Typhoid Fever

From Nwe

From Nwe |

Rose colored spots on the chest of a person with typhoid fever |

|

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | A01.0 |

| ICD-O: | |

| ICD-9 | 002 |

| OMIM | [1] |

| MedlinePlus | [2] |

| eMedicine | / |

| DiseasesDB | [3] |

Typhoid fever (or enteric fever) is an illness caused by the bacterium Salmonella typhi (Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi, which is historically elevated to species status as S. typhi) and less commonly by Salmonella paratyphi. Common worldwide, typhoid fever is transmitted by the feco-oral route, which incorporates ingestion of food or water contaminated with feces from an infected person. Transmission involving infected urine is possible, but much less common (Giannella 1996).

Once ingested, the bacteria are ingested by macrophages (cells in the body that engulf the bacteria and attempt to destroy it). The bacteria then reaches the lymphatic organs, such as the liver, spleen, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and Peyer's patches in the intestine. It resists destruction and multiplies, releasing itself into the blood stream, and consequently spreads throughout the body. Eventually, the bacteria is excreted in bile from the gall bladder and reaches the intestines to be eliminated with waste.

There is a significant element of personal and social responsibility evident with respect to the transmission of typhoid fever. Although insect vectors can play a role in transferring the bacteria to food, typhoid fever is most commonly transmitted through poor hygiene and public sanitation. Washing one's hands after visiting the lavatory or before handling food are important in controlling this disease. The value of personal responsibility is reflected in the use of the phrase "Typhoid Mary," a generic term (derived from the actions of an actual person) for a carrier of a dangerous disease who is a threat to the public because of refusal to take appropriate precautions.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), typhoid fever is common in most areas of the world except in industrialized regions, such as the western Europe, the United States, Canada, Japan, and Australia. The CDC advises travelers to the developing world to take precautions, noting that travelers to Asia, Africa, and Latin America have been especially at risk.

Symptoms

Once ingested, the average incubation period of typhoid fever varies from 1 to 14 days, depending on the virulence of the organism as well as the species. During this period, the infected patient may suffer from a variety of symptoms, such as altered bowel habits, headaches, generalized weakness, and abdominal pain.

Once the bacteremia worsens, the onset of disease manifests with the following clinical features:

- a high fever from 39°C to 40°C (103°F to 104°F) that rises slowly

- chills

- bouts of sweating

- bradycardia (slow heart rate) relative to the fever

- diarrhea, commonly described as "pea-soup" stools

- lack of appetite

- constipation

- abdominal pain

- cough

- skin symptoms

- in some cases, a rash of flat, rose-colored spots called "rose spots," which manifest on the trunk and abdomen; these salmon colored spots are known to blanch on pressure and usually disappear 2-5 days after the onset of the disease

- children often vomit and have diarrhea

- weak and rapid pulse

- weakness

- headaches

- myalgia (muscle pain)—not to be confused with the more severe muscle pain in Dengue fever, known as "Breakbone fever"

- in some cases, loss of hair resulting from the prolonged high fever

- delusions, confusion, and parkinson's-like symptoms have also been noted

- extreme symptoms such as intestinal perforation or hemorrhage usually occur after 3-4 weeks of untreated disease and can be fatal

One to four percent of patients become chronic carriers of the disease and continue to excrete bacteria for greater than 1 year following infection. During this time, they are mostly asymptomatic and continue to excrete the bacteria through bile. This subset of patients is usually known to have gall bladder abnormalities, such as the presence of gallstones.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of typhoid fever is made by blood, bone marrow, or stool cultures, and with the Widal test (demonstration of salmonella antibodies against antigens O-somatic, H-flagellar, Vi-surface virulence). In epidemics and less wealthy countries, after excluding malaria, dysentery, and pneumonia, a therapeutic trial with chloramphenicol is generally undertaken while awaiting the results of Widal test and blood cultures (Ryan and Ray 2004).

Treatment

Typhoid fever can be fatal. When untreated, typhoid fever persists for three weeks to a month. Death occurs in between 10 percent and 30 percent of untreated cases.

Antibiotics, such as ampicillin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and ceftriaxone have commonly been used to treat typhoid fever in developed countries. Prompt treatment of the disease with antibiotics reduces the case-fatality rate to approximately 1 percent. Usage of Ofloxacin along with Lactobacillus acidophilus is also recommended.

Vaccines for typhoid fever are available and are advised for persons traveling in regions where the disease is common (especially Asia, Africa, and Latin America). Typhim Vi, which is an intramuscular killed-bacteria vaccination, and Vivotif, a live, oral bacteria vaccination, both protect against typhoid fever. Neither vaccine is 100 percent effective against typhoid fever and neither protects against unrelated typhus. A third acetone-inactivated parenteral vaccine preparation is available for select groups, such as military.

Resistance

Resistance to antibiotics like ampicillin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and streptomycin is now common, and these agents have not been used as first line treatment now for almost 20 years. Typhoid fever that is resistant to these agents is known as multidrug-resistant typhoid (MDR typhoid).

Ciprofloxacin resistance is an increasing problem, especially in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Many centers are therefore moving away from using ciprofloxacin as first line for treating suspected typhoid originating in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand, or Vietnam. For these patients, the recommended first line treatment is ceftriaxone.

There is a separate problem with laboratory testing for reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. Current recommendations are that isolates should be tested simultaneously against ciprofloxacin (CIP) and against nalidixic acid (NAL), and that isolates that are sensitive to both CIP and NAL should be reported as "sensitive to ciprofloxacin," but that isolates testing sensitive to CIP but not to NAL should be reported as "reduced sensitivity to ciprofloxacin." However, an analysis of 271 isolates showed that around 18 percent of isolates with a reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (Mean inhibitory concentration 0.125–1.0 mg/l) would not be picked up by this method (Cooke et al. 2006). It is not certain how this problem can be solved, since most laboratories around the world (including the West) are dependent on disc testing and cannot test for MICs.

Transmission

While flying insects feeding on feces may occasionally transfer the bacteria to food being prepared for consumption, typhoid fever is most commonly transmitted through poor hygiene habits and poor public sanitation conditions. Public education campaigns encouraging people to wash their hands after using the lavatory and before handling food are an important component in controlling spread of this disease.

A person may become an asymptomatic (suffering no symptoms) carrier of typhoid fever, but capable of infecting others. According to the Centers for Disease Control, approximately 5 percent of people who contract typhoid continue to carry the disease even after they recover.

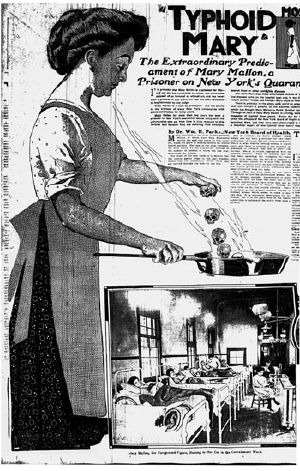

The most notorious carrier of typhoid fever, but by no means the most destructive, was Mary Mallon, an Irish immigrant also known as Typhoid Mary. In 1907, she became the first American carrier to be identified and traced. Some believe she was the source of infection for several hundred people, and is closely associated with fifty cases and five deaths.

While working as a cook in the New York City area between 1900 and 1907, Mary Mallon is said to have infected 22 people with the disease, of whom one died. Mary was a cook in a house in Mamaroneck, New York, for less than two weeks in the year 1900 when the residents came down with typhoid. She moved to Manhattan in 1901, and members of that family developed fevers and diarrhea, and the laundress died. She then went to work for a lawyer, until seven of the eight household members developed typhoid. Mary spent months helping to care for the people she apparently made sick, but her care further spread the disease through the household. In 1904, she took a position on Long Island. Within two weeks, four of ten family members were hospitalized with typhoid. She changed employment again, and three more households were infected. Often, the disease was transmitted by a signature dessert she prepared: Peaches and ice cream. Public health authorities told Mary to give up working as a cook or have her gall bladder removed. Mary quit her job, but returned later under a false name in 1915, infecting 25 people while working as a cook at New York's Sloan Hospital; two of those infected died. She was then detained and quarantined. She died of a stroke after 26 years in quarantine. An autopsy found evidence of live typhoid bacteria in her gallbladder. Today, a Typhoid Mary is a generic term for a carrier of a dangerous disease who is a danger to the public because he or she refuses to take appropriate precautions.

Heterozygous advantage

It is thought that Cystic Fibrosis may have risen to its present levels (1 in 1600 in the United Kingdom) due to the heterozygous advantage that it confers against typhoid fever. Heterozygous refers to the dissimilar pairs of genes a person can have for any hereditary characteristic. The CFTR protein is present in both the lungs and the intestinal epithelium, and the mutant cystic fibrosis form of the CFTR protein prevents entry of the typhoid bacterium into the body through the intestinal epithelium.

History

The fall of Athens and typhoid fever, 430- 426 B.C.E.: A devastating plague, which some believe to have been typhoid fever, killed one third of the population of Athens, including their leader Pericles. The balance of power shifted from Athens to Sparta, ending the Golden Age of Pericles that had marked Athenian dominance in the ancient world. Ancient historian Thucydides also contracted the disease, but survived to write about the plague. His writings are the primary source on this outbreak.

The cause of the plague has long been disputed, with modern academics and medical scientists considering epidemic typhus the most likely cause. However, a 2006 study detected DNA sequences similar to those of the bacterium responsible for typhoid fever (Papagrigorakis 2006). Other scientists have disputed the findings, citing serious methodologic flaws in the dental pulp-derived DNA study. In addition, as the disease is most commonly transmitted through poor hygiene habits and poor public sanitation conditions, it is an unlikely cause of a widespread plague, emerging in Africa and moving into the Greek city states, as reported by Thucydides.

Chicago, 1860-1900: Chicago typhoid fever mortality rate averaged 65 per 100,000 people a year from 1860 to 1900. The worst year was 1891. As the incidence rate of the disease was about ten times the death rate, in 1891 more than 1.5 percent of the population of Chicago was affected by typhoid.[1]

Vaccine, 1897: Edward Almwroth Wright developed the effective vaccine against typhoid fever in 1897.

Famous typhoid fever victims

Among famous people who have succumbed to the disease are included:

- Alexander the Great (military commander who conquered most of the world known to ancient Greeks)

- Pericles (leader in Athens during the city's Golden Age)

- Archduke Karl Ludwig of Austria (son's assassination in Sarajevo precipitated the Austrian declaration of war against Serbia, which triggered World War I)

- William the Conqueror (invaded England, won Battle of Hastings, and was part of Norman Conquest)

- Franz Schubert (an Austrian composer)

- Margaret Breckenridge (highest-ranking Army nurse under Ulysses S. Grant)

- Evangelista Torricelli (an Italian physicist and mathematician, best known for his invention of the barometer)

- Caroline Harrison (United States President Benjamin Harrison's wife)

- Annie Lee (Robert E. Lee's daughter)

- Mary Henrietta Kingsley (an English writer and explorer who greatly influenced European ideas about Africa and African people)

- Herbert Hoover's father and mother

- Katherine McKinley (United States President William McKinley's daughter)

- Wilbur Wright (credited with making the first controlled, powered, heavier-than-air human flight)

- Will Rogers' mother (Rogers was an American comedian, humorist, social commentator, vaudeville performer, and actor)

- Leland Stanford, Jr. (the namesake of Stanford University in the United States)

- William T. Sherman's father (William T. Sherman was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author)

- Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (British prince consort and Queen Victoria's husband)

- William Wallace Lincoln (third son of United States President Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln)

- Tad Lincoln (fourth and youngest son of President Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln)

- Stephen A. Douglas (known as the "Little Giant," was an American politician from the frontier state of Illinois and was one of two Democratic Party nominees for President in 1860)

- Cecile and Jeanne Pasteur (Louis Pasteur's daughters)

- Abigail Adams (United States President John Adams's wife)

- K.B. Hedgewar (founder of Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh)

- General Stonewall Jackson's mother, father, and daughter (Jackson was a Confederate general during the American Civil War)

- John Buford (an Union cavalry officer during the American Civil War, with a prominent role at the start of the Battle of Gettysburg)

- Annie Darwin (Charles Darwin's daughter)

- Joseph Lucas (British industrialist, founded the Lucas company in 1872)

- Ignacio Zaragoza [a general in the Mexican Army, best known for his 1862 victory against the French invading forces in the Battle of Puebla on May 5 (the Cinco de Mayo)]

Notes

- ↑ Water, Typhoid Rates, and the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brusch, J. L. Typhoid Fever. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- Cooke, F. J., J. Wain, and E. J. Threlfall. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella Typhi (letter). British Medical Journal 333(7563) (2006): 353-4.

- Gale, T. Gale's Encyclopedia of Medicine, 1999. ISBN 0787618683

- Giannella, R. A. "Salmonella." In S. Baron et al. (eds.), Baron's Medical Microbiology, 4th ed. University of Texas Medical Branch, 1996. ISBN 0963117211 (via NCBI Bookshelf) Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- Papagrigorakis, M. J., C. Yapijakis, P. N. Synodinos, and E. Baziotopoulou-Valavani. DNA examination of ancient dental pulp incriminates typhoid fever as a probable cause of the Plague of Athens. Int J Infect Dis 10(3) (2006) :206-214.

- Ryan, K. J., and C. G. Ray (eds.). Sherris Medical Microbiology, 4th ed. McGraw Hill, 2004. ISBN 0838585299

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 06:21:44 | 22 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Typhoid_fever | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF