Indian Rock-Cut Architecture

From Nwe

From Nwe Indian rock-cut architecture has more examples than any other form of rock-cut architecture in the world.[1] Rock-cut architecture defines the practice of creating a structure by carving it out of solid natural rock. The craftsman removes rock not part of the structure until the architectural elements of the excavated interior constitute the only rock left. Indian rock-cut architecture, for the most part, is religious in nature.[2] In India, caves have long been regarded as places of sanctity. Enlarged or entirely man-made caves hold the same sanctity as natural caves. The sanctuary in all Indian religious structures, even free standing ones, retain the same cave-like feeling of sacredness, being small and dark without natural light.

Curiously, Buddhist monks created their cave hermitages near trade routes that crossed northern India during the time of Christ. As wealthy traders became aware of the Buddhist caves, they became benefactors of expansion of the caves, the building of monolithic rock-cut temples, and of free-standing temples. Emperors and rulers also supported the devotional work and participated in the spiritual devotional services. Very likely, traders would use the hermitages for worship on their routes. As Buddhism weakened in the face of a renewed Hinduism during the eighth century C.E., the rock structure maintenance, expansion, and upgrading fell to the Hindus and Jains. Hindu holy men continued building structures out of rock, dedicating temples to Hindu gods like Shiva, until mysteriously they abandoned the temples around the twelfth century C.E. They abandoned the structures so completely that even local peoples lost knowledge of the awesome structures in their midst. Only in the nineteenth century, when British adventurers and explorers found them, did India rediscover the awesome architecture that comprises world treasures.

History

The western Deccan boasts the earliest cave temples, mostly Buddhist shrines and monasteries, dating between 100 B.C.E. and 170 C.E. Wooden structures, destroyed over time while stone endured, probably preceded as well as accompanied the caves. Throughout the history of rock-cut temples, the elements of wooden construction have been retained. Skilled craftsmen learned to mimic timber texture, grain, and structure. The earliest cave temples include the Bhaja Caves, the Karla Caves, the Bedse Caves, the Kanheri Caves and some of the Ajanta Caves. Relics found in those caves suggest an important connection between the religious and the commercial, as Buddhist missionaries often accompanied traders on the busy international trading routes through India. Some of the more sumptuous cave temples, commissioned by wealthy traders, included pillars, arches, and elaborate facades during the time maritime trade boomed between the Roman Empire and southeast Asia.

Although free standing structural temples had been built by the fifth century, the carving of rock-cut cave temples continued in parallel. Later, rock-cut cave architecture became more sophisticated, as in the Ellora Caves, culminating ultimately the monolithic Kailash Temple. After that, rock-cut architecture became almost totally structural in nature (although craftsmen continued carving cave temples until the twelfth century), made from rocks cut into bricks and built as free standing constructions. Kailash provides the last spectacular rock-cut excavated temple.

Early caves

Natural caves used by local inhabitants for a variety of purposes such as shrines and shelters constitute the earliest caves employed by humans. The early caves included overhanging rock decorated with rock-cut art and the use of natural caves during the Mesolithic period (6000 B.C.E.). Their use has continued in some areas into historic times.[3] The Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka, a World Heritage Site, stand on the edge of the Deccan Plateau where deep erosion has left huge sandstone outcrops. The many caves and grottos found there contain primitive tools and decorative rock paintings that reflect the ancient tradition of human interaction with their landscape, an interaction that still continues.[4]

Cave temples

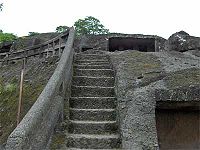

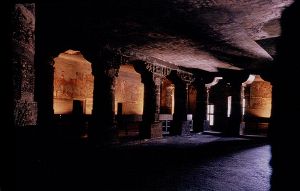

When Buddhist missionaries arrived, they naturally gravitated to caves for use as cave temples and abodes, in accord with their religious ideas of asceticism and the monastic life. The Western Ghats topography with its flat-topped basalt hills, deep ravines, and sharp cliffs, suited well to their natural inclinations. Ajanta constitutes the earliest of the Kanheri Caves, excavated in the first and second centuries B.C.E. Buddhist monks continuously occupied them from 200 B.C.E. to 650 C.E.[5] Buddhist practices encouraged compatibility with trade, monasteries becoming stopovers for inland traders. They provided lodging houses usually located near trade routes. As their mercantile and royal endowments grew, cave interiors became more elaborate with interior walls decorated with paintings and reliefs and intricate carvings. Craftsmen added facades to the exteriors as the interiors became designated for specific uses as monasteries (viharas) and worship halls (chaityas). Over the centuries, simple caves began to resemble three-dimensional buildings, needing formal design and requiring highly skilled artisans and craftsmen to complete. Those artisans had not forgotten their timber roots and imitated the nuances of a wooden structure and the wood grain in working with stone.[6]

Early examples of rock cut architecture include the Buddhist and Jain cave basadi, temples, and monasteries, many with chandrashalas. The aesthetic nature of those religions inclined their followers to live in natural caves and grottoes in the hillsides, away from the cities, and those became enhanced and embellished over time. Although many temples, monasteries and stupas had been destroyed, by contrast cave temples have been extremely well preserved. Situated in out-of-the-way places, hidden from view, the caves have been less visible and therefore less vulnerable to vandalism. The durably of rock, over wood and masonry structures, has contributed to their preservation. Approximately 1200 cave temples still exist, most of them Buddhist. Monks called their residences Viharas and the cave shrines Chaityas. Buddhists used both Viharas and Caityas for congregational worship.[6] The earliest rock-cut garbhagriha, similar to free-standing ones later, had an inner circular chamber with pillars to create a circumambulatory path (pradakshina) around the stupa and an outer rectangular hall for the congregation of the devotees.

The Ajanta Caves in Maharashtra, a World Heritage Site, constitute thirty rock-cut cave Buddhist temples carved into the sheer vertical side of a gorge near a waterfall-fed pool located in the hills of the Sahyadri mountains. Like all the locations of Buddhist caves, this one sits near main trade routes and spans six centuries beginning in the 2nd or 1st century B.C.E.[7] A period of intense building activity at that site took place under the Vakataka king Harisena, between 460 and 478 C.E. A profuse variety of decorative sculpture, intricately carved columns and carved reliefs, including exquisitely carved cornices and pilaster, grace the structures. Skilled artisans crafted rock to imitate timbered wood (such as lintels) in construction and grain and intricate decorative carving.[6]

The Badami Cave Temples at Badami, the early Chalukya capital, carved out in the 6th century, provide another example of cave temple architecture. Four cave temples, hewn from the sides of cliffs, include three Hindu and one Jain that contain carved architectural elements such as decorative pillars and brackets as well as finely carved sculpture and richly etched ceiling panels. Many small Buddhist cave shrines appear nearby.[8]

Monolithic rock-cut temples

The Pallava architects started the carving of rock for the creation of a monolithic copies of structural temples. A feature of the rock-cut cave temple distribution until the time of the early Pallavas is that they did not move further south than Aragandanallur, with the solitary exception of Tiruchitrapalli on the south bank of the Kaveri River, the traditional southern boundary between north and south. Also, good granite exposures for rock-cut structures were generally not available south of the river.[9]

Artisans and craftsmen carve a rock cut temple from a large rock, excavating and cutting it to imitate a wooden or masonry temple with wall decorations and works of art. Pancha Rathas provides an example of monolith Indian rock cut architecture dating from the late seventh century located at Mamallapuram, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Ellora cave temple 16, the Kailash Temple, provides a singular example, excavated from the top down rather than by the usual practice of carving into the scarp of a hillside. Artisans crafted the Kailash Temple through a single, huge top-down excavation 100 feet deep down into the volcanic basaltic cliff rock. King Krishna I commissioned the temple in eighth century, requiring more than 100 years to complete.[10] The Kailash Temple, known as cave 16 at Ellora Caves located at Maharastra on the Deccan Plateau, constitutes a huge monolithic temple dedicated to Lord Shiva. Thirty four caves have been built at the site, but the other thirty three caves, Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain, had been carved into the side of the plateau rock. The Kailash Temple gives the effect of a free-standing temple surrounded by smaller cave shrines carved out of the same black rock. The Kailash Temple, carved with figures of gods and goddesses from the Hindu Puranas, along with mystical beings like the heavenly nymphs and musicians and figures of good fortune and fertility.[11] Ellora Caves is also a World Heritage Site.[12]

Free-standing temples

Rock-cut temples and free-standing temples built with cut stone had been developed at the same time. The building of free-standing structures began in fifth century, while rock cut temples continued under excavation until the twelfth century. The Shore Temple serves as an example of a free-standing structural temple, with its slender tower, built on the shore of the Bay of Bengal. Its finely carved granite rocks cut like bricks, dating from the 8th century, belongs with the Group of Monuments at the Mahabalipuram UNESCO World Heritage Site

Cave and temples examples

- Aihole has one Jaina and one Brahmanical temple.

- Badami Cave Temples

- Ellora Caves has twelve Buddhist, 17 Hindu and five Jain temples.[13]

- Kanheri Caves

- Mahabalipuram

- Pancha Rathas

- Shore Temple—structural

- Undavalli caves

- Varaha Cave Temple at Mamallapuram

Notes

- ↑ History of Architecture, Early Civilizations. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, Glossary. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ Art and Archaeology, Prehistoric rock art. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ UNESCO, Rock shelters of Bhimbetka. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ UNESCO, Ajanta Caves. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, Classification of Indian Architecture through the Ages. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ University of California Los Angeles, Ajanta. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ Art and Archaeology, Badami (Western Chalukya). Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ K.V. Soundara Rajan, Rock-cut Temple Styles (Mumbai: Somaily Publications, 1998, ISBN 81 7039 218 7).

- ↑ Art and Archaeology, Monuments of India. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ www.lib.lfc.edu, Kailash Rock Cut Temple. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ UNESCO, Ellora. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica, Ellora Caves. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dehejia, Vidya. Early Buddhist Rock Temples: A Chronological Study. London: Thames and Hudson, 1972. ISBN 0500690014.

- Educational Dimensions Group. Indian Architecture—the Cave, Rock-Cut, and Stupa Temples. Stamford, Conn: Educational Dimensions Group, 1976.

- Soundara Rajan, K.V. Rock-Cut Temple Styles: Early Pandyan Art and the Ellora Shrines. Mumbai: Somaiya Publications, 1998. ISBN 8170392187.

External links

All links retrieved March 1, 2018.

- Photos of rock-cut Bhaja cave.

- New York Times article 'Rock-cut temple of the many faced God', August 19, 1984.

- Ellora Caves UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Elephanta Caves UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- UNESCO World Heritage: Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka.

- Indian rock cut temples.

- Kailesh Rock Cut Temple.

- Kerala Temple Architecture.

- Pallava Art and Architecture.

- Cave architecture.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 00:46:34 | 1 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Indian_rock-cut_architecture | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF