Giorgio Vasari

From Nwe

From Nwe

Giorgio Vasari (July 30, 1511 – June 27, 1574) was an Italian painter and architect, known best for his biographies of Italian artists. Vasari had the opportunity to meet Michelangelo and some of the leading humanists of the time. He was consistently employed by patrons in the Medici family in Florence and Rome, and he worked in Naples, Arezzo, and other places. Some of Vasari’s major paintings include the Palazzo Vecchio’s frescoes, The Lord’s Supper, in the cathedral of Arezzo, and historical decorations of the Sala Regia at the Vatican. Partnered with Vignola and Ammanati, Vasari designed the Villa di Papa Giulio in Rome, but Vasari’s only significant independent architectural work is seen in the Uffizi Palace.

As the first Italian art historian, Vasari initiated the genre of an encyclopedia of artistic biographies that continues today. Vite de' più eccellenti Architetti, Pittori, e Scultori Italiani… (or better known as The Vite) was first published in 1550. In 1571, he was knighted by Pope Pius.

Life

Giorgio Vasari was born in Arezzo, Tuscany, in 1511. When he was very young, at the recommendation of his cousin Luca Signorelli, he became a pupil of Guglielmo da Marsiglia, a skillful painter of stained glass. When Vasari was 16, he was introduced to Cardinal Silvio Passerini who was able to place Vasari in Florence to study in the circle of Andrea del Sarto and his pupils, Rosso Fiorentino and Jacopo Pontormo. Vasari came into close contact with some of the leading humanists of the time. Piero Valeriano, a classical scholar and the author of the Hieroglyphica, was one of Vasari’s teachers. In Florence, Vasari had the opportunity to meet Michelangelo and would continue to idolize him throughout his own artistic career. When Vasari’s father died of the plague, Vasari was left to support to his family. He practiced architecture in order to earn enough money to arrange the marriage of one of his sisters and put another in the Murate at Arezzo.

In 1529, he visited Rome and studied the works of Raffaello Santi (Raphael) and others of the Roman High Renaissance. Vasari's own Mannerist paintings were more admired in his lifetime than afterwards. He was consistently employed by patrons in the Medici family in Florence and Rome, and he worked in Naples, Arezzo, and other places. Some of Vasari’s other patrons included the Cardinal Ippolito de Medici, Pope Clement VII, and the Dukes Alessandro and Cosmo. At the assassination of Vasari’s patron Duke Alessandro, Vasari left Florence and moved from town to town. It was around this time that he launched the plans for his book on artists. Possibly around 1546, while spending an evening in Cardinal Farnese’s house, the bishop of Nocera addressed the need for a literary account of famous artists. Paolo Giovio and Vasari decided to embark on this challenge, but early on, Giovio gave up the idea of writing such a book.

Vasari enjoyed a high reputation during his lifetime and amassed a considerable fortune. In 1547, he built himself a fine house in Arezzo (now a museum honoring him), and spent much labor in decorating its walls and vaults with paintings. He was elected one of the municipal council or priori of his native town, and finally rose to the supreme office of gonfaloniere. In 1563, he helped found the Florence Accademia del Disegno (now the Accademia di Belle Arti Firenze), with the Grand Duke and Michelangelo as capi of the institution and 36 artists chosen as members.

In 1571, he was knighted by Pope Pius. Vasari died in Florence on June 27, 1574. Following his death, work at the Uffizi was completed by Bernardo Buontalenti.

Thought and works

Vasari was perhaps more successful as an architect than as a painter. He was more independent, and his temporary decorations for state ceremonies offered him occasions for experimentation. Partnered with Vignola and Ammanati, Vasari designed the Villa di Papa Giulio in Rome. Vasari’s only significant independent architectural work is seen in the Uffizi Palace, which had been started in 1560. The Uffizi was designed to be the government offices of the new Tuscan state. The finest point of the Uffizi is the spacious loggia overlooking the Arno. Vasari’s other pieces include the Palazzo dei Cavalieri at Piza, the tomb of Michelangelo in Santa Croce, and the Loggie in Arezzo.

Some of Vasari’s major works in Florence are the Palazzo Vecchio’s frescoes, although he never completed the decoration of the cupola of the cathedral. In Rome, he contributed to a large part of the historical decorations of the Sala Regia at the Vatican and the so-called 100 days fresco in the Sala della Cancerria, in the Palazzo San Giorgio. In the cathedral of Arezzo he painted The Lord’s Supper.

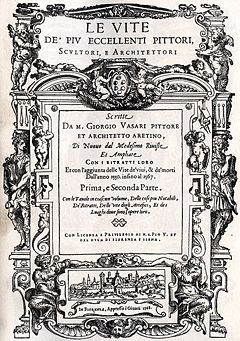

The Vite

Giorgio Vasari’s modern day fame is not due to his architectural or painted creations, but to his book Vite de' più eccellenti Architetti, Pittori, e Scultori Italiani… (better known as simply, The Vite). As the first Italian art historian, he initiated the genre of an encyclopedia of artistic biographies that continues today. Vasari coined the term "Renaissance" (rinascita) in print, though an awareness of the ongoing "rebirth" in the arts had been in the air from the time of Alberti.

Vasari's work was first published in 1550, and dedicated to Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. It included a valuable treatise on the technical methods employed in the arts. It was partly rewritten and enlarged in 1568, and provided with woodcut portraits of artists (some conjectural), entitled Le Vite delle più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori (or, in English, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects). In the first edition, Michelangelo is the climax of Vasari’s story, but the 1568 edition includes a number of other living artists as well as Vasari’s own autobiography.

The work has a consistent and notorious bias in favor of Florentines and tends to attribute to them all the new developments in Renaissance art—for example, the invention of engraving. Venetian art in particular, along with art from other parts of Europe, is systematically ignored. Between his first and second editions, Vasari visited Venice and the second edition gave more attention to Venetian art (finally including Titian) without achieving a neutral point of view.

Vasari’s concept of history, art, and culture pass through three phases. He saw the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, characterized by artists such as Cimabue and Tiotto, as the “infancy” of art. The period of “youthful vigor” came next, seen in the works of Donatello, Brunelleschi, Ghiberti, and Masaccio. The mature period was the last phase, represented by Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo. Vasari’s view of Michelangelo produced a new component in the Renaissance perception of art—the breakthrough of the notion of a "genius."

Vasari's biographies are interspersed with amusing gossip. Many of his anecdotes have the ring of truth, although they are likely inventions. Others are generic fictions, such as the tale of young Giotto painting a fly on the surface of a painting by Cimabue that the older master repeatedly tried to brush away, a genre tale that echoes anecdotes told of the Greek painter Apelles. With a few exceptions, however, Vasari's aesthetic judgment was acute and unbiased. He did not research archives for exact dates, as modern art historians do, and naturally his biographies are most dependable for the painters of his own generation and the immediately preceding one. Modern criticism, with all the new materials opened up by research, has corrected many of his traditional dates and attributions. The work remains a classic even today, though it must be supplemented by modern critical research.

Vasari includes a sketch of his own biography at the end of his Vite, and adds further details about himself and his family in his lives of Lazzaro Vasari and Francesco de' Rossi (Il Salviati). The Lives have been translated into French, German, and English.[1]

The following list respects the order of the book, as divided into its three parts.

Part 1

- Cimabue

- Arnolfo di Cambio|Arnolfo di Lapo

- Nicola Pisano

- Giovanni Pisano

- Andrea Tafi

- Giotto di Bondone (Giotto)

- Pietro Lorenzetti (Pietro Laurati)

- Andrea Pisano

- Buonamico Buffalmacco

- Ambrogio Lorenzetti (Ambruogio Laurati)

- Pietro Cavallini

- Simone Martini

- Taddeo Gaddi

- Andrea Orcagna (Andrea di Cione)

- Agnolo Gaddi

- Duccio

- Gherardo Starnina

- Lorenzo Monaco

- Taddeo Bartoli

Part 2

- Jacopo della Quercia

- Nanni di Banco

- Luca della Robbia

- Paolo Uccello

- Lorenzo Ghiberti

- Masolino da Panicale

- Tommaso Masaccio

- Filippo Brunelleschi

- Donatello

- Giuliano da Maiano

- Piero della Francesca

- Fra Angelico

- Leon Battista Alberti

- Antonello da Messina

- Alessio Baldovinetti

- Fra Filippo Lippi

- Andrea del Castagno

- Domenico Veneziano

- Gentile da Fabriano

- Vittore Pisanello

- Benozzo Gozzoli

- Vecchietta (Francesco di Giorgio e di Lorenzo)

- Antonio Rossellino

- Bernardo Rossellino

- Desiderio da Settignano

- Mino da Fiesole

- Lorenzo Costa

- Ercole Ferrarese

- Jacopo Bellini

- Giovanni Bellini

- Gentile Bellini

- Cosimo Rosselli

- Domenico Ghirlandaio

- Antonio Pollaiuolo

- Piero Pollaiuolo

- Sandro Botticelli

- Andrea del Verrocchio

- Andrea Mantegna

- Filippino Lippi

- Bernardino Pinturicchio

- Francesco Francia

- Pietro Perugino

- Luca Signorelli

Part 3

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Giorgione da Castelfranco

- Antonio da Correggio

- Piero di Cosimo

- Donato Bramante (Bramante da Urbino)

- Fra Bartolomeo Di San Marco

- Mariotto Albertinelli

- Raffaellino del Garbo

- Pietro Torrigiano

- Giuliano da Sangallo

- Antonio da Sangallo

- Raffaello Santi|Raphael

- Guglielmo Da Marcilla

- Simone del Pollaiolo (il Cronaca)

- Davide Ghirlandaio (David and Benedetto Ghirladaio)

- Domenico Puligo

- Andrea da Fiesole (Bregna?)

- Vincenzo Tamagni (Vincenzo da San Gimignano)

- Andrea Sansovino (Andrea dal Monte Sansovino)

- Benedetto Grazzini (Benedetto da Rovezzano)

- Baccio da Montelupo and Raffaello da Montelupo (father and son)

- Lorenzo di Credi

- Boccaccio Boccaccino(Boccaccino Cremonese)

- Lorenzetto

- Baldassare Peruzzi

- Pellegrino da Modena

- Gianfrancesco Penni (Giovan Francesco, also known as il Fattore)

- Andrea del Sarto

- Francesco Granacci

- Baccio D'Agnolo

- Properzia de’ Rossi

- Alfonso Lombardi

- Michele Agnolo

- Girolamo Santacroce

- Dosso Dossi (Dosso and Batista Dossi; the Dosso Brothers)

- Giovanni Antonio Licino (Giovanni Antonio Licino Da Pordenone)

- Rosso Fiorentino

- Giovanni Antonio Sogliani

- Girolamo da Treviso (Girolamo Da Trevigi)

- Polidoro da Caravaggio e Maturino da Firenze (Maturino Fiorentino)

- Bartolommeo Ramenghi (Bartolomeo Da Bagnacavallo)

- Marco Calabrese

- Morto Da Feltro

- Franciabigio

- Francesco Mazzola

- Jacopo Palma (Il Palma)

- Lorenzo Lotto

- Giulio Romano

- Sebastiano del Piombo (Sebastiano Viniziano)

- Perin del Vaga (Perino Del Vaga)

- Domenico Beccafumi

- Baccio Bandinelli

- Jacopo da Pontormo

- Michelangelo Buonarroti

- Titian (Tiziano da Cadore)

- Giulio Clovio

Notes

- ↑ Easyweb, Excerpts from the Vite combined with photos of works mentioned by Vasari. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

Bibliography

- The Lives of the Artists (Oxford World's Classics). Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 019283410X

- Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects, Volumes I and II. Everyman's Library, 1996. ISBN 0679451013

- Vasari on Technique. Dover Publications, 1980. ISBN 048620717X

- Life of Michelangelo. Alba House, 2003. ISBN 0818909358

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boase, T S R . Giorgio Vasari: The Man and the Book. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1979. ISBN 9780691099057

- Cheney, Liana. The Homes of Giorgio Vasari. New York: P. Lang, 2006. ISBN 0820474940

- Cheney, Liana. Giorgio Vasari's Teachers: Sacred & Profane Art. New York: Peter Lang, 2007. ISBN 0820488135

- Rubin, Patricia Lee. Giorgio Vasari: Art and History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780300049091

- Satkowski, Leon George and Ralph Lieberman. Giorgio Vasari: Architect and Courtier. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993. ISBN 0691032866

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved June 22, 2017.

- “Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Artists.” Website created by Adrienne DeAngelis. Currently incomplete, intended to be unabridged, in English.

- “Le Vite." 1550 Unabridged, original Italian.

- “Stories Of The Italian Artists From Vasari.” Translated by E L Seeley, 1908. Abridged, in English.

- Gli artisti principali citati dal Vasari nelle "Vite" (elenco).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Giorgio Vasari history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Giorgio Vasari"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 23:20:22 | 4 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Giorgio_Vasari | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF