Schizophrenia

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki

| Schizophrenia | |

|---|---|

| |

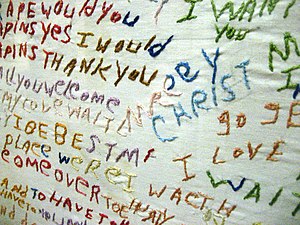

| Cloth embroidered by a person diagnosed with schizophrenia | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Hallucinations (usually hearing voices), delusions, confused thinking[2][3] |

| Complications | Suicide, heart disease, lifestyle diseases[4] |

| Usual onset | Ages 16 to 30[3] |

| Duration | Chronic[3] |

| Causes | Environmental and genetic factors[5] |

| Risk factors | Family history, cannabis use in adolescence, problems during pregnancy, childhood adversity, birth in late winter or early spring, older father, being born or raised in a city[5][6] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on observed behavior, reported experiences, and reports of others familiar with the person[7] |

| Differential diagnosis | Substance abuse, Huntington's disease, mood disorders (bipolar disorder), autism,[8] borderline personality disorder[9] |

| Management | Counseling, job training[2][5] |

| Medication | Antipsychotics[5] |

| Prognosis | 20 years shorter life expectancy[4][10] |

| Frequency | ~0.5%[11] |

| Deaths | ~17,000 (2015)[12] |

Schizophrenia is a mental illness characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis.[5] Major symptoms include hallucinations (often hearing voices), delusions (having beliefs not shared by others), and disorganized thinking.[7] Other symptoms include social withdrawal, decreased emotional expression, and lack of motivation.[5][13] Symptoms typically come on gradually, begin in young adulthood, and in many cases never resolve.[3][7] Many people with schizophrenia have other mental disorders such as an anxiety disorders including panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, or a substance use disorder.[7]

The causes include genetic and environmental factors.[5] Genetic factors include a variety of common and rare genetic variants.[14] Possible environmental factors include being raised in a city, cannabis use during adolescence, infections, the ages of a person's mother or father, and poor nutrition during pregnancy.[5][15] There is no objective diagnostic test; diagnosis is based on observed behavior, a history that includes the person's reported experiences, and reports of others familiar with the person.[7] To be diagnosed, symptoms and functional impairment need to be present for six months, (DSM-5), or one month, (ICD-11).[7][11]

About half of those diagnosed with schizophrenia will have a significant improvement over the long term with no further relapses, and a small proportion of these will recover completely.[7][16] The other half will have a lifelong impairment,[17] and severe cases may be repeatedly admitted to hospital.[16] Social problems such as long-term unemployment, poverty, homelessness, exploitation, and victimization are common consequences of schizophrenia.[18][19] Compared to the general population, people with schizophrenia have a higher suicide rate (about 5% overall) and more physical health problems,[20][21] leading to an average decreased life expectancy of 20 years.[10] In 2015, an estimated 17,000 deaths were caused by schizophrenia.[12]

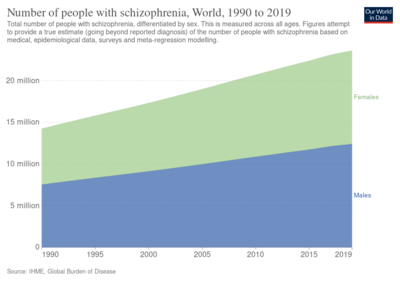

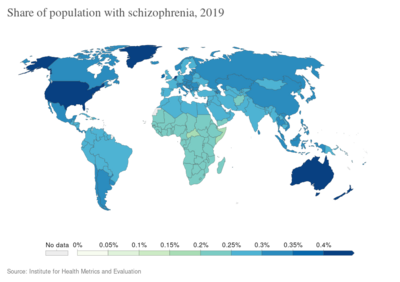

The mainstay of treatment is an antipsychotic medication, along with counselling, job training, and social rehabilitation.[5] Up to a third of people do not respond to initial antipsychotics, in which case the antipsychotic clozapine may be used.[22] In situations where there is a risk of harm to self or others, a short involuntary hospitalization may be necessary.[23] Long-term hospitalization may be needed for a small number of people with severe schizophrenia.[24] In countries where supportive services are limited or unavailable, long-term hospital stays are more typical.[25] About 0.3% to 0.7% of people are affected by schizophrenia during their lifetime.[26] In 2017, there were an estimated 1.1 million new cases and in 2019 a total of 20 million cases globally.[27][2] Males are more often affected and on average have an earlier onset.[2]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by significant alterations in perception, thoughts, mood, and behavior.[28] Symptoms are described in terms of positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms.[3][29] The positive symptoms of schizophrenia are the same for any psychosis and are sometimes referred to as psychotic symptoms. These may be present in any of the different psychoses, and are often transient making early diagnosis of schizophrenia problematic. Psychosis noted for the first time in a person who is later diagnosed with schizophrenia is referred to as a first-episode psychosis (FEP).[30][31]

Positive symptoms[edit | edit source]

Positive symptoms are those symptoms that are not normally experienced, but are present in people during a psychotic episode in schizophrenia. They include delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thoughts and speech, typically regarded as manifestations of psychosis.[30] Hallucinations most commonly involve the sense of hearing as hearing voices but can sometimes involve any of the other senses of taste, sight, smell, and touch.[32] They are also typically related to the content of the delusional theme.[33] Delusions are bizarre or persecutory in nature. Distortions of self-experience such as feeling as if one's thoughts or feelings are not really one's own, to believing that thoughts are being inserted into one's mind, sometimes termed passivity phenomena, are also common.[34] Thought disorders can include thought blocking, and disorganized speech – speech that is not understandable is known as word salad.[3][35] Positive symptoms generally respond well to medication,[5] and become reduced over the course of the illness, perhaps related to the age-related decline in dopamine activity.[7]

Negative symptoms[edit | edit source]

Negative symptoms are deficits of normal emotional responses or of other thought processes.[36] The five recognised domains of negative symptoms are: emotional blunting – showing flat expressions or little emotion; alogia – a poverty of speech; anhedonia – an inability to feel pleasure; asociality – the lack of desire to form relationships, and avolition – a lack of motivation and apathy.[37] Other related symptoms are social withdrawal,[38] self-neglect particularly in hygiene, and self-care, and loss of judgment.[36] Negative symptoms appear to contribute more to poor quality of life, functional impairment, and to the burden on others than do positive symptoms.[17][39] People with greater negative symptoms often have a history of poor adjustment before the onset of illness.[38] Negative symptoms are less responsive to medication, and are the most difficult to treat.[40][41]

Cognitive symptoms[edit | edit source]

Cognitive deficits are the earliest and most constantly found symptoms in schizophrenia. They are often evident long before the onset of illness in the prodromal stage, and may be present in early adolescence, or childhood.[42][43] They are a core feature but not considered to be core symptoms, as are positive and negative symptoms.[44][45] However, their presence and degree of dysfunction is taken as a better indicator of functionality than the presentation of core symptoms.[42] Cognitive deficits become worse at first episode psychosis but then return to baseline, and remain fairly stable over the course of the illness.[46][47]

The deficits in cognition are seen to drive the negative psychosocial outcome in schizophrenia, and are claimed to equate to a possible reduction in IQ from the norm of 100 to 70–85.[48][49] Cognitive deficits may be of neurocognition (nonsocial) or of social cognition.[50] Neurocognition is the ability to receive and remember information, and includes verbal fluency, memory, reasoning, problem solving, speed of processing, and auditory and visual perception.[47] Verbal memory and attention are seen to be the most affected.[51][49] Verbal memory impairment is associated with a decreased level of semantic processing (relating meaning to words).[52] Another memory impairment is that of episodic memory.[53] An impairment in visual perception that is consistently found in schizophrenia is that of visual backward masking.[47] Visual processing impairments include an inability to perceive complex visual illusions.[54] Social cognition is concerned with the mental operations needed to interpret, and understand the self and others in the social world.[50][47] This is also an associated impairment, and facial emotion perception is often found to be difficult.[55][56] Facial perception is critical for ordinary social interaction.[57] Cognitive impairments do not usually respond to antipsychotics, and there are a number of interventions that are used to try to improve them.

Onset[edit | edit source]

Onset typically occurs between the late teens and early 30s, with the peak incidence occurring in males in the early to mid twenties, and in females in the late twenties.[3][7][11] Onset before the age of 17 is known as early-onset,[58] and before the age of 13, as can sometimes occur is known as childhood schizophrenia or very early-onset.[59][7] A later stage of onset can occur between the ages of 40 and 60, known as late-onset schizophrenia.[50] A later onset over the age of 60 which may be difficult to differentiate as schizophrenia, is known as very-late-onset schizophrenia-like psychosis.[50] Late onset has shown that a higher rate of females are affected; they have less severe symptoms, and need lower doses of antipsychotics.[50] The earlier favouring of onset in males is later seen to be balanced by a post-menopausal increase in the development in females. Estrogen produced pre-menopause, has a dampening effect on dopamine receptors but its protection can be overridden by a genetic overload.[60] There has been a dramatic increase in the numbers of older adults with schizophrenia.[61] An estimated 70% of those with schizophrenia have cognitive deficits, and these are most pronounced in early onset, and late-onset illness.[50][62] There has been a dramatic increase in the numbers of older adults with schizophrenia.[61] An estimated 70% of those with schizophrenia have cognitive deficits, and these are most pronounced in early onset, and late-onset illness.[50][62]

Onset may happen suddenly, or may occur after the slow and gradual development of a number of signs and symptoms in a period known as the prodromal stage.[7] Up to 75% of those with schizophrenia go through a prodromal stage.[63] The negative and cognitive symptoms in the prodrome can precede FEP by many months, and up to five years.[64][46] The period from FEP and treatment is known as the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) which is seen to be a factor in functional outcome. The prodromal stage is the high-risk stage for the development of psychosis.[47] Since the progression to first episode psychosis, is not inevitable an alternative term is often preferred of at risk mental state[47] Recognition and early intervention at the prodromal stage would minimize the disruption to educational and social development associated with schizophrenia, and has been the focus of many studies.[64][46] It is suggested that the use of anti-inflammatory compounds such as D-serine may prevent the transition to schizophrenia.[46] Cognitive symptoms are not secondary to positive symptoms, or to the side effects of antipsychotics.[47]

Cognitive impairments in the prodromal stage become worse after first episode psychosis (after which they return to baseline and then remain fairly stable), making early intervention to prevent such transition of prime importance.[46] Early treatment with cognitive behavioral therapies are the gold standard.[64] Neurological soft signs of clumsiness and loss of fine motor movement are often found in schizophrenia, and these resolve with effective treatment of FEP.[65][11]

Causes[edit | edit source]

Genetic, environmental, and vulnerability factors are involved in the development of schizophrenia.[66][5] The interactions of these risk factors are complex, as numerous and diverse insults from conception to adulthood can be involved.[66] A genetic predisposition on its own, without interacting environmental factors, will not give rise to the development of schizophrenia.[67][66] Schizophrenia is described as a neurodevelopmental disorder that lacks a precise boundary in its definition.[68][67]

Genetic[edit | edit source]

Estimates of the heritability of schizophrenia are between 70% and 80%, which implies that 70% to 80% of the individual differences in risk to schizophrenia is associated with genetics.[69][14] These estimates vary because of the difficulty in separating genetic and environmental influences, and their accuracy has been queried.[70][71] The greatest risk factor for developing schizophrenia is having a first-degree relative with the disease (risk is 6.5%); more than 40% of identical twins of those with schizophrenia are also affected.[72] If one parent is affected the risk is about 13% and if both are affected the risk is nearly 50%.[69] However, DSM-5 points out that most people with schizophrenia have no family history of psychosis.[7] Results of candidate gene studies of schizophrenia have generally failed to find consistent associations,[73] and the genetic loci identified by genome-wide association studies as associated with schizophrenia explain only a small fraction of the variation in the disease.[74]

Many genes are known to be involved in schizophrenia, each with small effect and unknown transmission and expression.[14][75] The summation of these effect sizes into a polygenic risk score can explain at least 7% of the variability in liability for schizophrenia.[76] Around 5% of cases of schizophrenia are understood to be at least partially attributable to rare copy-number variations (CNVs); these structural variations are associated with known genomic disorders involving deletions at 22q11.2 (DiGeorge syndrome), duplications at 16p11.2 16p11.2 duplication (most frequently found) and deletions at 15q11.2 (Burnside-Butler syndrome).[77] Some of these CNVs increase the risk of developing schizophrenia by as much as 20-fold, and are frequently comorbid with autism and intellectual disabilities.[77]

The genes CRHR1 and CRHBP have been shown to be associated with a severity of suicidal behavior. These genes code for stress response proteins needed in the control of the HPA axis, and their interaction can affect this axis. Response to stress can cause lasting changes in the function of the HPA axis possibly disrupting the negative feedback mechanism, homeostasis, and the regulation of emotion leading to altered behaviors.[67]

The question of how schizophrenia could be primarily genetically influenced, given that people with schizophrenia have lower fertility rates, is a paradox. It is expected that genetic variants that increase the risk of schizophrenia would be selected against due to their negative effects on reproductive fitness. A number of potential explanations have been proposed, including that alleles associated with schizophrenia risk confers a fitness advantage in unaffected individuals.[78][79] While some evidence has not supported this idea,[71] others propose that a large number of alleles each contributing a small amount can persist.[80]

Environment[edit | edit source]

Environmental factors, each associated with a slight risk of developing schizophrenia in later life include oxygen deprivation, infection, prenatal maternal stress, and malnutrition in the mother during fetal development.[20] A risk is also associated with maternal obesity, in increasing oxidative stress, and dysregulating the dopamine and serotonin pathways.[81] Both maternal stress and infection have been demonstrated to alter fetal neurodevelopment through an increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[82] There is a slighter risk associated with being born in the winter or spring possibly due to vitamin D deficiency[83] or a prenatal viral infection.[72] Other infections during pregnancy or around the time of birth that have been linked to an increased risk include infections by Toxoplasma gondii and Chlamydia.[84] The increased risk is about five to eight percent.[85] Viral infections of the brain during childhood are also linked to a risk of schizophrenia during adulthood.[86]

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), severe forms of which are classed as childhood trauma, range from being bullied or abused, to the death of a parent.[87] Many adverse childhood experiences can cause toxic stress and increase the risk of psychosis.[88][89][87] Schizophrenia was the last diagnosis to benefit from the link made between ACEs and adult mental health outcomes.[90]

Living in an urban environment during childhood or as an adult has consistently been found to increase the risk of schizophrenia by a factor of two,[20][91] even after taking into account drug use, ethnic group, and size of social group.[92] A possible link between the urban environment and pollution has been suggested to be the cause of the elevated risk of schizophrenia.[93]

Other risk factors of importance include social isolation, immigration related to social adversity and racial discrimination, family dysfunction, unemployment, and poor housing conditions.[72][94] Having a father older than 40 years, or parents younger than 20 years are also associated with schizophrenia.[5][95]

Substance use[edit | edit source]

About half of those with schizophrenia use recreational drugs, including cannabis, nicotine, and alcohol excessively.[96][97] Use of stimulants such as amphetamine and cocaine can lead to a temporary stimulant psychosis, which presents very similarly to schizophrenia. Rarely, alcohol use can also result in a similar alcohol-related psychosis.[72][98] Drugs may also be used as coping mechanisms by people who have schizophrenia, to deal with depression, anxiety, boredom, and loneliness.[96][99] The use of cannabis and tobacco are not associated with the development of cognitive deficits, and sometimes a reverse relationship is found where their use improves these symptoms.[45] However, substance abuse is associated with an increased risk of suicide, and a poor response to treatment.[100]

Cannabis-use may be a contributory factor in the development of schizophrenia, potentially increasing the risk of the disease in those who are already at risk.[15] The increased risk may require the presence of certain genes within an individual.[15] Its use is associated with doubling the rate.[101] The use of more potent strains of cannabis having a high level of its active ingredient tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), increases the risk further. One of these strains is well known as skunk.[102][103]

Mechanisms[edit | edit source]

The mechanisms of schizophrenia are unknown, and a number of models have been put forward to explain the link between altered brain function and schizophrenia.[20] One of the most common is the dopamine model, which attributes psychosis to the mind's faulty interpretation of the misfiring of dopaminergic neurons.[104] This has been directly related to the symptoms of delusions and hallucinations.[20][105][106][107] Abnormal dopamine signaling has been implicated in schizophrenia based on the usefulness of medications that affect the dopamine receptor and the observation that dopamine levels are increased during acute psychosis.[108][109] A decrease in D1 receptors in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may also be responsible for deficits in working memory.[110][111]

Another hypothesis is the glutamate model that links alterations between glutamatergic neurotransmission and neural oscillations that affect connections between the thalamus and the cortex.[112] Studies have shown that a reduced expression of a glutamate receptor – NMDA receptor, and glutamate blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with schizophrenia.[113][114][112] Post-mortem studies consistently find that a subset of these neurons fail to express GAD67 (GAD1),[115] in addition to abnormalities in brain morphometry. The subsets of interneurons that are abnormal in schizophrenia are responsible for the synchronizing of neural ensembles needed during working memory tasks. These give the neural oscillations produced as gamma waves that have a frequency of between 30 and 80 hertz. Both working memory tasks and gamma waves are impaired in schizophrenia, which may reflect abnormal interneuron functionality.[115][116][117][118]

There are often impairments in cognition, social skills, and motor skills before the onset of schizophrenia, which suggests a neurodevelopmental model.[119] Such frameworks have hypothesized links between these biological abnormalities and symptoms.[120] Furthermore, problems before birth such as maternal infection, maternal malnutrition and complications during pregnancy all increase risk for schizophrenia.[5][121] Schizophrenia usually emerges 18-25, an age period that overlaps with certain stages of neurodevelopment that are implicated in schizophrenia.[122]

Deficits in executive functions, such as planning, inhibition, and working memory, are pervasive in schizophrenia. Although these functions are dissociable, their dysfunction in schizophrenia may reflect an underlying deficit in the ability to represent goal related information in working memory, and to utilize this to direct cognition and behavior.[123][124] These impairments have been linked to a number of neuroimaging and neuropathological abnormalities. For example, functional neuroimaging studies report evidence of reduced neural processing efficiency, whereby the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is activated to a greater degree to achieve a certain level of performance relative to controls on working memory tasks. These abnormalities may be linked to the consistent post-mortem finding of reduced neuropil, evidenced by increased pyramidal cell density and reduced dendritic spine density. These cellular and functional abnormalities may also be reflected in structural neuroimaging studies that find reduced grey matter volume in association with deficits in working memory tasks.[125]

Positive symptoms have been linked to reduced cortical thickness in the superior temporal gyrus.[126] Severity of negative symptoms has been linked to reduced thickness in the left medial orbitofrontal cortex.[127] Anhedonia, traditionally defined as a reduced capacity to experience pleasure, is frequently reported in schizophrenia. However, a large body of evidence suggests that hedonic responses are intact in schizophrenia,[128] and that what is reported to be anhedonia is a reflection of dysfunction in other processes related to reward.[129] Overall, a failure of reward prediction is thought to lead to impairment in the generation of cognition and behavior required to obtain rewards, despite normal hedonic responses.[130]

It has been hypothesized that in some people, development of schizophrenia is related to intestinal tract dysfunction such as seen with non-celiac gluten sensitivity or abnormalities in the gut microbiota.[131] A subgroup of persons with schizophrenia present an immune response to gluten differently from that found in people with celiac, with elevated levels of certain serum biomarkers of gluten sensitivity such as anti-gliadin IgG or anti-gliadin IgA antibodies.[132]

Another theory links abnormal brain lateralization to the development of being left-handed which is significantly more common in those with schizophrenia.[133] This abnormal development of hemispheric asymmetry is noted in schizophrenia.[134] Studies have concluded that the link is a true and verifiable effect that may reflect a genetic link between lateralization and schizophrenia.[133][135]

Bayesian models of brain functioning have been utilized to link abnormalities in cellular functioning to symptoms.[136][137] Both hallucinations and delusions have been suggested to reflect improper encoding of prior expectations, thereby causing expectation to excessively influence sensory perception and the formation of beliefs. In approved models of circuits that mediate predictive coding, reduced NMDA receptor activation, could in theory result in the positive symptoms of delusions and hallucinations.[138][139][140]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

There is no objective test or biomarker to confirm diagnosis. Psychoses can occur in several conditions and are often transient making early diagnosis of schizophrenia difficult. Psychosis noted for the first time in a person that is later diagnosed with schizophrenia is referred to as a first-episode psychosis (FEP).

Criteria[edit | edit source]

Schizophrenia is diagnosed based on criteria in either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) published by the American Psychiatric Association, or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) published by the World Health Organization. These criteria use the self-reported experiences of the person and reported abnormalities in behavior, followed by a psychiatric assessment. The mental status examination is an important part of the assessment.[141] An established tool for assessing the severity of positive and negative symptoms is the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).[142] This has been seen to have shortcomings relating to negative symptoms, and other scales – the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS), and the Brief Negative Symptoms Scale (BNSS) have been introduced.[41] DSM-5, the fifth edition was published in 2013, and gives a Scale to Assess the Severity of Symptom Dimensions outlining eight dimensions of symptoms.[44]

DSM-5 states that to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, two diagnostic criteria have to be met over the period of one month, with a significant impact on social or occupational functioning for at least six months. One of the symptoms needs to be either delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech. A second symptom could be one of the negative symptoms, or severely disorganized or catatonic behaviour.[7] A different diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder can be made before the six months needed for the diagnosis of schizophrenia.[7]

In Australia the guideline for diagnosis is for six months or more with symptoms severe enough to affect ordinary functioning.[143] In the UK diagnosis is based on having the symptoms for most of the time for one month, with symptoms that significantly affect the ability to work, study, or to carry on ordinary daily living, and with other similar conditions ruled out.[144]

The ICD criteria are typically used in European countries; the DSM criteria are used predominantly in the United States and Canada, and are prevailing in research studies. In practice, agreement between the two systems is high.[145] The current proposal for the ICD-11 criteria for schizophrenia recommends adding self-disorder as a symptom.[34]

A major unresolved difference between the two diagnostic systems is that of the requirement in DSM of an impaired functional outcome. WHO for ICD argues that not all people with schizophrenia have functional deficits and so these are not specific for the diagnosis.[44]

Changes made[edit | edit source]

Both manuals have adopted the chapter heading of Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders; ICD modifying this as Schizophrenia spectrum and other primary psychotic disorders.[44] The definition of schizophrenia remains essentially the same as that specified by the 2000 text revised DSM-IV (DSM-IV-TR). However, with the publication of DSM-5, the APA removed all sub-classifications of schizophrenia.[44] ICD-11 has also removed subtypes. The removed subtype from both, of catatonic has been relisted in ICD-11 as a psychomotor disturbance that may be present in schizophrenia.[44]

Another major change was to remove the importance previously given to Schneider's first-rank symptoms.[146] DSM-5 still uses the listing of schizophreniform disorder but ICD-11 no longer includes it.[44] DSM-5 also recommends that a better distinction be made between a current condition of schizophrenia and its historical progress, to achieve a clearer overall characterization.[146]

A dimensional assessment has been included in DSM-5 covering eight dimensions of symptoms to be rated (using the Scale to Assess the Severity of Symptom Dimensions) – these include the five diagnostic criteria plus cognitive impairments, mania, and depression.[44] This can add relevant information for the individual in regard to treatment, prognosis, and functional outcome; it also enables the response to treatment to be more accurately described.[44][147]

Two of the negative symptoms – avolition and diminished emotional expression, have been given more prominence in both manuals.[44]

Comorbidities[edit | edit source]

Many people with schizophrenia have one or more other disorders that often includes an anxiety disorder such as panic disorder, an obsessive-compulsive disorder, or a substance use disorder. These are separate disorders that need separate treatments.[7] Sleep disorders are commonly found with schizophrenia, and are early signs of illness and also of relapse.[148] Sleep disorders are linked with positive symptoms that include disorganized thinking and can adversely affect neocortical plasticity and cognition.[148] The consolidation of memories is disrupted in sleep disorders.[149] They are associated with severity of illness, a poor prognosis, and poor quality of life.[150][151] Sleep onset and maintenance insomnia is a common symptom, regardless of whether treatment has been received or not.[150] There is also a clozapine-induced somnolence. A related condition is antipsychotic-induced restless legs syndrome. Genetic variations have been found associated with these conditions involving the circadian rhythm, dopamine and histamine metabolism, and signal transduction.[152]

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Psychotic symptoms lasting less than a month may be diagnosed as brief psychotic disorder, and various conditions may be classed as psychotic disorder not otherwise specified; schizoaffective disorder is diagnosed if symptoms of mood disorder are substantially present alongside psychotic symptoms. If the psychotic symptoms are the direct physiological result of a general medical condition or a substance, then the diagnosis is one of a psychosis secondary to that condition. Schizophrenia is not diagnosed if symptoms of pervasive developmental disorder are present unless prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present.[7]

Psychotic symptoms may be present in several other conditions, and mental disorders, including bipolar disorder,[8] borderline personality disorder,[9] substance intoxication, substance-induced psychosis, and a number of drug withdrawal syndromes. Non-bizarre delusions are also present in delusional disorder, and social withdrawal in social anxiety disorder, avoidant personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder. Schizotypal personality disorder has symptoms that are similar but less severe than those of schizophrenia.[7] Schizophrenia occurs along with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) considerably more often than could be explained by chance, although it can be difficult to distinguish obsessions that occur in OCD from the delusions of schizophrenia.[153]

A more general medical and neurological examination may be needed to rule out medical illnesses which may rarely produce psychotic schizophrenia-like symptoms, such as metabolic disturbance, systemic infection, syphilis, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, epilepsy, limbic encephalitis, and brain lesions. Stroke, multiple sclerosis, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and dementias such as Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, frontotemporal dementia, and the Lewy body dementias may also be associated with schizophrenia-like psychotic symptoms.[154] It may be necessary to rule out a delirium, which can be distinguished by visual hallucinations, acute onset and fluctuating level of consciousness, and indicates an underlying medical illness. Investigations are not generally repeated for relapse unless there is a specific medical indication or possible adverse effects from antipsychotic medication. In children hallucinations must be separated from typical childhood fantasies.[7]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Prevention of schizophrenia is difficult as there are no reliable markers for the later development of the disorder.[155] There is tentative though inconclusive evidence for the effectiveness of early intervention to prevent schizophrenia in the prodrome phase.[156] There is some evidence that early intervention in those with first-episode psychosis may improve short-term outcomes, but there is little benefit from these measures after five years.[20] Cognitive behavioral therapy may reduce the risk of psychosis in those at high risk after a year[157] and is recommended in this group, by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).[28] Another preventive measure is to avoid drugs that have been associated with development of the disorder, including cannabis, cocaine, and amphetamines.[72]

Antipsychotics are prescribed following a first-episode psychosis, and following remission a preventive maintenance use is continued to avoid relapse. However, it is recognised that some people do recover following a single episode and that long-term use of antipsychotics will not be needed but there is no way of identifying this group.[158]

Management[edit | edit source]

The primary treatment of schizophrenia is the use of antipsychotic medications, often in combination with psychosocial interventions and social supports.[20][159] Community support services including drop-in centers, visits by members of a community mental health team, supported employment,[160] and support groups are common. The time between the onset of psychotic symptoms to being given treatment – the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is associated with a poorer outcome in both the short term and the long term.[161]

Voluntary or involuntary admittance to hospital may be needed to treat a severe episode, however, hospital stays are as short as possible. In the UK large mental hospitals termed asylums began to be closed down in the 1950s with the advent of antipsychotics, and with an awareness of the negative impact of long-term hospital stays on recovery.[18] This process was known as deinstitutionalization, and community and supportive services were developed in order to support this change. Many other countries followed suit with the US starting in the 60s.[162] There will still remain a few people who do not improve enough to be discharged.[18][24] In those countries that lack the necessary supportive and social services long-term hospital stays are more usual.[25]

Medication[edit | edit source]

The first-line treatment for schizophrenia is an antipsychotic. The first-generation antipsychotics, now called typical antipsychotics, are dopamine antagonists that block D2 receptors, and affect the neurotransmission of dopamine. Those brought out later, the second-generation antipsychotics known as atypical antipsychotics, can also have effect on another neurotransmitter serotonin. Antipsychotics can reduce the symptoms of anxiety within hours of their use but for other symptoms they may take several days or weeks to reach their full effect.[30][163] They have little effect on negative and cognitive symptoms, which may be helped by additional psychotherapies and medications.[164] There is no single antipsychotic suitable for first-line treatment for everyone, as responses and tolerances vary between people.[165] Stopping medication may be considered after a single psychotic episode where there has been a full recovery with no symptoms for twelve months. Repeated relapses worsen the long-term outlook and the risk of relapse following a second episode is high, and long-term treatment is usually recommended.[166][167]

Tobacco smoking increases the metabolism of some antipsychotics, by strongly activitating CYP1A2 the enzyme that breaks them down, and a significant difference is found in these levels between smokers and non-smokers.[168][169][170] It is recommended that the dosage for those smokers on clozapine be increased by 50%, and for those on olanzapine by 30%.[169] The result of stopping smoking can lead to an increased concentration of the antipsychotic that may result in toxicity, so that monitoring of effects would need to take place with a view to decreasing the dosage; many symptoms may be noticeably worsened, and extreme fatigue, and seizures are also possible with a risk of relapse. Likewise those who resume smoking may need their dosages adjusted accordingly.[171][168] The altering effects are due to compounds in tobacco smoke and not to nicotine; the use of nicotine replacement therapy therefore has the equivalent effect of stopping smoking and monitoring would still be needed.[168]

About 30 to 50 percent of people with schizophrenia fail to accept that they have an illness or comply with their recommended treatment.[172] For those who are unwilling or unable to take medication regularly, long-acting injections of antipsychotics may be used,[173] which reduce the risk of relapse to a greater degree than oral medications.[174] When used in combination with psychosocial interventions, they may improve long-term adherence to treatment.[175]

Research findings suggested that other neurotransmission systems including serotonin, glutamate, GABA, and acetycholine were implicated in the development of schizophrenia, and that a more inclusive medication was needed.[170] A new first-in-class antipsychotic that targets multiple neurotransmitter systems called lumateperone (ITI-007), was trialed and approved by the FDA in December 2019 for the treatment of schizophrenia in adults.[176][177][170] Lumateperone is a small molecule agent that shows improved safety, and tolerance. It interacts with dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate in a complex, uniquely selective manner, and is seen to improve negative symptoms, and social functioning. Lumateperone was also found to reduce potential metabolic dysfunction, have lower rates of movement disorders, and have lower cardiovascular side effects such as a fast heart rate.[170]

Side effects[edit | edit source]

Typical antipsychotics are associated with a higher rate of movement disorders including akathisia. Some atypicals are associated with considerable weight gain, diabetes and the risk of metabolic syndrome.[178] Risperidone (atypical) has a similar rate of extrapyramidal symptoms to haloperidol (typical).[178] A rare but potentially lethal condition of neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) has been associated with the use of antipsychotics. Through its early recognition, and timely intervention rates have declined. However, an awareness of the syndrome is advised to enable intervention.[179] Another less rare condition of tardive dyskinesia can occur due to long-term use of antipsychotics, developing after many months or years of use. It is more often reported with use of typical antipsychotics.[180]

Clozapine is associated with side effects that include weight gain, tiredness, and hypersalivation. More serious adverse effects include seizures, NMS, neutropenia, and agranulocytosis (lowered white blood cell count) and its use needs careful monitoring.[181][182] Studies have found that antipsychotic treatment following NMS and neutropenia may sometimes be successfully rechallenged (restarted) with clozapine.[183][184]

Clozapine is also associated with thromboembolism (including pulmonary embolism), myocarditis, and cardiomyopathy.[185][186] A systematic review of clozapine-associated pulmonary embolism indicates that this adverse effect can often be fatal, and that it has an early onset, and is dose-dependent. The findings advised the consideration of using a prevention therapy for venous thromboembolism after starting treatment with clozapine, and continuing this for six months.[186] Constipation is three times more likely to occur with the use of clozapine, and severe cases can lead to ileus and bowel ischemia resulting in many fatalities.[181]

However, the risk of serious adverse effects from clozapine is low, and there are the beneficial effects to be gained of a reduced risk of suicide, and aggression.[187][188] Typical antipsychotics and atypical risperidone can have a side effect of sexual dysfunction.[72] Clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine are associated with beneficial effects on sexual functioning helped by various psychotherapies.[189] Unwanted side effects cause people to stop treatment, resulting in relapses.[190]

Treatment resistant schizophrenia[edit | edit source]

About half of those with schizophrenia will respond favourably to antipsychotics, and have a good return of functioning.[191] However, positive symptoms persist in up to a third of people. Following two trials of different antipsychotics over six weeks, that also prove ineffective, they will be classed as having treatment resistant schizophrenia (TRS), and clozapine will be offered.[192][22] Clozapine is of benefit to around half of this group although it has the potentially serious side effect of agranulocytosis (lowered white blood cell count) in less than 4% of people.[20][72][193] Between 12 and 20 per cent will not respond to clozapine and this group is said to have ultra treatment resistant schizophrenia.[192][194] ECT may be offered to treat TRS as an add-on therapy, and is shown to sometimes be of benefit.[194] A review concluded that this use only has an effect on medium-term TRS and that there is not enough evidence to support its use other than for this group.[195]

TRS is often accompanied by a low quality of life, and greater social dysfunction.[196] TRS may be the result of inadequate rather than inefficient treatment; it also may be a false label due to medication not being taken regularly, or at all.[188] About 16 per cent of people who had initially been responsive to treatment later develop resistance. This could relate to the length of time on APs, with treatment becoming less responsive.[197] This finding also supports the involvement of dopamine in the development of schizophrenia.[188] Studies suggest that TRS may be a more heritable form.[198]

TRS may be evident from first episode psychosis, or from a relapse. It can vary in its intensity and response to other therapies.[196] This variation is seen to possibly indicate an underlying neurobiology such as dopamine supersensitivity (DSS), glutamate or serotonin dysfunction, inflammation and oxidative stress.[192] Studies have found that dopamine supersensitivity is found in up to 70% of those with TRS.[199] The variation has led to the suggestion that treatment responsive and treatment resistant schizophrenia be considered as two different subtypes.[192][198] It is further suggested that if the subtypes could be distinguished at an early stage significant implications could follow for treatment considerations, and for research.[194] Neuroimaging studies have found a significant decrease in the volume of grey matter in those with TRS with no such change seen in those who are treatment responsive.[194] In those with ultra treatment resistance the decrease in grey matter volume was larger.[192][194]

A link has been made between the gut microbiota and the development of TRS. The most prevalent cause put forward for TRS is that of mutation in the genes responsible for drug effectiveness. These include liver enzyme genes that control the availability of a drug to brain targets, and genes responsible for the structure and function of these targets. In the colon the bacteria encode a hundred times more genes than exist in the human genome. Only a fraction of ingested drugs reach the colon, having been already exposed to small intestinal bacteria, and absorbed in the portal circulation. This small fraction is then subject to the metabolic action of many communities of bacteria. Activation of the drug depends on the composition and enzymes of the bacteria and of the specifics of the drug, and therefore a great deal of individual variation can affect both the usefulness of the drug and its tolerability. It is suggested that parenteral administration of antipsychotics would bypass the gut and be more successful in overcoming TRS. The composition of gut microbiota is variable between individuals, but they are seen to remain stable. However, phyla can change in response to many factors including ageing, diet, substance-use, and medications – especially antibiotics, laxatives, and antipsychotics. In FEP, schizophrenia has been linked to significant changes in the gut microbiota that can predict response to treatment.[200]

Psychosocial[edit | edit source]

A number of psychosocial interventions that include several types of psychotherapy may be useful in the treatment of schizophrenia such as: family therapy,[201] group therapy, cognitive remediation therapy,[202] cognitive behavioral therapy, and metacognitive training.[203] Skills training, and help with substance use, and weight management– often needed as a side effect of an antipsychotic, are also offered.[204] In the US, interventions for first episode psychosis have been brought together in an overall approach known as coordinated speciality care (CSC) and also includes support for education.[30] In the UK care across all phases is a similar approach that covers many of the treament guidelines recommended.[28] The aim is to reduce the number of relapses and stays in hospital.[201]

Other support services for education, employment, and housing are usually offered. For people suffering from severe schizophrenia, and discharged from a stay in hospital, these services are often brought together in an integrated approach to offer support in the community away from the hospital setting. In addition to medicine management, housing, and finances, assistance is given for more routine matters such as help with shopping and using public transport. This approach is known as assertive community treatment (ACT) and has been shown to achieve positive results in symptoms, social functioning and quality of life.[205][206] Another more intense approach is known as intensive care management (ICM). ICM is a stage further than ACT and emphasises support of high intensity in smaller caseloads, (less than twenty). This approach is to provide long-term care in the community. Studies show that ICM improves many of the relevant outcomes including social functioning.[207]

Some studies have shown little evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in either reducing symptoms or preventing relapse.[208][209] However, other studies have found that CBT does improve overall psychotic symptoms (when in use with medication) and has been recommended in Canada, but it has been seen here to have no effect on social function, relapse, or quality of life.[210] In the UK it is recommended as an add-on therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia, but is not supported for use in treatment resistant schizophrenia.[209][211] Arts therapies are seen to improve negative symptoms in some people, and are recommended by NICE in the UK.[163][212] This approach however, is criticised as having not been well-researched, and arts therapies are not recommended in Australian guidelines for example.[212][213][214] Peer support, in which people with personal experience of schizophrenia, provide help to each other, is of unclear benefit.[215]

Other[edit | edit source]

Exercise therapy has been shown to improve positive and negative symptoms, cognition, and improve quality of life.[216] Aerobic exercise has been shown to improve cognitive deficits of working memory and attention.[217] Exercise has also been shown to increase the volume of the hippocampus in those with schizophrenia. A decrease in hippocampal volume is one of the factors linked to the development of the disease.[216] However, there still remains the problem of increasing motivation for, and maintaining participation in physical activity.[218] Supervised sessions are recommended.[217] In the UK healthy eating advice is offered alongside exercise programs.[219]

An inadequate diet is often found in schizophrenia, and associated vitamin deficiencies including those of folate, and vitamin D are linked to the risk factors for the development of schizophrenia and for early death including heart disease.[220] Those with schizophrenia possibly have the worst diet of all the mental disorders. Lower levels of folate and vitamin D have been noted as significantly lower in first episode psychosis.[220] The use of supplemental folate is recommended.[221] A zinc deficiency has also been noted.[222] Vitamin B12 is also often deficient and this is linked to worse symptoms. Supplementation with B vitamins has been shown to significantly improve symptoms, and to put in reverse some of the cognitive deficits.[220] It is also suggested that the noted dysfunction in gut microbiota might benefit from the use of probiotics.[222]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Schizophrenia has great human and economic costs.[5] It results in a decreased life expectancy of 20 years.[10][4] This is primarily because of its association with obesity, poor diet, a sedentary lifestyle, and smoking, with an increased rate of suicide playing a lesser role.[10][223] Side effects of antipsychotics may also increase the risk.[10] These differences in life expectancy increased between the 1970s and 1990s.[224] An Australian study puts the rate of early death at 25 years, and views the main cause to be related to heart disease.[185] Primary polydipsia, or excessive fluid intake, is relatively common in people with chronic schizophrenia.[225][226] This may lead to hyponatremia which can be life-threatening. Antipsychotics can lead to a dry mouth, but there are several other factors that may contribute to the disorder. It is suggested to lead to a reduction in life expectancy by 13 per cent.[226] A study has suggested that real barriers to improving the mortality rate in schizophrenia are poverty, overlooking the symptoms of other illnesses, stress, stigma, and medication side effects, and that these need to be changed.[227]

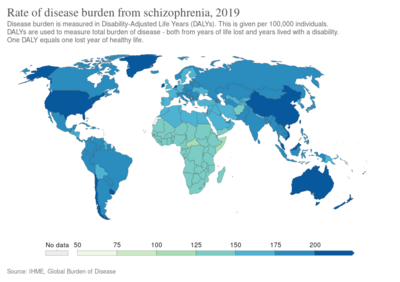

Schizophrenia is a major cause of disability. In 2016 it was classed as the 12th most disabling condition.[228] Approximately 75% of people with schizophrenia have ongoing disability with relapses[40] and 16.7 million people globally are deemed to have moderate or severe disability from the condition.[229] Some people do recover completely and others function well in society.[230] Most people with schizophrenia live independently with community support.[20] About 85% are unemployed.[5] In people with a first episode of psychosis in scizophrenia a good long-term outcome occurs in 31%, an intermediate outcome in 42% and a poor outcome in 31%.[231] Males are affected more often than females, and have a worse outcome.[232] Outcomes for schizophrenia appear better in the developing than the developed world.[233] These conclusions have been questioned.[234] Social problems, such as long-term unemployment, poverty, homelessness, exploitation, stigmatization and victimization are common consequences, and lead to social exclusion.[18][19]

There is a higher than average suicide rate associated with schizophrenia estimated at around 5% to 6%, most often occurring in the period following onset or first hospital admission.[21][11] Several times more (20 to 40%) attempt suicide at least once.[7][235] There are a variety of risk factors, including male gender, depression, a high IQ,[235] heavy smoking,[236] and substance abuse.[100] Repeated relapse is linked to an increased risk of suicidal behavior.[158] The use of clozapine can reduce the risk of suicide and aggression.[188]

Schizophrenia and smoking have shown a strong association in studies worldwide.[237][238] Use of cigarettes is especially high in those diagnosed with schizophrenia, with estimates ranging from 80 to 90% being regular smokers, as compared to 20% of the general population.[238] Those who smoke tend to smoke heavily, and additionally smoke cigarettes with high nicotine content.[33] Some propose that this is in an effort to improve symptoms.[239] Among people with schizophrenia use of cannabis is also common.[100]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

In 2017, the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated there were 1.1 million new cases, and in 2019 WHO reported a total of 20 million cases globally.[27][2] Schizophrenia affects around 0.3–0.7% of people at some point in their life.[26] It occurs 1.4 times more frequently in males than females and typically appears earlier in men[72] – the peak ages of onset are 25 years for males and 27 years for females.[240] Onset in childhood, before the age of 13 can sometimes occur.[7][59] A later onset can occur between the ages of 40 and 60, known as late onset, and also after 60 known as very late onset.[50]

Worldwide, schizophrenia is the most common psychotic disorder.[62] The frequency of schizophrenia varies across the world,[7][241] within countries,[242] and at the local and neighborhood level.[243] This variation has been estimated to be fivefold.[5] It causes approximately one percent of worldwide disability adjusted life years[72] and resulted in 17,000 deaths in 2015.[12]

In 2000, the World Health Organization found the percentage of people affected and the number of new cases that develop each year is roughly similar around the world, with age-standardized prevalence per 100,000 ranging from 343 in Africa to 544 in Japan and Oceania for men, and from 378 in Africa to 527 in Southeastern Europe for women.[244] About 1.1% of adults have schizophrenia in the United States.[245] However, in areas of conflict this figure can rise to between 4.0 and 6.5%.[246]

History[edit | edit source]

The history of schizophrenia is complex and does not lend itself easily to a linear narrative.[247] Accounts of a schizophrenia-like syndrome are rare in records before the 19th century. The earliest cases detailed were reported in 1797, and 1809.[248] Dementia praecox, meaning premature dementia was used by German psychiatrist Heinrich Schüle in 1886, and then in 1891 by Arnold Pick in a case report of hebephrenia. In 1893 Emil Kraepelin used the term in making a distinction, known as the Kraepelinian dichotomy, between the two psychoses – dementia praecox, and manic depression (now called bipolar disorder).[10] Kraepelin believed that dementia praecox was probably caused by a systemic disease that affected many organs and nerves, affecting the brain after puberty in a final decisive cascade.[249] It was thought to be an early form of dementia, a degenerative disease.[10] When it became evident that the disorder was not degenerative it was renamed schizophrenia by Eugen Bleuler in 1908.[250]

The word schizophrenia translates roughly as "splitting of the mind" and is Modern Latin from the Greek roots schizein (σχίζειν, "to split") and phrēn, (φρεν, "mind")[251] Its use was intended to describe the separation of function between personality, thinking, memory, and perception.[250]

The term schizophrenia used to be associated with split personality by the general population but that usage went into decline when split personality became known as a separate disorder, first as multiple identity disorder , and later as dissociative identity disorder.[252] In 2002 in Japan the name was changed to integration disorder, and in 2012 in South Korea, the name was changed to attunement disorder to reduce the stigma, both with good results.[20][253][254]

In the early 20th century, the psychiatrist Kurt Schneider listed the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia into two groups of hallucinations, and delusions. The hallucinations were listed as specific to auditory, and the delusional included thought disorders. These were seen as the symptoms of first-rank importance and were termed first-rank symptoms. Whilst these were also sometimes seen to be relevant to the psychosis in manic-depression, they were highly suggestive of schizophrenia and typically referred to as first-rank symptoms of schizophrenia. The most common first-rank symptom was found to belong to thought disorders.[255][256] In 2013 the first-rank symptoms were excluded from the DSM-5 criteria.[146] First-rank symptoms are seen to be of limited use in detecting schizophrenia but may be of help in differential diagnosis.[257]

The earliest attempts to treat schizophrenia were psychosurgical, involving either the removal of brain tissue from different regions or the severing of pathways.[258] These were notably frontal lobotomies and cingulotomies which were carried out from the 1930s.[258][259] In the 1930s a number of shock therapies were introduced which induced seizures (convulsions) or comas.[260] Insulin shock therapy involved the injecting of large doses of insulin in order to induce comas, which in turn produced hypoglycemia and convulsions.[260][259] The use of electricity to induce seizures was developed, and in use as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) by 1938.[261] Stereotactic surgeries were developed in the 1940s.[261] Treatment was revolutionized in the mid-1950s with the development and introduction of the first typical antipsychotic, chlorpromazine.[262] In the 1970s the first atypical antipsychotic clozapine, was introduced followed by the introduction of others.[263]

In the early 1970s in the US, the diagnostic model used for schizophrenia was broad and clinically-based using DSM II. It had been noted that schizophrenia was diagnosed far more in the US than in Europe which had been using the ICD-9 criteria. The US model was criticised for failing to demarcate clearly those people with a mental illness, and those without. In 1980 DSM III was published and showed a shift in focus from the clinically-based biopsychosocial model to a reason-based medical model.[264] DSM IV showed an increased focus to an evidence-based medical model.[265] DSM-5 was published in 2013 and introduced changes to DSM IV.

Society and culture[edit | edit source]

In 2002, the term for schizophrenia in Japan was changed from seishin-bunretsu-byō (精神分裂病, lit. "mind-split disease") to tōgō-shitchō-shō (統合失調症, lit. "integration-dysregulation syndrome") to reduce stigma.[266] The new name also interpreted as "integration disorder" was inspired by the biopsychosocial model; it increased the percentage of people who were informed of the diagnosis from 37 to 70% over three years.[253] A similar change was made in South Korea in 2012 to attunement disorder.[254] A professor of psychiatry, Jim van Os, has proposed changing the English term to psychosis spectrum syndrome.[267] In 2013 with the reviewed DSM-5, the DSM-5 committee was in favor of giving a new name to schizophrenia but they referred this to WHO.[268]

In the United States, the cost of schizophrenia – including direct costs (outpatient, inpatient, drugs, and long-term care) and non-health care costs (law enforcement, reduced workplace productivity, and unemployment) – was estimated to be $62.7 billion in 2002.[269] In the UK the cost in 2016 was put at £11.8 billion per year with a third of that figure directly attributable to the cost of hospital and social care, and treatment.[5]

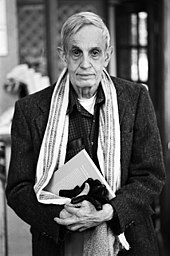

The book A Beautiful Mind chronicled the life of John Forbes Nash who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia but who went on to win the Nobel Prize for Economics. This was later made into the film with the same name. An earlier documentary was made with the title A Brilliant Madness.

In 1964 a lengthy case study of three males diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia who each had the delusional belief that they were Jesus Christ was published as a book. This has the title of The Three Christs of Ypsilanti, and a film with the title Three Christs was released in 2020. Such religious delusions are a fairly common feature in psychoses including schizophrenia.[270][271]

Violence[edit | edit source]

People with severe mental illness, including schizophrenia, are at a significantly greater risk of being victims of both violent and non-violent crime.[272] Schizophrenia has been associated with a higher rate of violent acts, but most appear to be related to associated substance abuse.[273] Rates of homicide linked to psychosis are similar to those linked to substance misuse, and parallel the overall rate in a region.[274] What role schizophrenia has on violence independent of drug misuse is controversial, but certain aspects of individual histories or mental states may be factors.[275] About 11% of people in prison for homicide have schizophrenia and 21% have mood disorders.[needs update][276] Another study found about 8-10% of people with schizophrenia had committed a violent act in the past year compared to 2% of the general population.[needs update][276]

Media coverage relating to violent acts by people with schizophrenia reinforces public perception of an association between schizophrenia and violence.[273] In a large, representative sample from a 1999 study, 12.8% of Americans believed that those with schizophrenia were "very likely" to do something violent against others, and 48.1% said that they were "somewhat likely" to. Over 74% said that people with schizophrenia were either "not very able" or "not able at all" to make decisions concerning their treatment, and 70.2% said the same of money-management decisions.[needs update][277] The perception of people with psychosis as violent more than doubled between the 1950s and 2000, according to one meta-analysis.[278]

Research directions[edit | edit source]

Schizophrenia is not believed to occur in other animals[279] but it may be possible to develop a pharmacologically induced non-human primate model of schizophrenia.[280]

Effects of early intervention is an active area of research.[156] One important aspect of this research is early detection of at-risk individuals. This includes development of risk calculators[281] and methods for large-scale population screening.[282]

Various agents have been explored for possible effectiveness in treating negative symptoms, for which antipsychotics have been of little benefit.[283] There have been trials on medications with anti-inflammatory activity, based on the premise that inflammation might play a role in the pathology of schizophrenia.[284]

Research has found a tentative benefit in using minocycline, a broad-spectrum antibiotic, as an add-on treatment for schizophrenia. Reviews have found that minocycline as an add-on therapy appears to be effective in improving all dimensions of symptoms, and has been found to be safe and well tolerated, but larger studies are called for.[285][286]

A review of the effects of nidotherapy – efforts to change the environment to improve functional ability was inconclusive, and it was suggested that it be treated as an experimental approach.[287]

Various brain stimulation techniques are being studied to treat the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, in particular auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs).[288][289] A 2015 Cochrane review found unclear evidence of benefit.[290] Most studies focus on transcranial direct-current stimulation (tDCM), and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).[289] Techniques based on focused ultrasound for deep brain stimulation could provide insight for the treatment of AVHs.[289]

Another active area of research is the study of a variety of potential biomarkers that would be of invaluable help not only in the diagnosis but also in the treatment and prognosis of schizophrenia. Possible biomarkers include markers of inflammation, neuroimaging, BDNF, genetics, and speech analysis. Some inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein are useful in detecting levels of inflammation implicated in some psychiatric disorders but they are not disorder-specific. However, other inflammatory cytokines are found to be elevated in first episode psychosis and acute relapse that are normalized after treatment with antipsychotics, and these may be considered as state markers.[291] Deficits in sleep spindles in schizophrenia may serve as a marker of an impaired thalamocortical circuit, and a mechanism for memory impairment.[149]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Jones D (2003) [1917]. Roach P, Hartmann J, Setter J (eds.). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Schizophrenia Fact sheet". www.who.int. 4 October 2019. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Schizophrenia". National Institute of Mental Health. January 2016. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Medicinal treatment of psychosis/schizophrenia". www.sbu.se. Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB (July 2016). "Schizophrenia". Lancet. 388 (10039): 86–97. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6. PMC 4940219. PMID 26777917.

- ↑ Gruebner O, Rapp MA, Adli M, et al. (February 2017). "Cities and mental health". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 114 (8): 121–127. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121. PMC 5374256. PMID 28302261.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 99–105. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ferri FF (2010). Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. p. Chapter S. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Paris J (December 2018). "Differential Diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 41 (4): 575–582. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2018.07.001. PMID 30447725.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB (2014). "Excess early mortality in schizophrenia". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 10: 425–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153657. PMID 24313570.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Ferri, Fred F. (2019). Ferri's clinical advisor 2019 : 5 books in 1. pp. 1225–1226. ISBN 9780323530422.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ "Types of psychosis". www.mind.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 van de Leemput J, Hess JL, Glatt SJ, Tsuang MT (2016). "Genetics of Schizophrenia: Historical Insights and Prevailing Evidence". Advances in Genetics. 96: 99–141. doi:10.1016/bs.adgen.2016.08.001. PMID 27968732.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Parakh P, Basu D (August 2013). "Cannabis and psychosis: have we found the missing links?". Asian Journal of Psychiatry (Review). 6 (4): 281–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.03.012. PMID 23810133.

Cannabis acts as a component cause of psychosis, that is, it increases the risk of psychosis in people with certain genetic or environmental vulnerabilities, though by itself, it is neither a sufficient nor a necessary cause of psychosis.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Vita A, Barlati S (May 2018). "Recovery from schizophrenia: is it possible?". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 31 (3): 246–255. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000407. PMID 29474266. S2CID 35299996.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lawrence, Ryan E.; First, Michael B.; Lieberman, Jeffrey A. (2015). "Chapter 48: Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses". In Tasman, Allan; Kay, Jerald; Lieberman, Jeffrey A.; First, Michael B.; Riba, Michelle B. (eds.). Psychiatry (fourth ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 798, 816, 819. doi:10.1002/9781118753378.ch48. ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Killaspy H (September 2014). "Contemporary mental health rehabilitation". East Asian Archives of Psychiatry. 24 (3): 89–94. PMID 25316799.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, et al. (17 October 2018). "Global Epidemiology and Burden of Schizophrenia: Findings From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 44 (6): 1195–1203. doi:10.1093/schbul/sby058. PMC 6192504. PMID 29762765.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 20.8 20.9 van Os J, Kapur S (August 2009). "Schizophrenia" (PDF). Lancet. 374 (9690): 635–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. PMID 19700006. S2CID 208792724. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Hor K, Taylor M (November 2010). "Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 24 (4 Suppl): 81–90. doi:10.1177/1359786810385490. PMC 2951591. PMID 20923923.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Siskind D, Siskind V, Kisely S (November 2017). "Clozapine Response Rates among People with Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: Data from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 62 (11): 772–777. doi:10.1177/0706743717718167. PMC 5697625. PMID 28655284.

- ↑ Becker T, Kilian R (2006). "Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: what can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care?". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 113 (429): 9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00711.x. PMID 16445476.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Capdevielle D, Boulenger JP, Villebrun D, Ritchie K (September 2009). "[Schizophrenic patients' length of stay: mental health care implication and medicoeconomic consequences]". Encephale (in French). 35 (4): 394–9. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2008.11.005. PMID 19748377.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ 25.0 25.1 Narayan KK, Kumar DS (January 2012). "Disability in a Group of Long-stay Patients with Schizophrenia: Experience from a Mental Hospital". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 34 (1): 70–5. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.96164. PMC 3361848. PMID 22661812.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Javitt DC (June 2014). "Balancing therapeutic safety and efficacy to improve clinical and economic outcomes in schizophrenia: a clinical overview". The American Journal of Managed Care. 20 (8 Suppl): S160-5. PMID 25180705.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 James SL, Abate D (November 2018). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". The Lancet. 392 (10159): 1789–1858. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. PMC 6227754. PMID 30496104.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management" (PDF). NICE. Mar 2014. pp. 4–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ↑ Stępnicki P, Kondej M, Kaczor AA (20 August 2018). "Current Concepts and Treatments of Schizophrenia". Molecules. 23 (8): 2087. doi:10.3390/molecules23082087. PMC 6222385. PMID 30127324.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 "NIMH » RAISE Questions and Answers". www.nimh.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ↑ Marshall M (September 2005). "Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: a systematic review". Archives of General Psychiatry. 62 (9): 975–83. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975. PMID 16143729.

- ↑ Császár N, Kapócs G, Bókkon I (27 May 2019). "A possible key role of vision in the development of schizophrenia". Reviews in the Neurosciences. 30 (4): 359–379. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2018-0022. PMID 30244235. S2CID 52813070.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 299–304. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Heinz A, Voss M, Lawrie SM, et al. (September 2016). "Shall we really say goodbye to first rank symptoms?". European Psychiatry. 37: 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.04.010. PMID 27429167.

- ↑ "National Institute of Mental Health". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Carson, Verna Benner (2000). Mental Health Nursing: The Nurse-patient Journey. W.B. Saunders. p. 638. ISBN 978-0-7216-8053-8. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016.

- ↑ Adida M, Azorin JM, Belzeaux R, Fakra E (December 2015). "[Negative symptoms: clinical and psychometric aspects]". Encephale (in French). 41 (6 Suppl 1): 6S15–7. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(16)30004-5. PMID 26776385.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ 38.0 38.1 Hirsch SR, Weinberger DR (2003). Schizophrenia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-632-06388-8. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ↑ Velligan DI, Alphs LD (1 March 2008). "Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: The Importance of Identification and Treatment". Psychiatric Times. 25 (3). Archived from the original on 6 October 2009.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Smith T, Weston C, Lieberman J (August 2010). "Schizophrenia (maintenance treatment)". American Family Physician. 82 (4): 338–9. PMID 20704164.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Marder SR, Kirkpatrick B (May 2014). "Defining and measuring negative symptoms of schizophrenia in clinical trials". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 24 (5): 737–43. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.10.016. PMID 24275698. S2CID 5172022.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Bozikas VP, Andreou C (February 2011). "Longitudinal studies of cognition in first episode psychosis: a systematic review of the literature". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 45 (2): 93–108. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.541418. PMID 21320033. S2CID 26135485.

- ↑ Shah JN, Qureshi SU, Jawaid A, Schulz PE (June 2012). "Is there evidence for late cognitive decline in chronic schizophrenia?". The Psychiatric Quarterly. 83 (2): 127–44. doi:10.1007/s11126-011-9189-8. PMID 21863346. S2CID 10970088.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 44.6 44.7 44.8 44.9 Biedermann F, Fleischhacker WW (August 2016). "Psychotic disorders in DSM-5 and ICD-11". CNS Spectrums. 21 (4): 349–54. doi:10.1017/S1092852916000316. PMID 27418328.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Vidailhet P (September 2013). "[First-episode psychosis, cognitive difficulties and remediation]". L'Encephale. 39 Suppl 2: S83-92. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(13)70101-5. PMID 24084427.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 Hashimoto K (5 July 2019). "Recent Advances in the Early Intervention in Schizophrenia: Future Direction from Preclinical Findings". Current Psychiatry Reports. 21 (8): 75. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1063-7. PMID 31278495. S2CID 195814019.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 47.6 Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J (June 2019). "Nonsocial and social cognition in schizophrenia: current evidence and future directions". World Psychiatry. 18 (2): 146–161. doi:10.1002/wps.20624. PMC 6502429. PMID 31059632.

- ↑ Javitt DC, Sweet RA (September 2015). "Auditory dysfunction in schizophrenia: integrating clinical and basic features". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 16 (9): 535–50. doi:10.1038/nrn4002. PMC 4692466. PMID 26289573.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Megreya AM (2016). "Face perception in schizophrenia: a specific deficit". Cognitive Neuropsychiatry. 21 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1080/13546805.2015.1133407. PMID 26816133. S2CID 26125559.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 50.6 50.7 Murante T, Cohen CI (January 2017). "Cognitive Functioning in Older Adults With Schizophrenia". Focus (American Psychiatric Publishing). 15 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1176/appi.focus.20160032. PMC 6519630. PMID 31975837.

- ↑ Eack SM (July 2012). "Cognitive remediation: a new generation of psychosocial interventions for people with schizophrenia". Social Work. 57 (3): 235–46. doi:10.1093/sw/sws008. PMC 3683242. PMID 23252315.

- ↑ Pomarol-Clotet E, Oh M, Laws KR, McKenna PJ (February 2008). "Semantic priming in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 192 (2): 92–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032102. hdl:2299/2735. PMID 18245021.

- ↑ Goldberg TE, Keefe RS, Goldman RS, Robinson DG, Harvey PD (April 2010). "Circumstances under which practice does not make perfect: a review of the practice effect literature in schizophrenia and its relevance to clinical treatment studies". Neuropsychopharmacology. 35 (5): 1053–62. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.211. PMC 3055399. PMID 20090669.

- ↑ King DJ, Hodgekins J, Chouinard PA, Chouinard VA, Sperandio I (June 2017). "A review of abnormalities in the perception of visual illusions in schizophrenia". Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 24 (3): 734–751. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1168-5. PMC 5486866. PMID 27730532.

- ↑ Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ (September 2010). "Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (5): 1009–19. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn192. PMC 2930336. PMID 19329561. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015.

- ↑ Le Gall, E; Iakimova, G (December 2018). "[Social cognition in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder: Points of convergence and functional differences]". L'Encephale. 44 (6): 523–537. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2018.03.004. PMID 30122298.

- ↑ Grill-Spector K, Weiner KS, Kay K, Gomez J (15 September 2017). "The Functional Neuroanatomy of Human Face Perception". Annual Review of Vision Science. 3: 167–196. doi:10.1146/annurev-vision-102016-061214. PMC 6345578. PMID 28715955.

- ↑ Bourgou Gaha S, Halayem Dhouib S, Amado I, Bouden A (June 2015). "[Neurological soft signs in early onset schizophrenia]". L'Encephale. 41 (3): 209–14. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2014.01.005. PMID 24854724.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Da Fonseca D, Fourneret P (December 2018). "[Very early onset schizophrenia]". L'Encephale. 44 (6S): S8–S11. doi:10.1016/S0013-7006(19)30071-5. PMID 30935493.