Scrub Typhus

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki | Scrub typhus | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Bush typhus, mite typhus, jungle typhus[1] | |

| |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, muscle pain, cough, and gastrointestinal symptoms[2] |

| Causes | Orientia tsutsugamushi[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical presentation, blood test[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Typhoid,Malaria,Melioidosis, Dengue,Leptospirosis[5][6] |

| Prevention | Insect repellent containing DEET[4] |

| Medication | Doxycycline[4] |

| Frequency | 1 million cases/annually[7] |

Scrub typhus (Tsutsugamushi fever[8] or bush typhus[4]) is a form of typhus caused by the intracellular parasite Orientia tsutsugamushi, a Gram-negative α-proteobacterium of family Rickettsiaceae first isolated and identified in 1930 in Japan.[4][9]

Although the disease is similar in presentation to other forms of typhus, its pathogen is no longer included in genus Rickettsia with the typhus bacteria proper, but in Orientia. The disease is thus frequently classified separately from the other typhi.[10][11]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

Signs and symptoms include fever, headache, muscle pain, cough, and gastrointestinal symptoms. More virulent strains of O. tsutsugamushi can cause hemorrhaging and intravascular coagulation. Morbilliform rash, eschar, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathies are typical signs. Leukopenia and abnormal liver function tests are commonly seen in the early phase of the illness. Pneumonitis, encephalitis, and myocarditis occur in the late phase of illness. It has particularly been shown to be the most common cause of acute encephalitis syndrome in Bihar, India.[2][4]

-

Scrub typhus eschar

-

Macular eruption with some scattered papules on his trunk

-

Eschar in chest wall

Causes[edit | edit source]

Scrub typhus is transmitted by some species of trombiculid mites ("chiggers", particularly Leptotrombidium deliense),[12] which are found in areas of heavy scrub vegetation; the mites feed on infected rodent hosts and subsequently transmit the parasite to other rodents and humans.

The bite of this mite leaves a characteristic black eschar that is useful to the healthcare worker to evaluate.[13][14]

Scrub typhus is endemic to a part of the world known as the tsutsugamushi triangle (after O. tsutsugamushi).[9]

This extends from northern Japan and far-eastern Russia in the north, to the territories around the Solomon Sea into northern Australia in the south, and to Pakistan and Afghanistan in the west.[15]

It may also be endemic in parts of South America.[16]

Mechanism[edit | edit source]

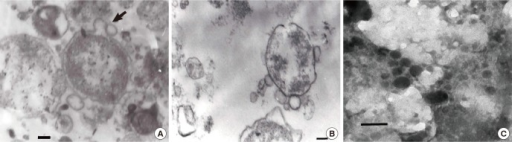

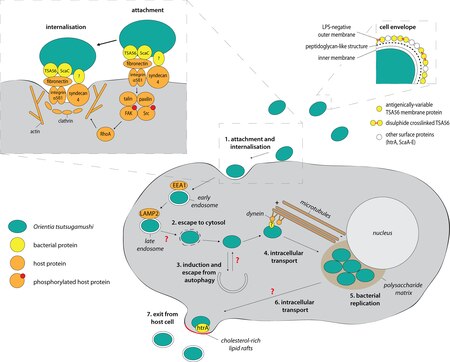

Orientia tsutsugamushi initially attacks the myelocytes in the area of inoculation, and then the endothelial cells lining the vasculature. In the blood circulation, it targets professional phagocytes such as dendritic cells and macrophages in all organs as the secondary targets. The parasite first attaches itself to the target cells using surface proteoglycans present on the host cell and bacterial surface proteins such as type specific protein 56 or type specific antigen, TSA56 and surface cell antigens ScaA and ScaC, which are membrane transporter proteins.[18][19]

These proteins interact with the host fibronectin to induce phagocytosis (the process of ingesting the bacterium). The ability to actually enter the host cell depends on integrin-mediated signaling and reorganisation of the actin cytoskeleton.[20]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

In endemic areas, diagnosis is generally made on clinical grounds alone. However, overshadowing of the diagnosis is quite often as the clinical symptoms overlap with other infectious diseases such as dengue fever, paratyphoid, and pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO). If the eschar can be identified, it is quite diagnostic of scrub typhus, but this can be unreliable on dark skin, and moreover, the site of eschar which is usually where the mite bites is often located in covered areas. Unless it is actively searched for, the eschar can easily be missed. History of mite bite is often absent since the bite does not inflict pain and the mites are almost too small to be seen by the naked eye. Usually, scrub typhus is often labelled as PUO in remote endemic areas, since blood culture is often negative, yet it can be treated effectively with chloramphenicol. Where doubt exists, the diagnosis may be confirmed by a laboratory test such as serology.[21][22][23][24]

The choice of laboratory test is not straightforward, and all currently available tests have their limitations.[25] The cheapest and most easily available serological test is the Weil-Felix test, but this is notoriously unreliable.[26] The gold standard is indirect immunofluorescence,[27] but the main limitation of this method is the availability of fluorescent microscopes, which are not often available in resource-poor settings where scrub typhus is endemic. Indirect immunoperoxidase, a modification of the standard IFA method, can be used with a light microscope,[28] and the results of these tests are comparable to those from IFA.[26][29] Rapid bedside kits have been described that produce a result within one hour, but the availability of these tests is severely limited by their cost.[26] Serological methods are most reliable when a four-fold rise in antibody titre is found. If the patient is from a nonendemic area, then diagnosis can be made from a single acute serum sample.[30] In patients from endemic areas, this is not possible because antibodies may be found in up to 18% of healthy individuals.[31]

Other methods include culture and polymerase chain reaction, but these are not routinely available[32] and the results do not always correlate with serological testing,[33][34][35] and are affected by prior antibiotic treatment.[36] The currently available diagnostic methods have been summarised.[25]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Without treatment, the disease is often fatal. Since the use of antibiotics, case fatalities have decreased from 4–40% to less than 2%.[37][38]

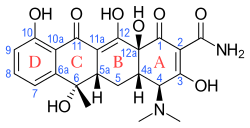

The drug most commonly used is doxycycline or tetracycline, but chloramphenicol is an alternative. Strains that are resistant to doxycycline and chloramphenicol have been reported in northern Thailand.[39][40] Rifampicin[41] and azithromycin[42] are alternatives. Azithromycin is an alternative in children[43] and pregnant women with scrub typhus,[44][45][46] and when doxycycline resistance is suspected.[47] Ciprofloxacin cannot be used safely in pregnancy and is associated with stillbirths and miscarriage.[46][48] Combination therapy with doxycycline and rifampicin is not recommended due to possible antagonism.[49]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The precise incidence of the disease is unknown, as diagnostic facilities are not available in much of its large native range, which spans vast regions of equatorial jungle to the subtropics. In rural Thailand and Laos, murine and scrub typhus account for around a quarter of all adults presenting to hospital with fever and negative blood cultures.[50][51] The incidence in Japan has fallen over the past few decades, probably due to land development driving decreasing exposure, and many prefectures report fewer than 50 cases per year.[52][53]

It affects females more than males in Korea, but not in Japan,[54] which may be because sex-differentiated cultural roles have women tending garden plots more often, thus being exposed to vegetation inhabited by chiggers. The incidence is increasing in the southern part of the Indian subcontinent [55]

Scrub typhus is historically endemic to the Asia-Pacific region, covering the Russian Far East and Korea in the north, to northern Australia in the south, and Afghanistan in the west, including islands of the western Pacific Oceans such as Japan, Taiwan, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Subcontinent.[56]

However, it has spread to Africa, Europe and South America.[57]

History[edit | edit source]

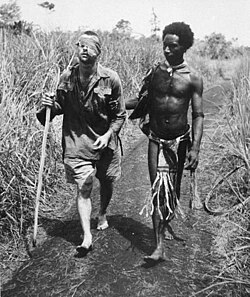

Severe epidemics of the disease occurred among troops in Burma and Ceylon during World War II.[58]

Several members of the U.S. Army's 5307th Composite Unit, Merrill's Marauders, died of the disease, as well as many soldiers in the Burma theatre[59]; and before 1944, no effective antibiotics or vaccines were available.[60][61]

World War II provides some indicators that the disease is endemic to undeveloped areas in all of Oceania in the Pacific theater, although war records frequently lack definitive diagnoses, and many records of "high fever" evacuations were also likely to be other tropical illnesses. In the chapter entitled "The Green War", General MacArthur's biographer William Manchester identifies that the disease was one of a number of debilitating afflictions affecting both sides on New Guinea[62] in the running bloody Kokoda battles over extremely harsh terrains under intense hardships— fought during a six-month span[63] all along the Kokoda Track in 1942–43, and mentions that to be hospital-evacuated, Allied soldiers had to run a fever of 102 °F (39 °C), and that sickness casualties outnumbered weapons-inflicted casualties 5:1.[62]

The disease was also a problem for US troops stationed in Japan after WWII, and was variously known as "Shichitō fever", by troops stationed in the Izu Seven Islands, or "Hatsuka fever" .[64]

Scrub typhus was first reported in Chile in 2006.[65]

This is likely the result of underdiagnosis and underreporting and not of a recent spread to Chile.[65] In January 2020 the disease was for the first time reported in Chile's southernmost region.[65]

Research[edit | edit source]

No licensed vaccines are available.[66]An early attempt to create a scrub typhus vaccine occurred in the United Kingdom in 1937 (with the Wellcome Foundation infecting around 300,000 cotton rats in a classified project called "Operation Tyburn"), but the vaccine was not used.[67] The first known batch of scrub typhus vaccine actually used to inoculate human subjects was dispatched to India for use by Allied Land Forces, South-East Asia Command in June 1945. By December 1945, 268,000 cc had been dispatched.[68] The vaccine was produced at Wellcome's laboratory at Ely Grange, Frant, Sussex. An attempt to verify the efficacy of the vaccine by using a placebo group for comparison was vetoed by the military commanders, who objected to the experiment.[69]

Enormous antigenic variation in Orientia tsutsugamushi strains is now recognized,[70][71] and immunity to one strain does not confer immunity to another. Any scrub typhus vaccine should give protection to all the strains present locally, to give an acceptable level of protection. A vaccine developed for one locality may not be protective in another, because of antigenic variation. This complexity continues to hamper efforts to produce a viable vaccine.[72]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Slim, William (1956). Defeat Into Victory. London: Sassell. p. 177.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Jain P; Prakash S; Tripathi PK; et al. (2018). "Emergence of Orientia tsutsugamushi as an important cause of acute encephalitis syndrome in India". PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 12 (3): e0006346. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006346. PMC 5891077. PMID 29590177.

- ↑ Salje, J.; Kline, K.A. (2017). "Orientia tsutsugamushi: A neglected but fascinating obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen". PLOS Pathogens. 13 (12): e1006657. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006657. PMC 5720522. PMID 29216334.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Scrub typhus | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 November 2020. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ↑ "Scrub typhus | DermNet". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ↑ Nachega, Jean B.; Bottieau, Emmanuel; Zech, Francis; Van Gompel, Alfons (2007). "Travel-acquired scrub typhus: emphasis on the differential diagnosis, treatment, and prevention strategies". Journal of Travel Medicine. 14 (5): 352–355. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2007.00151.x. ISSN 1195-1982. Archived from the original on 2022-11-25. Retrieved 2023-08-06.

- ↑ Xu, G; Walker, DH; Jupiter, D; Melby, PC; Arcari, CM (November 2017). "A review of the global epidemiology of scrub typhus". PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 11 (11): e0006062. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006062. PMID 29099844. Archived from the original on 1 August 2023. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ↑ "Scrub typhus (Concept Id: C0036472) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 30 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Pediatric Scrub Typhus Archived 2017-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, accessdate: 16 October 2011

- ↑ Rapsang, AG; Bhattacharyya, P (March 2013). "Scrub typhus". Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 57 (2): 127–34. doi:10.4103/0019-5049.111835. PMC 3696258. PMID 23825810.

- ↑ Walker, David H. (1996). "Rickettsiae". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Archived from the original on 2023-07-02. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ↑ Pham XD, Otsuka Y, Suzuki H, Takaoka H (2001). "Detection of Orientia tsutsugamushi (Rickettsiales: Rickettsiaceae) in unengorged chiggers (Acari: Trombiculidae) from Oita Prefecture, Japan, by nested polymerase chain reaction". J Med Entomol. 38 (2): 308–311. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-38.2.308. PMID 11296840. S2CID 8133110.

- ↑ Pedro N. Acha; Boris Szyfres (2003). Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals: Chlamydioses, rickettsioses, and viroses. Pan American Health Org. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-92-75-11992-1. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ↑ Diaz, James H. (1 January 2015). "297 - Mites, Including Chiggers". Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (Eighth ed.). W.B. Saunders. pp. 3260–3265.e1. ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ↑ Seong SY, Choi MS, Kim IS (January 2001). "Orientia tsutsugamushi infection: overview and immune responses". Microbes Infect. 3 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01352-6. PMID 11226850.

- ↑ Deadly scrub typhus bacteria confirmed in South America Archived 2019-09-23 at the Wayback Machine. ScienMag (September 8, 2016)

- ↑ Salje, Jeanne (7 December 2017). "Orientia tsutsugamushi: A neglected but fascinating obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen". PLOS Pathogens. 13 (12): e1006657. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006657. ISSN 1553-7374. PMC 5720522. PMID 29216334. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ↑ Ge, Y.; Rikihisa, Y. (2011). "Subversion of host cell signaling by Orientia tsutsugamushi". Microbes and Infection. 13 (7): 638–648. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2011.03.003. PMID 21458586.

- ↑ Ha, N.Y.; Sharma, P.; Kim, G.; Kim, Y.; Min, C.K.; Choi, M.S.; Kim, I.S.; Cho, N.H. (2015). "Immunization with an autotransporter protein of Orientia tsutsugamushi provides protective immunity against scrub typhus". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 9 (3): e0003585. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003585. PMC 4359152. PMID 25768004.

- ↑ Cho, B. A.; Cho, N. H.; Seong, S. Y.; Choi, M. S.; Kim, I. S. (2010). "Intracellular invasion by Orientia tsutsugamushi is mediated by integrin signaling and actin cytoskeleton rearrangements". Infection and Immunity. 78 (5): 1915–1923. doi:10.1128/IAI.01316-09. PMC 2863532. PMID 20160019.

- ↑ "Scrub Typhus - Infections". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ↑ Chakraborty, S; Sarma, N (September 2017). "Scrub Typhus: An Emerging Threat". Indian Journal of Dermatology. 62 (5): 478–485. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_388_17 (inactive 2023-08-03). PMC 5618834. PMID 28979009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - ↑ Kala, Deepak; Gupta, Shagun; Nagraik, Rupak; Verma, Vivek; Thakur, Atul; Kaushal, Ankur (September 2020). "Diagnosis of scrub typhus: recent advancements and challenges". 3 Biotech. 10 (9): 396. doi:10.1007/s13205-020-02389-w. ISSN 2190-572X. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ↑ Eiben, Inez; Eiben, Paola; Watson, Kathryn (2019). "8. Pyrexia of unknown origin". Crash Course General Medicine (5th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-0-7020-7372-4. Archived from the original on 2022-05-09. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Koh GC, Maude RJ, Paris DH, Newton PN, Blacksell SD (March 2010). "Diagnosis of scrub typhus". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 82 (3): 368–70. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0233. PMC 2829893. PMID 20207857.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Pradutkanchana J, Silpapojakul K, Paxton H, et al. (1997). "Comparative evaluation of four serodiagnostic tests for scrub typhus in Thailand". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 91 (4): 425–8. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(97)90266-2. PMID 9373640.

- ↑ Bozeman FM & Elisberg BL (1963). "Serological diagnosis of scrub typhus by indirect immunofluorescence". Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 112 (3): 568–73. doi:10.3181/00379727-112-28107. PMID 14014756. S2CID 44692835.

- ↑ Yamamoto S & Minamishima Y (1982). "Serodiagnosis of tsutsugamushi fever (scrub typhus) by the indirect immunoperoxidase technique". J Clin Microbiol. 15 (6): 1128–l. doi:10.1128/JCM.15.6.1128-1132.1982. PMC 272264. PMID 6809786.

- ↑ Kelly DJ, Wong PW, Gan E, Lewis GE Jr (1988). "Comparative evaluation of the indirect immunoperoxidase test for the serodiagnosis of rickettsial disease". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 38 (2): 400–6. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.400. PMID 3128129.

- ↑ Blacksell SD, Bryant NJ, Paris, DH, et al. (2007). "Scrub typhus serologic testing with the indirect immunofluorescence method as a diagnostic gold standard: a lack of consensus leads to a lot of confusion". Clin Infect Dis. 44 (3): 391–401. doi:10.1086/510585. PMID 17205447.

- ↑ Eamsila C, Singsawat P, Duangvaraporn A, et al. (1996). "Antibodies to Orientia tsutsugamushi in Thai soldiers". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 55 (5): 556–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.556. PMID 8940989.

- ↑ Watt G, Parola P (2003). "Scrub typhus and tropical rickettsioses". Curr Opin Infect Dis. 16 (5): 429–436. doi:10.1097/00001432-200310000-00009. PMID 14501995. S2CID 24087729.

- ↑ Tay ST, Nazma S, Rohani MY (1996). "Diagnosis of scrub typhus in Malaysian aborigines using nested polymerase chain reaction". Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 27 (3): 580–3. PMID 9185274.

- ↑ Kim, DM; Yun, NR; Yang, TY; Lee, JH; Yang, JT; Shim, SK; Choi, EN; Park, MY; Lee, SH (2006). "Usefulness of nested PCR for the diagnosis of scrub typhus in clinical practice: A prospective study". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 75 (3): 542–545. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.542. PMID 16968938.

- ↑ Sonthayanon P, Chierakul W, Wuthiekanun V, et al. (December 2006). "Rapid diagnosis of scrub typhus in rural Thailand using polymerase chain reaction". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 75 (6): 1099–102. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.1099. PMID 17172374.

- ↑ Kim DM, Byun JN (2008). "Effects of Antibiotic Treatment on the Results of Nested PCRs for Scrub Typhus". J Clin Microbiol. 46 (10): 3465–. doi:10.1128/JCM.00634-08. PMC 2566087. PMID 18716229.

- ↑ Yang, J; Luo, L; Chen, T; Li, L; Xu, X; Zhang, Y; Cao, W; Yue, P; Bao, F; Liu, A (3 August 2020). "Efficacy and Safety of Antibiotics for Treatment of Scrub Typhus: A Network Meta-analysis". JAMA network open. 3 (8): e2014487. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14487. PMID 32857146. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ↑ Dubey, Sneha R. (7 May 2019). "Scrub Typhus". International Journal of Nursing Education and Research. 7 (2): 287–290. doi:10.5958/2454-2660.2019.00066.8. Archived from the original on 8 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ↑ Watt G, Chouriyagune C, Ruangweerayud R, et al. (1996). "Scrub typhus infections poorly responsive to antibiotics in northern Thailand". Lancet. 348 (9020): 86–89. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)02501-9. PMID 8676722. S2CID 23316592.

- ↑ Kollars TM, Bodhidatta D, Phulsuksombati D, et al. (2003). "Short report: variation in the 56-kD type-specific antigen gene of Orientia tsutsugamushi isolated from patients in Thailand". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 68 (3): 299–300. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.299. PMID 12685633.

- ↑ El Sayed, Iman; Liu, Qin; Wee, Ian; Hine, Paul (24 September 2018). "Antibiotics for treating scrub typhus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (9): CD002150. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002150.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6485465. PMID 30246875.

- ↑ Phimda K, Hoontrakul S, Suttinont C, et al. (2007). "Doxycycline versus Azithromycin for Treatment of Leptospirosis and Scrub Typhus". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 51 (9): 3259–63. doi:10.1128/AAC.00508-07. PMC 2043199. PMID 17638700.

- ↑ Mahajan SK, Rolain JM, Sankhyan N, Kaushal RK, Raoult D (2008). "Pediatric scrub typhus in Indian Himalayas". Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 75 (9): 947–9. doi:10.1007/s12098-008-0198-z. PMID 19011809. S2CID 207384950.

- ↑ Watt, G; Kantipong, P; Jongsakul, K; Watcharapichat, P; Phulsuksombati, D (1999). "Azithromycin Activities against Orientia tsutsugamushi Strains Isolated in Cases of Scrub Typhus in Northern Thailand". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 43 (11): 2817–2818. doi:10.1128/AAC.43.11.2817. PMC 89570. PMID 10543774.

- ↑ Choi EK, Pai H (1998). "Azithromycin therapy for scrub typhus during pregnancy". Clin Infect Dis. 27 (6): 1538–9. doi:10.1086/517742. PMID 9868680.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Kim YS, Lee HJ, Chang M, Son SK, Rhee YE, Shim SK (2006). "Scrub typhus during pregnancy and its treatment: a case series and review of the literature". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 75 (5): 955–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2006.75.955. PMID 17123995.

- ↑ <Please add first missing authors to populate metadata.> (2003). "Efficacy of azithromycin for treatment of mild scrub-typhus infections in South Korea". Abstr Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 43: abstract no. L–182.

- ↑ Mathai E, Rolain JM, Verghese L, Mathai M, Jasper P, Verghese G, Raoult D (2003). "Case reports: scrub typhus during pregnancy in India". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 97 (5): 570–2. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(03)80032-9. PMID 15307429.

- ↑ Watt G, Kantipong P, Jongsakul K, et al. (2000). "Doxycycline and rifampicin for mild scrub-typhus infections in northern Thailand: a randomised trial". Lancet. 356 (9235): 1057–1061. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02728-8. PMID 11009140. S2CID 29646085.

- ↑ Phongmany S, Rolain JM, Phetsouvanh R, et al. (February 2006). "Rickettsial infections and fever, Vientiane, Laos". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (2): 256–62. doi:10.3201/eid1202.050900. PMC 3373100. PMID 16494751.

- ↑ Suttinont C, Losuwanaluk K, Niwatayakul K, et al. (June 2006). "Causes of acute, undifferentiated, febrile illness in rural Thailand: results of a prospective observational study". Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 100 (4): 363–70. doi:10.1179/136485906X112158. PMID 16762116. S2CID 25778287.

- ↑ Katayama T, Hara M, Furuya Y, Nikkawa T, Ogasawara H (June 2006). "Scrub typhus (tsutsugamushi disease) in Kanagawa Prefecture in 2001–2005". Jpn J Infect Dis. 59 (3): 207–8. PMID 16785710. Archived from the original on 2010-05-25.

- ↑ Yamamoto S, Ganmyo H, Iwakiri A, Suzuki S (December 2006). "Annual incidence of tsutsugamushi disease in Miyazaki prefecture, Japan in 2001-2005". Jpn J Infect Dis. 59 (6): 404–5. PMID 17186964. Archived from the original on 2009-08-15.

- ↑ Bang HA, Lee MJ, Lee WC (2008). "Comparative research on epidemiological aspects of tsutsugamushi disease (scrub typhus) between Korea and Japan". Jpn J Infect Dis. 61 (2): 148–50. doi:10.7883/yoken.JJID.2008.148. PMID 18362409. S2CID 24683749. Archived from the original on 2008-09-27.

- ↑ Devasagayam, Emily; Dayanand, Divya; Kundu, Debasree; Kamath, Mohan S.; Kirubakaran, Richard; Varghese, George M. (27 July 2021). "The burden of scrub typhus in India: A systematic review". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 15 (7): e0009619. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009619. ISSN 1935-2735. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ↑ Peter, JV; Sudarsan, TI; Prakash, JA; Varghese, GM (4 August 2015). "Severe scrub typhus infection: Clinical features, diagnostic challenges and management". World Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 4 (3): 244–50. doi:10.5492/wjccm.v4.i3.244. PMC 4524821. PMID 26261776.

- ↑ Jiang, J.; Richards, A.L. (2018). "Scrub typhus: No longer restricted to the Tsutsugamushi Triangle". Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 3 (1): 11. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed3010011. PMC 6136623. PMID 30274409.

- ↑ Audy JR (1968). Red mites and typhus. London: University of London, Athlone Press. ISBN 978-0-485-26318-3.

- ↑ Grant, Ian Lyall- (2003). Burma: The Turning Point. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Leo Cooper. p. 212. ISBN 1-84415-026-7.

- ↑ Kearny CH (1997). Jungle Snafus...And Remedies. Cave Junction, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Science & Medicine. p. 309. ISBN 978-1-884067-10-5.

- ↑ Smallman-Raynor M, Cliff AD (2004). War epidemics: an historical geography of infectious diseases in military conflict and civil strife, 1850–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 489–91. ISBN 978-0-19-823364-0.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 William Manchester (1978). "The Green War". American Caesar. Little Brown Company. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-0-316-54498-6.

- ↑ Manchester, p. Six months to recapture Buna and Gona from July 21–22, 1942

- ↑ Ogawa M, Hagiwara T, Kishimoto T, et al. (1 August 2002). "Scrub typhus in Japan: Epidemiology and clinical features of cases reported in 1998". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 67 (2): 162–5. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.162. PMID 12389941.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 González, C. (January 29, 2020). "Una bacteria presente en ácaros causa un raro tipo de infección en el sur". El Mercurio (in español). p. A9.

- ↑ Arguin PM, Kozarsky PE, Reed C (2008). "Chapter 4: Rickettsial Infections". CDC Health Information for International Travel, 2008. Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-04885-9. Archived from the original on 2009-05-06. Retrieved 2021-10-16.

- ↑ "AWIC Newsletter: The Cotton Rat In Biomedical Research". Archived from the original on 2004-06-10.

- ↑ "Scrub Typhus Vaccine, Far East". Hansard. Millbanksystems. April 2, 1946. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ↑ Thomson Walker W (1947). "Scrub Typhus Vaccine". Br Med J. 1 (4501): 484–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4501.484. PMC 2053023. PMID 20248030.

- ↑ Shirai A, Tanskul PL, Andre, RG, et al. (1981). "Rickettsia tsutsugamushi strains found in chiggers collected in Thailand". Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 12 (1): 1–6. PMID 6789455.

- ↑ Kang JS, Chang WH (1999). "Antigenic relationship among the eight prototype and new serotype strains of Orientia tsutsugamushi revealed by monoclonal antibodies". Microbiol Immunol. 43 (3): 229–34. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02397.x. PMID 10338191. S2CID 41165633.

- ↑ Kelly DJ, Fuerst PA, Ching WM, Richards AL (2009). "Scrub typhus: The geographic distribution of phenotypic and genotypic variants of Orientia tsutsugamushi". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (s3): S203–30. doi:10.1086/596576. PMID 19220144.

External links[edit | edit source]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Categories: [Typhus] [Bacterium-related cutaneous conditions] [Zoonoses] [Tick-borne diseases]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 04/22/2024 14:53:49 | 2 views

☰ Source: https://mdwiki.org/wiki/Scrub_typhus | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

KSF

KSF