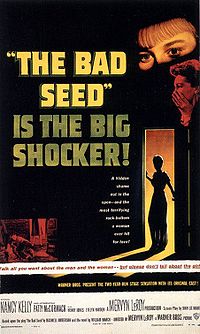

The Bad Seed

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | The Bad Seed | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Mervyn LeRoy |

| Produced by | Mervyn LeRoy |

| Written by | William March (novel) Maxwell Anderson (stage play) John Lee Mahin (script) |

| Starring | Nancy Kelly Patty McCormack Eileen Heckart Henry Jones Evelyn Varden |

| Music by | Alex North |

| Cinematography | Harold Rosson |

| Editing by | Warren Low |

| Distributed by | Warner Brothers |

| Release date(s) | September 12, 1956 |

| Running time | 129 min |

| Country | USA |

| Language | English |

| Allmovie profile | |

| IMDb profile | |

Contents

- 1 Plot

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 The Picnic

- 1.3 The First Suspicions

- 1.4 Revealing Evidence

- 1.5 Leroy Presses His Luck

- 1.6 The Bad Seed Theory

- 1.7 Christine's History

- 1.8 Attempt to Destroy Evidence

- 1.9 Leroy Pushes Too Far

- 1.10 Hortense' Demand

- 1.11 Par-Broiled Handyman

- 1.12 Attempted Murder-Suicide

- 1.13 Retribution

- 1.14 The Casting Call

- 2 Cast

- 3 Themes

- 4 Alteration of the ending

- 5 Awards and Nominations

Plot[edit]

Introduction[edit]

Lovely, well-to-do Christine Bravo Penmark has everything: a loving, well-paid husband with a respectable career (as an Air Force colonel, no less), a swank apartment in a respectable part of town, and an adorable, cherubic eight-year-old daughter. But as Col. Kenneth Penmark leaves for an assignment in Washington, DC, the strains that have lurked beneath the surface of the Penmark household now begin to manifest. For example, her daughter Rhoda gives every indication of being a grasping, greedy child, whom their landlady, Monica Breedlove, indulges with extravagant presents that Rhoda gives some indication of not being entirely satisfied with. For another, Rhoda protests loudly and resentfully when reminded that she had lost a penmanship competition, saying that she ought to have won first place, and the medal that goes with that honor.

The apartment-house handyman, Leroy Jessup, presents another complication. Though an adult, he seems to have an eight-year-old mind himself. He is also mean and spiteful, and regularly spars with Rhoda.

The Picnic[edit]

Rhoda leaves for a school picnic, wearing two shoes that have been modified with iron plates to make them sound like tap shoes. As she leaves, Leroy sprays her shoes with the garden hose, earning a stern reprimand from Monica. Leroy nurses resentment of Mrs. Breedlove, a lustful attitude toward Christine, and a clear enmity toward Rhoda. His attitude and behavior clearly indicates that he is thinking as a child and is thinking of Rhoda on her level, not on an adult level.

At the picnic, Christine tries to sound out Claudia Fern, the headmistress of Rhoda's school, about how Rhoda is fitting in and getting along. Miss Fern at first is effusive in her praise of Rhoda but then becomes evasive and abruptly excuses herself. Christine confesses at this point that Rhoda seems overly mature for her age, in a "disturbing" manner.

That afternoon, Christine entertains her "psychiatry club," at which Monica fairly boasts of having been under analysis by some of the most droppable names in the profession of psychiatry. (That she could actually have been a patient of Sigmund Freud, as she boasts, is a stretch, and her fellow clubbers seem to know it.) Then, as the club starts to discuss a case of a recently convicted serial murderess, Christine finds the conversation disturbing, prompting Monica to tease her about it. The conversation then continues onto the case of one Bessie Denker, a name that Christine recognizes but won't elaborate on.

In the middle of this conversation, someone turns on the radio, and the announcer gives a shocking report: that Claude Daigle, a fellow student of Rhoda's, has drowned on an old, rickety pier that the students had been forbidden to play on or near. As expected, the school bus brings Rhoda home early—and Rhoda, far from being in any to-be-expected state of shock, seems to care nothing about the death of her classmate, and casually asks for a peanut-butter sandwich and a glass of milk, and then goes out roller-skating. The one adult who takes the most notice of Rhoda's casual attitude is the handyman, Leroy. He says flat-out that she's not even sorry that he died, and Rhoda half-innocently, half-sardonically asks why she should feel sorry. As she skates away, Leroy forms a resolve to find something to scare her with.

The First Suspicions[edit]

A few days later, Claudia Fern comes to visit Christine, and to reveal some startling information: that Rhoda was the last student to see Claude Daigle alive, and that Claude's penmanship medal, which he had worn to the picnic, was now missing. Miss Fern also reveals that Rhoda had been pestering Claude all morning, trying to snatch his medal from him. Furthermore, Miss Fern reveals that a lifeguard had shouted a warning to a girl answering to Rhoda's description, as she was coming off the wharf.

Christine now remembers that Claudia Fern and her sisters never asked Christine to pay for a share of the flowers for Claude Daigle's funeral, and Miss Fern states that she thought that Christine would prefer to send flowers individually. Now Christine asks flatly why Miss Fern would take that attitude, and ask Christine Penmark about the missing medal. In reply, Miss Fern reveals what she had earlier not wanted to discuss with Christine: that Rhoda has no sense of fair play, is a sore loser, and has earned the enmity of all the other pupils in the school. Furthermore, Miss Fern announces that Rhoda will not be welcome when school takes up again in the following fall. This prompts Christine to ask Miss Fern flat-out whether she supposes that Rhoda had anything to do with Claude's death. Shocked, Miss Fern disclaims any such suspicion, but her behavior indicates that, whether she harbored such a suspicion or not, her sisters do.

Their conversation is interrupted when Hortense Daigle, the dead boy's mother, stumbles into the apartment, drunk and barely able to walk in a straight line, followed closely by Henry Daigle, her embarrassed husband. Mrs. Daigle sarcastically observes that Christine is her social superior, an "honor" that Christine hastily disclaims, and then comes to the point of her visit: she demands to know what became of the penmanship medal, and what Miss Fern, concerned as she probably is with liability issues, won't reveal. Mrs. Daigle also reveals that Claude, when found, had bruises on his hand and a crescent-moon-shaped wound on his forehead. In the end Mrs. Daigle becomes terrifically angry, and then almost collapses in tears, allowing her otherwise-ineffectual husband to lead her away. After Hortense leaves, Christine and Miss Fern have a tearful parting. Shortly after this, Col. Penmark calls to ask about the accident, and to reveal that his Washington assignment will last at least another four weeks.

Revealing Evidence[edit]

When Monica calls and asks Christine to lend her a locket that she had given Rhoda, so that she can have its gemstone changed, Christine is horrified to find the penmanship medal in Rhoda's little "treasure chest." She then shows the medal to Rhoda and demands that Rhoda explain how she came by the medal. Rhoda at first tries to change the subject, then denies that she had had the medal, then tells a variety of stories that Christine recognizes as false almost at once, and finally says that she had somehow persuaded Claude to let her hold the medal, and then had gone out onto the pier and fallen in later on. In between these activities, Rhoda indulges in a bit of flattery that now seems anything but flattering. Then Christine recalls a fatal accident that had happened to a neighbor in Wichita, KS, an accident by which Rhoda came into possession of a keepsake belonging to the neighbor. Christine finally announces her intention to call Miss Fern, intending to surrender the medal, but Rhoda, in a frightened tone, begs her not to, saying that the school officials don't like her and were persecuting her. Miss Fern is not available, and Rhoda seems to care most of all about retaining the medal, insisting that she, not Claude, had actually earned it.

Leroy Presses His Luck[edit]

Back in Washington, Col. Penmark buys an expensive children's tea set for Rhoda and has it shipped to Rhoda, packed in excelsior. Rhoda goes out to play with it, and takes the packing material with her. Leroy sees her at play, and begins his scare campaign by accusing her of beating Claude Daigle with a stick and saying that she could never clean a murder weapon enough to remove all trace of blood, that the police have "stick bloodhounds" that can find a thrown-away stick in any forest, and that the police laboratory will sprinkle "blood powder" on a blood-soaked stick and make it turn blue. Rhoda, for her part, gives Leroy the excelsior, saying that she knows about the bed of excelsior that Leroy has made for himself so that he can sleep on the job in the furnace room without being caught. Nor is she afraid of Leroy's accusations, saying that he made them all up. Christine catches Leroy talking to Rhoda and warns him never to speak to Rhoda again, or she will report him to Monica Breedlove.

When Rhoda comes back into the house, she asks her mother about police tests for blood. Christine offers to ask Miss Fern about it, but again Rhoda does not want Christine to ask Miss Fern any such thing.

The Bad Seed Theory[edit]

Christine instructs Rhoda to go up to Mrs. Breedlove's apartment for dinner, while the famous psychiatrist Reginald Tasker dines in the Penmark apartment with the local "psychiatry club." Mr. Tasker reveals that he has great respect for Christine's father, Richard Bravo, who had been quite an authority on crime and criminals in his younger days. Tasker and Bravo engage in good-natured professional sparring, and also discuss Christine Penmark's own dreams of writing a murder mystery. Christine asks Tasker whether children ever commit murder, and Tasker says that they do, and even that many adult criminals begin their careers in childhood. Christine insists that criminals are made in bad environments, but Tasker insists that some criminals are born that way, that they are "bad seeds," possessing atavistic, consciousless minds, and even that one might inherit a tendency to criminality. Richard Bravo refuses to accept such a theory, but Tasker politely stands by his theory, and even states that a child criminal would not present a sour countenance at all, but would instead present a quite convincing "normal" and "innocent" manner.

Then the conversation turns to the case of Bessie Denker, one of Richard Bravo's own case-history subjects. Bravo wants to avoid the subject, but Christine insists, and Tasker reveals that Ms. Denker vanished without a trace before the authorities could make an arrest. Tasker even remembers that Ms. Denker left a child behind, a part of the story that Bravo hastily denies. Shortly after making this revelation, Tasker leaves.

Christine's History[edit]

Now that Christine and her father are alone together, Mr. Bravo challenges Christine with the worry that shows plainly on her countenance. Now Christine starts to talk freely of her fear of having been an adopted child, and not the actual daughter of Richard Bravo and his wife. Christine also says that her concerns about Rhoda have prompted a return of her old fear. She mentions a recurring nightmare that she had always talked to Richard about, but Mr. Bravo clearly does not want to discuss it, and especially does not want Christine to lend credence to the inherited-criminality theory.

But now Mr. Bravo reveals that he did find Christine in "a very strange place." Then Christine reveals her recurring nightmare, about living in a farmhouse with her brother and a very beautiful lady, then not having a brother anymore, then being terrified of being in the room, then being outside in an orchard. Finally she remembers the name she originally had: her name was not Christine Bravo at all, but Ingold Denker, Bessie Denker's daughter.

This, then, is the truth: Richard Bravo found Ingold Denker, whom he renamed Christine, in the orchard on the Denker farm after Bessie Denker had fled. But Christine now feels that she would have done better to die, because she is afraid that she inherited a tendency to extreme criminality from her real mother, Bessie Denker—and passed this on to her own daughter, Rhoda Penmark.

At this moment, Monica Breedlove returns with Rhoda. Rhoda greets her grandfather cheerfully, but now Richard Bravo takes a long, hard look at his granddaughter, though he will not explain his misgivings. Bravo agrees to stay in a spare room in Monica's apartment overnight.

Attempt to Destroy Evidence[edit]

Later, Christine catches Rhoda trying to dispose of something in a paper bag. Rhoda doesn't want to reveal the contents of the bag, so Christine struggles with Rhoda and forces her to reveal what she had been trying to dispose of: her shoes with the iron half-moon reinforcements. Now Rhoda knows the horrible truth and extracts a confession from her: that Rhoda killed Claude Daigle by beating him with her toe shoes, after he had refused to let her handle his penmanship medal. After the first blow, Claude surrendered the medal, and then tried to escape, and Rhoda struck him again, and again, until he fell in the water. When he tried to climb back onto the wharf, Rhoda beat the backs of his hands with her shoes to make him let go, and so he drowned. Rhoda also confesses something else: that she had in fact deliberately caused their neighbor in Wichita to fall on some ice. Christine, totally distraught, instructs Rhoda to throw the shoes into the incinerator slot and say nothing to anyone. Rhoda again asks about the medal, and Christine half-promises not to give the medal back to Miss Fern.

Leroy Pushes Too Far[edit]

The next morning, Richard Bravo leaves, and Leroy again tries to tease Rhoda. This time Leroy says that if the police find the stick with which she killed Claude Daigle, they'll sentence her to death in the electric chair, and even that the police have his-and-her child-sized electric chairs. Next, Leroy says that he hasn't seen her in her tap shoes, and now says that he knows that she hit Claude Daigle with the shoes, and even that he has retrieved them from the incinerator. That last boast causes Rhoda to take alarm and demand that Leroy return the shoes. At last Leroy has found something to scare her with, and he presses his point—and finally realizes that she really did the deed, and that's the reason why she is scared and is demanding the return of the shoes.

In fact, Leroy did not retrieve the shoes when he said he did, but after Christine chases Leroy away from Rhoda a second time, Leroy opens the incinerator and finds the shoes, but is now too afraid to say anything. Christine, for her part, reprimands Rhoda for talking about this subject after they had agreed never to speak of it to anyone.

Hortense' Demand[edit]

When Monica calls to give Rhoda the locket, after it has been modified, Rhoda asks permission to catch the ice-cream man and buy a popsicle. On her way, Rhoda tries to steal several matches. Christine tells her to replace them, but Rhoda manages to hide two of them. When Rhoda leaves, Monica probes Christine, knowing that something is troubling her, but not knowing what. Monica offers to give Christine some sleeping pills to help her sleep. Christine collapses in a pool of tears, but still is afraid to tell Monica anything. At that moment, Hortense Daigle, drunk as before, returns to the apartment, seeking yet another confrontation, not only with Christine, but this time also with Rhoda. Hortense has by now tried to talk to Miss Fern a dozen times without result, and has also spoken to the lifeguard from the fatal picnic. What she now knows makes her firmly suspect Rhoda of something, though she is not even sure herself what she suspects. Hortense does not succeed in getting the information she seeks, or in scaring Rhoda (because Monica hastily takes Rhoda away on a pretext). But she does succeed in frightening Christine very badly before her husband finally shows up to take her home again.

Par-Broiled Handyman[edit]

After Hortense leaves, Christine starts to call Col. Penmark, but despairs of having anything constructive to tell him. Monica returns and reveals that she allowed Rhoda to go out and buy another popsicle. Rhoda comes back into the apartment, excuses herself into the music room, and starts again to play her favorite tune, "Au clair de la lune," on the piano over and over. While she is playing, Christine hears a man's voice from below, screaming at the top of his voice for someone to let him out. She then hears a desperate knocking from inside the sloping cellar door, and then sees a cloud of smoke emanating from that cellar. Monica's brother Emory and Mr. Tasker try desperately to break the cellar door open, but before they can get in, the screams rise to a blood-curdling crescendo and then stop. The owner of that voice was Leroy, who has, quite simply, burned to death.

Christine now suffers a nervous breakdown and starts to babble about being blind, and finally screams at Rhoda to stop playing that piano tune over and over. When Rhoda does come out of the room, Monica has to restrain Christine from striking Rhoda. Christine then collapses in tears as she confronts the realization that Rhoda has killed yet another person.

Attempted Murder-Suicide[edit]

That night, she induces Rhoda to confess that very thing, which Rhoda does, all the while insisting that the fault was not hers, but Leroy's, because Leroy shouldn't have scared her with his loose talk about police investigations and evidence. Christine reveals at this point that she has dropped Claude Daigle's medal onto the pilings at the pier where he drowned.

Finally, Christine gives Rhoda what she says are "new vitamins," but are actually sleeping pills, in an amount that is obviously an overdose. After putting Rhoda to bed, Christine shoots herself with Col. Penmark's revolver that they keep in the apartment.

The attempt at murder-suicide is not successful. As further scenes reveal after the fact, the sound of the shot brings Monica and Emory running, and they summon medical aid for Christine and Rhoda. Christine has, unaccountably, missed her brain but has lost much blood; Rhoda has not absorbed a fatal dose of barbiturates and is easily treated by classic gastric gavage ("stomach pumping").

Two days later, Mr. Bravo and Col. Penmark, both returned from their respective cities, discuss the apparent attempt at murder and suicide. Rhoda recovers completely, but Christine must stay in the hospital to recover. Col. Penmark takes Rhoda home, but Richard Bravo asks the hospital doctor whether Christine had mumbled anything while he was attending to her. The doctor remembers that she kept repeating the phrase "bad seed" over and over. Mr. Bravo says that Christine was about to write a book about inherited criminality, but the doctor, as Mr. Bravo had done, totally rejects the theory, saying that no one would dare bear or adopt children if that were the case.

Retribution[edit]

While a thunderstorm is raging outside over the town and surrounding region, Col. Penmark puts Rhoda to bed. Before he leaves her room, Rhoda reveals that Monica has promised to leave Rhoda her pet lovebird if she dies, and that Monica and Rhoda plan to take a sun-bath high on the roof the next day. We may be sure that Rhoda is already planning to collect another treasure, but of course Col. Penmark suspects nothing.

Col. Penmark then waits up. He takes a call from the hospital, as Christine desperately wants to confess to Kenneth that she has "sinned a great sin." The colonel says that whatever the problem is, they will face it together.

Rhoda, meanwhile, has put on her raincoat and sou'wester and gone out of the house, in the storm. She walks all the way to the Fern school grounds, and onto the wharf where Claude died. Rhoda wants, quite simply, to retrieve the medal. Using a flashlight, she spots the medal underwater, and takes an old fishing net (one of several leaning against the wreck of the boathouse at the end of the wharf) to try to snag the medal. Lightning strikes, wrecks the boathouse even further, and knocks Rhoda into the water.

The Casting Call[edit]

The movie, as such, ends here—but then a casting-call sequence appears in which the actors playing the various parts introduce themselves. Rhoda appears next to last, and finally Christine—but then Christine steps toward Rhoda, seizes her, turns her over her knee, and gives her a sound spanking. The last frame is a plea to the audience not to reveal the "startling climax."

Cast[edit]

- Nancy Kelly as Christine Bravo Penmark, aka Ingold Denker

- Patty McCormack as Rhoda Penmark, her daughter

- Paul Fix as Richard Bravo, her father—or so she supposes

- William Hopper as Colonel Kenneth Penmark, USAF, her husband

- Evelyn Varden as Monica Wages Breedlove, the Penmarks' landlady

- Jesse White as Emory Wages, Monica's brother

- Henry Jones as Leroy Jessup, the janitor

- Eileen Heckart as Hortense Daigle, the mother of a boy who dies at Rhoda's hand.

- Frank Cady as Henry Daigle, her husband and the boy's father

- Gage Clarke as Reginald Tasker, a crime historian and houseguest of Mrs. Breedlove and Mr. Wages

- Joan Croydon as Claudia Fern, headmistress of the Fern School

Spoilers end here.

Themes[edit]

The Nature-Nurture Controversy[edit]

The primary theme of the novel, play and film is the Nature-Nurture Controversy regarding the origins of criminal behavior. At issue: Does a habitual criminal inherit a tendency to criminality from his parents or other ancestors, or does criminal behavior result entirely from an unfavorable child-rearing environment?

In the era in which this film was made and released, juvenile delinquency began to be far more prevalent, or far more widely reported and documented, than had been the case earlier in history. The nature-nurture controversy was an attempt at an explanation. Proponents of the "nature" side suggested that some people are born evil—with the clear implication that most people are not born evil. (Reginald Tasker even suggests that those persons "born evil" are "born with a brain that might have been normal thirty-five thousand years ago"—in other words, that they are atavisms, or literally, "throwbacks.") Proponents of the "nurture" side suggest that criminals learn their behavior from other criminals, or make the decision to turn to crime if chronically impoverished or otherwise "disadvantaged."

In point of fact, neither theory is correct. All persons are born with an inherent tendency to evil. The Israelite King David made this point first:Paul of Tarsus quotes this and elaborates further:The fool has said in his heart, "There is no God."/They are corrupt, they have committed abominable deeds;/There is no one who does good./The LORD has looked down from heaven upon the sons of men/To see if there are any who understand,/Who seek after God./They have all turned aside, together they have become corrupt;/There is no one who does good, not even one. Psalms 14:1-3 (NASB)

And yet, the environment, other than the family environment, is not a sufficient reason why some become criminals and others do not. As the terminal "casting call" sequence ironically demonstrates, the key distinction between a child who turns criminal (even as a child) and a child who does not, is discipline. Indeed, the Bible has something to say about this, too, in the words of King Solomon:as it is written,/"THERE IS NONE RIGHTEOUS, NOT EVEN ONE;/THERE IS NONE WHO UNDERSTANDS,/THERE IS NONE WHO SEEKS FOR GOD;/ALL HAVE TURNED ASIDE, TOGETHER THEY HAVE BECOME USELESS;/THERE IS NONE WHO DOES GOOD,/THERE IS NOT EVEN ONE." Romans 3:10-12 (NASB)

He who withholds his rod hates his son,/But he who loves him disciplines him diligently. Proverbs 13:24 (NASB)

For "son," read "child," which can include a daughter, too.

The facts surrounding the Penmark household are damning, but not for the reasons that the panic-stricken Christine Penmark supposes. Rhoda Penmark is not a criminal merely because Bessie Denker, her actual maternal grandmother, was a psychotic serial murderess who killed Christine's brother and tried to kill Christine before making herself an international fugitive. Rather, the fault for Rhoda's criminal tendencies lies entirely with Col. and Mrs. Penmark, by reason of their failures to impose discipline, not by reason of their respective genetic heritages. Col. Kenneth Penmark is a classic absentee father, who thinks he can retain his daughter's affections by buying presents for her and shipping them from the venue of his far-off assignment. Furthermore, he and his wife both have had a habit of overlooking their daughter's sense of overweaning entitlement, lack of a sense of sportsmanship and fair play, and the general attitude of a sore loser. Neither parent wants to believe anything ill of their daughter, and Rhoda has become adroit at fostering their unfounded belief in her as a "perfect little girl," through flattery and an outward show of manners that looks perfectly correct in every detail but in fact is entirely hypocritical and therefore without meaning. Indeed, Christine Penmark knows that her daughter is "an adroit liar," and has never taken the proper steps to correct her daughter for that behavior alone.

Child crime[edit]

The spectacle of an eight-year-old girl murdering a schoolmate and then murdering an adult witness seemed far-fetched in the era of the film's release. Sadly, that spectacle has been repeated today, and distressingly often, and in a manner that might have shocked even Mr. March, the author of the original novel.

Aside from the (at the time) extreme youth of a character depicted as having committed so violent offense as murder, youth crime had become epidemic at the time. But the general percept was that this was a phenomenon largely confined to America's largest cities. This story takes place in a small town whose residents are remarkably well-off. Any story must depict an unusual situation in order to be dramatically effective, but William March's larger point is that no neighborhood or town is immune from such a curse, and further, that a near-perfect surface moral manner can and often does hide a criminal attitude of even the most appalling nature.

Bullying[edit]

The phenomenon of child bullying is perhaps the second most central phenomenon in this story. For example, Hortense Daigle reveals that she was the victim of such bullying as a child, on account of her name. She observes that children can be quite cruel to one another, which is why she is the first to suspect that her dead son died after having become a target of bullying by Rhoda Penmark.

In fact, Rhoda Penmark illustrates the bullying phenomenon from two different perspectives. She bullies Claude Daigle and ultimately kills him after he shows himself a better student than she in an area of student achievement. Subsequently, she becomes the target, though by no means a victim, of bullying from another, unlikely quarter: specifically, from a janitor who has the mind and emotions of an eight-year-old and thinks that he can "take her down a peg" by taunting her with visions of police investigations, a trial, and ultimately capital punishment. Of course, the United States did not subject any of its children to capital punishment at the time, but that does not stop Leroy, the janitor, from trying to fill a child's mind with visions of color-coded electric chairs for boys and girls convicted of murder. That Leroy would do such a thing is because he is not behaving as an adult, but rather as a child.

The ultimate irony is that Leroy has targeted someone who not only knows how to fight back, but who fights back for keeps. Tragically, his mind is incapable of the simple chain of adult logic that would inform him that, were she actually guilty of murder, she would not cower in fear of his accusations when they happened to strike close to home. To the contrary, she would kill him as easily as she killed Claude Daigle. Leroy, with his child mind, fails to process this logic. Result: murder.

Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry[edit]

The practices of clinical psychology and psychiatry receive very harsh treatment in at least two respects. First, Monica Breedlove is a type of every "busy-bodied" adult who:

- Dabbles in psychiatry with no appreciation for the discipline's actual strengths and weaknesses, and

- As part of said dabbling, compromises the discipline of a child who is not her own.

Though Christine Penmark's failings as a child-rearer are evident and considerable, Monica Breedlove compounds the problem by lavishing presents on Rhoda and thinking to "make up" for Rhoda's disappointment. Worse yet, Monica takes note of Rhoda's tendencies toward grasping and hoarding and actually praises them as "natural" and somehow more "real." Leroy Jessup, though one can scarcely credit him as a judge of character, nevertheless describes Monica very aptly as a "know-it-all" who thinks that no one knows as much about human nature as does she.

More to the point, Monica's fascination with abnormal human behavior approaches the level of an unhealthy obsession. The richest irony is that Monica Breedlove, having subjected herself to psychoanalysis, now believes herself qualified to judge the state of disturbance or adjustment in everyone to whom she is at all close. Her activities as an amateur psychiatrist become frankly dangerous when she obtains a supply of barbiturates and gives them to Christine Penmark, who then uses them in an attempt to kill Rhoda to spare her the ignominy of a public trial and sentencing. But the other members of her "psychiatry club" are little better, obsessed as they appear to be with classic cases of serial murder and similar criminality, an obsession that appears to be an extreme example of the phenomenon of "rubbernecking" that one observes (usually to great annoyance) at the scene of any motor-vehicle accident.

But William March's criticisms of psychiatry are by no means limited to the attempt by amateurs to practice it. Professional psychiatrists like Reginald Tasker, and crime journalists like Richard Bravo, also have earned Mr. March's contempt. In March's view, even the professionals, steeped as they are in their pet theories of the origins of undesirable or antisocial behavior, are utterly at a loss to treat a real case of criminality that is quite literally under their noses.

Social class[edit]

The story draws a deliberate contrast among at least three social classes to which various characters belong:

- The affluent class, represented mainly by the Penmarks and, to a lesser extent, by Claudia Fern and her sisters.

- The middle class, represented by the Daigles.

- The lower class, represented by Leroy Jessop.

Class tension pervades the script on several levels. Rhoda Penmark gives no indication of ever having learned the maxim noblesse oblige (literally, "nobility obliges"), and Christine Penmark gives every indication of being utterly ineffectual in imparting any such lesson. Leroy Jessop is a type of the member of the lowest class, who notices that a member of the highest class is not behaving in a "noble" manner at all, and is determined to attack that person (not realizing that his target can strike back with lethal force). Hortense Daigle seeks to vindicate herself by blowing the lid off what she sees as scandalous behavior by certain persons, who have always looked down on her on account of her lack of station, who have either wronged her (like Rhoda, though she doesn't fully realize that until much later) or are trying to "cover up" to avoid embarrassment (like Claudia Fern).

The class distinctions are also important in explaining Christine Penmark's longstanding blindness to her daughter's bad behavior. Christine convinces herself that criminals are made in the environment of a social class to which she, of course, does not belong, because she is somehow above such classes. What throws her into panic mode is realizing that she is descended from a very dangerous killer who always escaped punishment by fleeing from one jurisdiction to another, and it is that fact that frightens her by making her realize that crime respects no class distinctions. Little does she (or indeed anyone else) realize that crime does not respect genetic heritage, either.

Alteration of the ending[edit]

In the original stage play, Christine Penmark's self-inflicted wound proves fatal, and Rhoda does not attempt that foolhardy search for the stolen medal in the middle of a thunderstorm, but lives, presumably to kill again if sufficiently (by her lights) provoked.

The Motion Picture Production Code demanded that any person who killed another receive punishment for that death before the end credits rolled. The usual interpretation of that is that the malefactor must suffer the punishment in relatively short order, and not years later.

In point of fact, very few criminals know to "quit while they are ahead." Thus, had Rhoda Penmark been a real person, she probably would have continued to commit crime after crime, until at length she would commit a crime that she could not conceal, and fall into the hands of an authority that would not make a botched attempt at summary justice aimed at sparing her any embarrassment or any such thing as what Christine Penmark attempts. Instead, that authority would see to it that Rhoda paid for her latest mistake, and in full. This might have happened many years later, but that she would successfully elude prosecution to the very end seems unlikely. So Mr. LeRoy might have achieved his objective (to show that crime never pays forever) by framing his story, not at a pier in a thunderstorm that rages immediately after the failed murder-suicide, but instead in a courtroom where an adult Rhoda Penmark is awaiting jury deliberation after having stood trial for a murder that she committed as an adult. Following the wrapup of the story of Rhoda as a child, the adult Rhoda would have stood to receive the verdict in her adult case; that verdict would, of course, have been "Guilty" and the purpose of the Code would have been served.

Furthermore, one could argue that Mervyn LeRoy ultimately did fail to observe the Code in every particular, and that the Production Code Administration failed to catch one key lapse: that Rhoda Penmark's biological grandmother, Bessie Denker, did escape punishment by moving from one jurisdiction to another and never being subject to extradition. That she never appeared on camera would seem to be almost a specious excuse, and perhaps this case was one of many, even before Psycho (1960), that strained the Code to the breaking point.

However, the criticism of Mr. LeRoy for adding the "casting call" sequence at the end seems misplaced. Legend has it that Mr. LeRoy included that sequence in order to settle the nerves of his audience, at a time when such consideration might have been much appreciated. Furthermore, the spanking scene illustrates the most important point to be made: that had Christine Penmark taken her daughter in hand and corrected her behavior long before, none of the horrific events depicted in the film (and the stage play) need ever have happened at all. One must observe, however, that Col. Penmark's negligence as a father receives scant attention in that sequence.

Awards and Nominations[edit]

Nancy Kelly, Patty McCormack, and Eileen Heckart, who had performed their respective roles in the Broadway production of the stage play, all received nominations for the Academy Award for their performances, Kelly for "Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role," and McCormack and Heckart for "Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role." In addition, Harold Rosson received a nomination for "Best Cinematography."

Miss McCormack and Miss Heckart were both nominated for Golden Globe awards for "best supporting actress"; Miss Heckart actually won that award.

Categories: [English-language films]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/05/2023 08:24:52 | 6 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/The_Bad_Seed | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF