Works Progress Administration

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia The Works Progress Administration (later Work Projects Administration, abbreviated WPA), was created on May 6, 1935 by Presidential order (Congress funded it annually but did not create a permanent agency.). It was the largest and most comprehensive New Deal agency, employing millions of people and affecting every locality. The WPA refused to allow any job training (which labor unions strongly opposed),[1] with the result that WPA experience did not lead to better job opportunities. It did reduce unemployment by finding jobs for the least employable and most needy men and women—both black and white—in the country.

WPA continued and extended the FERA relief programs started by Herbert Hoover and continued under Franklin D. Roosevelt. Unlike FERA (which funded state and local programs), the WPA was run directly by the federal government.

Headed by Harry Hopkins, the WPA provided jobs and income to millions of unemployed during the Great Depression. It built many public buildings and roads, and as well operated a large arts project. Until it was closed down by Congress in 1943, it was the largest employer in the country — indeed, the largest employer in most states. Only unemployed people on relief were eligible for most of its jobs. The hourly wages were the prevailing wages in the area, but workers could not work more than 30 hours a week. Before 1940, there was no training involved to teach people new skills. Unskilled workers were very happy to have a real job and a real paycheck rather than waiting in line for food baskets. However skilled workers who found themselves on the WPA were embarrassed by the downskilled jobs and tried to hide their status. Thus actors did not want their names to appear on programs for WPA theater productions, fearing they would be stigmatized as poor actors.After the program died it was seldom referenced in politics, either pro or con. Some liberals often had a fond memory of the WPA and therefore an effort was made to set up a jobs program under President Jimmy Carter in the late 1970s, but by then unskilled manual laborers made up too small a proportion of the work force to make a difference.

Contents

Overview[edit]

Types of Projects[edit]

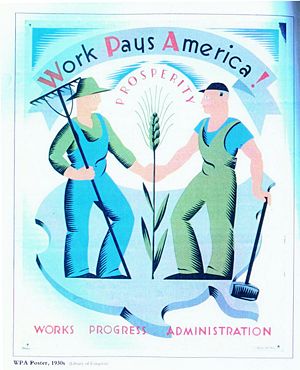

About 75 percent of employment and 75 percent of WPA expenditures went to public facilities such as highways, streets, public buildings, airports, utilities, small dams, sewers, parks, libraries, and recreational fields. The WPA built 650,000 miles of roads, 78,000 bridges, 125,000 buildings, and 700 miles of airport runways. Seven percent of the budget was allocated to arts projects, presenting 225,000 concerts to audiences totaling 150 million, and producing almost 475,000 artworks.[2]

Though some 90% of WPA projects were directed at unskilled blue-collar workers, it also took in many unemployed white-collar artists, musicians, actors, doctors, and writers in such projects as the Federal Theater Project and the Federal Writers' Project.

For a more detailed treatment, see New Deal.

Over 8,500,000 Americans were hired through the WPA mostly to work in manual labor, building roads and making parks. Unemployed artists and writers were given work through a branch of the WPA known as the Federal Writers’ Project. Among the most compelling products of the Writers' Project are the interviews with former slaves.[3] A sampling of projects includes:

Worker Profile[edit]

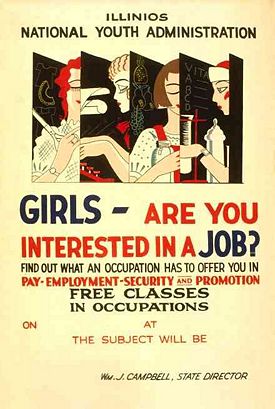

The target recipients were household heads on relief (about 15% of whom were women). Youth programs were operated separately by the National Youth Administration, or NYA. The average worker was about 40 years old (about the same as the average family head on relief).

The WPA reflected the strongly-held belief at the time that husbands and wives should not both be working (because they would take one job away from a breadwinner.) A study of 2,000 women workers in Philadelphia showed that 90% were married, but wives were reported as living with their husbands in only 15 percent of the cases. Only 2 percent of the husbands had private employment. "All of these [2,000] women," it was reported, "were responsible for from one to five additional people in the household." In rural Missouri 60% of the WPA-employed women were without husbands (12% were single; 25% widowed; and 23% divorced, separated or deserted.) Thus only 40% were married and living with their husbands, but 59% of the husbands were permanently disabled, 17% were temporarily disabled, 13% were too old to work, and the remaining 10% were either unemployed or handicapped. An average five years had elapsed since the husband's last employment at his regular occupation. [Howard 283] Most of the women worked in sewing projects, where they were taught to use sewing machines and made clothing, bedding and supplies for hospitals and orphanage.

Relief for Blacks[edit]

The share of FERA and WPA benefits going to blacks exceeded their proportion of the general population. The FERA's first relief census reported that more than two million black Americans were on relief in early 1933, a fraction of the black population (17.8%) that was nearly double the proportion of whites on relief (9.5%). By 1935, there were 3,500,000 blacks (men, women and children) on relief, almost 30 percent of the black population; plus another 200,000 black adults were working on WPA projects. Altogether in 1935, about 40 percent of the nation's black families were either on relief or were employed by the WPA.[4]

Civil rights leaders initially complained that black Americans were proportionally underrepresented. African-American leaders made such a claim with respect to WPA hires in New Jersey: "In spite of the fact that Negroes indubitably constitute more than 20 per cent of the State's unemployed, they composed 15.9 per cent of those assigned to W.P.A. jobs during 1937."[5] Nationwide in late 1937, 15.2% were African American. The Urban League magazine Opportunity hailed the WPA:[6]

It is to the eternal credit of the administrative officers of the WPA that discrimination on various projects because of race has been kept to a minimum and that in almost every community Negroes have been given a chance to participate in the work program. In the South, as might have been expected, this participation has been limited, and differential wages on the basis of race have been more or less effectively established; but in the northern communities, particularly in the urban centers, the Negro has been afforded his first real opportunity for employment in white-collar occupations.

Employment[edit]

The goal of the WPA was to employ most of the unemployed people on relief until the economy recovered. Harry Hopkins testified to Congress in January 1935 why he set the number at 3.5 million, using FERA data. At $1200 per worker per year he asked for and received $4 billion.

"On January 1 there were 20 million persons on relief in the United States. Of these, 8.3 million were children under sixteen years of age; 3.8 million were persons who, though between the ages of sixteen and sixty-five were not working nor seeking work. These included housewives, students in school, and incapacitated persons. Another 750,000 were persons sixty- five years of age or over. Thus, of the total of 20 million persons then receiving relief, 12.85 million were not considered eligible for employment. This left a total of 7.15 million presumably employable persons between the ages of sixteen and sixty-five inclusive. Of these, however, 1.65 million were said to be farm operators or persons who had some non-relief employment, while another 350,000 were, despite the fact that they were already employed or seeking work, considered incapacitated. Deducting this two million from the total of 7.15 million, there remained 5.15 million persons sixteen to sixty-five years of age, unemployed, looking for work, and able to work. Because of the assumption that only one worker per family would be permitted to work under the proposed program, this total of 5.15 million was further reduced by 1.6 million--the estimated number of workers who were members of families which included two or more employable persons. Thus, there remained a net total of 3.55 million workers in as many households for whom jobs were to be provided." [7]

The WPA employed a maximum of 3.3 million in November 1938. Worker pay was based on three factors: the region of the country, the degree of urbanization and the individual's skill. It varied from $19/month to $94/month. The goal was to pay the local prevailing wage, but to limit a person to 30 hours or less a week of work.

Total expenditures on WPA projects through June, 1941, were approximately $11.4 billion. Over $4 billion was spent on highway, road, and street projects; more than $1 billion

on public buildings; more than $1 billion on publicly owned or

operated utilities; and another $1 billion on welfare projects including sewing projects for women, the distribution

of surplus commodities and school lunch projects. [Howard 129]

Cultural Programs[edit]

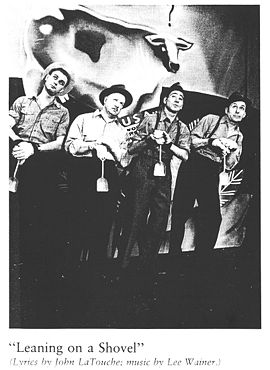

About 10% of the WPA went for cultural programs to support unemployed white collar workers, writers, artists, actors and musicians in four major programs, the Music Project, the Writer's Project, the Arts Project, and the Theatre Project - While providing cultural stimulation, the WPA also had drawbacks. Oftentimes mediocrity was perpetuated by using persons of limited talent; likewise, political rather than aesthetic criterion for judging success and poor editing (in the case of the Writer's Project) led to stifling of creativity. A harmonious working relationship between the artists and the agency was never adequately established. Further, individuals were often subjected to censorship, used as propaganda, and imposed on by Congressional committees seeking political aggrandizement.[8] The Federal Theatre Project from its establishment in 1935 until its demise in 1939 was directed by Hallie Flanagan. Theatre centers nationwide produced a wide variety of plays independently and simultaneously, including works by Sinclair Lewis, George Bernard Shaw, and Eugene O'Neill. The Federal Theatre Project produced both regional and national projects and struggled against censorship and cuts in funds for four years before it was ended for political reasons. The Federal Writers' Project directed by Henry G. Alsberg, operated in every state to produce an American Guide Book. It undertook a massive collecting process on a county level throughout the country and produced not only a national guide but also one for each state and numerous localities. The Historical Records Survey, directed by Luther H. Evans, employed 3400 unemployed librarians, archivists, teachers and others, who located and inventoried the public records of every state, such as county records on births, marriages, and deaths, church and cemetery records, newspapers, schools, and memorabilia. It also created an index to the federal census of 1900, which was used to authenticate the ages of people who had no birth certificate but were eligible for old age assistance. The Federal Music Project sponsored thousands of concerts across the country. In San Diego the Federal Opera Company made "Cavalleria Rusticana" its first production, with the WPA sewing project making costumes. "Gondoliers" was the second offering and the first to go on the road. By 1937, 73 performances of a variety of shows had been offered to 73,000 people.

NYA[edit]

The National Youth Administration was the WPA's youth division. Work study projects provided jobs for high school and college students. Unlike the CCC it enrolled women. The NYA ran training programs—even alternative high schools run outside the public school system—to provide training in skills that would not compete with labor unions.

Lyndon Johnson was the NYA director in Texas, Aubrey Williams was national director; Mary McLeon Bethune, Director, Division of Negro Affairs . Reporters visited one site in Arkansas:[9]

- "in Russellville, Arkansas, 31 NYA boys... are working on a complete campus for out-of-school, unemployed Arkansas youth. We saw some of these young men building dormitories and a supervisor's house. The plans call for four dormitories to house 96 youth, a recreation hall, a dining hall, athletic grounds, and, adjacent to this campus, a poultry house, barn, and machinery repair shop. The boys may also choose work and related training in auto mechanics, power plant operation, or diversified agriculture. In these four Arkansas Resident Centers that we visited, boys and girls do NYA work 100 hours a month to earn $25 each, of which they pay $18 for board and room and 50 cents into a co-operative medical fund."

Criticism[edit]

The WPA had numerous conservative critics unlike the Civilian Conservation Corps, which was quite popular. One of the principal criticisms was that the program wasted federal dollars on projects that were not always needed or wanted. A relic of this criticism survives today in the form of a satirical observation that WPA workers were hired 'to rake leaves in the park.' White-collar WPA projects in particular were often singled out for their sometimes overtly left-wing social and political themes. One criticism of the allocation of WPA projects and funding was that they were often made for political considerations. Congressional leaders in favor with the Roosevelt administration, or who possessed considerable seniority and political power often helped decide which states and localities received the most funding. The most serious criticism was that Roosevelt was building a nationwide political machine with millions of workers. The Hatch Act of 1939 outlawed political activities on government time.

The WPA's enemies ridiculed the weak work habits it encouraged, by cruel jokes, calling it "We Poke Along," "We Piddle Along" or "We Putter Around." This is a sarcastic reference to WPA projects that sometimes slowed to a crawl, because foremen on a government project devised to maintain employment often had no incentive or ability to influence worker productivity by demotion or termination. This criticism was due in part to the WPA's early practice of basing wages on a "security wage," ensuring workers would be paid even if the project was delayed, improperly constructed, or incomplete.

Evolution and termination[edit]

In 1940 the WPA changed policy and began vocational educational training of the unemployed to make them available for factory jobs. Previously labor unions had vetoed any proposal to provide new skills. Unemployment disappeared with the onset of war production in World War II, so Congress shut down the WPA in late 1943.

Corruption[edit]

Kentucky[edit]

In the 1938 election Senator Alben Barkley was being opposed for the Democratic nomination in the primary in Kentucky by "Happy" Chandler, then governor of the state. During the election grave charges were made in the Scripps-Howard Republican newspapers about the manner in which WPA workers in Kentucky were being forced to support the administration candidate. A special Senate committee investigated the charges.[10]

In the first WPA district of Kentucky, one WPA official went to work on Governor Chandler. He took his orders from the administration political headquarters in Kentucky. He put nine WPA supervisors and 340 WPA timekeepers on government time to work preparing elaborate forms for checking on all the reliefers in the district. Having done this they then proceeded to check up on the 17,000 recipients who were drawing relief money to see how they stood on the election.

In the second WPA district, another WPA official who was the area engineer managed a thorough canvass of the workers in Pulaski and Russell counties. The WPA foremen were given sheets upon which they had to report on the standing of the reliefers in the political campaign. It became a part of the WPA organization in Kentucky to learn how many of the down people on government relief had devotion to Franklin D. Roosevelt. The reliefers were asked to sign papers pledging themselves to the election of the senior senator from Kentucky. They were given campaign buttons and told to wear them and there were instances where, if they refused, they were thrown off the WPA rolls.

This occurred in a Democratic primary election where only Democrats could vote. But there were a lot of poor Republicans in Kentucky who couldn't vote in the Democratic primary so long as they were Republicans. So they were told to change their registration and become Democrats, or no WPA jobs for them.

A lady employed in the Division of Employment in WPA District 4 in Kentucky got a letter from the project superintendent asking her for a contribution to the Barkley Campaign Committee. A district supervisor of employment in District 4 told her that the election was drawing near and that she might be criticized if she did not contribute since she was employed on WPA, that she should be in sympathy with the program and be loyal and he stated also that he was a Republican but he was going to change his registration. Then he told her she would be permitted to contribute if she liked in the amount of two per cent of her salary. Letters went out from the superintendent to practically all of the reliefers. The assistant supervisor of the WPA, who got $175 a month, sent a check for $42.50 as a result of this letter and another getting $1800 a year gave $30.

Here is a sample of the letter sent out. It was from the project superintendent for whom these people worked:

- "We know that you, as a friend of the National Administration, are anxious to see Senator Barkley reelected as he has supported the President in all New Deal legislation ... If Senator Barkley is nominated and elected by a large majority there is definite possibility of his being the candidate of the Democratic party in 1940. Think what this would mean for Kentucky.

- "We know you will appreciate the opportunity of being given a chance to take an active part in reelecting Senator Barkley by making a liberal contribution towards his campaign expenses. Such contribution is actually underwriting a continuance of New Deal policies."

Reliefers were allowed to pay on the installment plan. The letter went on:

- "As the enclosed subscription blank indicates, you may pay onehalf of your contribution now and the balance by July 16."

Worker after worker testified that he received the above letter or one like it and had made contributions in proportion to the pay he was getting, usually about two per cent.

Pennsylvania[edit]

In Pennsylvania, where Senator Joe Guffey presided over the destinies of the Democratic party, the story was much the same. Men who supplied trucks to WPA were solicited for $100 each in Carbon County. The owners of the trucks were requested by WPA officials to visit representatives of certain political leaders at their homes. Ten or twelve at a time went and many of them contributed. In Lucerne County it was the same. They were told to call at Democratic headquarters and make their contributions. In Montgomery County, the WPA workers got letters stating that at the direction of the senator from Pennsylvania (Guffey) and the state committeeman, a joint meeting of WPA workers would be held on a certain date and they were told "there will be no excuse accepted for lack of attendance."

The evidence showed that WPA workers in this county, including timekeepers and poor women on sewing projects, were requested and ordered to change their registration from Republican to Democratic and in many cases those who refused were fired.[11] There was testimony that there were a number of Republicans on the WPA project near Wilkes Barre. They lived in Wilkes Barre and they thought they had a right to continue to be Republicans. They soon discovered that the right had vanished when they became wards of the New Deal and as punishment, 18 were transferred from the project near Wilkes Barre to a project 35 or 40 miles from their homes because they refused to discard their Republican buttons.

In Pennsylvania workcards were issued by the Party entitling the recipients to employment on the state highways and these were distributed by political groups. Some of these cards entitled the holders to employment "for two to four weeks around election time." In one county, from September, 1935 to September, 1938, the WPA spent more than $27,000,000 on highways.

A man in Plymouth, Pa., was given a white collar relief job before election at $60.50 a month. He was told to change his registration from Republican to Democratic. He refused and very soon found himself transferred from a white collar job to a pickaxe job on a rock pile in a quarry. There he discovered others on the rock pile who had refused to change their registration.

Ten days before the Pennsylvania primary registrations a letter signed by Democratic leader of the 14th ward in Philadelphia was issued which read,

- Dear Committeemen :

- Contact all houses in your division and get the names of all men on relief, also of those holding WPA jobs. Urge them to register Democratic on March 26 or else lose their jobs.[12]

Tennessee[edit]

It was the same in Tennessee where the WPA was lighting a fire under Governor Browning.[13] Reliefers who were for Browning if it could be proved were dropped from the payroll. They were asked for contributions of two per cent. One man was asked to put up $5. He didn't have it. He was summoned the next day. The collector had decided to reduce his tribute to $3. He didn't have that. He was told to get it. He had to borrow it. Another, assessed twice before, rebelled. "You don't have to pay," he was told, "but if you don't you'll have a hell of a time getting on the WPA." African-Americans on relief were made to put up 25 and 50 cents.

Illinois[edit]

In Cook County, Illinois, where Mayor Kelly and Party Chairman Nash carried the New Deal banner, 450 men were employed in one election district and dismissed the day after election. Seventy reported to do highway work and were told to go to their voting precincts and canvass for votes for the Horner-Courtney-Lucas ticket. These 450 men cost $23,268.

Bibliography[edit]

Scholarly studies[edit]

- Jim Crouch, "The Works Progress Administration" Eh.Net Encyclopedia (2004)

- Amenta, Edwin and Halfmann, Drew. "Wage Wars: Institutional Politics, WPA Wages, and the Struggle for U.S. Social Policy." American Sociological Review 2000 65(4): 506-528. Issn: 0003-1224 Fulltext: in Jstor; examines key Senate roll-call votes on WPA wage rates and state-level variations in WPA wages

- Amenta, Edwin and Halfmann, Drew. "Who Voted with Hopkins? Institutional Politics and the WPA." Journal of Policy History 2001 13(2): 251-287. Issn: 0898-0306 Fulltext: online at Project Muse and Swetswise

- Blumberg, Barbara. The New Deal and the Unemployed: The View from New York City (1979)

- Hopkins, June. "The Road Not Taken: Harry Hopkins and New Deal Work Relief" Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. 29, (1999)

- Howard; Donald S. The WPA and Federal Relief Policy (1943), detailed analysis of all major WPA programs.

- Lindley, Betty Grimes and Ernest K. Lindley. A New Deal for Youth: The Story of the National Youth Administration (1938) online edition

- McJimsey George T. Harry Hopkins: Ally of the Poor and Defender of Democracy (1987)

- Meriam; Lewis. Relief and Social Security The Brookings Institution. 1946. Highly detailed analysis and statistical summary of all New Deal relief programs; 900 pages

- Millett; John D. and Gladys Ogden. Administration of Federal Work Relief 1941.

- Noun, Rosenfield Louise. Iowa Women in the WPA. Iowa State U. Press, 1999. 140 pp.

- Rose, Nancy E. Put to Work (Monthly Review Press, June 1994, ISBN 0-85345-871-5)

- Singleton, Jeff. The American Dole: Unemployment Relief and the Welfare State in the Great Depression (2000)

- Smith, Jason Scott. Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933-1956 (2005)

- Williams; Edward Ainsworth. Federal Aid for Relief 1939. online edition

Cultural projects[edit]

- Billington, Ray Allen. "Government and the Arts: the W. P. A. Experience." American Quarterly 1961 13(4): 466-479. Issn: 0003-0678 Fulltext: in Jstor; Billington was an official of the Massachusetts Writers project

- Bindas, Kenneth J. "All of This Music Belongs to the Nation: The Federal Music Project of the WPA and American Cultural Nationalism, 1935-1939." PhD dissertation U. of Toledo 1988. 309 pp. DAI 1989 50(2): 528-A. DA8909905 Fulltext: online at ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Bloxom, Marguerite D., ed. Pickaxe and Pencil: References for the Study of the WPA. Library. of Congress, 1982. 87 pp. bibliography

- Bold, Christine. The WPA Guides: Mapping America. U. Press of Mississippi, 1999. 246 pp.

- Brightman, Stacy Claire. "The Federal Theatre Project in Los Angeles." PhD dissertation U. of California, Davis 1999. 188 pp. DAI 2000 60(8): 2741-A. DA9940083 Fulltext: online at ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Browne, Lorraine. "Federal Theatre: Melodrama, Social Protest, and Genius" Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, Volume 36 No. 1, Winter 1979, p. 18-37. online edition

- Bustard, Bruce I. A New Deal for the Arts. U. of Washington Press, 1997. 133 pp.

- Craig, E. Quita. Black Drama of the Federal Theater Era: Beyond the Formal Horizons. U. of Massachusetts Press, 1980. 239 pp.

- Hirsch, Jerrold. Portrait of America: A Cultural History of the Federal Writers' Project. U. of North Carolina Press, 2003. 293 pp. online review

- Lyon, Edwin A. A New Deal for Southeastern Archaeology. U. of Alabama Press, 1996. 283 pp.

- McDonald, William F. Federal Relief Administration and the Arts: The Origins and Administrative History of the Arts Projects of the Works Progress Administration. Ohio State U. Press, 1969. 869 pp.

- Mangione, Jerre. The Dream and the Deal: The Federal Writers' Project, 1935-1943 (1972)

- Nunn, Tey Marianna. Sin Nombre: Hispana and Hispanic Artists of the New Deal Era. U. of New Mexico Press, 2001. 192 pp.

- O'Gara, Geoffrey. A Long Road Home: In the Footsteps of the WPA Writers. Houghton Mifflin, 1990. 312 pp.

- Seaton, Elizabeth Gaede. "Federal Prints and Democratic Culture: The Graphic Arts Division of the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project, 1935-1943." PhD dissertation Northwestern U. 2000. 364 pp. DAI 2000 61(6A): 2080-A. DA9974356 Fulltext: online at ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Strickland, Carol. "Posters for the People," Civilization April–May 1997 heavily illustrated online edition

External links[edit]

- Posters from the WPA at the Library of Congress

- Database of WPA murals

- Text and Graphics from 1937 WPA Brochure: "Our Job with the WPA"

- Text and Graphics from 1939 WPA Brochure: "QUESTION'S AND ANSWERS ON THE WPA"

- Samples of WPA Work Assignment Forms used in the 1930s

References[edit]

- ↑ There was some job training in the NYA, especially for occupations like domestic servants that were not unionized.

- ↑ Meriam (1946)

- ↑ Former Slave Interviews

- ↑ John Salmond, "The New Deal and the Negro" in John Braeman et al, eds. The New Deal: The National Level (1975). pp 188-89

- ↑ Howard 287

- ↑ February, 1939, p. 34. in Howard 295

- ↑ Howard p 562, paraphrasing Hopkins

- ↑ Billington, 1961

- ↑ Lindley and Lindley (1938) pp 92-93

- ↑ Facts relating to the 1938 election activities of the WPA are taken from the official report of the U. S. Senate Committee on Campaign Expenditures, quoted in The Roosevelt Myth, John T. Flynn, Fox and Wilkes, 1948, Book 1, Ch. 6, Harry the Hop and the Happy Hot Dogs

- ↑ Records on Relief, Time magazine, Oct. 19, 1936,

- ↑ Philadelphia Inquirer, March 28, 1936.

- ↑ "People Would Be Shocked!", Time magazine, Aug. 08, 1938.

Categories: [Great Depression] [New Deal] [Corruption] [Liberalism]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/24/2023 00:37:40 | 65 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Works_Progress_Administration | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF