Ancient Greece

From Nwe

From Nwe Ancient Greece is the period in Greek history that lasted for around one thousand years and ended with the rise of Christianity. It is considered by most historians to be the foundational culture of Western civilization. Greek culture was a powerful influence in the Roman Empire, which carried a version of it to many parts of Europe.

The civilization of the ancient Greeks has been immensely influential on the language, politics, educational systems, philosophy, science, and arts, fuelling the Renaissance in western Europe and again resurgent during various neoclassical revivals in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe and the Americas. Greek thought continues to inform discussion of ethics, politics, philosophy, and theology. The notion of democracy and some of the basic institutions of democratic governance are derived from the Athenian model. The word politics is derived from polis, the Greek city-state.

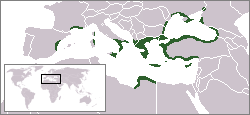

"Ancient Greece" is the term used to describe the Greek-speaking world in ancient times. It refers not only to the geographical peninsula of modern Greece, but also to areas of Hellenic culture that were settled in ancient times by Greeks: Cyprus and the Aegean islands, the Aegean coast of Anatolia (then known as Ionia), Sicily and southern Italy (known as Magna Graecia), and the scattered Greek settlements on the coasts of Colchis, Illyria, Thrace, Egypt, Cyrenaica, southern Gaul, east and northeast of the Iberian peninsula, Iberia and Taurica. Largely due to the way in which the Roman Empire borrowed and built on classical Greek culture and learning, Greek culture became part of the heritage of Europe and became intertwined with Christianity. It continues to be the foundation of much human thought across many spheres. Greek influence stands behind so many aspects of contemporary life that it is difficult to imagine what life would have been like had the ancient artistic, political, and intellectual life of Greece not flourished as it did.

At the same time that some of the great Greek thinkers were flourishing, Buddha and Confucius and others were also enlightening humanity elsewhere in the world. Axial Age theory posits that something very special was taking place at this time, laying the ethical and moral foundations that humanity needed in order to become what humanity is intended to be, that is, moral agents in a world over which they have responsibility for its welfare.

Chronology

There are no fixed or universally agreed upon dates for the beginning or the end of the ancient Greek period. In common usage it refers to all Greek history before the Roman Empire, but historians use the term more precisely. Some writers include the periods of the Greek-speaking Mycenaean civilization that collapsed about 1150 B.C.E., though most would argue that the influential Minoan culture was so different from later Greek cultures that it should be classed separately.

In the modern Greek schoolbooks, "ancient times" is a period of about 900 years, from the catastrophe of Mycenae until the conquest of the country by the Romans, that is divided in four periods, based on styles of art as much as culture and politics. The historical line starts with Greek Dark Ages (1100–800 B.C.E.). In this period, artists used geometrical schemes such as squares, circles, and lines to decorate amphoras and other pottery. The archaic period (800–500 B.C.E.) represents those years when the artists made larger free-standing sculptures in stiff, hieratic poses with the dreamlike "archaic smile." In the classical period (500–323 B.C.E.), artists perfected the style that since has been taken as exemplary: "classical," such as the Parthenon. In the Hellenistic years that followed the conquests of Alexander the Great (323–146 B.C.E.), also known as Alexandrian, aspects of Hellenic civilization expanded to Egypt and Bactria.

Traditionally, the ancient Greek period was taken to begin with the date of the first Olympic Games in 776 B.C.E., but many historians now extend the term back to about 1000 B.C.E. The traditional date for the end of the ancient Greek period is the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E. The following period is classed Hellenistic or the integration of Greece into the Roman Republic in 146 B.C.E.

These dates are historians' conventions and some writers treat the ancient Greek civilization as a continuum running until the advent of Christianity in the third century.

The Early Greeks

The Greeks are believed to have migrated southward into the Balkan peninsula in several waves beginning in the late third millennium B.C.E., the last being the Dorian invasion. Proto-Greek is assumed to date to some time between the twenty-third and seventeenth centuries B.C.E. The period from 1600 B.C.E. to about 1100 B.C.E. is called Mycenaean Greece, which is known for the reign of King Agamemnon and the wars against Troy as narrated in the epics of Homer. The period from 1100 B.C.E. to the eighth century B.C.E. is a "Dark Age" from which no primary texts survive, and only scant archaeological evidence remains. Secondary and tertiary texts such as Herodotus' Histories, Pausanias’ Description of Greece, Diodorus' Bibliotheca, and Jerome's Chronicon, contain brief chronologies and king lists for this period. The history of ancient Greece is often taken to end with the reign of Alexander the Great, who died in 323 B.C.E.

Any history of ancient Greece requires a cautionary note on sources. Those Greek historians and political writers whose works have survived, notably Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Demosthenes, Plato, and Aristotle, were mostly either Athenian or pro-Athenian. That is why more is known about the history and politics of Athens than of any other city, and why almost nothing is known about some cities' histories. These writers, furthermore, concentrate almost wholly on political, military, and diplomatic history, and ignore economic and social history. All histories of ancient Greece have to contend with these limits in their sources.

Minoans

The Minoans were a group of people who lived on the island of Crete in the eastern Mediterranean Sea during the Bronze Age. They are named after the famous King Minos, said to be the son of Zeus. Several "palace" settlements started to appear on the island around 2000 B.C.E., the most famous of which is the city of Knossos. Their writing is called Linear A. The Minoan settlements were discovered by the British archaeologist Arthur Evans in 1900. Little is known about Minoan life and culture.

Minoan art is very unique and easily recognizable. Wall frescos are frequent and often portray nautical themes with ships and dolphins. Also, in Knossos there are many images and statues of bull horns and female figures, over which scholars debate the meaning.

The myth of King Minos and the Minotaur is a well-known early Greek myth. Minos was said to be the son of Zeus and Europa. In order to ensure his claim of the domain over Crete and Knossos, he asked Poseidon for affirmation of his rule in return for a sacrifice. Poseidon sent down a bull as a symbol, but Minos did not hold up his end of the bargain. As punishment, Poseidon forced Minos' wife, Pasiphae, to lust after a bull. She mated with a bull by hiding in an artificial cow and gave birth to the half-bull, half-human Minotaur. Ashamed of this offspring, Minos shut him away in a maze called the Labyrinth. Later, Theseus slew the Minotaur to save his city, Thebes.

Mycenaeans

The Mycenaeans are thought to have developed after the Minoan settlements on Crete were destroyed. Mycenae, the city after which the people are named, is located on mainland Greece, on the Peloponnesian peninsula.

The rise of Hellas

In the eighth century B.C.E., Greece began to emerge from the Dark Ages that followed the fall of the Mycenaean civilization. Literacy had been lost and the Mycenaean script forgotten, but the Greeks created the Greek alphabet most likely by modifying the Phoenician alphabet. From about 800 B.C.E., written records begin to appear. Greece was divided into many small self-governing communities, a pattern dictated by Greek geography, where every island, valley, and plain is cut off from its neighbors by the sea or mountain ranges.

As Greece progressed economically, its population grew beyond the capacity of its limited arable land (according to Mogens Herman Hansen, the population of ancient Greece increased by a factor larger than ten during the period from 800 B.C.E. to 350 B.C.E., increasing from a population of 700,000 to a total estimated population of 8 to 10 million.)[1] From about 750 B.C.E., the Greeks began 250 years of expansion, settling colonies in all directions. To the east, the Aegean coast of Asia Minor was colonized first, followed by Cyprus and the coasts of Thrace, the Sea of Marmara, and south coast of the Black Sea. Eventually Greek colonization reached as far northeast as present-day Ukraine. To the west, the coasts of Illyria, Sicily, and southern Italy were settled, followed by the south coast of France, Corsica, and even northeastern Spain. Greek colonies were also founded in Egypt and Libya. Modern Syracuse, Naples, Marseille, and Istanbul had their beginnings as the Greek colonies Syracusa, Neapolis, Massilia, and Byzantium, respectively.

By the sixth century B.C.E., the Greek world had become a cultural and linguistic area much larger than the geographical area of present Greece. Greek colonies were not politically controlled by their founding cities, although they often retained religious and commercial links with them. The Greeks both at home and abroad organized themselves into independent communities, and the city (polis) became the basic unit of Greek government.

In this period, a huge economic development occurred in Greece and its overseas colonies, with the growth of commerce and manufacture. There also was a large improvement in the living standards of the population. Some studies estimate that the average size of the Greek household, in the period from 800 B.C.E. to 300 B.C.E., increased five times, which indicates a large increase in the average income of the population.

By the economic height of ancient Greece, in the fourth century B.C.E., Greece was the most advanced economy in the world. According to some economic historians, it was one of the most advanced pre-industrial economies. This is demonstrated by the average daily wage of the Greek worker, it was, in terms of grain (about 13 kg), more than 4 times the average daily wage of the Egyptian worker (about 3 kg).

Social and political conflict

The Greek cities were originally monarchies, although many of them were very small and the term king (basileus) for their rulers is misleadingly grand. In a country always short of farmland, power rested with a small class of landowners, who formed a warrior aristocracy fighting frequent petty inter-city wars over land and rapidly ousting the monarchy. About this time, the rise of a mercantile class (shown by the introduction of coinage in about 680 B.C.E.) introduced class conflict into the larger cities. From 650 B.C.E. onwards, the aristocracies had to fight not to be overthrown and replaced by populist leaders called tyrants (tyrranoi), a word that did not necessarily have the modern meaning of oppressive dictators.

By the sixth century B.C.E. several cities had emerged as dominant in Greek affairs: Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes. Each of them had brought the surrounding rural areas and smaller towns under their control, and Athens and Corinth had become major maritime and mercantile powers as well. Athens and Sparta developed a rivalry that dominated Greek politics for generations.

In Sparta, the landed aristocracy retained their power, and the constitution of Lycurgus (about 650 B.C.E.) entrenched their power and gave Sparta a permanent militarist regime under a dual monarchy. Sparta dominated the other cities of the Peloponnese with the sole exceptions of Argus and Achaia.

In Athens, by contrast, the monarchy was abolished in 683 B.C.E., and reforms of Solon established a moderate system of aristocratic government. The aristocrats were followed by the tyranny of Pisistratus and his sons, who made the city a great naval and commercial power. When the Pisistratids were overthrown, Cleisthenes established the world's first democracy (500 B.C.E.), with power being held by an assembly of all the male citizens. But it must be remembered that only a minority of the male inhabitants were citizens, excluding slaves, freedmen, and non-Athenians.

The Persian Wars

In Ionia (the modern Aegean coast of Turkey), the Greek cities, which included great centers such as Miletus and Halicarnassus, were unable to maintain their independence and came under the rule of the Persian Empire in the mid-sixth century B.C.E. In 499 B.C.E., the Greeks rose in the Ionian Revolt, and Athens and some other Greek cities went to their aid.

In 490 B.C.E., the Persian Great King, Darius I, having suppressed the Ionian cities, sent a fleet to punish the Greeks. The Persians landed in Attica, but were defeated at the Battle of Marathon by a Greek army led by the Athenian general Miltiades. The burial mound of the Athenian dead can still be seen at Marathon.

Ten years later, Darius's successor, Xerxes I, sent a much more powerful force by land. After being delayed by the Spartan King Leonidas I at the Battle of Thermopylae, Xerxes advanced into Attica, where he captured and burned Athens. But the Athenians had evacuated the city by sea, and under Themistocles they defeated the Persian fleet at the Battle of Salamis. A year later, the Greeks, under the Spartan Pausanius defeated the Persian army at Plataea.

The Athenian fleet then turned to chasing the Persians out of the Aegean Sea, and in 478 B.C.E. they captured Byzantium. In the course of doing so, Athens enrolled all the island states and some mainland allies into an alliance, called the Delian League because its treasury was kept on the sacred island of Delos. The Spartans, although they had taken part in the war, withdrew into isolation after it, allowing Athens to establish unchallenged naval and commercial power.

Dominance of Athens

The Persian Wars ushered in a century of Athenian dominance of Greek affairs. Athens was the unchallenged master of the sea, and also the leading commercial power, although Corinth remained a serious rival. The leading statesman of this time was Pericles, who used the tribute paid by the members of the Delian League to build the Parthenon and other great monuments of classical Athens. By the mid-fifth century B.C.E., the league had become an Athenian Empire, symbolized by the transfer of the league's treasury from Delos to the Parthenon in 454 B.C.E.

The wealth of Athens attracted talented people from all over Greece, and also created a wealthy leisure class who became patrons of the arts. The Athenian state also sponsored learning and the arts, particularly architecture. Athens became the center of Greek literature, philosophy, and the arts. Some of the greatest names of Western cultural and intellectual history lived in Athens during this period: the dramatists Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Euripides, and Sophocles, the philosophers Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates, the historians Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon, the poet Simonides, and the sculptor Pheidias. The city became, in Pericles's words, "the school of Hellas."

The other Greek states at first accepted Athenian leadership in the continuing war against the Persians, but after the fall of the conservative politician Cimon in 461 B.C.E., Athens became an increasingly open imperialist power. After the Greek victory at the Battle of the Eurymedon in 466 B.C.E., the Persians were no longer a threat, and some states, such as Naxos, tried to secede from the league, but were forced to submit. The new Athenian leaders, Pericles and Ephialtes let relations between Athens and Sparta deteriorate, and in 458 B.C.E., war broke out. After some years of inconclusive war, a 30-year peace was signed between the Delian League and the Peloponnesian League (Sparta and her allies). This coincided with the last battle between the Greeks and the Persians, a sea battle off Salamis in Cyprus, followed by the Peace of Callias (450 B.C.E.) between the Greeks and Persians.

The Peloponnesian War

In 431 B.C.E., war broke out again between Athens and Sparta and its allies. The immediate causes of the Peloponnesian War vary from account to account. However, three causes are fairly consistent among the ancient historians, namely Thucydides and Plutarch. Prior to the war, Corinth and one of its colonies, Corcyra (modern-day Corfu), got into a dispute in which Athens intervened. Soon after, Corinth and Athens argued over control of Potidaea (near modern-day Nea Potidaia), eventually leading to an Athenian siege of the Potidaea. Finally, Athens issued a series of economic decrees known as the "Megarian Decrees" that placed economic sanctions on the Megarian people. Athens was accused by the Peloponnesian allies of violating the Thirty Years Peace through all of the aforementioned actions, and Sparta formally declared war on Athens.

It should be noted that many historians consider these simply to be the immediate causes of the war. They would argue that the underlying cause was the growing resentment of Sparta and its allies at the dominance of Athens over Greek affairs. The war lasted 27 years, partly because Athens (a naval power) and Sparta (a land-based military power) found it difficult to come to grips with each other.

Sparta's initial strategy was to invade Attica, but the Athenians were able to retreat behind their walls. An outbreak of plague in the city during the siege caused heavy losses, including the death of Pericles. At the same time, the Athenian fleet landed troops in the Peloponnese, winning battles at Naupactus (429 B.C.E.) and Pylos (425 B.C.E.). But these tactics could bring neither side a decisive victory.

After several years of inconclusive campaigning, the moderate Athenian leader Nicias concluded the Peace of Nicias (421 B.C.E.).

In 418 B.C.E., however, hostility between Sparta and the Athenian ally Argos led to a resumption of fighting. At Mantinea, Sparta defeated the combined armies of Athens and her allies. The resumption of fighting brought the war party, led by Alcibiades, back to power in Athens. In 415 B.C.E., Alcibiades persuaded the Athenian Assembly to launch a major expedition against Syracuse, a Peloponnesian ally in Sicily. Though Nicias was a skeptic about the Sicilian Expedition, he was appointed along Alcibiades to lead the expedition. Due to accusations against him, Alcibiades fled to Sparta, where he persuaded Sparta to send aid to Syracuse. As a result, the expedition was a complete disaster and the whole expeditionary force was lost. Nicias was executed by his captors.

Sparta had now built a fleet (with the help of the Persians) to challenge Athenian naval supremacy, and had found a brilliant military leader in Lysander, who seized the strategic initiative by occupying the Hellespont, the source of Athens' grain imports. Threatened with starvation, Athens sent its last remaining fleet to confront Lysander, who decisively defeated them at Aegospotami (405 B.C.E.). The loss of her fleet threatened Athens with bankruptcy. In 404 B.C.E., Athens sued for peace, and Sparta dictated a predictably stern settlement: Athens lost her city walls, her fleet, and all of her overseas possessions. The anti-democratic party took power in Athens with Spartan support.

Spartan and Theban dominance

The end of the Peloponnesian War left Sparta the master of Greece, but the narrow outlook of the Spartan warrior elite did not suit them to this role. Within a few years, the democratic party regained power in Athens and other cities. In 395 B.C.E., the Spartan rulers removed Lysander from office, and Sparta lost her naval supremacy. Athens, Argos, Thebes, and Corinth, the latter two formerly Spartan allies, challenged Spartan dominance in the Corinthian War, which ended inconclusively in 387 B.C.E. That same year, Sparta shocked Greek opinion by concluding the Treaty of Antalcidas with Persia, by which they surrendered the Greek cities of Ionia and Cyprus; thus they reversed a hundred years of Greek victories against Persia. Sparta then tried to further weaken the power of Thebes, which led to a war where Thebes formed an alliance with the old enemy, Athens.

The Theban generals Epaminondas and Pelopidas won a decisive victory at Leuctra (371 B.C.E.). The result of this battle was the end of Spartan supremacy and the establishment of Theban dominance, but Athens herself recovered much of her former power because the supremacy of Thebes was short-lived. With the death of Epaminondas at Mantinea (362 B.C.E.) the city lost its greatest leader, and his successors blundered into an ineffectual ten-year war with Phocis. In 346 B.C.E., the Thebans appealed to Philip II of Macedon to help them against the Phocians, thus drawing Macedon into Greek affairs for the first time.

The rise of Macedon

The Kingdom of Macedon was formed in the seventh century B.C.E. It played little part in Greek politics before the fifth century B.C.E. In the beginning of the fourth century B.C.E., King Philip II of Macedon, an ambitious man who had been educated in Thebes, wanted to play a larger role. In particular, he wanted to be accepted as the new leader of Greece in recovering the freedom of the Greek cities of Asia from Persian rule. By seizing the Greek cities of Amphipolis, Methone, and Potidaea, he gained control of the gold and silver mines of Macedonia. This gave him the resources to realize his ambitions.

Philip established Macedonian dominance over Thessaly (352 B.C.E.) and Thrace, and by 348 B.C.E. he controlled everything north of Thermopylae. He used his great wealth to bribe Greek politicians, creating a "Macedonian party" in every Greek city. His intervention in the war between Thebes and Phocis brought him great recognition, and gave him his opportunity to become a power in Greek affairs. Against him, the Athenian leader Demosthenes, in a series of famous speeches (philippics), roused the Athenians to resist Philip's advance.

In 339 B.C.E., Thebes and Athens formed an alliance to resist Philip's growing influence. Philip struck first, advancing into Greece and defeating the allies at Chaeronea in 338 B.C.E. This traditionally marks the start of the decline of the city-state institution, though they mostly survived as independent states until Roman times.

Philip tried to win over the Athenians by flattery and gifts, but these efforts met with limited success. He organized the cities into the League of Corinth, and announced that he would lead an invasion of Persia to liberate the Greek cities and avenge the Persian invasions of the previous century. But before he could do so, he was assassinated (336 B.C.E.).

The conquests of Alexander

Philip was succeeded by his 20-year-old son Alexander, who immediately set out to carry out his father's plans. When he saw that Athens had fallen, he wanted to bring back the tradition of Athens by destroying the Persian king. He traveled to Corinth where the assembled Greek cities recognized him as leader of the Greeks, then set off north to assemble his forces. The core structure of his army was the hardy Macedonian mountain-fighter, but he bolstered his numbers and diversified his army with levies from all corners of Greece. He enriched his tactics and formation with Greek stratagem ranging from Theban cavalry structure to Spartan guerrilla tactics. His engineering and manufacturing were largely derived of Greek origin—involving everything from Archimedal siege-weaponry to Ampipholian ship-reinforcement. But while Alexander was campaigning in Thrace, he heard that the Greek cities had rebelled. He swept south again, captured Thebes, and razed the city to the ground. He left only one building standing, the house of Pindar, a poet who had written in favor of Alexander's ancestor, Alexander the First. This acted as a symbol and warning to the Greek cities that his power could no longer be resisted, while reminding them he would preserve and respect their culture if they were obedient.

In 334 B.C.E., Alexander crossed into Asia and defeated the Persians at the river Granicus. This gave him control of the Ionian coast, and he made a triumphal procession through the liberated Greek cities. After settling affairs in Anatolia, he advanced south through Cilicia into Syria, where he defeated Darius III at Issus (333 B.C.E.). He then advanced through Phoenicia to Egypt, which he captured with little resistance, the Egyptians welcoming him as a liberator from Persian oppression, and the prophesized son of Amun.

Darius was now ready to make peace and Alexander could have returned home in triumph, but Alexander was determined to conquer Persia and make himself the ruler of the world. He advanced northeast through Syria and Mesopotamia, and defeated Darius again at Gaugamela (331 B.C.E.). Darius fled and was killed by his own followers. Alexander found himself the master of the Persian Empire, occupying Susa and Persepolis without resistance.

Meanwhile, the Greek cities were making renewed efforts to escape from Macedonian control. At Megalopolis in 331 B.C.E., Alexander's regent Antipater defeated the Spartans, who had refused to join the Corinthian League or recognize Macedonian supremacy.

Alexander pressed on, advancing through what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan to the Indus River valley and by 326 B.C.E. he had reached Punjab. He might well have advanced down the Ganges to Bengal had not his army, convinced they were at the end of the world, refused to go any further. Alexander reluctantly turned back, and died of a fever in Babylon in 323 B.C.E.

Alexander's empire broke up soon after his death, but his conquests permanently changed the Greek world. Thousands of Greeks traveled with him or after him to settle in the new Greek cities he had founded as he advanced, the most important being Alexandria in Egypt. Greek-speaking kingdoms in Egypt, Syria, Persia, and Bactria were established. The knowledge and cultures of east and west began to permeate and interact. The Hellenistic age had begun.

Greek Society

The distinguishing features of ancient Greek society were the division between free and slave, the differing roles of men and women, the relative lack of status distinctions based on birth, and the importance of religion. The way of life of the Athenians was common in the Greek world compared to Sparta's special system.

Social Structure

Only free people could be citizens entitled to the full protection of the law in a city-state. In most city-states, unlike Rome, social prominence did not allow special rights. For example, being born in a certain family generally brought no special privileges. Sometimes families controlled public religious functions, but this ordinarily did not give any extra power in the government. In Athens, the population was divided into four social classes based on wealth. People could change classes if they made more money. In Sparta, all male citizens were given the title of "equal" if they finished their education. However, Spartan kings, who served as the city-state's dual military and religious leaders, came from two families.

Slaves had no power or status. They had the right to have a family and own property; however they had no political rights. By 600 B.C.E., chattel slavery had spread in Greece. By the fifth century B.C.E., slaves made up one-third of the total population in some city-states. Slaves outside of Sparta almost never revolted because they were made up of too many nationalities and were too scattered to organize.

Most families owned slaves as household servants and laborers, and even poor families might have owned one or two slaves. Owners were not allowed to beat or kill their slaves. Owners often promised to free slaves in the future to encourage slaves to work hard. Unlike in Rome, slaves who were freed did not become citizens. Instead, they were mixed into the population of metics, which included people from foreign countries or other city-states who were officially allowed to live in the state.

City-states also legally owned slaves. These public slaves had a larger measure of independence than slaves owned by families, living on their own and performing specialized tasks. In Athens, public slaves were trained to look out for counterfeit coinage, while temple slaves acted as servants of the temple's deity.

Sparta had a special type of slaves called helots. Helots were Greek war captives owned by the state and assigned to families. Helots raised food and did household chores so that women could concentrate on raising strong children while men could devote their time to training as hoplites (citizen-soldiers). Their masters treated them harshly and helots often revolted.

Daily Life

For a long time, the way of life in the Greek city-states remained the same. People living in cities resided in low apartment buildings or single-family homes, depending on their wealth. Residences, public buildings, and temples were situated around the agora. Citizens also lived in small villages and farmhouses scattered across the state's countryside. In Athens, more people lived outside the city walls than inside (it is estimated that from a total population of 400,000 people, 160,000 people lived inside the city, which is a large rate of urbanization for a pre-industrial society).

A common Greek household was simple if compared to a modern one, containing bedrooms, storage rooms, and a kitchen situated around a small inner courtyard. Its average size, about 230 square meters in the fourth century B.C.E., was much larger than the houses of other ancient civilizations.

A household consisted of a single set of parents and their children, but generally no relatives. Men were responsible for supporting the family by work or investments in land and commerce. Women were responsible for managing the household's supplies and overseeing slaves, who fetched water in jugs from public fountains, cooked, cleaned, and looked after babies. Men kept separate rooms for entertaining guests, because male visitors were not permitted in rooms where women and children spent most of their time. Wealthy men would sometimes invite friends over for a symposium. Light came from olive oil lamps, while heat came from charcoal braziers. Furniture was simple and sparse, which included wooden chairs, tables, and beds.

The majority of Greeks worked in agriculture, probably 80 percent of the entire population, which is similar to all pre-industrial civilizations. The soil in Greece was poor and rainfall was very unpredictable. Research suggests the climate has changed little since ancient times, so frequent weeding and turning of soil was needed. Oxen might have helped with plowing, however most tasks would have been done by hand. The Greek farmer would ideally plan for a surplus of crops to contribute to feasts and to buy pottery, fish, salt, and metals.

Ancient Greek food was simple as well. Poor people mainly ate barley porridge flavored with onions, vegetables, and cheese or olive oil. Few people ever ate meat regularly, except for the free distributions from animal sacrifices at state festivals. Sheep when eaten was mutton: "Philochorus [third century B.C.E.] relates that a prohibition was issued at Athens against anyone tasting lamb which had not been shorn…[2] Bakeries sold fresh bread daily, while small stands offered snacks. Wine diluted with water was a favored beverage.

Greek clothing changed little over time. Both men and women wore loose Peplos and Chitons. The tunics often had colorful designs and were worn cinched with a belt. People wore cloaks and hats in cold weather, and in warm weather sandals replaced leather boots. Women wore jewelry and cosmetics—especially powdered lead, which gave them a pale complexion. Men grew beards until Alexander the Great created a vogue for shaving.

To keep fit and to be ready for military service, men exercised daily. Almost every city-state had at least one gymnasium, a combination exercise building, running track, bathing facility, lecture hall, and park. In most cities (other than Sparta), gymnasia were open only to males, and exercise was taken in the nude. City-state festivals provided great amounts of entertainment. Gods were honored with competitions in music, drama, and poetry. Athenians boasted that their city hosted a festival nearly every other day. Huge Panhellenic festivals were held at Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and Isthmia. Athletes and musicians who won these competitions became rich and famous. The most popular and expensive competition was chariot racing.

Education

For most of Greek history, education was private, except in Sparta. During the Hellenistic period, some city-states established public schools. Only wealthy families could afford a teacher. Boys learned how to read, write, and quote literature. They also learned to sing and play one musical instrument and were trained as athletes for military service. They studied not for a job, but to become an effective citizen. Girls also learned to read, write, and do simple arithmetic so they could manage the household. They almost never received education after childhood.

A small number of boys continued their education after childhood; one example is the Spartans (with military education). A crucial part of a wealthy teenager's education was a loving mentor relationship with an elder. The teenager learned by watching his mentor talking about politics in the agora, helping him perform his public duties, exercising with him in the gymnasium, and attending symposia with him. The richest students continued their education to college, and went to a university in a large city. These universities were organized by famous teachers. Some of Athens' greatest universities included the Lyceum and the Academy.

Medicine

Medicine in ancient Greece was limited if compared to modern medicine. Hippocrates helped separate superstition from medical treatment in the fifth century B.C.E. Herbal remedies were used to reduce pain, and doctors were able to perform some surgery. But they had no cure for infections, so even healthy people could die quickly from disease at any age.

Galen (131–201 C.E.) built on the work of earlier Greek scholars, such as Herophilus of Chalcedon (335–280 B.C.E.) to become almost synonymous with Greek medical knowledge. He became physician to the Roman emperor, Marcus Aurelius. His message of observation and experimentation were largely lost, however, and his theories became dogma throughout the West. In the mid-sixteenth century, his message that observation and investigation were required for through medical research began to emerge, and modern methods of such research finally arose.

Mathematics

Ancient Greece produced an impressive list of mathematicians, perhaps the most famous of them being Euclid (also referred to as Euclid of Alexandria) (c. 325–265 B.C.E.) who lived in Alexandria in Hellenistic Egypt.

Philosophers

Among the most significant Greek philosophers were Socrates (470–399 B.C.E.), his pupil Plato (427–347 B.C.E.), and his pupil Aristotle (384–322 B.C.E.). Their focus was on reason, and their thought influenced Christian theology, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment. The Stoics, Epicureans, and the Skeptics were also very influential.

Art

The art of ancient Greece has exercised an enormous influence on the culture of many countries from ancient times until the present, particularly in the areas of sculpture and architecture. In the west, the art of the Roman Empire was largely derived from Greek models. In the east, Alexander the Great’s conquests initiated several centuries of exchange between Greek, central Asian, and Indian cultures, resulting in Greco-Buddhist art, with ramifications as far as Japan. Following the Renaissance in Europe, the humanist aesthetic and the high technical standards of Greek art inspired generations of European artists. Well into the nineteenth century, the classical tradition derived from Greece dominated the art of the Western world.

The ancient Greeks were especially skilled at sculpture. The Greeks thus decided very early on that the human form was the most important subject for artistic endeavor. Seeing their gods as having human form, there was no distinction between the sacred and the secular in art—the human body was both secular and sacred. A male nude could just as easily be Apollo or Heracles or that year's Olympic boxing champion. In the Archaic period, the most important sculptural form was the kouros (plural kouroi), the standing male nude. The kore (plural korai), or standing clothed female figure, was also common, but since Greek society did not permit the public display of female nudity until the fourth century B.C.E., the kore is considered to be of less importance in the development of sculpture.

Religion

It is perhaps misleading to speak of "Greek religion." In the first place, the Greeks did not have a term for "religion" in the sense of a dimension of existence distinct from all others, and grounded in the belief that the gods exercise authority over the fortunes of human beings and demand recognition as a condition for salvation. The Greeks spoke of their religious doings as ta theia (literally, "things having to do with the gods"), but this loose usage did not imply the existence of any authoritative set of "beliefs." Indeed, the Greeks did not have a word for "belief" in either of the two familiar senses. Since the existence of the gods was a given, it would have made no sense to ask whether someone "believed" that the gods existed. On the other hand, individuals could certainly show themselves to be more or less mindful of the gods, but the common term for that possibility was nomizein, a word related to nomos ("custom," "customary distribution," "law"); to nomizein, the gods were to be acknowledged by their rightful place in the scheme of things, and were to be given their due. Some bold individuals could nomizein the gods, but deny that they were due some of the customary observances. But these customary observances were so highly unsystematic that it is not easy to describe the ways in which they were normative for anyone.

First, there was no single truth about the gods. Although the different Greek peoples all recognized the 12 major gods (Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Ares, Hephaestus, Athena, Hermes, Dionysos, and Demeter), in different locations these gods had such different histories with the local peoples as often to make them rather distinct gods or goddesses. Different cities worshipped different deities, sometimes with epithets that specified their local nature; Athens had Athena; Sparta, Artemis; Corinth was a center for the worship of Aphrodite; Delphi and Delos had Apollo; Olympia had Zeus, and so on down to the smaller cities and towns. Identity of names was not even a guarantee of a similar cultus; the Greeks themselves were well aware that the Artemis worshipped at Sparta, the virgin huntress, was a very different deity from the Artemis who was a many-breasted fertility goddess at Ephesus. When literary works such as the Iliad related conflicts among the gods because their followers were at war on earth, these conflicts were a celestial reflection of the earthly pattern of local deities. Though the worship of the major deities spread from one locality to another, and though most larger cities boasted temples to several major gods, the identification of different gods with different places remained strong to the end.

Second, there was no single true way to live in dealing with the gods. "The things that have to do with the gods" had no fixed center, and responsibilities for these things had a variety of forms. Each individual city was responsible for its own temples and sacrifices, but it fell to the wealthy to sponsor the leitourgeiai (literally, "works for the people," from which the word "liturgy" derives)—the festivals, processions, choruses, dramas, and games held in honor of the gods. Phratries (members of a large hereditary group) oversaw observances that involved the entire group, but fathers were responsible for sacrifices in their own households, and women often had autonomous religious rites.

Third, individuals had a great deal of autonomy in dealing with the gods. After some particularly striking experience, they could bestow a new title upon a god, or declare some particular site as sacred (cf. Gen. 16:13–14, where Hagar does both). No authority accrued to the individual who did such a thing, and no obligation fell upon anyone else—only a new opportunity or possibility was added to the already vast and ill-defined repertoire for nomizeining the gods.

Finally, the lines between divinity and humanity were in some ways clearly defined, and in other ways ambiguous. Setting aside the complicated genealogies in which gods sired children upon human women and goddesses bore the children of human lovers, historical individuals could receive cultic honors for their deeds during life after their death—in other words, a hero cult. Indeed, even during life, victors at the Olympics, for instance, were considered to have acquired extraordinary power, and on the strength of their glory (kudos), would be chosen as generals in time of war. Itinerant healers and leaders of initiatory rites would sometimes be called in to a city to deliver it from disasters, without such a measure implying any disbelief in the gods or exaltation of such "saviors." To put it differently, sôteria ("deliverance," "salvation") could come from divine or human hands and, in any event, the Greeks offered cultic honors to abstractions like Chance, Necessity, and Luck, divinities that stood in ambiguous relation to the personalized gods of the tradition. All in all, there was no "dogma" or "theology" in the Greek tradition; no heresy, hypocrisy, possibility of schism, or any other social phenomenon articulated according to a background orientation created a codified order of religious understanding. Such variety in Greek religion reflects the long, complicated history of the Greek-speaking peoples.

Greek religion spans a period from Minoan and Mycenaean periods to the days of Hellenistic Greece and its ultimate conquest by the Roman Empire. Religious ideas continued to develop over this time; by the time of the earliest major monument of Greek literature, the Iliad attributed to Homer, a consensus had already developed about who the major Olympian gods were. Still, changes to the canon remained possible; the Iliad seems to have been unaware of Dionysus, a god whose worship apparently spread after it was written, and who became important enough to be named one of the 12 chief Olympian deities, ousting the ancient goddess of the hearth, Hestia. It has been written by scholars that Dionysus was a "foreign" deity, brought into Greece from outside local cults, external to Greece proper.

In addition to the local cults of major gods, various places like crossroads and sacred groves had their own tutelary spirits. There were often altars erected outside the precincts of the temples. Shrines like hermai were erected outside the temples as well. Heroes, in the original sense, were demigods or deified humans who were part of local legendary history; they too had local hero-cults, and often served as oracles for purposes of divination. What religion was, first and foremost, was traditional; the idea of novelty or innovation in worship was out of the question, almost by definition. Religion was the collection of local practices to honor the local gods.

The scholar, Andrea Purvis, has written on the private cults in ancient Greece as a traceable point for many practices and worship of deities.

A major function of religion was the validation of the identity and culture of individual communities. The myths were regarded by many as history rather than allegory, and their embedded genealogies were used by groups to proclaim their divine right to the land they occupied, and by individual families to validate their exalted position in the social order

Notes

- ↑ Mogens Herman Hansen, The Shotgun Method: The Demography of the Ancient Greek City-State Culture (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0826216670).

- ↑ Athenaeus, The Deipnosophists; Or, Banquet of the Learned, Volume 1 (Nabu Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1141969630) 1.16.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists; Or, Banquet of the Learned, Volume 1. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1141969630

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987. ISBN 0674362810

- Buxton, Richard. The Complete World of Greek Mythology. London: Thames and Hudson, 2004. ISBN 0500251215

- Cook, Arthur Bernard. Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, 3 vols. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2010. Vol 1 ISBN 978-1108021227; Vol 2 part 1 ISBN 978-1108021302; Vol 2 part 2 ISBN 978-1108021234

- Freeman, Charles. Egypt, Greece and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0199263647

- Freeman, Charles. The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World. New York, NY: Penguin, 2000. ISBN 014029323X

- Hansen, Mogens Herman. The Shotgun Method: The Demography of the Ancient Greek City-State Culture. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0826216670

- Mikalson, Jon D. Athenian Popular Religion. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1983. ISBN 0807841943

External links

All links retrieved June 19, 2021.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 19:42:31 | 373 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Ancient_Greece | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF