Sushi

From Nwe

From Nwe Prominent in Japanese cuisine, sushi is a food made of vinegared rice balls combined with various toppings or fillings, which are most commonly seafood but can also include meat, vegetables, mushrooms, or eggs. Sushi toppings may be raw, cooked, or marinated.

Sushi as an English word has come to refer to the complete dish (rice together with toppings); this is the sense used in this article. The original term (寿司) sushi (-zushi in some compounds such as makizushi) in the Japanese language refers to the rice, not the fish or other toppings.

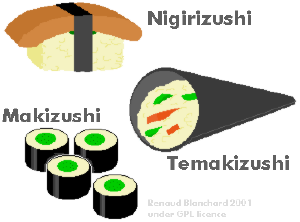

There are various types of sushi. Sushi served rolled in nori (dried sheets of laver, a kind of seaweed) is called maki (rolls). Sushi made with toppings laid onto hand-formed clumps of rice is called nigiri; sushi made with toppings stuffed into a small pouch of fried tofu is called inari; and sushi made with toppings served scattered over a bowl of sushi rice is called chirashi-zushi, or scattered sushi.

Sushi has become increasingly popular in the Western world, and chefs have invented many variations incorporating Western ingredients and sauces together with traditional Japanese ingredients.

History

Origins

The basic idea behind the preparation of sushi is the practice of preserving fish with salt and fermenting with rice, a process that can probably be traced back to seafood-preserving methods used in Southeast Asia, where countries have a long history of rice cultivation. The process originated during the Tang Dynasty in China, though modern Japanese sushi evolved to have little resemblance to this original Chinese food.

The dish internationally known today as "sushi" (nigirizushi; Kanto variety) is a fast food invented by Hanaya Yohei (華屋与兵衛; (1799–1858) at the end of the Edo period in today's Tokyo (Edo). More than one hundred years ago, the people in Tokyo were already in a hurry and needed a food they could eat on the run. The nigirizushi invented by Hanaya was not fermented and could be eaten with the hands (or using a bamboo toothpick). It was a convenient food that could be eaten at a roadside or in a theater.

Etymology

The Japanese name "sushi" is written with kanji (Chinese characters) for ancient Chinese dishes which bear little resemblance to today's sushi.

One of these might have been a salt pickled fish. The first use of "鮨" appeared in the Erya, the oldest Chinese dictionary believed to be written around the third century B.C.E. The definition is literally "Those made with fish (are called) 鮨,” “those made with meat (are called) 醢." "醢" is “a sauce made from minced pork” and "鮨" is “a sauce made from minced fish.” The Chinese character "鮨" is believed to have a much earlier origin, but this is the earliest recorded instance of that character being associated with food. “鮨” was not associated with rice.

In second century C.E., another character used to write "sushi," "鮓," appeared in another Chinese dictionary: "鮓滓也 以塩米醸之加葅 熟而食之也," which translates as "鮓滓is a food where fish is pickled by rice and salt, which is eaten when it is ready." This food is believed to be similar to Narezushi or Funazushi, fish that was fermented for long periods of time in conjunction with rice and was then eaten after removing the rice.

A century later, the meaning of the two characters had become confused and by the time these two characters arrived in Japan, the Chinese themselves did not distinguish between them. The Chinese had stopped using rice as a part of the fermentation process and then stopped eating pickled fish altogether. By the Ming dynasty, "鮨" and "鮓" had disappeared from Chinese cuisine.

Sushi in Japan

The earliest reference to sushi in Japan appeared in 718 C.E. in the set of laws called Yororitsuryo (養老律令). In a list of taxes paid with actual goods instead of currency, it is written down as "雑鮨五斗 (about 64 liters of zakonosushi, or zatsunosushi?)." However, there is no way to know what this "sushi" was or even how it was pronounced.

By the ninth and tenth century C.E., "鮨" and "鮓" are read as "sushi" or "sashi." These "sushi" or "sashi" were similar to today's Narezushi. For almost the next eight hundred years, until the early nineteenth century, sushi slowly changed and Japanese cuisine changed as well. The Japanese started eating three meals a day, rice was boiled instead of steamed, and most important of all rice vinegar was invented. While sushi continued to be produced by fermentation of fish with rice, the time of fermentation was gradually decreased, and the rice used in fermentation began to be eaten along with the fish. In the Muromachi Period (1336–1573), a process to produce oshizushi was gradually developed which eliminated the fermentation process and used vinegar instead. In the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1603), namanari was invented. A 1603 Japanese-Portuguese dictionary has an entry for namanrina sushi, literally “half-made sushi.” The namanari was fermented for a shorter period than the narezushi and possibly marinated with rice vinegar. It still had the distinctive smell of narezushi, which is commonly described as "a cross between bleu cheese, fish, and rice vinegar."

Oshizushi was perfected in Osaka in the early eighteenth century and came to Edo by the middle of eighteenth century. This sushi still required a time to ferment, so stores hung up notices announcing when customers could come to purchase sushi. Sushi was also sold near a park during hanami (cherry blossom viewing) and a theater as a type of bento (lunch box). Inarizushi (sushi made by filling fried tofu skins with rice) was sold along with oshizushi. Makizushi and chirasizushi also became popular during the Edo period.

There were three famous sushi restaurants in Edo, Matsugasushi (松が鮓), Koube (興兵衛), and Kenukisushi (毛抜き), but thousands more were established in a span of barely twenty years at the start of the nineteenth century. Nigirizushi was an instant success and it spread through Edo like wildfire. In the book Morisadamanko (守貞謾稿) published in 1852, the author writes that in a cho (100 meters by 100 meters or 10,000 square meters) section of Edo there were 12 sushi restaurants, but that only one soba restaurant could be found in 12 cho. This means that there were nearly 150 sushi restaurants for every soba restaurant.

These early nigirizushi were not identical to today's varieties. Fish meat was marinated in soy sauce or vinegar or heavily salted so there was no need to dip into soy sauce. Some fish was cooked before it was put onto a sushi. This was partly out of necessity as there were no refrigerators. Each piece was also larger, almost the size of two pieces of today's sushi.

The advent of modern refrigeration allowed sushi made of raw fish to reach more consumers than ever before. The late twentieth century saw sushi gaining in popularity all over the world.

Types of sushi

The common ingredient in all the different kinds of sushi is sushi rice (simply sushi in Japanese). There is a great variety in the choice of fillings and toppings, condiments, and in the manner in which they are put together. The same ingredients may be assembled in various ways, traditional and contemporary.

Nigiri

- Nigiri-zushi (握り寿司, hand-formed sushi). The most typical form of sushi at restaurants, it consists of an oblong mound of sushi rice which is pressed between the palms of the hands, with a speck of wasabi (green horseradish) and a thin slice of a topping (neta) draped over it, possibly bound with a thin band of nori (dried pressed laver, a kind of seaweed). Assembling nigiri-zushi is surprisingly difficult to do well. It is sometimes called Edomaezushi, which reflects its origins in Edo (present-day Tokyo) in the eighteenth century. It is often served in pairs.

- Gunkan-maki (軍艦巻, warship roll). A special type of nigiri-zushi: an oval, hand-formed clump of sushi rice (similar to that of nigiri-zushi) that has a strip of nori wrapped around its perimeter to form a vessel that is filled with the topping. The topping is typically some soft ingredient that requires the confinement of the nori, for example, fish roe, natto (fermented soybeans), or a contemporary macaroni salad. The gunkan-maki was invented at Kyubei Restaurant (established 1932) in Ginza and its invention significantly expanded the repertoire of soft toppings used in sushi.

Maki (roll)

- Makizushi (巻き寿司, rolled sushi). A cylindrical piece, formed with the help of a bamboo mat, called a makisu. Makizushi is generally wrapped in a sheet of nori that encloses the rice and fillings, but can occasionally be found wrapped in a thin omelet. Makizushi is usually cut into six or eight pieces, which constitute an order.

- Futomaki (太巻き, large or “fat” rolls). A large cylindrical piece, with the nori on the outside. Typical futomaki are three or four centimeters in diameter. They are often made with two or three fillings, chosen for their complementary tastes and colors. During the Setsubun festival, it is traditional in Kansai to eat the uncut futomaki in its cylindrical form.

- Hosomaki (細巻き, thin rolls). A small cylindrical piece, with the nori on the outside. Typical hosomaki are about two centimeters thick and two centimeters wide. They are generally made with only one filling.

- Kappamaki, a kind of hosomaki filled with cucumber, is named after the Japanese legendary water imp fond of cucumbers, the Kappa (河童).

- Tekkamaki (鉄火巻き) is a kind of hosomaki filled with tuna. Tekka (鉄火) is a Japanese casino and also describes hot iron, which has a color similar to the red tuna flesh.

- Uramaki (裏巻き, inside-out rolls). A medium-sized cylindrical piece, with two or more fillings. Uramaki differ from other maki because the rice is on the outside and the nori within. The filling is in the center surrounded by a liner of nori, then a layer of rice, and an outer coating of some other ingredient such as roe or toasted sesame seeds. Typically thought of as an invention to suit the American palate, uramaki is not commonly seen in Japan. The California roll is a popular form of uramaki. The increased popularity of sushi in North America, as well as around the world, has resulted in numerous different kinds of uramaki and regional off-shoots being created. Regional types include the B.C. roll (salmon) and Philadelphia roll (cream cheese).

- The dynamite roll includes prawn tempura.

- The rainbow roll features sashimi layered outside the rice.

- The spider roll includes fried soft shell crab.

- Other rolls include scallops, spicy tuna, beef or chicken teriyaki, okra, vegetarian, and cheese. Brown rice and black rice rolls have also appeared.

- Temaki (手巻き, hand rolls). A large cone-shaped piece, with the nori on the outside and the ingredients spilling out the wide end. A typical temaki is about ten centimeters long, and is eaten with the fingers since it is too awkward to pick up with chopsticks.

- Inari-zushi (稲荷寿司, stuffed sushi). A pouch of fried tofu filled usually with just sushi rice. It is named after the Shinto god Inari, whose messenger, the fox, is believed to have a fondness for fried tofu. The pouch is normally fashioned from deep-fried tofu (油揚げ or abura age). Regional variations include pouches made of a thin omelet (帛紗寿司 (hukusa-zushi) or 茶巾寿司 (chakin-zushi)) or dried gourd shavings (干瓢 or kanpyo).

Oshizushi

- Oshizushi (押し寿司, pressed sushi). A block-shaped piece formed using a wooden mold, called an oshibako. The chef lines the bottom of the oshibako with the topping, covers it with sushi rice, and presses the lid of the mold down to create a compact, rectilinear block. The block is removed from the mold and cut into bite-sized pieces.

Chirashi

- Chirashizushi (ちらし寿司, scattered sushi). A bowl of sushi rice with the other ingredients mixed in. Also referred to as barazushi.

- Edomae chirashizushi (Edo-style scattered sushi) Uncooked ingredients artfully arranged on top of the rice in the bowl.

- Gomokuzushi (Kansai-style sushi). Cooked or uncooked ingredients mixed in the body of the rice in the bowl.

Narezushi (old style fermented sushi)

- Narezushi (熟れ寿司, matured sushi) is an older form of sushi. Skinned and gutted fish are stuffed with salt then placed in a wooden barrel, doused with salt again, and weighed down with a heavy tsukemonoishi (pickling stone). They are salted for ten days to a month, and then placed in water for 15 minutes to an hour. They are then placed in another barrel, sandwiched, and layered with cooled steamed rice and fish. Then this mixture is again partially sealed with otosibuta and a pickling stone. As days pass, water seeps out, which must be removed. Six months later, this funazushi can be eaten, and it remains edible for another six months or more.

Ingredients

All sushi has a base of a specially prepared rice, complemented with other ingredients.

Sushi rice

Sushi is made with white, short-grained, Japanese rice mixed with a dressing made of rice vinegar, sugar, salt, kombu (kelp), and sake. It is cooled to body temperature before being used. In some fusion cuisine restaurants, short grain brown rice and wild rice are also used. Sushi rice (sushi-meshi) is prepared with short-grain Japonica rice, which has a consistency that differs from long-grain strains such as Indica. The essential quality is its stickiness. Rice that is too sticky has a mushy texture; if it is not sticky enough, it feels dry. Freshly harvested rice (shinmai) typically has too much water, and requires extra time to drain after washing.

There are regional variations in sushi rice, and of course individual chefs have their individual methods. Most of the variations are in the rice vinegar dressing: the Tokyo version of the dressing commonly uses more salt; in Osaka, the dressing has more sugar.

Sushi rice generally must be used shortly after it is made.

Nori

The seaweed wrappers used in maki and temaki are called nori. This is an algae traditionally cultivated in the harbors of Japan. Originally, the algae was scraped from dock pilings, rolled out into sheets, and dried in the sun in a process similar to making paper. Nori is toasted before being used in food.

Today, the commercial product is farmed, produced, toasted, packaged, and sold in standard-size sheets, about 18 by 21 centimeters in size. Higher quality nori is thick, smooth, shiny, black, and has no holes.

Nori by itself is edible as a snack. Many children love flavored nori, which is coated with teriyaki sauce or toasted with salt and sesame oil. However, this tends to be cheaper, lower-quality nori that is not used for sushi.

Omelette

When making fukusazushi, a paper-thin omelet may replace a sheet of nori as the wrapping. The omelet is traditionally made in a rectangular omelet pan (makiyakinabe) with sugar and rice wine added to the egg, and used to form the pouch for the rice and fillings.

Toppings and fillings

- Fish

- For culinary, sanitary and aesthetic reasons, fish eaten raw must be fresher and of higher quality than fish which is cooked. A professional sushi chef is trained to recognize good fish, which smells clean, has a vivid color, and is free from harmful parasites. Only ocean fish are used raw in sushi; freshwater fish, which are more likely to harbor parasites, are cooked.

- Commonly-used fish are tuna, yellowtail, snapper, conger, eel, mackerel and salmon. The most valued sushi ingredient is toro, the fatty cut of tuna. This comes in varieties ōtoro (often from the bluefin species of tuna) and chutoro, meaning middle toro, implying it is halfway in fattiness between toro and regular red tuna (akami).

- Seafood

- Other seafoods are squid, octopus, shrimp, fish roe, sea urchin (uni), and various kinds of shellfish. Oysters, however, are not typically put in sushi because the taste is not thought to go well with the rice. However, some sushi restaurants in New Orleans are known to have fried oyster rolls and crawfish rolls.

- Vegetables

- Pickled daikon radish (takuan) in shinko maki, various pickled vegetables (tsukemono), fermented soybeans (natto) in nattō maki, avocado in California rolls, cucumber in kappa maki, asparagus, yam, tofu, pickled ume (umeboshi), gourd (kampyō), burdock (gobo), and sweet corn mixed with mayonnaise.

- Red meat

Beef, ham, sausage and horse meat, often lightly cooked.

- Note: It is a common misconception that in Hawaii, fried Spam is a popular local variation of sushi. In reality, Spam musubi differs from sushi in that its rice lacks the vinegar required to classify it as such. Spam musubi is correctly classified as onigiri.

- Other fillings

- Eggs (in the form of a slightly sweet, layered omelet called tamagoyaki), raw quail eggs riding as a gunkan-maki topping.

Condiments

- Soy sauce

- Wasabi: The grated root of the wasabi plant. The best tool to use for grating wasabi is normally considered to be a sharkskin grater or samegawa oroshi. At cheap establishments like kaiten zushi restaurants, bento box grade sushi, and at most restaurants outside of Japan, imitation wasabi (seiyo-wasabi) made of horseradish, sometimes processed in Japan (which allows the use of "Japanese Horseradish" on the label), mustard powder, and FD&C Yellow #5 and Blue #1. Real wasabi (hon-wasabi) is wasabi japonica, a different rhizome from European horseradish. Hon-wasabi has been found to have antimicrobial properties and its consumption with raw fish is believed to help prevent bacterial food poisoning.

- Gari (ginger): Sweet, pickled ginger. Gari is eaten both to cleanse the palette and to aid in the digestive process.

Presentation

In Japan, and increasingly abroad, sushi train (kaiten zushi) restaurants are a popular, cheap way of eating sushi. At these restaurants, the sushi is served on color-coded plates, each color denoting the cost of that piece of sushi. The plates are placed on a conveyor belt or boats floating in a moat which travels along a counter at which the customers are seated. As the belt or boat passes by, the customers can choose what they want to eat. When they have finished, the bill is tallied by counting how many plates of each color have been taken. Some kaiten sushi restaurants in Japan operate on a fixed price system, with each plate, consisting usually of two pieces of sushi, generally costing ¥100.

More traditionally, sushi is served on minimalist Japanese-style, geometric, wood or lacquer plates which are mono- or duo-tone in color, in keeping with the aesthetic qualities of this cuisine. Many small sushi restaurants actually use no plates—the sushi is eaten directly off of the wooden counter, usually with one's hands, despite the historical tradition of eating nigiri with chopsticks.

Modern fusion presentation, particularly in the United States, has given sushi a European sensibility, taking Japanese minimalism and garnishing it with Western touches such as the colorful arrangement of edible ingredients, the use of differently flavored sauces, and the mixing of foreign flavors, highly suggestive of French cuisine, deviating somewhat from the more traditional, austere style of Japanese sushi.

Training of a Sushi Chef

In Japanese culture, becoming a sushi chef requires up to ten years of training. Apprentices may start at the age of fifteen or sixteen, and spend the first two or three years sweeping, washing dishes, doing chores, and learning to wash, boil, and prepare sushi rice. Then they learn how to select and buy the freshest fish and how to prepare it. Finally they are taught the techniques for making and presenting sushi, and can work alongside the master chef. It is an honor to become a sushi chef.

Today there is such a demand for sushi chefs, especially in the West, that many receive only six months of training before going to work as qualified sushi chefs. A good sushi chef is also a creative artist, with a repertoire of decorative sushi and sashimi for special occasions.

Utensils for Preparing Sushi

- Fukin: Kitchen cloth

- Hangiri: Rice barrel

- Japanese kitchen knives (Hocho): Kitchen knives

- Makisu: Bamboo rolling mat

- Ryoribashi: Cooking chopsticks

- Shamoji: Wooden rice paddle

- Makiyakinabe: Rectangular omelet pan

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barber, Kimiko, and Hiroki Takemura. Sushi: Taste and Technique. DK Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-0789489166

- Kawasumi, Ken. The Encyclopedia of Sushi Rolls. Japan Publications Trading Company, 2001. ISBN 978-4889960761

- Shimbo, Hiroko. The Japanese Kitchen. The Harvard Commons Press, 2001. ISBN 978-1558321779

External links

All links retrieved January 12, 2020.

- How to eat Sushi

- Sushi Glossary

- Sushi recipes

- How many calories are in sushi?

- The Sushi FAQ - (The alt.food.sushi Usenet group FAQ)

- How Sushi Works

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 06:40:54 | 46 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Sushi | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF