Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

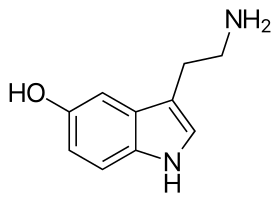

Serotonin, the neurotransmitter that is involved in the mechanism of action of SSRIs. | |

| Names | |

| Stem | -oxetine[2] |

| Other names | Serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors, serotonergic antidepressants[1] |

| Clinical data | |

| Uses | Depression, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder[3] |

| Side effects | Upset stomach, allergies, weight change, suicide, bleeding[3] |

| Interactions | MAO inhibitors, other serotonergic medication.[3] |

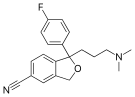

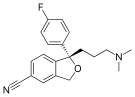

| Common types | Citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline[3][4] |

| Biological target | Serotonin transporter[5] |

| External links | |

| Drugs.com | Drug Classes |

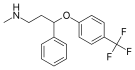

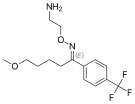

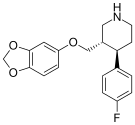

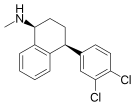

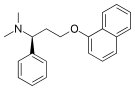

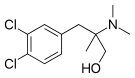

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a class of medication that is typically used for depression, panic disorder, and obsessive compulsive disorder.[3] The benefit in depression; however, is small and may be outweighed by side effects, especially in younger people.[6][7] Effectiveness is similar to that of tricyclic antidepressants.[3]

Common side effects include an upset stomach, allergies, and weight change.[3] Other side effects may include low sodium, bleeding, and suicide.[3] Overdose may result in serotonin syndrome.[3] Stopping suddenly can result in withdrawal.[3] SSRIs are believed to work by increasing levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin by limiting its reuptake.[3]

SSRIs, specifically fluoxetine, were first approved for medical use in the United States in 1987.[8] They are the most commonly used antidepressants in many countries, including the USA.[9][10] A number of SSRIs are available as generic medications and are relatively inexpensive.[3]

Types[edit | edit source]

Marketed[edit | edit source]

- Citalopram (Celexa)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro)

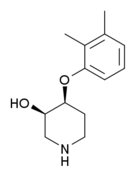

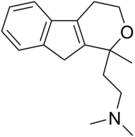

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox)

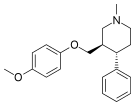

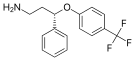

- Paroxetine (Paxil)

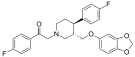

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

- Dapoxetine (Priligy)

Discontinued[edit | edit source]

- Indalpine (Upstène)

- Zimelidine (Zelmid)

Never marketed[edit | edit source]

- Alaproclate (GEA-654)

- Centpropazine

- Cericlamine (JO-1017)

- Femoxetine (Malexil; FG-4963)

- Ifoxetine (CGP-15210)

- Omiloxetine

- Panuramine (WY-26002)

- Pirandamine (AY-23713)

- Seproxetine ((S)-norfluoxetine)

Related medications[edit | edit source]

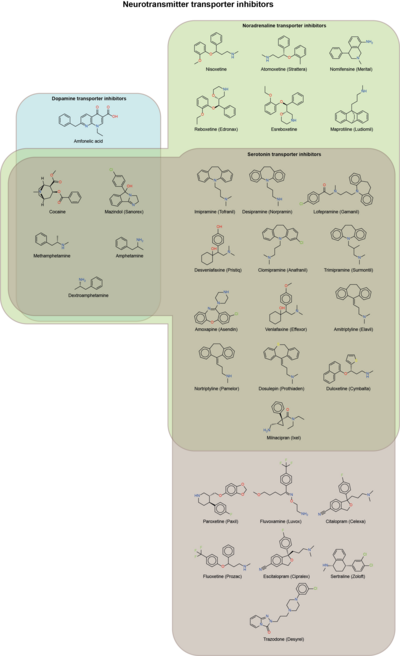

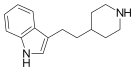

Although described as SNRIs, duloxetine, venlafaxine, and desvenlafaxine are relatively selective as serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs).[11] They are about at least 10-fold selective for inhibition of serotonin reuptake over norepinephrine reuptake.[11] The selectivity ratios are approximately 1:30 for venlafaxine, 1:10 for duloxetine, and 1:14 for desvenlafaxine.[11][12] At low doses, these SNRIs act mostly as SSRIs; only at higher doses do they also prominently inhibit norepinephrine reuptake.[13][14] Milnacipran and its stereoisomer levomilnacipran are the only widely marketed SNRIs that inhibit serotonin and norepinephrine to similar degrees, both with ratios close to 1:1.[11][15]

Vilazodone and vortioxetineare SRIs that also act as modulators of serotonin receptors and are described as serotonin modulators and stimulators (SMS).[16] Vilazodone is a 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist while vortioxetine is a 5-HT1A receptor agonist and 5-HT3 and 5-HT7 receptor antagonist.[16] Litoxetine and lubazodone are similar drugs that were never marketed.[17][18][19][20] They are SRIs and litoxetine is also a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist[17][18] while lubazodone is also a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist.[19][20]

Medical uses[edit | edit source]

The main indication for SSRIs is major depressive disorder; however, they are frequently prescribed for anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), eating disorders, chronic pain, and, in some cases, for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). They are also frequently used to treat depersonalization disorder, although with varying results.[21]

Depression[edit | edit source]

Antidepressants are recommended by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as a first-line treatment of severe depression and for the treatment of mild-to-moderate depression that persists after conservative measures such as cognitive therapy.[22] They recommend against their routine use in those who have chronic health problems and mild depression.[22]

There has been controversy regarding the efficacy of antidepressants in treating depression depending on its severity and duration.

- Two meta-analyses published in 2008 (Kirsch) and 2010 (Fournier) found that in mild and moderate depression, the effect of SSRIs is small or none compared to placebo, while in very severe depression the effect of SSRIs is between "relatively small" and "substantial".[23][24] The 2008 meta-analysis combined 35 clinical trials submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before licensing of four newer antidepressants (including the SSRIs paroxetine and fluoxetine, the non-SSRI antidepressant nefazodone, and the serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine). The authors attributed the relationship between severity and efficacy to a reduction of the placebo effect in severely depressed patients, rather than an increase in the effect of the medication.[24] Some researchers have questioned the statistical basis of this study suggesting that it underestimates the effect size of antidepressants.[25][26]

- A 2010 comprehensive review conducted by NICE concluded that antidepressants have no advantage over placebo in the treatment of short-term mild depression, but that the available evidence supported the use of antidepressants in the treatment of persistent depressive disorder and other forms of chronic mild depression.[27]

- A 2012 meta-analysis of fluoxetine and venlafaxine concluded that statistically and clinically significant treatment effects were observed for each drug relative to placebo irrespective of baseline depression severity; some of the authors however disclosed substantial relationships with pharmaceutical industries.[28]

- In 2014, the US FDA published a systematic review of all antidepressant maintenance trials submitted to the agency between 1985 and 2012. The authors concluded that maintenance treatment reduced the risk of relapse by 52% compared to placebo, and that this effect was primarily due to recurrent depression in the placebo group rather than a drug withdrawal effect.[29]

- A 2017 systematic review stated that "SSRIs versus placebo seem to have statistically significant effects on depressive symptoms, but the clinical significance of these effects seems questionable and all trials were at high risk of bias. Furthermore, SSRIs versus placebo significantly increase the risk of both serious and non-serious adverse events. Our results show that the harmful effects of SSRIs versus placebo for major depressive disorder seem to outweigh any potentially small beneficial effects".[30] Fredrik Hieronymus et al. criticized the review as inaccurate and misleading, but they also disclosed multiple ties to pharmaceutical industries.[31]

- In 2018, a review of 21 different antidepressants found that all analysed antidepressants were more efficacious than placebo in adults with major depressive disorder.[32] Effect sizes measured at 8-weeks after treatment onset however were modest.[32]

There does not appear to be a difference in effectiveness between medications in the second generation antidepressants (SSRIs and SNRIs).[33]

In children, there are concerns around the quality of the evidence on the meaningfulness of benefits seen.[34] If a medication is used, fluoxetine appears to be first line.[34]

Benefits may take 6 to 8 weeks to occur, and there is no evidence that higher doses are better than lower doses during that time.[35]

Social anxiety disorder[edit | edit source]

Some SSRIs are effective for social anxiety disorder, although their effects on symptoms is not always robust and their use is sometimes rejected in favor of psychological therapies. Paroxetine was the first drug to be approved for social anxiety disorder and it is considered effective for this disorder, sertraline and fluvoxamine were later approved for it, too, escitalopram and citalopram are used off label with acceptable efficacy, while fluoxetine is not considered to be effective for this disorder.[36]

Post-traumatic stress disorder[edit | edit source]

PTSD is relatively hard to treat and generally treatment is not highly effective; SSRIs are no exception. They are not very effective for this disorder and only two SSRI are FDA approved for this condition, paroxetine and sertraline. Paroxetine has slightly higher response and remission rates for PTSD than sertraline, but both are not fully effective for many patients.[citation needed] Fluoxetine is used off label, but with mixed results, venlafaxine, an SNRI, is considered somewhat effective, although used off label, too. Fluvoxamine, escitalopram and citalopram are not well tested in this disorder. Paroxetine remains the most suitable drug for PTSD as of now, but with limited benefits.[37]

Generalized anxiety disorder[edit | edit source]

SSRIs are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) that has failed to respond to conservative measures such as education and self-help activities. GAD is a common disorder of which the central feature is excessive worry about a number of different events. Key symptoms include excessive anxiety about multiple events and issues, and difficulty controlling worrisome thoughts that persists for at least 6 months.

Antidepressants provide a modest-to-moderate reduction in anxiety in GAD,[38] and are superior to placebo in treating GAD. The efficacy of different antidepressants is similar.[38]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder[edit | edit source]

In Canada, SSRIs are a first-line treatment of adult obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). In the UK, they are first-line treatment only with moderate to severe functional impairment and as second line treatment for those with mild impairment, though, as of early 2019, this recommendation is being reviewed.[39] In children, SSRIs can be considered a second line therapy in those with moderate-to-severe impairment, with close monitoring for psychiatric adverse effects.[40] SSRIs, especially fluvoxamine, which is the first one to be FDA approved for OCD, are efficacious in its treatment; patients treated with SSRIs are about twice as likely to respond to treatment as those treated with placebo.[41][42] Efficacy has been demonstrated both in short-term treatment trials of 6 to 24 weeks and in discontinuation trials of 28 to 52 weeks duration.[43][44][45]

Panic disorder[edit | edit source]

Paroxetine CR was superior to placebo on the primary outcome measure. In a 10-wk randomized controlled, double-blind trial escitalopram was more effective than placebo.[46] Fluvoxamine, another SSRI, has shown positive results.[47] However, evidence for their effectiveness and acceptability is unclear.[48]

Eating disorders[edit | edit source]

Antidepressants are recommended as an alternative or additional first step to self-help programs in the treatment of bulimia nervosa.[49] SSRIs (fluoxetine in particular) are preferred over other anti-depressants due to their acceptability, tolerability, and superior reduction of symptoms in short-term trials. Long-term efficacy remains poorly characterized.

Similar recommendations apply to binge eating disorder.[49] SSRIs provide short-term reductions in binge eating behavior, but have not been associated with significant weight loss.[50]

Clinical trials have generated mostly negative results for the use of SSRIs in the treatment of anorexia nervosa.[51] Treatment guidelines from the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence[49] recommend against the use of SSRIs in this disorder. Those from the American Psychiatric Association note that SSRIs confer no advantage regarding weight gain, but that they may be used for the treatment of co-existing depressive, anxiety, or OCD.[50]

Stroke recovery[edit | edit source]

SSRIs have been used in the treatment of stroke patients, including those with and without symptoms of depression. A 2019 meta-analysis of randomized, controlled clinical trials found a statistically significant effect of SSRIs on dependence, neurological deficit, depression, and anxiety but the studies had a high risk of bias. No reliable evidence points to their routine use to promote recovery following stroke.[52]

Premature ejaculation[edit | edit source]

SSRIs are effective for the treatment of premature ejaculation. Taking SSRIs on a chronic, daily basis is more effective than taking them prior to sexual activity.[53] The increased efficacy of treatment when taking SSRIs on a daily basis is consistent with clinical observations that the therapeutic effects of SSRIs generally take several weeks to emerge.[54] Sexual dysfunction ranging from decreased libido to anorgasmia is usually considered to be a significantly distressing side effect which may lead to noncompliance in patients receiving SSRIs.[55] However, for those suffering from premature ejaculation, this very same side effect becomes the desired effect.

Other uses[edit | edit source]

SSRIs such as sertraline have been found to be effective in decreasing anger.[56]

Side effects[edit | edit source]

Side effects vary among the individual drugs of this class and may include:

- increased risk of bone fractures[57]

- akathisia[58][59][60][61]

- suicidal ideation (thoughts of suicide) (see below)

Bruxism[edit | edit source]

SSRI and SNRI antidepressants may cause jaw pain/jaw spasm reversible syndrome (although it is not common). Buspirone appears to be successful in treating bruxism on SSRI/SNRI induced jaw clenching.[62][63][64][65]

Sexual dysfunction[edit | edit source]

SSRIs can cause various types of sexual dysfunction such as anorgasmia, erectile dysfunction, diminished libido, genital numbness, and sexual anhedonia (pleasureless orgasm).[66] Sexual problems are common with SSRIs.[67] Poor sexual function is also one of the most common reasons people stop the medication.[68]

In some cases, symptoms of sexual dysfunction may persist after discontinuation of SSRIs.[66][69][70]: 14 [71][72] This combination of symptoms is sometimes referred to as Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction (PSSD).[73][74] On the 11th of June 2019 the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee of the European Medicines Agency concluded that a possible relationship exists between SSRI use and persistent sexual dysfunction after cessation of use. The committee concluded that a warning should be added to the label of SSRIs and SNRIs regarding this possible risk.[75][76]

The mechanism by which SSRIs may cause sexual side effects is not well understood as of 2021[update]. The range of possible mechanisms includes (1) nonspecific neurological effects (e.g., sedation) that globally impair behavior including sexual function; (2) specific effects on brain systems mediating sexual function; (3) specific effects on peripheral tissues and organs, such as the penis, that mediate sexual function; and (4) direct or indirect effects on hormones mediating sexual function.[77] Management strategies include: for erectile dysfunction the addition of a PDE5 inhibitor such as sildenafil; for decreased libido, possibly adding or switching to bupropion; and for overall sexual dysfunction, switching to nefazodone.[78]

A number of non-SSRI drugs are not associated with sexual side effects (such as bupropion, mirtazapine, tianeptine, agomelatine and moclobemide[79][80]).

Several studies have suggested that SSRIs may adversely affect semen quality.[81]

While trazodone (an antidepressant with alpha adrenergic receptor blockade) is a notorious cause of priapism, cases of priapism have also been reported with certain SSRIs (e.g. fluoxetine, citalopram).[82]

Violence[edit | edit source]

Researcher David Healy and others have reviewed available data, concluding that SSRIs increase violent acts, in adults and children, both on therapy and during withdrawal.[83] This view is also shared by some patient activist groups.[84]

Heart[edit | edit source]

SSRIs do not appear to affect the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) in those without a previous diagnosis of CHD.[85] A large cohort study suggested no substantial increase in the risk of cardiac malformations attributable to SSRI usage during the first trimester of pregnancy.[86] A number of large studies of people without known pre-existing heart disease have reported no EKG changes related to SSRI use.[87] The recommended maximum daily dose of citalopram and escitalopram was reduced due to concerns with QT prolongation.[88][89][90] In overdose, fluoxetine has been reported to cause sinus tachycardia, myocardial infarction, junctional rhythms and trigeminy. Some authors have suggested electrocardiographic monitoring in patients with severe pre-existing cardiovascular disease who are taking SSRIs.[91]

Bleeding[edit | edit source]

SSRIs interact with anticoagulants, like warfarin, and antiplatelet drugs, like aspirin.[92][93][94][95] This includes an increased risk of GI bleeding, and post operative bleeding.[92] The relative risk of intracranial bleeding is increased, but the absolute risk is very low.[96] SSRIs are known to cause platelet dysfunction.[97][98] This risk is greater in those who are also on anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents and NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), as well as with the co-existence of underlying diseases such as cirrhosis of the liver or liver failure.[99][100]

Fracture risk[edit | edit source]

Evidence from longitudinal, cross-sectional, and prospective cohort studies suggests an association between SSRI usage at therapeutic doses and a decrease in bone mineral density, as well as increased fracture risk,[101][102][103][104] a relationship that appears to persist even with adjuvant bisphosphonate therapy.[105] However, because the relationship between SSRIs and fractures is based on observational data as opposed to prospective trials, the phenomenon is not definitively causal.[106] There also appears to be an increase in fracture-inducing falls with SSRI use, suggesting the need for increased attention to fall risk in elderly patients using the medication.[106] The loss of bone density does not appear to occur in younger patients taking SSRIs.[107]

Discontinuation syndrome[edit | edit source]

Serotonin reuptake inhibitors should not be abruptly discontinued after extended therapy, and whenever possible, should be tapered over several weeks to minimize discontinuation-related symptoms which may include nausea, headache, dizziness, chills, body aches, paresthesias, insomnia, and brain zaps. Paroxetine may produce discontinuation-related symptoms at a greater rate than other SSRIs, though qualitatively similar effects have been reported for all SSRIs.[108][109] Discontinuation effects appear to be less for fluoxetine, perhaps owing to its long half-life and the natural tapering effect associated with its slow clearance from the body. One strategy for minimizing SSRI discontinuation symptoms is to switch the patient to fluoxetine and then taper and discontinue the fluoxetine.[108]

Serotonin syndrome[edit | edit source]

Serotonin syndrome is typically caused by the use of two or more serotonergic drugs, including SSRIs.[110] Serotonin syndrome is a condition that can range from mild (most common) to deadly. Mild symptoms may consist of increased heart rate, shivering, sweating, dilated pupils, myoclonus (intermittent jerking or twitching), as well as overresponsive reflexes.[111] Concomitant use of an SSRI or selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor for depression with a triptan for migraine does not appear to heighten the risk of the serotonin syndrome.[112] The prognosis in a hospital setting is generally good if correctly diagnosed. Treatment consists of discontinuing any serotonergic drugs as well as supportive care to manage agitation and hyperthermia, usually with benzodiazepines.[113]

Suicide[edit | edit source]

Children and adolescents[edit | edit source]

Meta analyses of short duration randomized clinical trials have found that SSRI use is related to a higher risk of suicidal behavior in children and adolescents.[114][115][116] For instance, a 2004 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) analysis of clinical trials on children with major depressive disorder found statistically significant increases of the risks of "possible suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior" by about 80%, and of agitation and hostility by about 130%.[117] According to the FDA, the heightened risk of suicidality is within the first one to two months of treatment.[118][119][120] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) places the excess risk in the "early stages of treatment".[121] The European Psychiatric Association places the excess risk in the first two weeks of treatment and, based on a combination of epidemiological, prospective cohort, medical claims, and randomized clinical trial data, concludes that a protective effect dominates after this early period. A 2014 Cochrane review found that at six to nine months, suicidal ideation remained higher in children treated with antidepressants compared to those treated with psychological therapy.[120]

A recent comparison of aggression and hostility occurring during treatment with fluoxetine to placebo in children and adolescents found that no significant difference between the fluoxetine group and a placebo group.[122] There is also evidence that higher rates of SSRI prescriptions are associated with lower rates of suicide in children, though since the evidence is correlational, the true nature of the relationship is unclear.[123]

In 2004, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the United Kingdom judged fluoxetine (Prozac) to be the only antidepressant that offered a favorable risk-benefit ratio in children with depression, though it was also associated with a slight increase in the risk of self-harm and suicidal ideation.[124] Only two SSRIs are licensed for use with children in the UK, sertraline (Zoloft) and fluvoxamine (Luvox), and only for the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder. Fluoxetine is not licensed for this use.[125]

Adults[edit | edit source]

It is unclear whether SSRIs affect the risk of suicidal behavior in adults.

- A 2005 meta-analysis of drug company data found no evidence that SSRIs increased the risk of suicide; however, important protective or hazardous effects could not be excluded.[126]

- A 2005 review observed that suicide attempts are increased in those who use SSRIs as compared to placebo and compared to therapeutic interventions other than tricyclic antidepressants. No difference risk of suicide attempts was detected between SSRIs versus tricyclic antidepressants.[127]

- On the other hand, a 2006 review suggests that the widespread use of antidepressants in the new "SSRI-era" appears to have led to a highly significant decline in suicide rates in most countries with traditionally high baseline suicide rates. The decline is particularly striking for women who, compared with men, seek more help for depression. Recent clinical data on large samples in the US too have revealed a protective effect of antidepressant against suicide.[128]

- A 2006 meta-analysis of random controlled trials suggests that SSRIs increase suicide ideation compared with placebo. However, the observational studies suggest that SSRIs did not increase suicide risk more than older antidepressants. The researchers stated that if SSRIs increase suicide risk in some patients, the number of additional deaths is very small because ecological studies have generally found that suicide mortality has declined (or at least not increased) as SSRI use has increased.[129]

- An additional meta-analysis by the FDA in 2006 found an age-related effect of SSRI's. Among adults younger than 25 years, results indicated that there was a higher risk for suicidal behavior. For adults between 25 and 64, the effect appears neutral on suicidal behavior but possibly protective for suicidal behavior for adults between the ages of 25 and 64. For adults older than 64, SSRI's seem to reduce the risk of both suicidal behavior.[114]

- In 2016 a study criticized the effects of the FDA Black Box suicide warning inclusion in the prescription. The authors discussed the suicide rates might increase also as a consequence of the warning.[130]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding[edit | edit source]

SSRI use in pregnancy has been associated with a variety of risks with varying degrees of proof of causation. As depression is independently associated with negative pregnancy outcomes, determining the extent to which observed associations between antidepressant use and specific adverse outcomes reflects a causative relationship has been difficult in some cases.[131] In other cases, the attribution of adverse outcomes to antidepressant exposure seems fairly clear.

SSRI use in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion of about 1.7-fold.[132][133] Use is also associated preterm birth.[134]

A systematic review of the risk of major birth defects in antidepressant-exposed pregnancies found a small increase (3% to 24%) in the risk of major malformations and a risk of cardiovascular birth defects that did not differ from non-exposed pregnancies.[135] [136] Other studies have found an increased risk of cardiovascular birth defects among depressed mothers not undergoing SSRI treatment, suggesting the possibility of ascertainment bias, e.g. that worried mothers may pursue more aggressive testing of their infants.[137] Another study found no increase in cardiovascular birth defects and a 27% increased risk of major malformations in SSRI exposed pregnancies.[133]

The FDA issued a statement on July 19, 2006 stating nursing mothers on SSRIs must discuss treatment with their physicians. However, the medical literature on the safety of SSRIs has determined that some SSRIs like Sertraline and Paroxetine are considered safe for breastfeeding.[138][139][140]

Neonatal abstinence syndrome[edit | edit source]

Several studies have documented neonatal abstinence syndrome, a syndrome of neurological, gastrointestinal, autonomic, endocrine and/or respiratory symptoms among a large minority of infants with intrauterine exposure. These syndromes are short-lived, but insufficient long-term data is available to determine whether there are long-term effects.[141][142]

Persistent pulmonary hypertension[edit | edit source]

Persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN) is a serious and life-threatening, but very rare, lung condition that occurs soon after birth of the newborn. Newborn babies with PPHN have high pressure in their lung blood vessels and are not able to get enough oxygen into their bloodstream. About 1 to 2 babies per 1000 babies born in the U.S. develop PPHN shortly after birth, and often they need intensive medical care. It is associated with about a 25% risk of significant long-term neurological deficits.[143] A 2014 meta analysis found no increased risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension associated with exposure to SSRI's in early pregnancy and a slight increase in risk associates with exposure late in pregnancy; "an estimated 286 to 351 women would need to be treated with an SSRI in late pregnancy to result in an average of one additional case of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn.".[144] A review published in 2012 reached conclusions very similar to those of the 2014 study.[145]

Neuropsychiatric effects in offspring[edit | edit source]

According to a 2015 review available data found that "some signal exists suggesting that antenatal exposure to SSRIs may increase the risk of ASDs (autism spectrum disorders)"[146] even though a large cohort study published in 2013[147] and a cohort study using data from Finland's national register between the years 1996 and 2010 and published in 2016 found no significant association between SSRI use and autism in offspring.[148] The 2016 Finland study also found no association with ADHD, but did find an association with increased rates of depression diagnoses in early adolescence.[148]

Overdose[edit | edit source]

SSRIs appear safer in overdose when compared with traditional antidepressants, such as the tricyclic antidepressants. This relative safety is supported both by case series and studies of deaths per numbers of prescriptions.[149] However, case reports of SSRI poisoning have indicated that severe toxicity can occur[150] and deaths have been reported following massive single ingestions,[151] although this is exceedingly uncommon when compared to the tricyclic antidepressants.[149]

Because of the wide therapeutic index of the SSRIs, most patients will have mild or no symptoms following moderate overdoses. The most commonly reported severe effect following SSRI overdose is serotonin syndrome; serotonin toxicity is usually associated with very high overdoses or multiple drug ingestion.[152] Other reported significant effects include coma, seizures, and cardiac toxicity.[149]

Bipolar switch[edit | edit source]

In adults and children suffering from bipolar disorder, SSRIs may cause a bipolar switch from depression into hypomania/mania. When taken with mood stabilizers, the risk of switching is not increased, however when taking SSRI's as a monotherapy, the risk of switching may be twice or three times that of the average.[153][154] The changes are not often easy to detect and require monitoring by family and mental health professionals.[155] This switch might happen even with no prior (hypo)manic episodes and might therefore not be foreseen by the psychiatrist.

Interactions[edit | edit source]

The following drugs may precipitate serotonin syndrome in people on SSRIs:[156][157]

- Linezolid

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) including moclobemide, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, selegiline and methylene blue

- Lithium

- Sibutramine

- MDMA (ecstasy)

- Dextromethorphan

- Tramadol

- 5-HTP

- Pethidine/meperidine

- St. John's wort

- Yohimbe

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Buspirone

- Triptan

- Mirtazapine

Painkillers of the NSAIDs drug family may interfere and reduce efficiency of SSRIs and may compound the increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeds caused by SSRI use.[93][95][158] NSAIDs include:

There are a number of potential pharmacokinetic interactions between the various individual SSRIs and other medications. Most of these arise from the fact that every SSRI has the ability to inhibit certain P450 cytochromes.[159][160][161]

| Drug name | CYP1A2 | CYP2C9 | CYP2C19 | CYP2D6 | CYP3A4 | CYP2B6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Escitalopram | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| Fluoxetine | + | ++ | +/++ | +++ | + | + |

| Fluvoxamine | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | + | + |

| Paroxetine | + | + | + | +++ | + | +++ |

| Sertraline | + | + | +/++ | + | + | + |

Legend:

0 — no inhibition

+ — mild inhibition

++ — moderate inhibition

+++ — strong inhibition

The CYP2D6 enzyme is entirely responsible for the metabolism of hydrocodone, codeine[162] and dihydrocodeine to their active metabolites (hydromorphone, morphine, and dihydromorphine, respectively), which in turn undergo phase 2 glucuronidation. These opioids (and to a lesser extent oxycodone, tramadol, and methadone) have interaction potential with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.[163][164] The concomitant use of some SSRIs (paroxetine and fluoxetine) with codeine may decrease the plasma concentration of active metabolite morphine, which may result in reduced analgesic efficacy.[165][166]

Another important interaction of certain SSRIs involves paroxetine, a potent inhibitor of CYP2D6, and tamoxifen, an agent used commonly in the treatment and prevention of breast cancer. Tamoxifen is a prodrug that is metabolised by the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme system, especially CYP2D6, to its active metabolites. Concomitant use of paroxetine and tamoxifen in women with breast cancer is associated with a higher risk of death, as much as a 91 percent in women who used it the longest.[167]

Mechanism of action[edit | edit source]

Serotonin reuptake inhibition[edit | edit source]

In the brain, messages are passed from a nerve cell to another via a chemical synapse, a small gap between the cells. The presynaptic cell that sends the information releases neurotransmitters including serotonin into that gap. The neurotransmitters are then recognized by receptors on the surface of the recipient postsynaptic cell, which upon this stimulation, in turn, relays the signal. About 10% of the neurotransmitters are lost in this process; the other 90% are released from the receptors and taken up again by monoamine transporters into the sending presynaptic cell, a process called reuptake.

SSRIs inhibit the reuptake of serotonin. As a result, the serotonin stays in the synaptic gap longer than it normally would, and may repeatedly stimulate the receptors of the recipient cell. In the short run, this leads to an increase in signaling across synapses in which serotonin serves as the primary neurotransmitter. On chronic dosing, the increased occupancy of post-synaptic serotonin receptors signals the pre-synaptic neuron to synthesize and release less serotonin. Serotonin levels within the synapse drop, then rise again, ultimately leading to downregulation of post-synaptic serotonin receptors.[168] Other, indirect effects may include increased norepinephrine output, increased neuronal cyclic AMP levels, and increased levels of regulatory factors such as BDNF and CREB.[169] Owing to the lack of a widely accepted comprehensive theory of the biology of mood disorders, there is no widely accepted theory of how these changes lead to the mood-elevating and anti-anxiety effects of SSRIs.[citation needed]

Sigma receptor ligands[edit | edit source]

| Medication | SERT | σ1 | σ2 | σ1 / SERT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | 1.16 | 292–404 | Agonist | 5,410 | 252–348 |

| Escitalopram | 2.5 | 288 | Agonist | ND | ND |

| Fluoxetine | 0.81 | 191–240 | Agonist | 16,100 | 296–365 |

| Fluvoxamine | 2.2 | 17–36 | Agonist | 8,439 | 7.7–16.4 |

| Paroxetine | 0.13 | ≥1,893 | ND | 22,870 | ≥14,562 |

| Sertraline | 0.29 | 32–57 | Antagonist | 5,297 | 110–197 |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||||

In addition to their actions as reuptake inhibitors of serotonin, some SSRIs are also, coincidentally, ligands of the sigma receptors.[170][171] Fluvoxamine is an agonist of the σ1 receptor, while sertraline is an antagonist of the σ1 receptor, and paroxetine does not significantly interact with the σ1 receptor.[170][171] None of the SSRIs have significant affinity for the σ2 receptor, and the SNRIs, unlike the SSRIs, do not interact with either of the sigma receptors.[170][171] Fluvoxamine has by far the strongest activity of the SSRIs at the σ1 receptor.[170][171] High occupancy of the σ1 receptor by clinical dosages of fluvoxamine has been observed in the human brain in positron emission tomography (PET) research.[170][171] It is thought that agonism of the σ1 receptor by fluvoxamine may have beneficial effects on cognition.[170][171] In contrast to fluvoxamine, the relevance of the σ1 receptor in the actions of the other SSRIs is uncertain and questionable due to their very low affinity for the receptor relative to the SERT.[172]

Anti-inflammatory effects[edit | edit source]

The role of inflammation and the immune system in depression has been extensively studied. The evidence supporting this link has been shown in numerous studies over the past ten years. Nationwide studies and meta-analyses of smaller cohort studies have uncovered a correlation between pre-existing inflammatory conditions such as type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), or hepatitis, and an increased risk of depression. Data also shows that using pro-inflammatory agents in the treatment of diseases like melanoma can lead to depression. Several meta-analytical studies have found increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in depressed patients.[173] This link has led scientists to investigate the effects of antidepressants on the immune system.

SSRIs were originally invented with the goal of increasing levels of available serotonin in the extracellular spaces. However, the delayed response between when patients first begin SSRI treatment to when they see effects has led scientists to believe that other molecules are involved in the efficacy of these drugs.[174] To investigate the apparent anti-inflammatory effects of SSRIs, both Kohler et al. and Więdłocha et al. conducted meta-analyses which have shown that after antidepressant treatment the levels of cytokines associated with inflammation are decreased.[175][176] A large cohort study conducted by researchers in the Netherlands investigated the association between depressive disorders, symptoms, and antidepressants with inflammation. The study showed decreased levels of interleukin (IL)-6, a cytokine that has proinflammatory effects, in patients taking SSRIs compared to non-medicated patients.[177]

Treatment with SSRIs has shown reduced production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, and interferon (IFN)-γ, which leads to a decrease in inflammation levels and subsequently a decrease in the activation level of the immune response.[178] These inflammatory cytokines have been shown to activate microglia which are specialized macrophages that reside in the brain. Macrophages are a subset of immune cells responsible for host defense in the innate immune system. Macrophages can release cytokines and other chemicals to cause an inflammatory response. Peripheral inflammation can induce an inflammatory response in microglia and can cause neuroinflammation. SSRIs inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production which leads to less activation of microglia and peripheral macrophages. SSRIs not only inhibit the production of these proinflammatory cytokines, they also have been shown to upregulate anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10. Taken together, this reduces the overall inflammatory immune response.[178][179]

In addition to affecting cytokine production, there is evidence that treatment with SSRIs has effects on the proliferation and viability of immune system cells involved in both innate and adaptive immunity. Evidence shows that SSRIs can inhibit proliferation in T-cells, which are important cells for adaptive immunity and can induce inflammation. SSRIs can also induce apoptosis, programmed cell death, in T-cells. The full mechanism of action for the anti-inflammatory effects of SSRIs is not fully known. However, there is evidence for various pathways to have a hand in the mechanism. One such possible mechanism is the increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) as a result of interference with activation of protein kinase A (PKA), a cAMP dependent protein. Other possible pathways include interference with calcium ion channels, or inducing cell death pathways like MAPK[180] and Notch signaling pathway.[181]

The anti-inflammatory effects of SSRIs have prompted studies of the efficacy of SSRIs in the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, RA, inflammatory bowel diseases, and septic shock. These studies have been performed in animal models but have shown consistent immune regulatory effects. Fluoxetine, an SSRI, has also shown efficacy in animal models of graft vs. host disease.[180] SSRIs have also been used successfully as pain relievers in patients undergoing oncology treatment. The effectiveness of this has been hypothesized to be at least in part due to the anti-inflammatory effects of SSRIs.[179]

Pharmacogenetics[edit | edit source]

Large bodies of research are devoted to using genetic markers to predict whether patients will respond to SSRIs or have side effects that will cause their discontinuation, although these tests are not yet ready for widespread clinical use.[182]

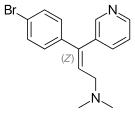

Versus TCAs[edit | edit source]

SSRIs are described as 'selective' because they affect only the reuptake pumps responsible for serotonin, as opposed to earlier antidepressants, which affect other monoamine neurotransmitters as well, and as a result, SSRIs have fewer side effects.

There appears to be no significant difference in effectiveness between SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants, which were the most commonly used class of antidepressants before the development of SSRIs.[183] However, SSRIs have the important advantage that their toxic dose is high, and, therefore, they are much more difficult to use as a means to commit suicide. Further, they have fewer and milder side effects. Tricyclic antidepressants also have a higher risk of serious cardiovascular side effects, which SSRIs lack.

SSRIs act on signal pathways such as cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) on the postsynaptic neuronal cell, which leads to the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF enhances the growth and survival of cortical neurons and synapses.[169]

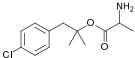

History[edit | edit source]

Fluoxetine was introduced in 1987 and was the first major SSRI to be marketed.

Society and culture[edit | edit source]

Controversy[edit | edit source]

A study examining publication of results from FDA-evaluated antidepressants concluded that those with favorable results were much more likely to be published than those with negative results.[184] Furthermore, an investigation of 185 meta-analyses on antidepressants found that 79% of them had authors affiliated in some way to pharmaceutical companies and that they were also reluctant to reporting caveats for antidepressants.[185]

David Healy has argued that warning signs were available for many years prior to regulatory authorities moving to put warnings on antidepressant labels that they might cause suicidal thoughts.[186] At the time these warnings were added, others argued that the evidence for harm remained unpersuasive[187][188] and others continued to do so after the warnings were added.[189][190]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Barlow DH, durand VM (2009). "Chapter 7: Mood Disorders and Suicide". Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach (Fifth ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-495-09556-9. OCLC 192055408.

- ↑ The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances (PDF). WHO. 2011. p. 37. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-12. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Hitchings, Andrew; Lonsdale, Dagan; Burrage, Daniel; Baker, Emma (2019). The Top 100 Drugs: Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7020-7442-4. Archived from the original on 2021-05-22. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ↑ "List of Common SSRIs + Uses & Side Effects". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ↑ "How Antidepressants Block Serotonin Transport". ALS. 12 July 2016. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ↑ Jakobsen JC, Katakam KK, Schou A, Hellmuth SG, Stallknecht SE, Leth-Møller K, Iversen M, Banke MB, Petersen IJ, Klingenberg SL, Krogh J, Ebert SE, Timm A, Lindschou J, Gluud C (February 2017). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus placebo in patients with major depressive disorder. A systematic review with meta-analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 17 (1): 58. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1173-2. PMC 5299662. PMID 28178949.

- ↑ Hetrick, SE; McKenzie, JE; Cox, GR; Simmons, MB; Merry, SN (14 November 2012). "Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 11: CD004851. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004851.pub3. PMID 23152227.

- ↑ Stein, Dan J.; Kupfer, David J.; Schatzberg, Alan F. (2007). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Mood Disorders. American Psychiatric Pub. p. PT485. ISBN 978-1-58562-716-5. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ↑ Preskorn SH, Ross R, Stanga CY (2004). "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors". In Sheldon H. Preskorn, Hohn P. Feighner, Christina Y. Stanga, Ruth Ross (eds.). Antidepressants: Past, Present and Future. Berlin: Springer. pp. 241–62. ISBN 978-3-540-43054-4. Archived from the original on 2021-07-26. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Ghaffari Darab, M; Hedayati, A; Khorasani, E; Bayati, M; Keshavarz, K (November 2020). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depression disorder treatment: an umbrella review on systematic reviews". International journal of psychiatry in clinical practice. 24 (4): 357–370. doi:10.1080/13651501.2020.1782433. PMID 32667275.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Shelton RC (2009). "Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors: similarities and differences". Primary Psychiatry. 16 (4): 25. Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Montgomery, Stuart A. (July 2008). "Tolerability of serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants". CNS Spectrums. 13 (7 Suppl 11): 27–33. doi:10.1017/s1092852900028297. ISSN 1092-8529. PMID 18622372.

- ↑ Waller DG, Sampson T (4 June 2017). Medical Pharmacology and Therapeutics E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-0-7020-7190-4. Archived from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ Kornstein SG, Clayton AH (5 May 2010). Women's Mental Health, An Issue of Psychiatric Clinics – E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 389–. ISBN 978-1-4557-0061-5. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ Bruno A, Morabito P, Spina E, Muscatello MR (2016). "The Role of Levomilnacipran in the Management of Major Depressive Disorder: A Comprehensive Review". Current Neuropharmacology. 14 (2): 191–9. doi:10.2174/1570159x14666151117122458. PMC 4825949. PMID 26572745.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Mandrioli R, Protti M, Mercolini L (2018). "New-Generation, non-SSRI Antidepressants: Therapeutic Drug Monitoring and Pharmacological Interactions. Part 1: SNRIs, SMSs, SARIs". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 24 (7): 772–792. doi:10.2174/0929867324666170712165042. PMID 28707591.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Ayd FJ (2000). Lexicon of Psychiatry, Neurology, and the Neurosciences. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 581–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5. Archived from the original on 2020-08-19. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Progress in Drug Research. Birkhäuser. 6 December 2012. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-3-0348-8391-7. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Moltzen EK, Bang-Andersen B (2006). "Serotonin reuptake inhibitors: the corner stone in treatment of depression for half a century—a medicinal chemistry survey". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (17): 1801–23. doi:10.2174/156802606778249810. PMID 17017959.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Haddad PM (2000). "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Past, Present and Future. Edited by S. Clare Standford, R.G. Landes Company, Austin, Texas, USA, 1999". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 15 (6): 471. doi:10.1002/1099-1077(200008)15:6<471::AID-HUP211>3.0.CO;2-4. ISBN 1-57059-649-2.

- ↑ Medford N, Sierra M, Baker D, David AS (2005). "Understanding and treating depersonalisation disorder". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 11 (2): 92–100. doi:10.1192/apt.11.2.92.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (October 2009). "Depression Quick Reference Guide" (PDF). NICE clinical guidelines 90 and 91. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2013.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJAMA2010 - ↑ 24.0 24.1 Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT (February 2008). "Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". PLOS Medicine. 5 (2): e45. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050045. PMC 2253608. PMID 18303940.

- ↑ Horder J, Matthews P, Waldmann R (June 2010). "Placebo, Prozac and PLoS: significant lessons for psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (10): 1277–88. doi:10.1177/0269881110372544. hdl:2108/54719. PMID 20571143. S2CID 10323933.

- ↑ Fountoulakis KN, Möller HJ (August 2010). "Efficacy of antidepressants: a re-analysis and re-interpretation of the Kirsch data". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 14 (3): 405–412. doi:10.1017/S1461145710000957. PMID 20800012.

- ↑ Depression: The NICE Guideline on the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (PDF) (Updated ed.). RCPsych Publications. 2010. ISBN 978-1-904671-85-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-19. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Gibbons RD, Hur K, Brown CH, Davis JM, Mann JJ (June 2012). "Benefits from antidepressants: synthesis of 6-week patient-level outcomes from double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trials of fluoxetine and venlafaxine". Archives of General Psychiatry. 69 (6): 572–9. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2044. PMC 3371295. PMID 22393205.

- ↑ Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J (January 2010). "Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis". JAMA. 303 (1): 47–53. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1943. PMC 3712503. PMID 20051569.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:0 - ↑ Hieronymus F, Lisinski A, Näslund J, Eriksson E (2018). "Multiple possible inaccuracies cast doubt on a recent report suggesting selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors to be toxic and ineffective". Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 30 (5): 244–250. doi:10.1017/neu.2017.23. PMID 28718394.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, Leucht S, Ruhe HG, Turner EH, Higgins JP, Egger M, Takeshima N, Hayasaka Y, Imai H, Shinohara K, Tajika A, Ioannidis JP, Geddes JR (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ↑ Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, Thaler K, Lux L, Van Noord M, Mager U, Thieda P, Gaynes BN, Wilkins T, Strobelberger M, Lloyd S, Reichenpfader U, Lohr KN (December 2011). "Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 155 (11): 772–85. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00009. PMID 22147715.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Hetrick SE, McKenzie JE, Cox GR, Simmons MB, Merry SN (Nov 14, 2012). "Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD004851. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004851.pub3. hdl:11343/59246. PMID 23152227.

- ↑ Furukawa, TA; Salanti, G; Cowen, PJ; Leucht, S; Cipriani, A (May 2020). "No benefit from flexible titration above minimum licensed dose in prescribing antidepressants for major depression: systematic review". Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 141 (5): 401–409. doi:10.1111/acps.13145. PMID 31891415.

- ↑ Canton, John; Scott, Kate M; Glue, Paul (2012). "Optimal treatment of social phobia: systematic review and meta-analysis". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 8: 203–215. doi:10.2147/NDT.S23317. ISSN 1176-6328. PMC 3363138. PMID 22665997.

- ↑ Alexander, Walter (January 2012). "Pharmacotherapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder In Combat Veterans". Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 37 (1): 32–38. ISSN 1052-1372. PMC 3278188. PMID 22346334.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-21. Retrieved 2013-02-20.

- ↑ Katzman, Martin A; Bleau, Pierre; Blier, Pierre; Chokka, Pratap; Kjernisted, Kevin; Van Ameringen, Michael (2014-07-02). "Canadian clinical practice guidelines for the management of anxiety, posttraumatic stress and obsessive-compulsive disorders". BMC Psychiatry. 14 (Suppl 1): S1. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-14-S1-S1. ISSN 1471-244X. PMC 4120194. PMID 25081580.

- ↑ "Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Core interventions in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder" (PDF). November 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Arroll B, Elley CR, Fishman T, Goodyear-Smith FA, Kenealy T, Blashki G, et al. (July 2009). Arroll B (ed.). "Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009 (3): CD007954. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007954. PMID 19588448. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Busko M (28 February 2008). "Review Finds SSRIs Modestly Effective in Short-Term Treatment of OCD". Medscape. Archived from the original on April 13, 2013.

- ↑ Fineberg NA, Brown A, Reghunandanan S, Pampaloni I (2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder" (PDF). The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (8): 1173–91. doi:10.1017/S1461145711001829. PMID 22226028. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ "Sertraline prescribing information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-16. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ↑ "Paroxetine prescribing information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-02-19. Retrieved 2015-01-30.

- ↑ Batelaan, Neeltje M.; Van Balkom, Anton J. L. M.; Stein, Dan J. (2012-04-01). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of panic disorder: an update". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (3): 403–415. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000800. ISSN 1461-1457. PMID 21733234. Archived from the original on 2018-03-11. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Asnis, G. M.; Hameedi, F. A.; Goddard, A. W.; Potkin, S. G.; Black, D.; Jameel, M.; Desagani, K.; Woods, S. W. (2001-08-05). "Fluvoxamine in the treatment of panic disorder: a multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in outpatients". Psychiatry Research. 103 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00265-7. ISSN 0165-1781. PMID 11472786. S2CID 40412606.

- ↑ Bighelli, I.; Castellazzi, M.; Cipriani, A.; Girlanda, F.; Guaiana, G.; Koesters, M.; Turrini, G.; Furukawa, T. A.; Barbui, C. (2018). "Antidepressants for panic disorder in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4: CD010676. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010676.pub2. PMC 6494573. PMID 29620793. Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2020-03-14.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 "Eating disorders in over 8s: management" (PDF). Clinical guideline [CG9]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). January 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-03-27. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders". National Guideline Clearinghouse. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25.

- ↑ Flament MF, Bissada H, Spettigue W (March 2012). "Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of eating disorders". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 15 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1017/S1461145711000381. PMID 21414249.

- ↑ Legg, Lynn A.; Tilney, Russel; Hsieh, Cheng-Fang; Wu, Simiao; Lundström, Erik; Rudberg, Ann-Sofie; Kutlubaev, Mansur A.; Dennis, Martin; Soleimani, Babak; Barugh, Amanda; Hackett, Maree L. (26 November 2019). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for stroke recovery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009286.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6953348. PMID 31769878.

- ↑ Waldinger MD (November 2007). "Premature ejaculation: state of the art". The Urologic Clinics of North America. 34 (4): 591–9, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.011. PMID 17983899.

- ↑ Machado-Vieira; Baumann; Wheeler-Castillo; Latov; Henter; Salvadore; Zarate (January 2010). "The Timing of Antidepressant Effects: A Comparison of Diverse Pharmacological and Somatic Treatments". Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 3 (1): 19–41. doi:10.3390/ph3010019. PMID 27713241.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Higgins; Nash; Lynch (September 2010). "Antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: impact, effects, and treatment". Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2: 141–150. doi:10.2147/DHPS.S7634. PMID 21701626.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Romero-Martínez Á, Murciano-Martí S, Moya-Albiol L (May 2019). "Is Sertraline a Good Pharmacological Strategy to Control Anger? Results of a Systematic Review". Behav Sci (Basel). 9 (5): 57. doi:10.3390/bs9050057. PMC 6562745. PMID 31126061.

- ↑ Wu Q, Bencaz AF, Hentz JG, Crowell MD (January 2012). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies". Osteoporosis International. 23 (1): 365–75. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1778-8. PMID 21904950. S2CID 37138272.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Stahl SM, Lonnen AJ (2011). "The Mechanism of Drug-induced Akathsia". CNS Spectrums. PMID 21406165.

- ↑ Lane RM (1998). "SSRI-induced extrapyramidal side-effects and akathisia: implications for treatment". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 12 (2): 192–214. doi:10.1177/026988119801200212. PMID 9694033. S2CID 20944428.

- ↑ Koliscak LP, Makela EH (2009). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced akathisia". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 49 (2): e28–36, quiz e37–8. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08083. PMID 19289334.

- ↑ Leo RJ (1996). "Movement disorders associated with the serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 57 (10): 449–54. doi:10.4088/jcp.v57n1002. PMID 8909330.

- ↑ Garrett, A. R.; Hawley, J. S. (2018). "SSRI-associated bruxism: A systematic review of published case reports". Neurology. Clinical Practice. 8 (2): 135–141. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000433. ISSN 2163-0402. PMC 5914744. PMID 29708207.

- ↑ Prisco, V.; Iannaccone, T.; Di Grezia, G. (2017-04-01). "Use of buspirone in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sleep bruxism". European Psychiatry. Abstract of the 25th European Congress of Psychiatry. 41: S855. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1701. ISSN 0924-9338.

- ↑ Albayrak, Yakup; Ekinci, Okan (2011). "Duloxetine-induced nocturnal bruxism resolved by buspirone: case report". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 34 (4): 137–138. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3182227736. ISSN 1537-162X. PMID 21768799.

- ↑ Prisco, V.; Iannaccone, T.; Di Grezia, G. (2017-04-01). "Use of buspirone in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sleep bruxism". European Psychiatry. Abstract of the 25th European Congress of Psychiatry. 41: S855. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1701. ISSN 0924-9338. Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Bahrick AS (2008). "Persistence of Sexual Dysfunction Side Effects after Discontinuation of Antidepressant Medications: Emerging Evidence". The Open Psychology Journal. 1: 42–50. doi:10.2174/1874350100801010042.

- ↑ Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Bullemor-Day P, Lubin J, Chukwujekwu C, Hawton K (May 2013). "Strategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medication". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5 (5): CD003382. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003382.pub3. PMID 23728643. Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Kennedy SH, Rizvi S (April 2009). "Sexual dysfunction, depression, and the impact of antidepressants". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 29 (2): 157–64. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e31819c76e9. PMID 19512977. S2CID 739831.

- ↑ Waldinger MD (2015). "Psychiatric disorders and sexual dysfunction". Neurology of Sexual and Bladder Disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 130. pp. 469–89. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63247-0.00027-4. ISBN 978-0-444-63247-0. PMID 26003261.

- ↑ "Prozac Highlights of Prescribing Information" (PDF). Eli Lilly and Company. 24 March 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ Reisman Y (October 2017). "Sexual Consequences of Post-SSRI Syndrome". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 5 (4): 429–433. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.05.002. PMID 28642048.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ↑ Healy, David (2020). "Post-SSRI sexual dysfunction & other enduring sexual dysfunctions". Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 29: 1–2. doi:10.1017/S2045796019000519. Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Bahrick, AS (2006). "Post SSRI sexual dysfunction". American society for the advancement of pharmacotherapy. Tablet 7.3: 2–3.

- ↑ Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) (11 June 2019). "New product information wording – Extracts from PRAC recommendations on signals" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. EMA/PRAC/265221/2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ "Minutes of PRAC meeting of 13-16 May 2019: Signal of persistent sexual dysfunction after drug withdrawal" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 14 June 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2021. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ↑ Gitlin MJ (September 1994). "Psychotropic medications and their effects on sexual function: diagnosis, biology, and treatment approaches". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 55 (9): 406–13. PMID 7929021.

- ↑ Balon R (2006). "SSRI-Associated Sexual Dysfunction". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (9): 1504–9, quiz 1664. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1504. PMID 16946173.

- ↑ Clayton AH (2003). "Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction: A Potentially Avoidable Therapeutic Challenge". Primary Psychiatry. 10 (1): 55–61. Archived from the original on 2020-06-04. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ↑ Kanaly KA, Berman JR (December 2002). "Sexual side effects of SSRI medications: potential treatment strategies for SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction". Current Women's Health Reports. 2 (6): 409–16. PMID 12429073.

- ↑ Koyuncu H, Serefoglu EC, Ozdemir AT, Hellstrom WJ (September 2012). "Deleterious effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment on semen parameters in patients with lifelong premature ejaculation". International Journal of Impotence Research. 24 (5): 171–3. doi:10.1038/ijir.2012.12. PMID 22573230.

- ↑ Scherzer, Nikolas D.; Reddy, Amit G.; Le, Tan V.; Chernobylsky, David; Hellstrom, Wayne J.G. (April 2019). "Unintended Consequences: A Review of Pharmacologically-Induced Priapism". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 7 (2): 283–292. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.09.002. PMID 30503727.

- ↑ Healy D, Herxheimer A, Menkes DB (September 2006). "Antidepressants and violence: problems at the interface of medicine and law". PLOS Medicine. 3 (9): e372. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030372. PMC 1564177. PMID 16968128.

- ↑ Breggin PR, Breggin GR (1995). Talking Back to Prozac. Macmillan Publishers. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-312-95606-6.

- ↑ Oh SW, Kim J, Myung SK, Hwang SS, Yoon DH (Mar 20, 2014). "Antidepressant Use and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 78 (4): 727–37. doi:10.1111/bcp.12383. PMC 4239967. PMID 24646010.

- ↑ Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, Cohen LS, Holmes LB, Franklin JM, Mogun H, Levin R, Kowal M, Setoguchi S, Hernández-Díaz S (2014). "Antidepressant Use in Pregnancy and the Risk of Cardiac Defects". New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (25): 2397–2407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828. PMC 4062924. PMID 24941178.

- ↑ Goldberg RJ (1998). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: infrequent medical adverse effects". Archives of Family Medicine. 7 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1001/archfami.7.1.78. PMID 9443704.

- ↑ FDA (December 2018). "FDA Drug Safety". FDA. Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Citalopram and escitalopram: QT interval prolongation—new maximum daily dose restrictions (including in elderly patients), contraindications, and warnings Archived 2013-03-06 at the Wayback Machine. From Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Article date: December 2011

- ↑ "Clinical and ECG Effects of Escitalopram Overdose" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2012-09-23.

- ↑ Pacher P, Ungvari Z, Nanasi PP, Furst S, Kecskemeti V (Jun 1999). "Speculations on difference between tricyclic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants on their cardiac effects. Is there any?". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (6): 469–80. PMID 10213794.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Weinrieb RM, Auriacombe M, Lynch KG, Lewis JD (March 2005). "Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and the risk of bleeding". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 4 (2): 337–44. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.2.337. PMID 15794724. S2CID 46551382.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Taylor D, Carol P, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470979693.

- ↑ Andrade C, Sandarsh S, Chethan KB, Nagesh KS (December 2010). "Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants and Abnormal Bleeding: A Review for Clinicians and a Reconsideration of Mechanisms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1565–1575. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. PMID 21190637.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 de Abajo FJ, García-Rodríguez LA (July 2008). "Risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine therapy: interaction with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and effect of acid-suppressing agents". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (7): 795–803. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.795. PMID 18606952.

- ↑ Hackam DG, Mrkobrada M (2012). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and brain hemorrhage: a meta-analysis". Neurology. 79 (18): 1862–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318271f848. PMID 23077009. S2CID 11941911. Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Serebruany VL (February 2006). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and increased bleeding risk: are we missing something?". The American Journal of Medicine. 119 (2): 113–6. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.044. PMID 16443409.

- ↑ Halperin D, Reber G (2007). "Influence of antidepressants on hemostasis". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 9 (1): 47–59. PMC 3181838. PMID 17506225.

- ↑ Andrade C, Sandarsh S, Chethan KB, Nagesh KS (2010). "Serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanisms". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (12): 1565–75. doi:10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. PMID 21190637.

- ↑ de Abajo FJ (2011). "Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on platelet function: mechanisms, clinical outcomes and implications for use in elderly patients". Drugs & Aging. 28 (5): 345–67. doi:10.2165/11589340-000000000-00000. PMID 21542658.

- ↑ Eom CS, Lee HK, Ye S, Park SM, Cho KH (May 2012). "Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 27 (5): 1186–95. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1554. PMID 22258738.

- ↑ Bruyère O, Reginster JY (February 2015). "Osteoporosis in patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a focus on fracture outcome". Endocrine. 48 (1): 65–8. doi:10.1007/s12020-014-0357-0. PMID 25091520. S2CID 32286954. Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Hant FN, Bolster MB (April 2016). "Drugs that may harm bone: Mitigating the risk". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 83 (4): 281–8. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.15066. PMID 27055202.

- ↑ Fernandes BS, Hodge JM, Pasco JA, Berk M, Williams LJ (January 2016). "Effects of Depression and Serotonergic Antidepressants on Bone: Mechanisms and Implications for the Treatment of Depression". Drugs & Aging. 33 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0323-4. PMID 26547857. S2CID 7648524.

- ↑ Nyandege AN, Slattum PW, Harpe SE (April 2015). "Risk of fracture and the concomitant use of bisphosphonates with osteoporosis-inducing medications". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 49 (4): 437–47. doi:10.1177/1060028015569594. PMID 25667198. S2CID 20622369.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Warden SJ, Fuchs RK (October 2016). "Do Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) Cause Fractures?". Current Osteoporosis Reports. 14 (5): 211–8. doi:10.1007/s11914-016-0322-3. PMID 27495351. S2CID 5610316.

- ↑ Winterhalder L, Eser P, Widmer J, Villiger PM, Aeberli D (December 2012). "Changes in volumetric BMD of radius and tibia upon antidepressant drug administration in young depressive patients". Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions. 12 (4): 224–9. PMID 23196265.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, Rosenbaum JF, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Van Rhoads RS (October 2010). Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (PDF) (third ed.). American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 978-0-89042-338-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2021-04-15.[page needed]

- ↑ Renoir T (2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant treatment discontinuation syndrome: a review of the clinical evidence and the possible mechanisms involved". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 4: 45. doi:10.3389/fphar.2013.00045. PMC 3627130. PMID 23596418.

- ↑ Volpi-Abadie J, Kaye AM, Kaye AD (2013). "Serotonin syndrome". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (4): 533–40. PMC 3865832. PMID 24358002.

- ↑ Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–20. doi:10.1056/nejmra041867. PMID 15784664. S2CID 37959124. Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Orlova Y, Rizzoli P, Loder E (May 2018). "Association of Coprescription of Triptan Antimigraine Drugs and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor or Selective Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants With Serotonin Syndrome". JAMA Neurology. 75 (5): 566–572. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.5144. PMC 5885255. PMID 29482205.

- ↑ Ferri, Fred F. (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1154–1155. ISBN 9780323448383. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Stone MB, Jones ML (2006-11-17). "Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and suicidal behavior in adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ↑ Levenson M, Holland C (2006-11-17). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2007-09-22.

- ↑ Olfson M, Marcus SC, Shaffer D (August 2006). "Antidepressant drug therapy and suicide in severely depressed children and adults: A case-control study". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (8): 865–72. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.865. PMID 16894062.

- ↑ Hammad TA (2004-08-16). "Review and evaluation of clinical data. Relationship between psychiatric drugs and pediatric suicidal behavior" (PDF). FDA. pp. 42, 115. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ "Antidepressant Use in Children, Adolescents, and Adults". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017.

- ↑ "FDA Medication Guide for Antidepressants". Archived from the original on 2014-08-18. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Cox GR, Callahan P, Churchill R, Hunot V, Merry SN, Parker AG, Hetrick SE (November 2014). "Psychological therapies versus antidepressant medication, alone and in combination for depression in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD008324. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008324.pub3. PMID 25433518.

- ↑ "www.nice.org.uk" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-18. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ Tauscher-Wisniewski S, Nilsson M, Caldwell C, Plewes J, Allen AJ (October 2007). "Meta-analysis of aggression and/or hostility-related events in children and adolescents treated with fluoxetine compared with placebo". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 17 (5): 713–8. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.0138. PMID 17979590.

- ↑ Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ (November 2006). "The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (11): 1898–904. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.11.1898. PMID 17074941. S2CID 2390497. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-04-15.

- ↑ "Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants" (PDF). MHRA. 2004-12-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ↑ "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents including a summary of available safety and efficacy data". MHRA. 2005-09-29. Archived from the original on 2008-08-02. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ↑ Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D (February 2005). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's safety review". BMJ. 330 (7488): 385. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.385. PMC 549105. PMID 15718537.

- ↑ Fergusson D, Doucette S, Glass KC, Shapiro S, Healy D, Hebert P, Hutton B (February 2005). "Association between suicide attempts and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: systematic review of randomised controlled trials". BMJ. 330 (7488): 396. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.396. PMC 549110. PMID 15718539.

- ↑ Rihmer Z, Akiskal H (August 2006). "Do antidepressants t(h)reat(en) depressives? Toward a clinically judicious formulation of the antidepressant-suicidality FDA advisory in light of declining national suicide statistics from many countries". Journal of Affective Disorders. 94 (1–3): 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.04.003. PMID 16712945.

- ↑ Hall WD, Lucke J (2006). "How have the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants affected suicide mortality?". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 40 (11–12): 941–50. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2006.01917.x. PMID 17054562.

- ↑ Martínez-Aguayo JC, Arancibia M, Concha S, Madrid E (2016). "Ten years after the FDA black box warning for antidepressant drugs: A critical narrative review". Archives of Clinical Psychiatry. 43 (3): 60–66. doi:10.1590/0101-60830000000086.

- ↑ Malm H (December 2012). "Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and infant outcome". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 34 (6): 607–14. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31826d07ea. PMID 23042258. S2CID 22875385.

- ↑ Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M (2006). "Pregnancy outcomes following exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of clinical trials". Reproductive Toxicology. 22 (4): 571–575. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.03.019. PMID 16720091.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Hendoiee N, Abdollahi M (2012). "Increasing the risk of spontaneous abortion and major malformations in newborns following use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy: A systematic review and updated meta-analysis". Daru. 20 (1): 75. doi:10.1186/2008-2231-20-75. PMC 3556001. PMID 23351929.

- ↑ Eke AC, Saccone G, Berghella V (November 2016). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BJOG. 123 (12): 1900–1907. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14144. PMID 27239775.

- ↑ Einarson TR, Kennedy D, Einarson A (2012). "Do findings differ across research design? The case of antidepressant use in pregnancy and malformations". Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology. 19 (2): e334–48. PMID 22946124.

- ↑ Riggin L, Frankel Z, Moretti M, Pupco A, Koren G (April 2013). "The fetal safety of fluoxetine: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 35 (4): 362–9. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30965-8. PMID 23660045.

- ↑ Koren G, Nordeng HM (February 2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and malformations: case closed?". Seminars in Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 18 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/j.siny.2012.10.004. PMID 23228547.

- ↑ "Breastfeeding Update: SDCBC's quarterly newsletter". Breastfeeding.org. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ↑ "Using Antidepressants in Breastfeeding Mothers". kellymom.com. Archived from the original on 2010-09-23. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ↑ Gentile S, Rossi A, Bellantuono C (2007). "SSRIs during breastfeeding: spotlight on milk-to-plasma ratio". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 10 (2): 39–51. doi:10.1007/s00737-007-0173-0. PMID 17294355. S2CID 757921.

- ↑ Fenger-Grøn J, Thomsen M, Andersen KS, Nielsen RG (September 2011). "Paediatric outcomes following intrauterine exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a systematic review". Danish Medical Bulletin. 58 (9): A4303. PMID 21893008.