American Civil War

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | American Civil War | |

|---|---|

| |

| Date Begun | April 12, 1861 |

| Date Ended | April 9, 1865 |

| Casualties | Total: 1,032,200 Killed: 203,000 Died from other: 417,000 Wounded: 412,200 |

| United States (Union) | |

| President | Abraham Lincoln |

| Vice-President | Hannibal Hamlin |

| Secretary of State | William Seward |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles |

| Confederate States (Confederacy) | |

| President | Jefferson Davis |

| Vice-President | Alexander Stephans |

| Secretary of State | Robert Toombs |

| Secretary of War | Leroy Pope Walker |

| Secretary of the Navy | Stephan Mallory |

| Military Leaders | |

| Union | Confederate |

The American Civil War, arguably the most traumatic experience in the nation's history, was a major conflict which took place from 1861 to 1865, involving the government of the United States of America against eleven Southern states which seceded from the Union and formed their own government called the Confederate States of America. In proportion to the total population, the Civil War was the most costly war ever fought in American history; more than 650,000 soldiers died in the war, two-thirds from disease and one-third from battle wounds, roughly 2% of the country's population at the time.[1]

The result of simmering tensions directly related to the issue of chattel slavery, the country would split as a result of the emergence of the anti-slavery Republican Party in the North and the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860; the Democratic Party itself would split, with a pro-slavery wing controlling the South, and a northern wing largely indifferent to it. The end of the war would see the South in an economic and physical wreck, followed by an abuse of power by the North during their subsequent decade-long occupation of the Southern states. Incidents of violence and intimidation against blacks ensued throughout the country, and in the 20th century the eugenics movement promoted abortion among blacks which continues to this day.

For the social, political, economic and diplomatic history see American Civil War homefront.

Contents

Names[edit]

The American Civil War has been called by other titles: the War Between the States was popular in the South before the 1970s, as is the informal title The Lost Cause. Officially, the United States government has called it the War of the Rebellion since the government never accepted that the States of the Confederacy had succeeded in leaving the Union. The term "civil war" is most accurate, as it not only involved state against state from a common country, but the splitting of families as well; fathers would take sides against sons, and brother would fight against brother in many battles. In one sad case, Private Wesley Culp of the 2nd Virginia Regiment would die for the Confederacy at the Battle of Gettysburg, killed on his father's farm.[2] Many significant battles of the War were named differently by the North and the South. An early example of this is the First Battle of Bull Run - as named by the Union - where the Confederacy named it the "First Battle of Manassas".

Prelude to war[edit]

Description of the North prior to 1860[edit]

The chief characteristic of the North was its industrialization, which was rapid. Plants to manufacture metal goods sprang up almost as fast as they were invented, and after manufacture they spread quickly. One example was John Deere, who in 1840 was manufacturing a new stainless-steel plow that he had invented barely three years before; by 1848 the plows were selling at the rate of a thousand a year. By 1857, Deere and his partner had expanded with the manufacture of so much farm equipment that the Middle West was made the country's greatest wheat-producing area. Farm equipment also included the first examples of steam-powered plows, and in 1859 there were contests as to who could build and deploy the best plow. One such plow at a contest at Freeport, Illinois caused an official committee to declare the machine could "plow 25 acres a day at 62.5 cents an acre" versus a normal manual charge of $2.50 an acre.[3]

Inventions were not limited to farming. Locomotives, sewing machines, shoe peggers, reapers, augers, turbines, hydraulics, power looms, rotary presses, and more seemingly raced out of factories. Standardization was also an American invention, meaning replacement parts could be made and ordered to replace something broken within the machine instead of replacing the machine itself, as Connecticut's Samuel Colt first demonstrated with his new revolver. And to keep up with the exporting demand, Northern shipyards produced so many ships that they threatened to eclipse their chief rival, Great Britain.[4]

The North was also a melting pot of immigration. Northern cities were crowded and boisterous, and expanding rapidly. New York's population had jumped from 515,000 to 814,000 in the 1850s; Chicago's had gone from its 1837 incorporation with barely more than 4,000 people to over 112,000 by 1860.[5]

Description of the South prior to 1860[edit]

The South was largely agrarian. A Southern boast, "Cotton is king!" became very true by the 1850s, as cotton was grown, harvested, and shipped to market in vast quantities. The number of bales in 1849 was 2 million; by 1859 it had jumped to 5.7 million, amounting to more than half of all American exports and seven-eighths of the total amount of cotton in the world.[6]

Southern politics was controlled by owners of large slave plantations, the small minority of well-to-do planters. They practiced a cultivated chivalry, a code of honor among equals with high levels of dueling. Proud parents, when their son came of age, would present him a handsome set of dueling pistols. The code called for a gallantry towards white women, while it was common to have many children by their black slaves; these children became slaves too.

Cotton was in high demand for textile factories in Europe and profits were high on plantations with 50 or more slaves. Most of the profits went toward purchase of new farmland (because cotton rapidly depletes the fertility of the soil) and more slaves, as well as cheap clothing for the slaves. Relatively little was spent on machinery or on luxury goods. More likely money went to gambling, and racehorses. High prestige occupations included plantation ownership, the law and medicine. Doctors were hired to keep the slaves healthy. There were very few colleges in the region, apart from a few small state schools and military academies. One Mississippi planter, Jefferson Davis, remarked that only in the South "did a gentlemen go to a military academy who did not intend to follow the profession of arms."[7]

But the South had several serious drawbacks. Its population at 1860 was roughly 9 million people, of whom more than 3 million were slaves. There were only 18,000 manufacturing plants of any kind in the South, as opposed to the North's more than 100,000. Of these, only two were capable of producing rolled iron, one which produced gunpowder, and none capable of producing firearms; there were twenty-seven gun manufacturers in Massachusetts alone. More than 70% of all railroad mileage was north of the Ohio River; the South had the remainder.

Slavery[edit]

After the Thirteen Colonies won independence, the British Empire saw slavery cut in half, thereby becoming less profitable.[8] When the sectionalism over slavery was created, the alarmed Thomas Jefferson stated that this is "holding the wolf by the ears." This is why many abolitionists supported secession.

Before the Civil War, the individual states, particularly in the South, shared a belief that each state was sovereign. Sovereignty included jurisdiction over, and the handling of, each state's affairs, which invariably included their own public and private institutions.

The peculiar institution cited more often than anything else in defending states' rights was slavery. Africans had been present as slaves in the American colonies since the early 17th century; over the years the South began to rationalize it less as an evil and more of an economic necessity; so ingrained into the fabric of society had slavery become that Vice President John C. Calhoun was to say in 1838:

| “ | Many in the South once believed that slavery was a moral and political evil. That folly and delusion are gone. We see it now in its true light, and regard it as the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world.[9] | ” |

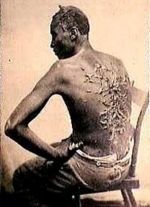

Slaves for the most part were treated brutally. Born in bondage, a slave usually began his first work in the fields at the age of twelve. They would work in the fields from the light of day until, in the words of a Louisiana slave, "until it is too dark to see, and when the moon is full, they often labor until the middle of the night".[10] They were fed and clothed poorly, usually in rags; shoes were uncommon. Disease was rampant, life was short; only four out of 100 lived past age 60. Absolute subservience to whites was enforced. Punishment for infractions was severe, involving stocks, pronged neck collars, and whippings where salt water was used to clear infection, with the resulting pain so excruciating a slave recollecting it wrote "the flesh crawls upon my bones".[11]

Prior to 1793 cotton harvesting was done by hand; slaves harvested, pulled the seed from the boll, and packed it for shipping to market at a rate of 100 bales a week. Then Eli Whitney patented his cotton gin, a machine that did the hard work of separating the seed from the boll, enabling bales of cotton at a rate of over 1000 a week, often more. The result was the number of annual cotton harvests increased to three, which saw a concurrent rise in profits made by plantation owners; the number of slaves needed for the fields and other tasks increased as well, climbing from 300,000 in 1790 to over three million by 1860.

Political machinations and compromises[edit]

The Missouri Compromise (1820) allowed for the entry of Maine into the Union as a free state, and Missouri as a slave state. It was further agreed that slavery was to be excluded from territory north of the 36°30′ parallel, or the remaining western territories. Before admission could be granted to Missouri a clause in the state's constitution provoked controversy: the exclusion of "free Negroes and mulattoes". Under Whig Henry Clay's influence in the U.S. Senate, an act of admission was passed, upon condition that the controversial exclusionary clause should "never be construed to authorize the passage of any law" impairing the privileges and immunities of free citizens. The compromise seemed deliberately ambiguous in that it could be interpreted to indicate that free blacks and mulattoes did not qualify as United States citizens, which would be put to direct test years later with a slave named Dred Scott.[12]

Another crisis arose from the request of the California Territory to be admitted to the Union as a free state; this was complicated by territory acquired in the southwest as a result of the Mexican War of 1848 and whether to extend slavery there. An omnibus bill drafted by Clay called the Compromise of 1850 tried to give satisfaction to the southern states in addition to California's admission: the settlement of the Texas-New Mexico border dispute; the slavery question open for voting via popular sovereignty in the Utah and New Mexico territories as they were organized; the end of slave trading in the District of Columbia; and tough requirements concerning runaway slaves.[13]

All five measures were enacted in September, 1850 as a result of the efforts and support of Democratic senator Stephen A. Douglas and Whig senator Daniel Webster, and were accepted by moderates throughout the country. These measures may have had the effect of postponing Southern secession for another decade, but the seeds of discord were planted; the precedent of popular sovereignty, championed by Douglas as the way for the public to vote whether or not they wanted slavery in their territories, led to the Kansas territory agitating for a similar provision. And the Fugitive Slave Act that was a part of the Compromise was so bitterly condemned that many moderates who had ignored slavery in the past became determined opponents to any extension of the institution into the territories. Many would risk jail rather than turn over runaway slaves to their owners as required by the new laws.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of May 30, 1854, sponsored by Douglas, provided for the territorial organization of Kansas and Nebraska, and used his principle of popular sovereignty. Douglas had written the act in an effort to slow or halt the sectarianism over slavery's extension, but the Kansas-Nebraska Act merely increased the flames, and was attacked by free-soilers and abolitionists as a capitulation to those who supported slavery. The Whig Party, ineffective in preventing it, largely disintegrated, and the Republican Party was born and soon became a viable political organization opposed to territorial expansion of slavery.

On the heels of the act a large number of people left Missouri and sought to influence elections in the Kansas Territory. "Border Ruffians", as they were called, entered Kansas and cast thousands of illegal votes resulting in a pro-slave government that Democratic president Franklin Pierce recognized, and continued doing so even after it was ruled illegitimate by a congressional investigative committee. The territory's actual residents set up their own legislature and created the Topeka Constitution; Pierce declared their endeavors an act of rebellion, and he went so far as to send in Federal troops to break it up.

Bleeding Kansas[edit]

The Border Ruffians also stirred up violence between themselves and the Free-Staters in a bloody affair since known as "Bleeding Kansas", beginning with the burning of a hotel and printing press in Lawrence on May 21, 1856. Several days later an anti-slavery religious fanatic named John Brown and a few followers retaliated against five pro-slavery men, hacking them to death with broadswords. By August thousands of men had formed into pro-slavery armies and marched into Kansas, expecting to force the territory to accept slavery. That same month a small, pitched battle occurred near the city of Osawatomie; 300 pro-slavery soldiers under the command of John W. Reid fought against Brown and 40 men. Brown lost the battle and Osawatomie was looted and burned. A fragile peace led by a new territorial governor would commence only when Brown and his men left the territory.[14]

The day after the hotel in Lawrence was burned, a South Carolina Democrat congressman named Preston Brooks, incensed over an anti-slavery speech given by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, walked onto the Senate floor and viciously beat him with a cane so severely that Sumner took three years to recover, while Brooks' fellow Democrat Laurence M. Keitt used a pistol to keep other politicians at bay to prevent them from stopping the attack.[15] A subsequent attempt to expel Brooks from Congress for his criminal actions failed and he received only a $300 fine and was not imprisoned after being found guilty in a later trial, but Brooks was later publicly humiliated when he no-showed a duel he challenged congressman Anson Burlingame to (which Burlingame goaded Brooks into making in retaliation for the assault on Sumner with a blistering speech in Congress that denounced Brooks as a coward for the attack) and attempted to make flimsy excuses for why he refused to face Burlingame, an expert marksman.

Dred Scott decision[edit]

Dred Scott was owned by an Army physician who was transferred to the state of Wisconsin, a free state, for several years before a transfer to Missouri, a slave state. Scott sued on the grounds that his residence in a free state where slavery was illegal made him free. After a series of unsuccessful lawsuits, Scott appealed to the United States Supreme Court, where in 1856, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney delivered the majority opinion in Dred Scott vs. Sanford:

- Blacks were not entitled to citizenship according to the U.S. Constitution.

- Blacks were not entitled to freedom under the Ordinance of 1797 while within the area of the Northwest Territory, of which Wisconsin was a part.

- The Missouri Compromise of 1820 prohibiting slavery north of Missouri and in free states was voided.

What the Dred Scott decision meant was any slave could be taken anywhere in the Union without fear that the owner of the slave would lose his property; a slave was private property, Taney stated, and according to the Fifth Amendment could not be taken from the owner without due process.[16]

The decision further deteriorated North/South relations, as a stunned North realized that free states had to support the institution of slavery.

Emergence of Lincoln[edit]

The Kansas-Nebraska Act attracted much opposition in the country and led to splitting of the Democrats along the Mason-Dixon line (Douglas in the ensuing years tried desperately to keep it together) as well as the collapse of the Whig Party as an effective political organization. Many former Whigs, whose beliefs included the abolishment of slavery, flocked to the newly formed Republican Party; their number would include a lawyer from Illinois who used the act to jump back into politics after a five-year absence, Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln was nominated for the Senate seat held by Douglas at the Republican State Convention in Springfield on June 16, 1858. The acceptance speech he gave has been called the "House Divided" speech, after the opening lines:

- If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it. We are now far into the fifth year since a policy was initiated with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only not ceased, but has constantly augmented. In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached and passed. "A house divided against itself cannot stand." I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved -- I do not expect the house to fall -- but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new -- North as well as South.[17]

August through October, 1858 saw seven Illinois towns witnessing the Lincoln-Douglas debates; Douglas the national figure defending the choice of voters whether to accept slavery or not, and the little-known Lincoln taking a stand against slavery on political, social, and moral grounds. Douglas never wavered from defending popular sovereignty, and he also played on the voters' fears of black integration. Stating blacks were inferior to whites, he appealed to racists by declaring that the government was "established upon the white basis. It was made by white men, for the benefit of white men."[18] Lincoln on the other hand knew Douglas was in a war of his own with President Franklin Buchanan's administration over acceptance of the Kansas constitution which barred slavery from the state, further alienating Southern Democratic support; the fear was that Douglas would be more appealing to moderate Republicans in the east. Lincoln's strategy therefore was to point out and use the vast difference between the moral indifference to slavery as embodied by Douglas's popular sovereignty, and the moral wrong that slavery actually was as embodied by Republican opposition to it. Douglas was, Lincoln insisted, a man who did not care whether slavery was "voted up or voted down."

Douglas retained his Senate seat, but by a narrow margin. Lincoln, however, won the debates, which thrust him into the national spotlight and put him on the road to the White House.

John Brown at Harpers Ferry[edit]

During the spring of 1858, John Brown held a meeting in Ontario between blacks and whites in which he stated his intentions to form a stronghold in the mountains between Virginia and Maryland for escaped slaves, even going so far as to adopt his own provisional constitution for the United States, which his group adopted. Several prominent Boston abolitionists also gave him financial and moral support.

By summer, 1859, Brown was in a rented farmhouse in Maryland, across the river from the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia; with him was an armed band of sixteen whites and five blacks. On the night of October 16, he raided the armory and took some sixty of the area's leading men as hostages, and hoped that slaves would get word of his forming an "army of emancipation", escape, and fight with him to liberate their fellow slaves. For the next thirty hours he and his men held out against the local militia, but on the following morning a small force of United States Marines led by Army colonel Robert E. Lee quickly broke into the arsenal building, wounding Brown, and killing two of his sons and ten other followers. He was tried for murder, slave insurrection, and treason, and at the end he was convicted and hanged. The day he was to die he spoke no last words, merely handing a note to a guard on which he had written a last, prophetic statement: "I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood."[19]

Ever fearful of a slave insurrection, the South became tougher on its slaves. In Washington, Senator Jefferson Davis assumed, like many others, that the North was behind a conspiracy involving John Brown and others like him, aimed at abolishing slavery. He said in a speech:

- The Government is no longer to intervene in favor of protection for our slaves. We may be robbed of our property, and the General Government will not intervene for our protection. When the Government gets into the hands of the Republican party, the arm of the General Government, we are told, will not be raised for the protection of our slave property. Then intervention in favor of slavery and slave States will no longer be tolerated. We may be invaded, and the Black Republican Government will stand and permit our soil to be violated and our people assailed and raise no arm in our defense. The sovereignty of the State is no longer to be a bar to encroachments upon our rights when the Government gets into Black Republican hands. Then John Brown, and a thousand John Browns, can invade us, and the Government will not protect us.[20]

Many in the North held a different view. Brown was a martyr for abolition. The great orator Frederick Douglas, a freed slave himself who was never afraid to confront the evils of the South's "peculiar institution", perhaps offered the best assessment of Brown:

- His zeal in the cause of freedom was infinitely superior to mine. Mine was as the taper light, his was as the burning sun. Mine was bounded by time. His stretched away to the silent shores of eternity. I could speak for the slave. John Brown could fight for the slave. I could live for the slave. John Brown could die for the slave.[21]

1860 Presidential campaign[edit]

See United States presidential election of 1860

In April, 1860, the Democratic Party held its convention in Charleston, South Carolina, and the first platform placed for a vote is pro-slavery. When it is rejected in the course of voting, delegates from eight states in the South walk out; the remaining delegates are forced to adjourn when they cannot agree on a candidate to represent their party in the White House.[22]

The Republicans hold their convention in Chicago in May, 1860, and Lincoln is nominated on the third ballot; he had to stand as a moderate on the slavery issue in order to gain the nomination. The party's platform insists on leaving slavery alone in the states where it already existed and against the spread of it into the territories.[23]

The Democrats reconvene their convention in Baltimore, Maryland, in June. Stephen Douglas is nominated for the presidency after the Southern delegates walk out again; they would hold their own convention later in Balitmore and nominate Vice-President John C. Breckenridge on a platform calling for the right to slavery.[24]

The election centered on sectionalism and slavery, with each candidate doing little more than fanning the fears of the voters; Douglas would be the only one to travel the country personally, including all Southern states, but the split within his party was too great to make a difference. Lincoln went on to win the election, with 180 electoral votes, and 40% of the popular votes, none of which included a Southern state. Breckenridge placed second, winning 72 electoral votes, and 24% of the popular vote. John C. Bell, a candidate for the Constitutional Union Party (made up of former Whigs and former members of a nativist American party derisively called "Know Nothings"), took the states of Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Last was Douglas, barely managing Missouri, and three out of seven electoral votes from New Jersey. Southern leaders speak openly about secession within days of Lincoln's victory.[25]

The Secession[edit]

Before seceding, the Confederate States issued declarations of secession.[26] By December 1860, both houses of Congress were working on proposals for compromises that would postpone the split they knew was coming. John J. Crittenden of the Senate committee introduced a proposal that would restore the Missouri Compromise by extending the northern boundary line across the continent to the Pacific, as well as preventing Congress or a Constitutional amendment from ever abolishing slavery. The Crittenden Compromise, as well as the others, came down to a vote, but events would prove it was too late. Most of President Buchanan's cabinet, long angered at him (and his predecessor, Democrat Franklin Pierce) for not standing up to Southern demands which were tearing the country apart, walked out in protest; the latest outrage occurred when a delegation from South Carolina arrived at the White House and demanded the removal of Federal troops from the state (Buchanan rejects it). And President-elect Lincoln, although trying to be careful regarding the slavery issue, is insistent that slavery not be expanded into the territories.[27]

On December 20, 1860, the South Carolina government votes to secede from the Union. Within days they begin war preparations, and seize Federal property. By the end of the month Major Robert Anderson spiked the cannon and removed the men stationed at Fort Moultrie in Charleston Harbor; nearby Fort Sumter is considered more defensible, and he places the force there. Aware of Anderson's condition, President Buchanan orders reinforcements sent, and he readied USS Brooklyn for that purpose in Norfolk; she would be replaced days later by General Winfield Scott's preference for a non-Naval supply ship, Star of the West.

On January 6, 1861, Florida troops take the Federal arsenal at Apalachicola. Fort Marion at St. Augustine is seized on the 7th. On the 9th, the Star of the West is fired upon as she neared Charleston, causing her to turn around and head back to Norfolk. That same day public celebrations erupt in Mississippi as the state legislature votes 84-15 to secede.

- January 10, Florida votes 67-2 to secede.

- January 11, Alabama votes 69-31 to secede.

- January 19, Georgia votes 208-89 to secede.

- January 26, Louisiana votes 114-17 to secede.

- February 1, Texas votes 166-7 to secede.

On February 4, a peace convention meets in Washington, headed by former President John Tyler. The 131 members from 21 states (none from the South) work out a last, desperate compromise to save the Union. Speaking to the delegates, Tyler implores that "the eyes of the whole country are turned to this assembly, in expectation and hope." The convention ends in failure.[28]

In Montgomery, Alabama, a provisional congress assembles and draws up a constitution by the end of the week; this document is essentially the United States Constitution, but mildly altered to include provisions for states' rights and protection for slavery:

- The importation of Negroes of the African race from any foreign country other than the slaveholding States or territories of the United States of America, is hereby forbidden; and Congress is required to pass such laws as shall effectually prevent the same. Congress shall also have power to prohibit the introduction of slaves from any State not a member of, or territory not belonging to, this Confederacy.

- The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it. No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law, or law denying or impairing the right of property in Negro slaves, shall be passed.[29]

On February 9, a surprised Jefferson Davis learns he has been elected provisional president of the newly formed Confederate States of America; his vice-president is Alexander Stephens of Georgia. The two are considered moderate enough to please the legislatures of the remaining Southern states which have not yet seceded.

Fort Sumter[edit]

On the 4th of March, 1861, Abraham Lincoln is inaugurated as the nation's 16th president. In his address he reiterated his stance, and what he believed the stance of the nation should be, namely non-interference with slavery where it existed, and preventing slavery to spread in the territories, and above all was his stand to preserve the Union. The substance of what he said was conciliatory, but it also mentioned the obvious:

- "In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The Government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the Government, while I shall have the most solemn one to "preserve, protect, and defend it."[30]

After communications between Fort Sumter and Charleston broke down over quietly surrendering the fort, Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard knew reinforcing the fort was certain, and he may have been aware of a supply ship already on its way from Norfolk. He ordered the fort shelled on April 12, 1861; the honor of firing the first gun went to an ardent secessionist from Virginia, 66-year-old Edmund Ruffin. The fort surrendered on April 14 after 36 hours of bombardment, the single fatality of the engagement was to a Union soldier, killed when a cannon exploded as they were readying a final salute. Major Anderson and his force were immediately paroled, and were allowed to leave on the supply ship a few hours later.

The American Civil War had begun.

Continuing articles[edit]

Sources[edit]

For a guide to web sources see:

- Alice E. Carter and Richard Jensen. The Civil War on the Web: A Guide to the Very Best Sites (2nd ed. 2003) excerpt and text search

For an older short survey that is online and won the Pulitzer prize, see:

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the Civil War, 1861-1865 (1918)

For the best recent survey that is online and won the Pulitzer prize, see:

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988), 900 pages; excerpt and text search; also complete online edition (partial for free, full for a modest fee)

For other recent surveys (not online) see:

- Fellman, Michael et al. This Terrible War: The Civil War and its Aftermath (2nd ed. 2007), 544 pages

- Donald, David et al. The Civil War and Reconstruction (2001); 700 pages

- Time-Life Books The Civil War, vol. 1 (Brother Against Brother), Time Inc, New York (1983), popular history

- Time-Life Books The Civil War, vol. 15 (Gettysburg), Time Inc, New York (1983), popular history

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union (1947–70), the most detailed history by a leading scholar

- Bowman, John S. (editor), The Civil War Almanac World Almanac Publications, New York (1985)

Links[edit]

The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion[edit]

General[edit]

- Library of Congress Civil War map collection

- The Civil War Homepage

- The PBS/Ken Burns documentary

- The History Place

- Civil War at a Glance; US Interior Department

- Shotgun's home of the American Civil War

- US Civil War Center, from Louisiana State University

- Civil War Treasures, from New York Historical Society

- Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln

Prelude to war[edit]

- Full text of the Dred Scott v. Sandford

- Missouri Compromise

- Kansas-Nebraska act

- Compromise of 1850

- Text of the Fugitive Slave Law

- text of speech by Sen. Jefferson Davis, Dec. 8, 1859

- Lecture on John Brown by Frederick Douglas

Emergence of Lincoln[edit]

1860 Presidential Campaign[edit]

Secession[edit]

- Jefferson Davis Inaugural speech, as reported in Harper's Weekly

- text of Licoln's first inaugural speech

- Lincoln's second inaugural speech

- Constitution of the Confederate States

References[edit]

- ↑ https://blogs.ancestry.com/cm/12-stunning-civil-war-facts/

- ↑ TL 15, pp. 154-155

- ↑ Nevins, pg 166-168

- ↑ TL 1, pg 18

- ↑ TL 1, pg 16

- ↑ TL 1, pg 10

- ↑ TL 1, pg 12

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fG98BNpD1s

- ↑ TL 1, pg 40

- ↑ TL 1, pg 48

- ↑ TL 1, pp 49–58

- ↑ http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/Missouri.html

- ↑ http://blueandgraytrail.com/event/Compromise_of_1850

- ↑ http://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/kansas.html

- ↑ Bowman, pg 38

- ↑ http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=US&vol=60&invol=393

- ↑ http://www.historyplace.com/lincoln/divided.htm

- ↑ TL 1, pg 106

- ↑ TL 1, pp.70–89

- ↑ http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/learning_history/brown/public_davis.cfm

- ↑ http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mfd&fileName=22/22002/22002page.db&recNum=9&tempFile=./temp/~ammem_rvc6&filecode=mfd&next_filecode=mfd&prev_filecode=mfd&itemnum=2&ndocs=32

- ↑ Bowman, pg. 40

- ↑ Bowman, pg 40

- ↑ Bowman, pg. 40

- ↑ Bowman, pg 40; Nat. Atlas

- ↑ http://www.civil-war.net/pages/ordinances_secession.asp

- ↑ Bowman, pg. 41

- ↑ Bowman, pg. 45

- ↑ Article 1, section IX

- ↑ https://www.pbs.org/civilwar/war/lincoln_address1.html

Categories: [United States History] [Featured articles] [American Civil War] [Black History] [The South] [Reconstruction]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/28/2023 08:57:58 | 239 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/American_Civil_War | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF