Deism

From Nwe

From Nwe

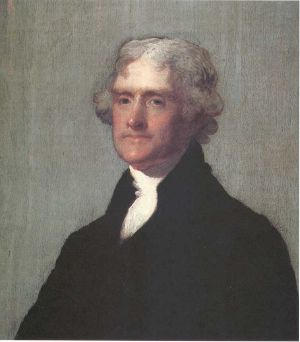

Deism (from Latin: deus = God) refers to the eighteenth-century movement in modern Christianity which taught that reason—rather than revelation—should form the basis of religion. In England and the American colonies, this movement promoted the idea that there were natural principles which could be agreed upon by all people regardless of the positive (historical) differences among their many faiths. Many of the American founding fathers, among them Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, identified with Deism, and their outlook helped to create the "American civil religion" that embraces people of all creeds.

In France, on the other hand, Deism in the person of Voltaire took an anti-Christian stance, opposing the "religion of reason" against all revealed religions and their churches. This continental brand of Deism crystallized the resentment of Europeans against the bloody wars of religion that had ravaged Europe during the previous century by proclaiming a new faith that denied all the particularistic dogmas over which these wars were fought.

Secondarily, Deism has come to denote the theological belief that God created the universe according to scientific laws, but does not interfere in its daily operation. Voltaire first articulated this argument in his Traité de Métaphysique (1734). God is like a watchmaker who designed the universe and set it in motion. He does not interfere with its operation (especially through historical figures like Jesus or churches), yet his presence is still visible in the grain of all creation.

Most Anglo-American Deists did not have such a minimalistic view of God's activity in the world; thus Lord Herbert of Cherbury, considered to be the father of English Deism, took as one of his five "innate principles" compatible with reason that there are rewards and punishments after death, and in general the American Deists believed in a general concept of divine providence. Nevertheless, by not allowing special revelation, these Deists were left with a weak theological foundation that could not clearly explain God's activity in the world. Hence, today it is Voltaire's more extreme view that defines the Deist position philosophically. All Deists dismiss the role of miracles that cannot be explained by reason and downplay emotion as a stimulant for faith.

Deism as Philosophy

Deism offers a philosophical perspective concerning the nature of God and the cosmos. It posits the belief in a creator God, the first cause who brought the universe into existence. According to the argument from design, God is like the watchmaker (or the “Primordial Architect,” in Sir Isaac Newton's terms) and much as the watchmaker fashions the parts and functions of the watch, God similarly put into place the machinations of the universe, and provides the energy which sets the universe in motion. However, while Deists claim that God is the source of all motion and matter, they also believe that God's intercession into his creation only occurs occasionally, if at all.

The watchmaker hypothesis is not specifically incompatible with the scientific theory of evolution. For example, evolution through natural selection might be a process designed by God in order to carry through the unfolding of creation, although it is not compatible with the dogmatic idea held by some evolutionists who argue the universe was self-created randomly out of chaos. Those Deists that hold God directly intervenes occasionally to repair or improve the "watch," for example by creating a new species, would not be compatible with the theory of evolution, which holds that new species can arise on the basis of natural selection.

In the sphere of morality, Deists conceive of God as the supreme authority of the moral world. Many Deists say that just as God provided the laws governing the physical universe, God also set in place the moral order. In this way, he serves as the judge of all moral beings within the cosmos, but he does not necessarily become involved in the enforcement of the law. Instead, humans are punished and rewarded as a function of their own observance of the natural moral laws. Consequently, Deism places emphasis on the requirement of a virtuous life amidst the freedom of human choices. Disobedience to God's laws will naturally result in negative consequences for the moral being, thus God's personal intervention is not required. It is human reason that replaces a personal relationship with God, since "salvation" in the Deist philosophy is assured for those who live a moral life based upon knowledge of the laws created by God, including what constitutes good and what constitutes evil.

History of Deism

Beginnings

Deistic ideas have existed since antiquity, and can be identified in the works of pre-Socratic philosophers (such as Heraclitus). However, it was not until the time of the European Enlightenment—with its emphasis on rigorous skepticism, deductive logic, and empiricism—that deism came into its own as a subject of philosophical discourse. The foundations of the deist movement were laid by Edward Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648), who asserted that human reason was sufficient for purposes of attaining certainty with regard to fundamental religious truths. He also insisted that religion should be deeply involved in practical duties. Deistic writers that followed Herbert enlarged these themes, particularly the postulation that natural reason should be the basis of religion.

The independent works of other seventeenth-century figures also had a hand in affecting the rise of Deism. Although Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was generally opposed to the concept of natural religion, the philosophical concepts he espoused championed rational thought against ecclesiastical authority. Furthermore, the Cambridge Platonists, reacting to the increased influence of anti-rationalist dogmatism among the Puritan divines, put forward what they conceived to be a set of rational grounds for Christianity. They used Platonism to argue for human reason as the paramount receptacle for divine revelation.

Like Hobbes, John Locke (1632-1704) had an unintentional effect on deistic thought. In his work The Reasonableness of Christianity, he delineated the progression of Christian doctrine through history discriminating between the valuable and worthless elements of the Creed, and showing particular skepticism toward elements of the Biblical texts which involve miracles and revelation; further, he conceived the Christian religion to be a powerful moral philosophy rather than a means to invigorate the human will with spirit. Although each of these ideas had been formulated prior to Locke's publication, this was the first instance where they were combined systematically. Locke arrived at the conclusion that religion in the form that it currently existed was in need of extensive modification. Hence, the foundations for the Deist movement had been laid.

Newtonian physics, the intellectual basis for the scientism of the Enlightenment, propagated the idea that matter behaves in a mathematically predictable manner that can be understood by postulating and identifying laws of nature. Concepts borrowed from the observational methods of science such as objectivity, natural equality, and the prescription to treat like cases similarly became the rubric for scrutinizing all domains of life, and, inevitably, these principles came to inform the reinterpretation of religion, as well. Finally, exasperation as a result of the immense toll centuries of religious warfare had taken upon Europe provided a powerful impetus for placing a more rational framework upon spiritual matters.

Deism in England

The height of deist popularity occurred in England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Deism furthered the British people's desire to end the warfare that for over a century had pitted Catholics against Protestants, Anglicans against Puritans, by establishing as common ground a set of universal principles of religion to which all people could subscribe. Thus Lord Herbert's list:

- That God exists

- That God ought to be worshipped

- That the practice of virtue is the chief part of the worship of God

- That men have always had an abhorrence of crime and are under the obligation to repent of their sins

- That there will be rewards and punishments after death.[1]

Herbert believed that a natural relation based upon such principles and shared by all people would lead to religious harmony, or at least toleration, rather than the conflict and strife brought about by the differing historical doctrines of the established churches. The idea of a common platform for all people of faith (or at least all Protestants) would eliminate the persecutions, the burnings at the stake, and the excommunications that had riven England and create a basis for national unity.

The later group of deists were a close-knit circle of free thinkers. They were a well educated and well connected group. As well as being theologically radical some were also critics of monarchy and advocates of republicanism. Their numerous pamphlets and books stirred up a huge debate in England which drew in many of the best known philosophers, scientists and churchmen.

John Toland (1670-1722) wrote the first explicitly deistic work, Christianity Not Mysterious (1696). Drawing upon some of Locke's postulations, he stressed a process whereby truth was inferred from nature rather than revelations directly from the divine. Anything a reader of the scriptures could not comprehend through common sense was to be considered false. Toland meticulously studied the Gospels and clarified every part of them which seemed contrary to reason. Reason, he asserted, was to be the primary yardstick in all matters religious.

The publication of Toland's ideas caused much uproar throughout Britain. The Irish parliament ordered mass burning of the book, while English ecclesiastical authorities declared it essentially anti-Christian in its denial of miracles. Toland had started the process of undermining the credibility of the Christian Bible as a whole, suggesting that it was full of superstition and should be reconsidered. After Christianity Not Mysterious, Toland's views grew – bit by bit – more radical. His opposition to hierarchy in the church also led to opposition to hierarchy in the state; bishops and kings, in other words, were as bad as each other, and monarchy had no God-given sanction as a form of government. In politics his most radical proposition was that liberty was a defining characteristic of what it means to be human. Political institutions should be designed to guarantee freedom, not simply to establish order. For Toland, reason and tolerance were the twin pillars of the good society. This was Whiggism at its most intellectually refined, the very antithesis of the Tory belief in sacred authority in both church and state. Toland's belief in the need for perfect equality among free-born citizens was extended to the Jewish community, tolerated, but still outsiders in early eighteenth century England. In his 1714 Reasons for Naturalising the Jews he was the first to advocate full citizenship and equal rights for Jewish people.

Anthony Collins (1676-1729) was a wealthy free-thinker and friend of John Locke. In a published exchange of letters with Samuel Clarke he rejected the idea of a soul and developed the idea that consciousness was an emergent property of the brain. As a materialist he also argued for determinism. In 1713 he published Discourse of Freethinking occasioned by the Rise and Growth of a sect Called Freethinkers. Here Collins went beyond Toland in championing rational inquiry. According to Collins, all the great moral figures in the Bible taught their disciples by appealing to reason, rather than fear. In contrast, he argued the church had cultivated fear through superstitious beliefs in order to inspire humans to behave morally, and in the process had created what Collins viewed to be moral corruption. His prescription for religious reform was to excise such fear-inducing superstitions from religious teaching, and to concentrate on the development of morality through rationality in each individual.

In a later work, Discourse of the Grounds and Reason of Christian Religion, Collins turned the focus to the consideration of whether or not prophecy and miracle are credible phenomena. Specifically, this debate centered around an idea which had been widely accepted up until that time: the notion that the correspondence of Old Testament prophesy and New Testament events were adequate proof of Christianity's truth. Collins challenged this, as he questioned the authenticity and accuracy of events such as those in the Gospels which were supposedly dictated by New Testament writers such as the Apostles. If the miracles reported by these authors were to remain in religious discourse, Collins suggested they be reinterpreted as allegory or metaphor to supplement the more reasonable contributions of Christ and other religious figures. Collins perpetuated suspicions toward the veracity of Biblical documents, and provided further momentum for Biblical criticism.

In 1730 Matthew Tindal (1657-1733) published Christianity as Old as the Creator, a book that marked what was probably the culmination of all deist thought. Tindal synthesized the various deist arguments together and presented them in more intelligible language than his predecessors. He repudiated the mysterious aspects of religion and promoted a general distrust toward religious authority. The ultimate value of religion, he contended, was to aid humans in fashioning their own personal beliefs and to cultivate their moral nature, rather than encouraging them to depend on revelation. He held that in the context of their moral faculties, all humans were equal in the eyes of God at all times. Further, through the gift of reason, humans held the ability to comprehend the consequences of their actions without the continual assistance of God. For Tindal, human duties are evident through the reason behind things and their relationships with one another. Religion, in Tindal's view, was seen as what naturally arises from consideration of God. It was from such natural reflections that religious edifices were constructed. Tindal held that placing anything in religion that is not demonstrable by reason to be an insult to the faculties of human beings and ultimately a defamation of the honor of God.

Tindal's work provoked about one hundred and fifty responses, among them Case of Reason (1732) published by the mystic and Anglican divine William Law (1686–1761) which aimed to show the limits to reason.

Deism in France

Even though it had been discredited in England, Deism was welcomed in other countries. French Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau found the ideas particularly appealing and introduced some new elements of their own. Voltaire used Deism as a vehicle for expressing resentment against the social repression perpetuated by the Roman Catholic Church in France. Of course, the internal passions of the French were already at a peak due to the impending revolution, and deism fed upon this, becoming identified with the broader anti-ecclesiastical movement. Rather than transforming the theology of the church as the English deists had hoped to do, the French advocated an eschewal of theology altogether. This was partly because the Catholic Church in France was unable to respond to the deist challenge in the way that Christians in England had. In place of the Roman Catholic Church, they suggested a non-dogmatic religion with Deist ideals. This attempt eventually failed, as the French variation of Deism gradually evolved into a form of materialism devoid of any large-scale religiosity. Rousseau made similar attempts to instill Deism into French life, but also had little success.

Deism in eighteenth-century America

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the newly developing land of America was dominated by Protestant Christianity, and the popularity of Deist thought, which was by this time subsiding in England, was on the ascendancy in American soil. In 1790 Elihu Palmer, a one-time Baptist minister, launched a nationwide crusade for Deism. By the turn of the century, Deism had grown in popularity and started to become more accepted among mainstream America. This caused a vociferous backlash from the Christian establishment, but Deism continued to flourish in America well into the nineteenth century.

Since America was founded when Deism was popular, it is not surprising that numerous founding fathers of the nation such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington identified with some of its ideas. In fact, the first six presidents of the United States, as well as four later ones, had deistic beliefs. Jefferson attempted to produce his own variation of Biblical scripture with the publication of the so-called "Jefferson Bible," also known as The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. Jefferson composed this volume by removing sections of the New Testament containing supernatural aspects. Also, he excised portions which he interpreted to be misrepresentations or additions that had been made by the writers of the Gospels. What was left, supposedly, was a completely reasonable version of the doctrine of Jesus, featuring only those parts believable to rational people.

Decline in popularity

Numerous factors contributed to a general decline in Deism's popularity. In England, Christian opponents of Deism included Bishop Joseph Butler (1692-1752) who wrote, The Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed, to the Course and Constitution of Nature, which accepted reason but showed its limitations and the imperfect character of knowledge. It was also challenged by the empiricism of Bishop Berkeley (1685–1753). Most notably, the writings of David Hume increased doubt about the sturdiness of the First Cause argument and the argument from design. In formulating his critique of Deism, Hume targeted its fundamental assumption that religion is based on natural principles of creation and therefore religion has been complete from the time of creation itself. Conversely, Hume argued that early religion would likely have been barbarous and inchoate—and only through the use of reason would these early absurdities progressively be done away with. Hume had the benefit of modern scholarship and used evidence of new anthropological findings to support his views of earlier religion.

Meanwhile, English Christianity was reinvigorated by the revival led by John Wesley (1703-1791), who accepted that faith should be reasonable but also appealed to experience—specifically a personal encounter with Christ. Several Christian Great Awakenings in America emphasized the accuracy of the Bible, advocated a more personal relationship with Christ, an active presence of God in the world, and argued that prayer could alter events. Moreover, the rise of Unitarianism converted many Deist sympathizers. This could be expected, as the Unitarians adopted many of the Deist ideas.

Furthermore, pointedly anti-Deist and anti-reason campaigns were organized by some Christian clergymen to vilify Deism and equate it with atheism in public opinion. Such developments reflected a general realization in the nineteenth century that reason and rationalism could not solve all of humanity's problems. As emotion became an important component of life again in the age of Romanticism, Deist ideals subsided.

However, the Deists provided a very useful spur to orthodox Christians who took on board the Deist critique and refined and improved their philosophical and theological arguments. It also provided a stimulus to Biblical scholarship and archeology as apologists sought other evidence to support the Biblical narrative. In England and America where extreme Deism was discredited and Christianity remained intellectually respectable, subsequent movements for social change were led mainly by Christians.

Contemporary status

Newtonian physics, when simplified, is considered deterministic. Over the past several decades it has been largely superseded by newer theories in physics, most notably quantum mechanics, which has been commonly interpreted as non-deterministic. Since Deism is so deeply rooted in the Newtonian mode of thinking, any further philosophical development has been greatly impeded by these philosophical shifts in modern science. Some modern revivals of Deism such as pantheism and panentheism have been spurred in limited numbers, usually relying on the internet for recruiting members and rarely becoming reified as corporate religious communities. However, some Unitarian Universalists are currently resurrecting Deist ideals in order to counter the rise in popularity of Christian Fundamentalism.

Contributions of Deism

Despite its significant decline in popularity, Deism still holds an important place in religious history as both a philosophy and an historical movement. It spurred great scientific advances and much invention by people like Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz. Few movements in history gave reason and rationality such importance in religion as the Deists did. Deists made religious scripture and doctrine fair game for literary criticism and scientific analysis. Furthermore, Deists made it evident that while God is important, so too is the human being who conceives of God. Deism combined the common sense of humans with the trained skill of intellectuals so as not to lose the virtues of humanity in relationship with God. This was particularly helpful in the times of great technological advancement contemporaneous with the Deist movement. Conversely, by concentrating so heavily on intellectualism and reason, Deists also made evident the importance of emotion as a stimulant for faith. Later religious systems, such as the Wesleyan movement, were no doubt conscious of the rise and decline of Deism in their attempts to balance reason and faith in their own beliefs. Deism's continuing legacy in America, which was founded in part on Deist principles of religious toleration and a belief in "self-evident truths," to paraphrase the Declaration of Independence, has fostered a public culture where faith and religiosity are important to people beyond the teachings of any particular denomination.

See also

- Cosmological argument

- Cosmotheism

- Evolutionary Creationism

- Free thought

- Ignosticism

- Panentheism

- Pantheism

- Philosophical theism

- Polydeism

- Transcendentalism

- Transtheism

Notes

- ↑ James C. Livingston. Modern Christian Thought. (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 14.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Collins, Anthony. A Discourse of the Grounds and Reasons of the Christian Religion. New York: Garland Publishing, 1976. ISBN 0824017668

- Joyce, Gilbert Cunningham. “Deism.” Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics, James Hastings, ed., 334-345. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1910.

- Livingston, James C. Modern Christian Thought. New York: Macmillan, 1971.

- Tindal, Matthew. Christianity as Old as the Creation. reprint ed. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2005 (original 1728). ISBN 1417947276

- Toland, John. John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious: Text, Associated Works and Critical Essays, edited by Alan Harrison, Richard Kearney, Philip McGuinness. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1998 (original 1702). ISBN 187467597X

- Walters, Kerry S. Rational Infidels: The American Deists. Durango, CAL: Longwood Academic, 1992.

- Wood, Allen W. "Deism." Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mercia Eliade. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1987.

External links

All links retrieved July 26, 2022.

- DEISM: The Union of Reason and Spirituality

- English Deism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- French Deism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- religious tolerance.org article on deism Deism: About the God who went away.

- World Union of Deists

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 19:49:51 | 120 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Deist | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF