and disastrous amounts of debt were accrued.

All of this ruined Scotland's finances. England's Parliament, which was untouched by the disaster, opened negotiations for a full political union with Scotland. To speed things along, Parliament offered a carrot and a stick. It threatened to sever internal trade with Scotland should they refuse to negotiate, and it offered to pay off the debts that Scottish MPs had accrued by paying for the Panama scheme.[67] By early 1707, the debate was complete, and Scotland's parliament passed the Act of Union, paving the way for a political union with England. After England passed its own Act of Union later that year, the two kingdoms united into the Kingdom of Great Britain.[67] The Scottish Parliament and English Parliament were both abolished, being replaced by the expanded Parliament of Great Britain which met in London's Westminster Palace.[67] For centuries afterward, Scotland ceased to be a country, although it was permitted certain privileges like being able to retain the Church of Scotland as its established religion.

Scotland in the United Kingdom[edit]

“”How do you keep the natives off the booze long enough to pass the test?

|

| —Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh |

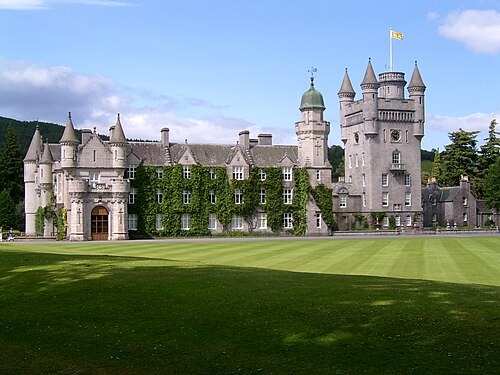

Within Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Scotland transformed into a leader in the Industrial Revolution.[70] The Scottish Enlightenment![]() also took hold during the 18th and 19th centuries, featuring such figures as the philosopher David Hume, who was known for his atheist-adjacent writings. As the unique Highlander culture declined, a Romantic revival saw tartans and kilts adopted by Scottish elites attempting to reconnect with their own culture.[71] Scotland's otherness led to both fascination and contempt from English elites. Scotland became a tourist destination, and Queen Victoria established Scotland's Balmoral Castle as a primary royal residence in 1852.[72]

also took hold during the 18th and 19th centuries, featuring such figures as the philosopher David Hume, who was known for his atheist-adjacent writings. As the unique Highlander culture declined, a Romantic revival saw tartans and kilts adopted by Scottish elites attempting to reconnect with their own culture.[71] Scotland's otherness led to both fascination and contempt from English elites. Scotland became a tourist destination, and Queen Victoria established Scotland's Balmoral Castle as a primary royal residence in 1852.[72]

Devolution[edit]

The concept of devolution started to pick up steam from the late 1970s to 1997 along with popular desire for government reform. Devolution would entail establishing a separate Scottish Parliament, reestablishing Scotland as a country. In 1978, Parliament's Labour majority passed a bill allowing Scotland to vote on devolution, but it failed despite majority approval (52%) because voter turnout (33%) was below the required level (40%).[73] It was clear that there was not a groundswell of support for Scotland having its own government.

Several things changed over time. First, between 1979 and 1997, the UK government was dominated by the Conservative Party despite Labour repeatedly winning a large majority of Scottish constituencies, such as in 1979![]() , 1983

, 1983![]() , and 1987

, and 1987![]() . Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was, justifiably, extremely unpopular in Scotland and widely seen as anti-Scottish.[74] (Also, see the "oil industry" section below). Additionally, in 1995 the movie Braveheart came out, which played a genuine role in reviving Scotland's interest in its own history of resistance against England despite numerous inaccuracies.[75] A renewal in Scottish nationalism was accompanied by commemorations of Scottish military victories like Bannockburn as well as constructions of memorial sites.[76]

. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was, justifiably, extremely unpopular in Scotland and widely seen as anti-Scottish.[74] (Also, see the "oil industry" section below). Additionally, in 1995 the movie Braveheart came out, which played a genuine role in reviving Scotland's interest in its own history of resistance against England despite numerous inaccuracies.[75] A renewal in Scottish nationalism was accompanied by commemorations of Scottish military victories like Bannockburn as well as constructions of memorial sites.[76]

After the ouster of the Tories in 1997, Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair delivered on his campaign promise of holding votes on devolution. On 11 September 1997, Scottish voters approved the creation of a Scottish Parliament by 74.3% and approved the idea that it should have powers over taxation by 63.5%.[73] The UK Parliament passed the Scotland Act 1998![]() in accordance with the devolution vote. The first elections for the Scottish Parliament were held on 6 May 1999, and Queen Elizabeth II opened the first session on 1 July.[77]

in accordance with the devolution vote. The first elections for the Scottish Parliament were held on 6 May 1999, and Queen Elizabeth II opened the first session on 1 July.[77]

Independence movement[edit]

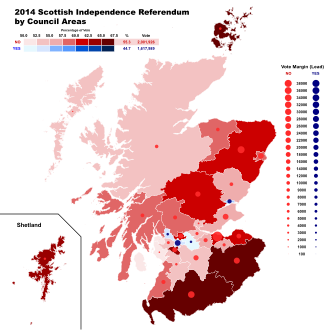

In May 2007, the pro-independence Scottish National Party won a historic victory in the Scottish parliamentary elections by securing a one-seat majority.[78] Chaos ensued with a re-count process, but it became clear that the SNP had indeed won and had the authority to put Scotland on a path to independence. After a bigger victory in 2011, the SNP government struck an agreement with Prime Minister David Cameron to allow an independence referendum to go forth in 2014 (not even Cameron's most fateful referendum agreement).[79] However, the SNP had overestimated the independence movement's popularity. While it had won two elections, the independence referendum it had championed went down in flames as Scottish voters rejected it 55.3% to 44.7%.[80] Voters were ultimately swayed by arguments against independence, such as the difficulty in separating from the UK and establishing its own institutions and the likely economic fallout from that process.[81]

While Scottish independence seemed like a dead cause at that point (as the Tories insisted), it received a major shot in the arm with the 2016 Brexit referendum result. Scotland voted overwhelmingly to remain in the European Union (62% to 38%), but the overall UK vote was narrowly in favor of leaving.[82] Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon denounced the result, stating that Scotland was being dragged out of the EU against its will and that a second independence referendum was "highly likely."[83] Matters were exacerbated when Boris Johnson became the UK's Prime Minister in 2019, as he was deeply unpopular in Scotland.[82] Pro-independence was consistently ahead in Scottish polls between 2020 and 2021.[82]

However, several major blows to the independence movement came right afterwards. First, the UK Supreme Court ruled in 2022 that Scotland could not hold another independence referendum without the UK Parliament's consent, which obviously would not be forthcoming.[84] Second, the SNP fucked up very badly. The party split itself over the issues of transgender rights and the Supreme Court ruling, leading to Sturgeon's decision to step down in 2023.[85] Authorities then arrested Sturgeon in January 2024 as part of a probe into her finances, which caused support for the "yes" vote to plummet along with her personal prestige.[86] Her husband was charged later that year for allegedly embezzling funds from the party.[87] And then, in the 2024 UK general election, SNP collapsed, losing 39 seats along with its once-formidable position as third-largest party in the UK Parliament.[88] For the moment, the independence movement once again appears dead.

Oil industry[edit]

Scotland is one of the world's major producers of crude oil thanks to drilling in the North Sea, and the industry began back in 1851.[89] As it became common knowledge that Scotland had the vast majority of the UK's oil reserves, the slogan "It's Scotland's Oil!" became extremely common in the 1970s and 80s, contributing to the rise of the Scottish National Party.[90] Scots resented the fact that their oil revenue was being used to pay for the unemployment receipts that followed the Conservative Party's deindustrialization program during the 1980s, and a caricature of Margaret Thatcher as an oil vampire became very popular.[91] They looked enviously at Norway, which used its share of the North Sea's oil to build a nationally-owned industry and create a sovereign wealth fund worth $1.3 trillion.[92] Scotland, meanwhile, had its oil industry privatized by the Thatcher government.

However, Scotland is now facing a major problem. between 2021 and 2023, its oil revenue dropped by half.[93] With oil production declining, a major debate emerged in Scotland about whether the UK government should issue new exploration licenses to companies so they can find new oil reserves.[94] Environmentalists argued against doing so, wanting Scotland to instead focus on developing green energy. As of 2024, the UK predicts that oil output will drop by another half by 2030 and then fall to a dismal 3% of 1999's peak production in 2050.[94]

Government and politics[edit]

Scotland is a constituent country of the United Kingdom, and as such is a constitutional monarchy ruled by King Charles III. It is governed largely by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which maintains that it is sovereign and therefore has the right to legislate on all matters relating to Scotland.[95] Devolution is therefore, according to the UK Parliament, an expression of that sovereignty that it has simply enacted out of the goodness of their hearts. How nice of them. As of 2024, 57 of 650 constituencies of the UK Parliament are in Scotland.[96]

The Scottish Parliament generally has authority to legislate on all issues not reserved by the UK Parliament. Reserved issues include foreign policy, national security, and social security.[97] Although the UK Parliament has the ability to legislate on devolved issues, it generally refrains from doing so by custom. It is a unicameral body with 129 members (MSPs): 73 are elected from constituencies, and 56 are elected by regional lists based on the additional-member system![]() .[98] Regional affiliates of the main UK parties are active in Scotland, such as the Scottish Conservatives

.[98] Regional affiliates of the main UK parties are active in Scotland, such as the Scottish Conservatives![]() , Scottish Labour

, Scottish Labour![]() , and the Scottish Liberal Democrats

, and the Scottish Liberal Democrats![]() . There is also, of course, the Scottish National Party. The Scottish Parliament building is located in Holyrood, a part of Edinburgh, and it's frequently referred to by that name.

. There is also, of course, the Scottish National Party. The Scottish Parliament building is located in Holyrood, a part of Edinburgh, and it's frequently referred to by that name.

Scotland's government is led by the First Minister, who appoints a cabinet and serves functions similarly to the UK Prime Minister.[99]

The monarchy[edit]

Scotland has a complicated relationship with the British monarchy. On one hand, many of the monarchy's symbols and artifacts are derived from Scotland. The Stone of Scone![]() , for example, is a legendary rock from a Scottish holy site that was used to crown Scotland's kings during the early Medieval period.[100] This tradition stopped in 1296, when King Edward Longshanks of England had it stolen, taken to Westminster, and built into an English coronation chair.[100] It has been used to crown English monarchs ever since, although it was given back to Scotland in 1996 to be housed in Edinburgh Castle.[101] It was temporarily taken back to Westminster in 2023 for the coronation of Charles III.[102] While it is just a fucking rock, it has become an important symbol for Scotland, and it was even briefly stolen from Westminster in 1950 by some Scottish students.[103]

, for example, is a legendary rock from a Scottish holy site that was used to crown Scotland's kings during the early Medieval period.[100] This tradition stopped in 1296, when King Edward Longshanks of England had it stolen, taken to Westminster, and built into an English coronation chair.[100] It has been used to crown English monarchs ever since, although it was given back to Scotland in 1996 to be housed in Edinburgh Castle.[101] It was temporarily taken back to Westminster in 2023 for the coronation of Charles III.[102] While it is just a fucking rock, it has become an important symbol for Scotland, and it was even briefly stolen from Westminster in 1950 by some Scottish students.[103]

The British royal family also holds the Honours of Scotland, the oldest set of Crown Jewels in the British Isles.[104] The Royal Arms of Scotland are incorporated into both the arms of the United Kingdom and the arms of the royal family. The title Duke of Rothesay![]() is also traditionally granted to the heir to the British throne.

is also traditionally granted to the heir to the British throne.

On the other hand, while the British monarchy has taken steps to incorporate Scottish elements into its traditions, it is still less popular in Scotland than in other countries of the UK. A 2023 YouGov poll found that only 46% of Scots approved of the monarchy, a higher number than the 40% support for a republic but still not great.[105] The same poll asked if Scots would support maintaining the monarchy in the event that it became independent, and it found that only 41% would support this. These numbers followed a nationwide UK trend with the ascension of the unpopular Charles III to the throne. A 2024 poll found that only 48% of people across the United Kingdom supported the monarchy, while fewer than half of UK citizens under age 55 would say they preferred the monarchy to a republic.[106]

Religion and secularism[edit]

Scotland is a majority non-religious country as of the 2022 census, with 51.1% of respondents stating this position.[3] It was a significant increase from 36.7% in 2011.[107] Rising secular attitudes has had a fairly significant impact on Scottish culture. In 2017, for instance, the Humanist Society of Scotland conducted more marriages than the Church of Scotland.[108] Humanist weddings are conducted without priests, registrars, or ministers. Other than that, they have all the same trappings as a religious wedding. They've been recognized by the Scottish government since 2005, and people travel from England and Wales, where they're not recognized, to have humanist wedding ceremonies.[108]

Additionally, the Church of Scotland, the country's national established church, is experiencing a sharp decline. In 2023, it announced that it would close hundreds of church buildings as it struggles with an aging clergy and financial woes.[109] Between 1982 and 2022, its membership declined by a shocking 70%, and the average age of its congregants is 62.[109] Only 60,000 people regularly attend services held by the Church of Scotland.[109] Perhaps in an attempt to slow the decline in its congregation, the Church of Scotland's General Assembly voted in 2022 to allow deacons and ministers to conduct same-sex marriages.[110]

The Catholic Church also suffered a drop in membership between 2011 and 2021, although it is the majority religion among people younger than 45 who identified with one.[111] This surprising number (the Catholics won the long game) is probably the result of a major influx of Catholic immigrants from Poland after World War II.[112] The numbers still don't look too good for them. In 1982, the Catholic Church conducted 4,870 marriages, while in 2021, they conducted only 812.[109]

Among other religions, 5.1% of respondents to the 2022 census identified as "other Christian," and 2.2% identified as Muslim.[107]

Languages[edit]

The top bit of Britain has always been a place with many languages, where influences from Scandinavia, England, Ireland, and further afield meet. The dominant language is (approximately) English, like wot Charlie speeks. Particularly in the north and west, Gaelic (descended from Old Irish) was widespread into the early modern era until rulers (in both Edinburgh and London) took steps to stamp it out. Once upon a time, Pictish was spoken in the east, Cambric (closely related to Welsh) in the south, and the northern isles spoke Norse as part of Norway. There are also quite a few Polish and South Asian people who still speak their parents' languages. The royal family spoke French for a while, and there were even Latin speakers once upon a time.[113] Certain nationalists want to deny this complex linguistic heritage and insist that everybody spoke Gaelic till the evil English made them stop.[114]

The other indigenous language is Scots, which is related to English but dates back to the early Anglian invasion of southeast Scotland in the 6th century CE. Scots was transported to Northern Ireland by Protestant settlers, where, as Ulster-Scots, it is now promoted by Unionists who are jealous of Nationalists and their strange language (Irish).[115] The precise nature and status of Scots is controversial, with some people insisting it's just a dialect of English or a vulgar way of speaking that isn't proper English; this is complicated by the fact that the term Scots doesn't refer to just one thing. Today, it is used for any language that isn't standard English that is spoken by indigenous residents of Scotland (including Doric - the Anglic dialect of Aberdeenshire - plus the recent urban speech of Glasgow and the Norse-inflected dialects of Orkney and Shetland), but around the 15th and 16th centuries it was the language of the Scottish court and Renaissance Scottish literature.[116]

Tartan myths[edit]

Scottish culture is full of symbols and objects that exemplify Scottish identity, but perhaps the greatest is Highland dress, the kilt, and the tartan from which it is made. Except most of this imagery is a 19th-century distortion: there is little medieval about the design of the modern kilt or its tartan. The image of Highland warriors clad in long tartan plaids taking on the English is popular, pre-dating Braveheart, but it is also largely false. Recent historians like Hugh Trevor-Roper have demonstrated that the modern tartan kilt was largely a Victorian invention or, at any rate, a Victorian popularisation of costumes of small historical and geographical range now taken to be universal in Scotland's history (Trevor-Roper was a staunch unionist, which may be relevant).[117]

Kilts and bare bottoms[edit]

The kilt commonly worn today, a pleated skirt-like garment that hangs from the waist to around the knee, and known as the modern kilt, small kilt, or walking kilt, was invented in the late 17th or early 18th century as a modification of the great kilt, a long tartan robe. Some reports say the modern kilt was invented in 1720 by Thomas Rawlinson, a Quaker from Lancashire, who halved the traditional kilt and sewed in pleats.[118] However, this idea is contested by others, and Rawlinson may merely have popularised an earlier design.[119] This was briefly popular, but tartan and the kilt were entirely banned in 1746 following the defeat of the Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden (part of the War of the Austrian Succession). It regained a niche when the ban was repealed in 1782. It only reached popularity as a Scottish national (as opposed to Highland) dress in 1822 when George IV became the first British monarch to visit Scotland since the 17th century.[118][119]

The traditional dress of the Scottish highlander was, in fact, not even the tartan great kilt seen in films such as Braveheart and Rob Roy. The full-length great kilt wrapped around the body was only developed in the 16th century (well after Wallace and the Bruce) from a smaller cloak worn over a tunic.[118] The fabric pattern was not typically the elaborate tartan known today: simple checks were common with those who could afford them, as were plain cloths. Before the evolution of the great kilt, Scots seem to have worn leggings with their cloaks rather than going bare-arsed.[120] In battle, medieval Scottish soldiers did not wear flowing kilts but chain mail or leather armour for obvious reasons such as not getting stabbed.[121] The Scots were not ignorant savages but in touch with European advances in arms, armour, military tactics, and fortifications, and many Scots fought in Europe as mercenaries.

Clan tartans[edit]

.jpg)

The Vestiarium Scoticum was a piece of fakelore published in Edinburgh in 1842 and claimed to be a 15th-century manuscript about the history of Scottish dress, reproduced from a 1721 edition; it was presented to the world by John Sobieski Stuart, who claimed to be a direct descendent of Prince Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) and the Polish royal family. Sobieski Stuart claimed that the book offered the history of the traditional tartans of various Scottish clans (tribal groups who controlled the Scottish Highlands). The book said each clan had a distinctive tartan design. Today, you can still go into a Scottish tartan shop, and somebody will sell you "your" specific tartan. But this notion of distinctive tartans identifying clans seems to have been a 19th-century idea.

The Vestiarium's accuracy was soon questioned, with an 1847 article in the Quarterly Review attacking both the Sobieski Stuart genealogy and the book's authenticity; they doubtless had another recent hoax of Scottish history in mind, the fake poems of the Celtic bard Ossian (see Fakelore). Various defences of the book followed, although no independent experts could view any of the old copies of the text. In 1895, the Glasgow Herald published a series of articles by Andrew Ross which investigated the Vestiarium more deeply: the 1721 edition had finally appeared from somewhere and was studied by various experts, who suggested the paper may have been treated by chemicals to artificially age it, adding to suspicions of fakery. Today the authors are identified as John and Charles Allen, two brothers with a fondness for tartan who were nonetheless not Scottish. Nonetheless, the book was by then essential to the Scottish tartan industry, and its fictional tartan designs are still widely used.[122][123][117]

There were likely regional traditions in fabric, and there is evidence of very ancient checked designs: the oldest known Scottish tartan is the Falkirk sett from the 3rd century CE.[120] But all the members of a clan did not wear the same tartan. Accounts of the 1746 battle of Culloden say that clans were distinguished by coloured ribbons on their hats.[124] David Morier's An Incident in the Rebellion of 1745, painted around 1760, shows soldiers with a variety of tartans, although there is no indication that different clans had specific designs.[125] But Morier's painting is inaccurate in portraying Jacobites armed with swords facing loyalists with guns. In reality, the Highland charge depended on running up to the enemy, firing muskets at close range and setting about with their swords.[126]

Today, some claim that tartan and the kilt were purely Victorian inventions; this is an overstatement.[120] But representations of the Wars of Scottish Independence with flowing kilts and bare arses are totally inaccurate.

Anti-Scottish sentiment[edit]

Scotland has been subjected to a long history of misconceptions and offensive stereotypes, primarily centred around inhabitants' accents or the country's alleged brutality. Much of this originates from the anti-Scottish sentiment established by medieval authors (who rarely visited the country but just went off "common knowledge"). In the 16th century, Scotland, particularly the Gaelic-speaking Highlands, was characterised as lawless, savage and filled with wild Scots.[127]

Another prominent belief is that the country still resembles Braveheart disregarding that film was set in the late 1400s and was, in fact, based on a poem by Blind Harry.[128]

In the modern day, anti-Scottish sentiment has continued to be present. An English football supporter was banned for life in 2015 for shouting "Kill all the Jocks" before attacking Scottish football fans.[129] One Scottish woman says she was forced to move from her home in England because of anti-Scottish feelings,[130] while another had a haggis thrown through her front window.[131] In 2008 a student nurse from London was fined for assault and hurling anti-Scottish abuse at police while drunk during the T in the Park festival in Kinross.[132] In another incident, a pregnant woman in South Shields attacked a random shopper because of her Scottish accent.[133]

Due to the nature of racial categories, it is hard to distinguish if anti-Scottish sentiment is, in fact, racist. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall argues that the idea of race is dependent on changing social and political relations. Whether or not one is racialised depends, at any given time, on one's relationship to power. As Scottish people have long been seen as British, they cannot be subject to Racism.

However, as the disparity of power grows between Scotland and the rest of the UK, such as remaining tensions over devolution, the West Lothian question![]() and the Barnett formula

and the Barnett formula![]() anti-Scottish sentiment seems to have grown.[135] Anti-Scottish sentiment can be further argued to be a form of bigotry.

anti-Scottish sentiment seems to have grown.[135] Anti-Scottish sentiment can be further argued to be a form of bigotry.

Gallery[edit]

Cullen skink

(Wikipedia link so you know this is a real name) served with bread.

(Wikipedia link so you know this is a real name) served with bread.

See also[edit]

- England

- No True Scotsman

- Northern Ireland

- The Canadian maritime province of Nova Scotia, which is Latin for "New Scotland"

- Scottish National Party

- West Lothian Question

- Essay:Too small, too poor, too stupid

- United Kingdom

- Wales

- Church of Scotland

- Siol nan Gaidheal

References[edit]

- ↑ Scottish quote of the week: Voltaire. The Scotsman.

- ↑ 10 Braveheart inaccuracies: historical blunders in the Mel Gibson film about the Wars of Scottish Independence. The Scotsman.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Most Scots have no religion - census. BBC News.

- ↑ Address Tae A Haggis

- ↑ Americans can only purchase "homegrown" or imitation haggis

- ↑ How Glasgow Cut Crime After Once Being The 'Murder Capital Of Europe'. NPR.

- ↑ How Scotland stemmed the tide of knife crime. BBC News.

- ↑ Ancient History of Scotland. Scotland.org

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Ancient Scotland. World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Roman Britain. World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 The Romans in Scotland. Historic UK.

- ↑ The Roman invasions of Scotland: You’re not in Rome now. Scotland Magazine.

- ↑ Forsyth, Katherine (2005). "Origins: Scotland to 1100". In Wormald, Jenny (ed.). Scotland: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199601646. p. 25–26 .

- ↑ Where Did the Gaelic Language Come From? Ireland or Scotland? Global Language Services.

- ↑ Saint Ninian. Britannica.

- ↑ The arrival of Christianity in Scotland. Historic Environment Scotland.

- ↑ St. Columba. Britannica.

- ↑ Iona Abbey. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Vikings in Scotland. Sons of Vikings.

- ↑ King Kenneth I. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ How 'Scotland's first king' unified a country during troubling times. The National.

- ↑ Strathclyde. Britannica.

- ↑ Scotland: The unification of the kingdom. Britannica.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Macbeth, King of Scotland. World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 King David I. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 King Malcolm IV. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 King William I. Undisclosed Scotland.

- ↑ The Death of Alexander II of Scots. History Today.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 King Alexander III. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Edward I 'Longshanks' (r. 1272-1307). Royal.uk

- ↑ The Auld Alliance. Historic UK.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 The True Story of Robert the Bruce, Scotland’s ‘Outlaw King’. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 William Wallace. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ Andrew Murray. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ How William Wallace of ‘Braveheart’ Fame Defeated the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ King Robert the Bruce: Part 2. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ Bannockburn. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ King Robert the Bruce: Part 3. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ Scottish Wars of Independence. Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ Bawcutt, Priscilla J.; Williams, Janet Hadley, eds. (2006). A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry. D.S. Brewer. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-843-84096-1. OL 17210473M.

- ↑ Dawson, Jane E. A. (2007). Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-74-861455-4. OL 20000490M. p. 117.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 King James IV. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ John Knox on Female Leadership. World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 The Scottish Reformation, c.1525-1560. Scottish History Society.

- ↑ Lessons from England’s 16th Century ‘Rough Wooing’ of Scotland. History Net.

- ↑ John Knox and the Scottish Reformation. Historic UK.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Marie of Guise: Life Story, Chapter 10 : Rebellion (1557 - 1560). Tudor Times.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 The True Story of Mary, Queen of Scots, and Elizabeth I. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ Who were Henry VIII's wives? Royal Museums Greenwich.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/elizabeth-i-mary-queen-scots Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots. Royal Museums Greenwhich.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 James I of England. World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Why was King James VI and I obsessed with witch hunts? History Extra.

- ↑ Mitchison, Rosalind (2002) [1982]. A History of Scotland (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41-527880-5. OL 3952705M. p 176.

- ↑ The linguistic history of Ulster By Prof. Michael Montgomery. BBC.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Charles I of England. World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Petition of Right. World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 Scots started and ended the English Civil War. Scottish Field.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 The National Covenant, 1637-60. The Scottish History Society.

- ↑ The Origins & Causes of the English Civil War. Historic UK.

- ↑ How Scots ‘Taleban’ and crack forces won Civil War. The Scotsman.

- ↑ Battle of Marston Moor. World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Oliver Cromwell. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ Haley, K.H.D. (1985). Politics in the Reign of Charles II. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-13928-1. p. 5.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 King Charles II. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 King James VII/II. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 The Darien Scheme: Scotland’s Unsuccessful Settlement in the Americas. The Collector.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 The Union of 1707: the Historical Context. Scottish History Society.

- ↑ Queen Elizabeth II has died. BBC News.

- ↑ Prince Philip: 90 of the Duke of Edinburgh's most excruciating gaffes and jokes by Heather Saul (Friday 17 July 2015) The Independent.

- ↑ The Industrial Revolution. BBC.

- ↑ Ferguson, William (1998). The Identity of the Scottish Nation: An Historic Quest. ISBN 978-0-748-61072-3. OL 74480M.p. 227

- ↑ M. Sievers, The Highland Myth as an Invented Tradition of 18th and 19th century and Its Significance for the Image of Scotland (GRIN Verlag, 2007), pp. 22–5.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 History of the Scottish Parliament: The path to devolution. Parliament of Scotland.

- ↑ Margaret Thatcher's legacy in Scotland, 25 years after her downfall. BBC News.

- ↑ Tories have revived their hatred and fear of favourite bogeyman Braveheart. The National.

- ↑ Hintz, Claire, "[https://digitalcommons.hollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1033&context=ughonors Robert the Bruce Fights for Scottish Independence Once Again: The Influence of Nationalism and Myth in Scotland's Modern Pursuit of Independence]" (2021).]

- ↑ The Scottish Parliament re-established. Parliament of Scotland.

- ↑ SNP wins historic victory. The Guardian.

- ↑ Scottish independence: Cameron and Salmond strike referendum deal. BBC News.

- ↑ Scotland votes NO. BBC News.

- ↑ Why Scottish independence is a bad idea. Vox.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 Scottish independence: How did we get here and what happens next? BBC News.

- ↑ Brexit: Nicola Sturgeon says second Scottish independence vote 'highly likely'. BBC News.

- ↑ Independence referendum: Scottish government loses indyref2 court case. BBC News.

- ↑ Scottish leader Sturgeon quits with independence goal unmet. Associated Press.

- ↑ Nicola Sturgeon’s ruined legacy . Politico.

- ↑ Peter Murrell charged with embezzlement in SNP finance probe. BBC News.

- ↑ Scotland's general election explained in numbers. BBC News.

- ↑ Glennie, KW (1998). Petroleum Geology of the North Sea: Basic Concepts and Recent Advances. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-632-03845-9.

- ↑ It's Scotland's Oil. University of Glasgow.

- ↑ The truth behind Scotland's oil and the McCrone Report. The National.

- ↑ What actually happened to Scotland's trillions in North Sea oil boom? The Herald.

- ↑ Scottish public spending deficit increases as oil revenues fall. BBC News.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Would new licences save the North Sea oil and gas industry? BBC News.

- ↑ Chapter 3: Parliamentary sovereignty. UK Parliament.

- ↑ Parliamentary constituencies. UK Parliament.

- ↑ The Scottish Government. Scotland.org

- ↑ How MSPs are elected. The Scottish Parliament.

- ↑ First Minister. The Scottish Parliament.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Stone of Scone. Undiscovered Scotland.

- ↑ The Stone of Destiny has a mysterious past beyond British coronations. National Geographic.

- ↑ Scotland's "Stone of Destiny has an ancient role in King Charles' coronation. Learn its centuries-old story. CBS News.

- ↑ Film on Stone of Destiny heist 'will end UK'. The Guardian.

- ↑ [https://www.royal.uk/honours-scotland The Honours of Scotland]. Royal.uk

- ↑ Another Look at Attitudes to the Monarchy. What Scotland Thinks.

- ↑ Support for the monarchy falls below 50 per cent for the first time. The National.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Scotland’s Census – religion, ethnic group, language and national identity results.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 What God has not joined together: the rise of the humanist wedding. The Guardian.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 109.3 ‘Anchors in our landscapes’: secular Scotland is fast losing its churches. The Guardian.

- ↑ Church of Scotland to allow same-sex marriages. BBC News.

- ↑ Scotland’s religious collapse. The Spectator.

- ↑ How Polish Catholics made a home in Scotland after WW2. Scottish Catholic Observer.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Languages of Scotland.

- ↑ Gaelic Civilisation: The Gaelic Soul of Alba, Sion nan Gaidheal website, accessed 11 Jan 2019

- ↑ Random thouchts on Ulster-Scotch, Slugger O'Toole, 27 Dec 2008

- ↑ Website help over Scots language, BBC, 28 Feb 2011

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 The Invention of Scotland by Hugh Trevor-Roper: review, Adam Sisman, The Daily Telegraph, June 6, 2008

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 See the Wikipedia article on History of the kilt.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 The History of Tartan, Country Life, August 8, 2014

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 A history of tartan: from Falkirk to Mod, Jude Stewart, The Scotsman, 2 Dec 2015

- ↑ Medieval arms and armour, Scottish Association of the Teachers of History website

- ↑ The Welsh brothers who sold Scotland's 'fake' tartan dream, The Scotsman, 31 Aug 2016

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Vestiarium Scoticum.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Tartan.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on David Morier.

- ↑ Culloden, battlefieldsofbritain.co.uk

- ↑ [ W. Camden, Britannia, or, A Chorographical description of the most flourishing kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. (London 1610), p114-127]

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "'Kill the Jocks' Thug is Caged; Curse of the Casuals Day 4 – Girlfriend Assaulted". Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ "Mum Run out of England for Being Scottish; Racist Hell: Victim Tells How Cats Were Killed and Home Burned". Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ "Police probe haggis 'hate crime'". BBC News. 23 May 2001. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Student nurse fined hundreds for assault and anti-Scottish abuse". STV News. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ↑ "Pregnant-woman-attacks-Scottish-shopper". Daily Mail. 2014-06-05. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ↑ Guardian rejects complaints from 300 readers who found Steve Bell ‘incest and Scottish country dancing’ cartoon racist. Press Gazette.

- ↑ Walker, Helen (3 December 2007). "Scottish MPs voice concern over increase in anti-Scottish sentiment". The Journal. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Categories: [Scotland] [United Kingdom] [European countries]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 11/08/2025 14:30:32 | 164 views

☰ Source: https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Scotland | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

_(9605427).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

,_1911.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

KSF

KSF