Balder

From Nwe

From Nwe

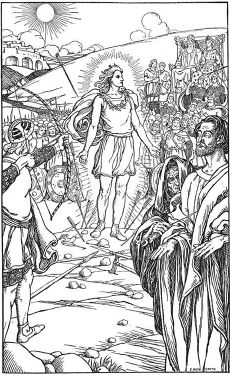

In Norse mythology, Balder (Old Norse: Baldr; Modern Icelandic and Faroese: Baldur; Modern Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, and anglicized Old Norse: Balder) is the god of innocence, beauty, joy, purity, and peace. He is also the second son of Odin, the head of the Norse pantheon.

Balder represents the spirit of hope and renewal in the world, and his death (at the hands of Loki) is one of the major precursors to the apocalypse (Ragnarök). Though few accounts of mythic events from the young god's life remain extant, the surviving tales of his death and eventual resurrection contain intriguing parallels to Christianity, Vedic Hinduism and Middle Eastern fertility cults.

Balder in a Norse Context

As a Norse deity, Balder belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E.[1] The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might.

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war. In fact, the most major divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[2] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Balder, the second son of Odin and a member of the Aesir, is the god of spring, innocence and joy.

Characteristics

Balder was best known as the Norse god of spring and renewal - an Adonis-like youth whose goodness, purity and overall pleasant disposition made him nearly impossible to dislike. The Prose Edda, written by Snorri Sturluson (1178-1241 C.E.), gives a clear indication of this characterization:

|

|

However, much like Persephone in the Greek tradition, Balder's primary import in the Norse tradition results from the mythic circumstances surrounding his untimely death (and his prophesied return after the fires of Ragnarök have burned out).

Mythic Representations

The Death and Return of Balder

The murder of Balder plays an important role in Nordic cosmology as a precursor to the eschaton (Ragnarök). The accounts of his murder often begin by describing a plague of sleep which fell upon the Aesir, when Frigg and Balder were tormented by dreams that the young god was going to die.[4] Since dreams were often understood to be prophetic, this motivated the boy's father (Odin) to set out to the depths of the underworld, to consult with the sprit of a deceased sibyl. Concerned by the prophetess's dire warnings, Balder's mother Frigg made every object on earth vow never to hurt Balder. All but one, a weed called the mistletoe, made this vow, as Frigg had thought it too unimportant and non-threatening to include. When Loki, the mischief-maker, heard of this, he made a magical spear (in some later versions, an arrow) from the mistletoe. He hurried to the place where the gods were indulging in their new pastime of hurling objects at Balder, which would bounce off without harming him. Loki gave the spear to Balder's brother, the blind god Höðr, who then inadvertently killed his brother with it. For this act, Odin and Rind had a child named Váli, who was born solely to punish Höðr, who was eventually hunted down and slain for his part in the tragedy.[5]

Balder was ceremonially burnt upon his ship, the Hringhorni, reputed to be largest of all ships. In the confusion surrounding the funeral, the dwarf Litr was kicked into the funeral pyre by Thor and burnt alive. Nanna, Balder's wife, also threw herself on the funeral pyre to await the end of Ragnarok when she would be reunited with her husband (though in alternate traditions, she simply died of grief). Balder's horse with all its trappings was also burned on the pyre. The ship was set to sea by Hyrrokin, a giantess, who came riding on a wolf and gave the ship such a push that fire flashed from the rollers and all the earth shook.

Upon Frigg's entreaties, delivered through the messenger Hermod, Hel promised to release Balder from the underworld if all objects alive and dead would weep for him. And all did, except a giantess, Thokk, who refused to mourn the slain god. Thus Balder had to remain in the underworld, not to emerge until after Ragnarok, when he and his brother Höðr would be reconciled and rule the new earth together with Thor's sons.[6]

Finally, when the gods discovered that the giantess had been Loki in disguise, they hunted him down, bound him to three rocks, and insured his continued torment until his fated release at Ragnarök. For more information on Loki's punishment, see the article on Loki.

Balder's Return

The eschatological themes introduced above were also especially prominent in the Völuspá, an unattributed poetic work from no later than the thirteenth century C.E., which goes into significant detail concerning the new heaven and a new earth that will emerge following the world-negating battle between the Aesir and Jotun. In this time, the seeress (who is the narrator of the text) describes how this promised land, where the fields unsown shall yield their increase and all sorrows shall be healed, will be ruled by the newly reborn Balder. In this realm, he will return to dwell in mansions of bliss, in a hall brighter than the sun, shingled with gold, where the righteous shall live in joy for ever more:

- 61. In wondrous beauty | once again

- Shall the golden tables | stand mid the grass,

- Which the gods had owned | in the days of old,

- 62. Then fields unsowed | bear ripened fruit,

- All ills grow better, | and Baldr comes back;

- Baldr and Hoth dwell | in Hropt's battle-hall,

- And the mighty gods: | would you know yet more?

- ...

- 64. More fair than the sun, | a hall I see,

- Roofed with gold, | on Gimle it stands;

- There shall the righteous | rulers dwell,

- And happiness ever | there shall they have.

- 65. There comes on high, | all power to hold,

- A mighty lord, | all lands he rules.[7]

Gesta Danorum

A variant (which casts the characters into semi-historical roles) can be found in the late 12th century version of the tale told by the old Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus (c.1150 - c.1220 C.E.). According to him, Balder and Høther were rival suitors for the hand of Nanna, daughter of Gewar, King of Norway. In this version, Balder was a demigod and common steel could not wound his sacred body. The two rivals encountered each other in a terrible battle, which eventually led to Balder being beaten and forced into exile.

- However, Balder, half-frenzied by his dreams of Nanna, in turn drove him into exile (winning the lady); finally Hother, befriended hy luck and the Wood Maidens, to whom he owed his early successes and his magic coat, belt, and girdle (there is obvious confusion here in the text), at last met Balder and stabbed him in the side. Of this wound Balder died in three days, as was foretold by the awful dream in which Proserpina (Hela) appeared to him. Balder's grand burial, his barrow, and the magic flood which burst from it when one Harald tried to break into it, and terrified the robbers, are described.[8]

In this account, the divine character of the tale (and much of its mythic resonance) is stripped away in favor of an attempt at historical accuracy (or an attempt to discredit "pagan" practices).

Inter-Religious Parallels

The mythology surrounding Balder, with its strong themes of resentment, loss and renewal, has resonances within many religio-cultural contexts. For example, the death of the "immortal" Balder resembles the demise of the invulnerable Zoroastrian hero Esfandyar in the epic Shahnameh.[9] In a similar manner, Lemminkäinen (a god in Finnish mythology), shares the same fate as Balder, as both are killed by "harmless" plants wielded by blind gods.[10] Turville-Petre also notes a considerable body of scholarship connecting the myths of Baldur's death and return to the Middle-Eastern fertility cults centering on the figures of Tammuz, Attis, Adonis, and Baal.[11]

Conversely, Georges Dumézil argues that the roles of Loki, Balder and Hod are paralleled by Duryodhana, Vidura/Yudhisthira and Dhrtarashtra in the Indian epic, Mahabarata.

- The method [used by Loki to kill Balder] is parallel to that which results in the provisional elimination and long exile of Yudhisthira: the demonic Duryodhana wrings authorization from the blind Dhrtarashtra to stage the scenario that will destroy Yudhisthira. This scenario is a game that is apparently without any particular danger for Yudhisthira, who is an average player, but it is one in which his adversary, accomplice of Duryodhana, uses supernatural tricks that force him, beaten, into exile.[12]

In an additionally intriguing parallel, Balder and Yudhisthira return to their respective homelands after the conclusion of the cataclysmic battle, and are able to usher in an era of peace and prosperity.[13]

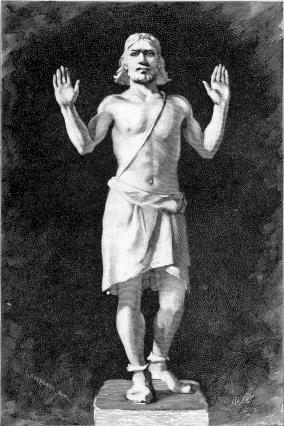

Balder has also been likened to Jesus Christ, likely due to the number of shared motifs between the two figures (a dying-and-rising god killed, though blameless, who heralds the arrival of a period of eternal peace). Such parallels (and even identifications) were especially striking in the versions of both tales that emerged from the Nordic world during the conversion of the region to Christianity - including a folk account of Christ being crucified on a mistletoe![14] However, "we need not go so far as [to] ... describe the cult of Balder as Christianity in pagan clothing, but it may well be allowed that Balder's character in the original Norse myth laid him open to Christian influences. Like Christ, Balder died, and like Christ he will return at the end of the world."[15]

Toponyms (and Other Linguistic Traces) of Balder

There are few place names in Scandinavia that contain the name of Balder. The most notable is the (former) parish named Baldishol in Hedmark county, Norway (where the last element is hóll meaning "mound; small hill"). Others (using his Norse name) may include Baldrsberg in Vestfold county, Baldrsheimr in Hordaland county Baldrsnes in Sør-Trøndelag county and the fjord and municipality Balsfjord in Troms county.

Also the Scandinavian language, terms the Scentless Mayweed (Matricaria perforata) "Balder's brows" because of its whiteness.

Notes

- ↑ John Lindow. Handbook of Norse mythology. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001), 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors… . As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen, Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning (XXII), (Brodeur, 36).

- ↑ This aspect of the tale is well told in the Eddic poem Baldrs Draumar ("The Dreams of Balder"), described and summarized in Gabriel Turville-Petrie. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964), 109-111.

- ↑ See Snorri Sturluson's Gylfaggining (XLIX-L), (Brodeur, 70-77) for a single, primary-source account of these events. See also P. A. Munch. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. (New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926), 80-94, for an accessible retelling; and Turville-Petre, 106-125, and Lindow, 65-69, for a more involved, scholarly perspective (addressing various versions of the tale).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Völuspá (61,62, 64, 65). Translated by Henry Adams Bellows (25-26) and accessed online at sacred-texts.com. See also Lindow, 317-319 for a concise summary of this text.

- ↑ Saxo Grammaticus, The Danish History (Introduction II: Gods and Goddesses), translated by Oliver Elton (New York: Norroena Society, 1905). Accessed online at The Online Medieval & Classical Library.

- ↑ See Professor Ehsan Yarshater's essay "ESFANDÎÂR" on the Circle of Ancient Iranian Studies website.

- ↑ Turville-Petre, 118.

- ↑ Ibid., 117-118.

- ↑ Dumézil, 63.

- ↑ Ibid., 64.

- ↑ Turville-Petre, 119.

- ↑ Ibid.

Bibliography

- Björnsson, Eysteinn (ed.). Snorra-Edda: Formáli & Gylfaginning: Textar fjögurra meginhandrita. 2005.

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0812217144

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0520020448.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1576072177

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0304363855

- Sturlson, Snorri. The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology. Introduced by Sigurdur Nordal; Selected and translated by Jean I. Young. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1954. ISBN 0520012313

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964.

- "Völuspá" in The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com. Retrieved June 26, 2019.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:39:50 | 55 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Balder | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF