History Of India

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia The people of India have had a continuous civilization for 4500 years.

Contents

Ancient History[edit]

The inhabitants of the Indus River valley developed an urban culture based on commerce and sustained by agriculture. Secular chronology, which does not take into account the Great Flood, dates the beginning of this civilization to around 2500 B.C. This civilization declined around 1500 B.C., probably due to environmental changes.

During the second millennium B.C., pastoral, Aryan-speaking tribes migrated from the northwest into the subcontinent, settled in the middle Ganges River valley, and adapted to antecedent cultures.

The political map of ancient and medieval India was made up of myriad kingdoms with fluctuating boundaries. In the 4th and 5th centuries A.D., northern India was unified under the Gupta Dynasty. During this period, known as India's Golden Age, Hindu culture and political administration reached new heights.

Islamic Age[edit]

Islam spread across the subcontinent over a period of 700 years. In the 10th and 11th centuries, Turks and Afghans invaded India and established sultanates in Delhi. In the early 16th century, Babur, a Turkish adventurer and distant relative of Timurlane, established the Mughal Dynasty, which lasted for 200 years. South India followed an independent path, but by the 17th century large areas of South India came under the direct rule or influence of the expanding Mughal Empire. While most of Indian society in its thousands of villages remained untouched by the political struggles going on around them, Indian courtly culture evolved into a unique blend of Hindu and Muslim traditions.

British Period[edit]

see East India Company In 1608, a ship owned by the British East India Company dropped anchor off Surat, marking the start of British colonization. The British presence would remain discreet for 150 years. India offered a sphere of trade activity for merchants and a field for troop maneuvers.

The first British outpost in South Asia was established by the East India Company—informally called the "John Company"—in 1619 at Surat on the northwestern coast. Later in the century, the Company opened permanent trading stations at Madras (now Chennai), Bombay (now Mumbai), and Calcutta (now Kolkata), each under the protection of native rulers.

French failure[edit]

Using the port of Lorient in France, the French East India Company shipped wood, coal, hemp, textiles, foodstuffs, wine, and assorted raw materials and other products to India.

Despite initial commercial successes, the French East India Company lost out to the John Company, its British rival. The French company was too closely tied to the government in Paris and lacked the independence and flexibility of the British counterpart. The French never understood that prosperous trade depended on control of the land. Numerous mistakes and setbacks were suffered because the colonial governor Joseph Dupleix (1697-1763) chose his allies poorly by not daring to abandon the Moguls for the Marathi. Dupleix became governor in 1742 and was recalled by Paris in 1754. French India was reduced to several trading posts, undergoing long death throes. Pondicherry saw new prosperity during the Second Empire, but the Third Republic's policy of assimilation had perverse effects by encouraging a nationalist oligarchy that was hostile to any modernization of the small remaining colony.

Late Mughal era[edit]

Formerly labeled as the dark century of Mughal decadence, the 18th century in India has been an object of rehabilitation by historians in recent decades. Scholars now better appreciate the dynamic economy and the flourishing, brilliant culture. In the political and military spheres, the Indian subcontinent developed into regional states with varying configurations, some constituting original models of a state for the time, like those based on ethnic or religious groupings of Marathas, Jats, and Sikhs. Although Mughal power was on the decline, the new states still sought official investiture, which remained important from a symbolic point of view. Another important feature of the political landscape was the conquering thrust of the Afghans into northern India, which was halted by the Marathas and Sikhs. Starting in the second half of the century developments were played out against the background of the powerful rise of the East India Company which, given the situation during that troubled period, wound up becoming the referee for the entire subcontinent. Literature, music, and the visual arts, however, glittered in princely courts despite military and political difficulties.

Colonial wars[edit]

In 1757, the battle of Plassey confirmed British supremacy, although the British avoided exercising direct political power in India even as senior civil servants began to play an ever-increasing role.

The disastrous defeat of France in the Seven Years' War (1758–63), the decline of French influence in India, and the growing British predominance there led France in 1778 to plan a new war against Britain in coordination with the American Revolution. The strategy included an expedition against British spheres of influence in India, which was intended to draw a large part of the British navy into the Indian Ocean. France found an ally in Hyder Ali, ruler of Mysore and a leader of the princes opposed to the growing domination of the British. France sent a military assistance group to Hyder Ali to reinforce his artillery and his cavalry, but in a series of campaigns he failed to inflict a decisive defeat upon the British. Although the war between Britain and France ended in 1783, the French continued to assist Tipu Sultan, the son and successor of Hyder Ali, until he was defeated by the British and died in 1799.

19th century[edit]

The British expanded their influence from these footholds until, by the 1850s, they controlled most of South Asia, including present-day India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. The Victorian era brought new values and led to greater Westernization.

Missionaries[edit]

The arrival of Christian missionaries in the 16th century and of more militant missions in the 18th century with the British conquest led to defensive reactions by local religions, followed later by imitation. Hindus and Muslims acquired a proselytizing fervor previously unknown as they tried to counter the Christians by imitating their methods. In the 1980s political conflict with Christians and Muslims led the Hindus to aggressive efforts to reconvert formerly Hindu untouchables. This contest for souls contributed to the rise of communal violence in the subcontinent.

The inclusion of a clause within the 1813 charter of the East India Company, obliging the company to assist efforts to introduce Christianity to India was called the "pious clause". Many historians have emphasized it marked the beginnings of an aggressive proselytizing imperialism. However the evangelicals' victory was more rhetorical than real, for the John Company and its officials in India continued to view missionary activity with alarm and even in some cases distaste.

Sepoy Rebellion[edit]

The Sepoy rebellion (1857–58) meant the end of Mughal power and reduced India to a complete British colony - the jewel of the empire. The British Raj reached its apogee between 1885 and 1918.

In 1857, an unsuccessful rebellion in north India led by Indian soldiers seeking the restoration of the Mughal Emperor caused the British Parliament to transfer political power from the East India Company to the Crown. Britain began administering most of India directly, while controlling the rest through treaties with local rulers.

In the late 1800s, the first steps were taken toward self-government in British India with the appointment of Indian councilors to advise the British Viceroy and the establishment of Provincial Councils with Indian members; the British subsequently widened participation in Legislative Councils.

Before 1800, land rights and economic relations between rural Indians had been based on social relations of caste and dependence. By introducing a land tax system founded on modern concepts of property and contract, then by encouraging the development of commercial agriculture, the British unleashed a process of economic and social change in the countryside, consolidating the domination of large landlords and peasant elites. However, the increase in population, the growing rarity of land, and the stagnation of agricultural methods exposed the colony to the risk of catastrophic famines right into the early 20th century, despite favorable agricultural prices.

Railways[edit]

India provides an example of the British Empire pouring its money and expertise into a very well built system designed for military reasons (after the Mutiny of 1857), and with the hope that it would stimulate industry. The system was overbuilt and much too elaborate and expensive for the small amount of freight traffic it carried. However, it did capture the imagination of the Indians, who saw their railways as the symbol of an industrial modernity—but one that was not realized until a century or so later.

The British built a superb system in India. However, Christensen (1996) looks at of colonial purpose, local needs, capital, service, and private-versus-public interests. He concludes that making the railways a creature of the state hindered success because railway expenses had to go through the same time-consuming and political budgeting process as did all other state expenses. Railway costs could therefore not be tailored to the timely needs of the railways or their passengers.[1]

By the 1940s, India had the fourth longest railway network in the world. Yet the country's industrialization was delayed until after independence in 1947 by British colonial policy. Until the 1930s, both the Indian government and the private railway companies hired only European supervisors, civil engineers, and even operating personnel, such as locomotive drivers (engineers). The government's "Stores Policy" required that bids on railway matériel be presented to the India Office in London, making it almost impossible for enterprises based in India to compete for orders. Likewise, the railway companies purchased most of their matériel in Britain, rather than in India. Although the railway maintenance workshops in India could have manufactured and repaired locomotives, the railways imported a majority of them from Britain, and the others from Germany, Belgium, and the United States. The Tata company built a steel mill in India before World War I but could not obtain orders for rails until the 1920s and 1930s.

Expelling the British[edit]

The roots of the Indian nationalist movement date back to the 1870s, leading to the founding of the Indian National Congress in 1885. The decolonization movement began in 1919. The year 1919 was one of serious incidents, notably the Amritsar massacre, which marked a point of no return in the history of British India. From that moment onward, the colonial government had to face a nationalist opposition capable of coordinating mass agitation. The noncooperation movement of 1920-22 and the civil disobedience of 1930-34 demonstrated the growing scope of anti-British mobilization in India. In an attempt to stabilize the situation, London granted a more liberal constitution in 1935, which notably reinforced provincial autonomy. But the Congress Party took advantage of this move to form governments in eight provinces, thereby consolidating its political foothold.

The Amritsar massacre of 1919 sounded the death knell of the British colonial adventure. Agrarian resistance and revolt were chronic during the colonial period, and began taking a modern turn in the 1920s when peasants, led by Mohandas K. Gandhi, began manifesting their discontent in the context of political demands made by the nationalist intelligentsia, progressively transforming the emancipation movement into an unstoppable mass movement. At the same time the British lost interest in India, seeing it more as a burden than a glory.[2]

Beginning in 1920, Gandhi transformed the Indian National Congress political party into a mass movement to campaign against British colonial rule. The party used both parliamentary and nonviolent resistance and non-cooperation to agitate for independence.

By the mid-1930s, India was still the cornerstone of the world's largest colonial empire, but the Empire had been badly shaken by World War I, the Great Depression, and the effective independence of the dominions such as Canada. The empire was costing Britain heavily. To facilitate the inevitable trnasition, London organized the first true elections, sparking the confrontation of two great leaders - Mohammed Ali Jinnah (who founded Pakistan) and Jawaharlal Nehru (who led independent India).

Social history[edit]

The Family[edit]

The history of the Hindu family in India was shaped by Hindu. The reference model is the "Hindu joint family," which primarily represents a ritual and patrimonial unit centered on the values of sacrifice and debt. In practice this domestic organization is found most often among wealthier farming castes and within merchant communities, whereas the lower classes tend to live in conjugal-type families of husband-wife-and-children. Since the 19th century, the family has been the object of numerous legal reforms. Since the 1990s rapid economic growth and the attention focused on the rising status of women, together with high demographic growth rates, placed the institution of the family at the center of tensions, straining India's social fabric.

Environmentalism[edit]

Dietrich Brandis was the first Inspector General of Forests (IGF) of British India (1862-1881) and founder of the Indian Forest Department. He tried to set the policy regarding forest management and the regulation of forest use. His view was that state control over the forests should be limited to forest areas of high commercial value, the management of the rest being left to village communities in the form of village forests. Howeverr he was overruled and the prevailing view favored an extensive state monopoly of forest control combined with a strict regulation of forest use by the local people. It is this view that was embodied in the Indian Forest Act of 1878, which is still in force today. The hardships local populations have to face on this account have, however, stimulated local initiatives in a great many places in recent times, and through these efforts the century-old views of Brandis are now regaining ground in India.

Deforestation has developed in the central Western Ghats of India over the last two hundred years. A consciousness of the ecological dangers of uncontrolled deforestation existed in official circles during the first half of the 19th century. In order to meet the requirements of the colonial state a centralized system of forest management was instituted in the 1860s. Forest regulations drastically curtailed the rights of access of the local populations to the forests for collection of forest produce and grazing. The Forest Department, being considered as a source of surplus revenue for the Imperial government, had to give priority to commercial exploitation and the cultivation of valuable species of trees over the interests of the local peasants. The Forest Department pursued a policy of gradual eradication of shifting cultivation. The traditional equilibrium between agriculture and forest was jeopardized, as the area of forest that was conceded to the village communities proved too small for a growing population. Periodic outbursts of mass resistance to forest regulations occurred, especially from the 1920s when popular discontent tended to merge with nationalist agitation.

War and Independence[edit]

During the First World War (1914–18) millions of Indians had served with honor and distinction in the British armed forces. During the Second World War (1939–45) there was far less volunteering. Although Britain used India as a base for its war in Burma, it was a minor front. Gandhi and Nehru led a programme of passive resistance, meaning refusal to help the British war effort. In response the British withdrew commercial shipping, diverting it to the war effort. Major famines swept India during the war, killing millions. Neither the British government nor the Congress shadow government moved to alleviate the famine.

With Indians increasingly united in their quest for independence, a war-weary Britain led by Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee began in earnest to plan for the end of its suzerainty in India. Nehru's believed India's communal problems were the artificial result result of the British policy of divide and rule. Nehru's condescension toward Mohammed Ali Jinnah and the Muslim League, and belief that the Congress Party represented Muslim as well as Hindu nationalist interests in India resulted in his doing everything possible to avoid partition.

Strategic colonial considerations, as well as political tensions between Hindus and Muslims, led the British to partition British India into two separate states: India, with a Hindu majority; and Pakistan, which consisted of two "wings," East and West Pakistan—currently Bangladesh and Pakistan—with Muslim majorities.

On August 15, 1947, India became independnet, with Jawaharlal Nehru as Prime Minister. Even before the British army left, there were major violent confrontations between Moslems and Hindus; in 1946-47 massive communal violence erupted that killed millions of people, created tens of millions of refugees and left permanent hatreds and fears.

Congress rules[edit]

After independence, the Indian National Congress, the party of Mohandas K. Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, ruled India under the leadership first of Nehru and then his daughter (Indira Gandhi) and grandson (Rajiv Gandhi), with the exception of brief periods in the 1970s and 1980s, during a short period in 1996, and the period from 1998–2004, when a coalition led by the Bharatiya Janata Party governed.

Indira Gandhi[edit]

Prime Minister Nehru governed the nation until his death in 1964. Nehru was succeeded by Lal Bahadur Shastri, who also died in office. In 1966, power passed to Nehru's daughter, Indira Gandhi (1917–84), Prime Minister from 1966 to 1977, and again 1980–84.[3]

Intense political factionalism prevailed her first term as prime minister, 1966–71. Conservative elements who had supported her election - thinking she could be "molded" to their will - fought back bitterly (but unsuccessfully) when she proved to be an ardent defender of Nehru's liberal political philosophy. In 1969 the Indian National Congress split into two factions. The majority, led by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, promoted socialist economic and social reforms. The conservative minority, called the Syndicate, advocated more capitalism as the solution to the nation's massive poverty. Cooperating with other conservative parties, the Syndicate weakened Gandhi's popular programs by threatening the parliamentary majority of the Congress party. Mrs Gandhi responded by closer links with leftist parties.

Considerable real economic growth took place, often in spite of or contrary to her proposals. Prosperity enabled Mrs. Gandhi to win a landslide reelection victory in 1971. It partly resulted from her reputation for strong leadership, and also resulted from the effects of the New Economic Policy, implemented in 1966. After hesitant beginnings in the early 1960s the Green Revolution rapidly improved food production and spurred the entire economy after 1967. She nationalized India's banks in 1967 to allow for easy credit. Social discontent resulting from the Green Revolution was still limited.

In foreign policy she led the nation to a triumphant victory in a major war with Pakistan in 1972. It resulted in the independence of Bangladesh, which had revolted over the widespread mistreatment by Pakistan. Mrs. Gandhi's pragmatic, coldly calculated friendly relationships with the Soviet Union and her hostile attitude toward the United States left India a more important and independent regional power than it had been under her father. Her nuclear policy was characterized by the refusal to sign the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty, insistence on the further development of peaceful uses of atomic energy, and maintenance of a nuclear technological capability in response to developments in Pakistan and China.[4]

State of Emergency[edit]

In 1975, beset with deepening political and economic problems, Mrs. Gandhi declared a state of emergency and suspended many civil liberties. Although India had a strong tradition of democracy, that tradition was challenged when Mrs. Gandhi moved toward a personal dictatorship. In the summer of 1975, following a long siege of political invective and legal reverses, she arrested her chief critic Jayaprakash Narayan and thousands of his political supporters and suspended the constitution under the Defence of India Rules. She said the drastic action was necessary to preserve national unity. Mrs. Gandhi then issued edicts to curtail rising prices, improve the efficiency of government, and control crime and violence. The opposition, however, maintains that these things were accomplished only at the price of higher unemployment, increased government bureaucracy, and growth of hoarding, smuggling, and black marketeering. The newspapers of India were suppressed by heavy censorship rulings and the laws regarding the office of prime minister were altered to virtually ignore the role of the Indian Parliament.

Mrs Gandhi defeated by Janata[edit]

Seeking a mandate at the polls for her policies, she called for elections in 1977, only to be defeated by Morarji Desai, who headed the Janata Party, an amalgam of five opposition parties.

In 1979, Desai's Government crumbled. Charan Singh formed an interim government, which was followed by Mrs. Gandhi's return to power in January 1980.

Assassinations and instability[edit]

On October 31, 1984, Mrs. Gandhi was assassinated by Sikh bodyguards, followed by a nationwide outburst of violent attacks on Sihks. Her son Rajiv Gandhi, was chosen by the Congress (I)--for "Indira"—Party to take her place. His Congress government was plagued with allegations of corruption resulting in an early call for national elections in 1989.

Although Rajiv Gandhi's Congress Party won more seats than any other single party in the 1989 elections, he was unable to form a government with a clear majority. The Janata Dal, a union of opposition parties, then joined with the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) on the right and the Communists on the left to form the government. This loose coalition collapsed in November 1990, and the Janata Dal, supported by the Congress (I), came to power for a short period, with Chandra Shekhar as Prime Minister. That alliance also collapsed, resulting in national elections in June 1991.

While campaigning in Tamil Nadu on behalf of Congress (I), Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated on May 27, 1991, apparently by Tamil extremists from Sri Lanka, unhappy with India's armed intervention to try to stop the civil war there.

Congress returns[edit]

In the 1991 elections, Congress (I) won 213 parliamentary seats and returned to power at the head of a coalition, under the leadership of P.V. Narasimha Rao. This Congress-led government, which served a full 5-year term, dropped much of the socialism associated with Nehru. Instead it initiated a gradual process of economic liberalization and reform, which opened the Indian economy to global trade and investment. India's domestic politics also took new shape, as the nationalist appeal of the Congress Party gave way to traditional caste, creed, regional, and ethnic alignments, leading to the founding of a plethora of small, regionally based political parties.

Political instability again[edit]

The final months of the Rao-led government in the spring of 1996 were marred by several major corruption scandals, which contributed to the worst electoral performance by the Congress Party in its history. The Hindu-nationalist BJP emerged from the May 1996 national elections as the single-largest party in the Lok Sabha but without a parliamentary majority. Under Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the subsequent BJP coalition lasted only 13 days. With all political parties wishing to avoid another round of elections, a 14-party coalition led by the Janata Dal formed a government known as the United Front, under the former Chief Minister of Karnataka, H.D. Deve Gowda. His government collapsed after less than a year, when the Congress Party withdrew its support in March 1997. Inder Kumar Gujral replaced Deve Gowda as the consensus choice for Prime Minister at the head of a 16-party United Front coalition.

In November 1997, the Congress Party again withdrew support from the United Front. In new elections in February 1998, the BJP won the largest number of seats in Parliament—182—but fell far short of a majority. On March 20, 1998, the President approved a BJP-led coalition government with Vajpayee again serving as Prime Minister. On May 11 and 13, 1998, this government conducted a series of underground nuclear tests, spurring U.S. President Bill Clinton to impose economic sanctions on India pursuant to the 1994 Nuclear Proliferation Prevention Act.

In April 1999, the BJP-led coalition government fell apart, leading to fresh elections in September. The National Democratic Alliance—a new coalition led by the BJP—won a majority to form the government with Vajpayee as Prime Minister in October 1999. The NDA government was the first in many years to serve a full five-year term, providing much-needed political stability.

The Kargil conflict in 1999 and an attack by terrorists on the Indian Parliament in December 2001 led to increased tensions with Pakistan.

Hindu-Muslim violence[edit]

Hindu nationalists supportive of the BJP agitated to build a temple on a disputed site in Ayodhya, destroying a 17th-century mosque there in December 1992, and sparking widespread religious riots in which thousands, mostly Muslims, were killed. In February 2002, 57 Hindu volunteers returning from Ayodhya were burnt alive when their train caught fire. Alleging that the fire was caused by Muslim attackers, anti-Muslim rioters throughout the state of Gujarat killed over 900 people and left 100,000 homeless. This led to accusations that the BJP-led Gujarat state government had not done enough to contain the riots, or arrest and prosecute the rioters.

The ruling BJP-led coalition was defeated in a five-stage election held in April and May 2004, and a Congress-led coalition, known as the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), took power on May 22 with Manmohan Singh as Prime Minister. The UPA's victory was attributed to dissatisfaction among poorer rural voters that the prosperity of the cities had not filtered down to them, and rejection of the BJP's Hindu nationalist agenda.

Friendly relations with U.S.[edit]

The Congress-led UPA government has continued many of the BJP's foreign policies, particularly improving relations with the U.S. Prime Minister Singh and President George W. Bush concluded a landmark U.S.-India strategic partnership framework agreement on July 18, 2005. In March 2006, President Bush visited India to further the many initiatives that underlie the new agreement. The strategic partnership is anchored by a historic civil nuclear cooperation initiative and includes cooperation in the fields of space, high-technology commerce, health issues, democracy promotion, agriculture, and trade and investment.

for recent history see India

Historiography[edit]

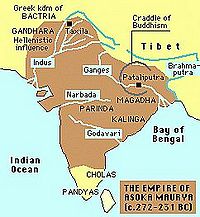

The discovery and elucidation of India's past owes much to European scholars. William Jones's (1746–94) identification of "Sandrocottus" of Greek history with Chandragupta Mauriya (ruled 321-297 B.C.) established a fixed point in ancient Indian chronology. James Prinsep's (1793-1878) deciphering of the inscriptions of Asoka (ruled 268-231 B.C.) and identification of the "Piyyadasi" mentioned in Asoka's edicts as Asoka himself was another major contribution.

Judgment on colonial rule[edit]

A raging debate among scholars continues regarding the good-or-bad economic impact of British imperialism on India. The issue was raised by conservative British conservative politician Edmund Burke who in the 1780s vehemently attacked the East India Company, claiming that Warren Hastings and other top officials had ruined the Indian economy and society. Indian historian Rajat Kanta Ray (1998) continues this line of attack, saying the new economy brought by the British in the 18th century was a form of "plunder" and a catastrophe for the traditional economy of Mughal India. Ray accuses the British of depleting the food and money stocks and imposing high taxes that helped cause the terrible famine of 1770, which killed a third of the people of Bengal.[5]

On the other hand, P. J. Marshall shows that recent scholarship has reinterpreted the received view that the prosperity of the formerly benign Mughal rule gave way to poverty, and anarchy. Marshall argues the British takeover did not make any sharp break with the past. British control was delegated largely through regional Mughal rulers and was sustained by a generally prosperous economy for the rest of the 18th century. Marshall notes the British went into partnership with Indian bankers and raised revenue through local tax administrators, and kept the old Mughal rates of taxation.[6] Instead of the Indian nationalist account of the British as alien aggressors, seizing power by brute force and impoverishing all of India, Marshall presents the interpretation, supported by many scholars in both India and the West, in which the British were not in full control but instead were players in what was primarily an Indian play and in which their rise to power depended upon excellent cooperation with Indian elites. Marshall admits that much of his interpretation is still rejected by many historians working in India today, who prefer to bash the British.[7]

See also[edit]

- Indian Painting

- Adiabene sending station to the Far East

- Opposition to the partition of India

Bibliography[edit]

Surveys[edit]

- Allan, J. T. Wolseley Haig, and H. H. Dodwell, The Cambridge Shorter History of India (1934) online edition

- Brown, Judith M. Modern India: The Origins of an Asian Democracy (2nd ed. 1994) 464 pgs online edition

- Daniélou, Alain. A Brief History of India (2003)

- Guha, Ramachandra. India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy (2008) excerpt and text search

- Habib, Irfan. Atlas of the Mughal Empire: Political and Economic Maps (1982).

- James, Lawrence. Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (1997) ISBN 0-316-64072-7 excerpt and online search from Amazon.com

- Keay, John. India: A History (2001) excerpts and online search from Amazon.com

- Kishore, Prem and Anuradha Kishore Ganpati. India: An Illustrated History (2003)

- Kulke, Hermann and Dietmar Rothermund. A History of India. 4th ed. (2004) online edition from Questia; excerpts and online search from Amazon.com

- Lal, Deepak. The Hindu Equilibrium: India C.1500 B.C.-2000 A.D. (2nd ed. 2005).

- Majumdar, R. C. et al. An Advanced History of India London: Macmillan. 1960. ISBN 0-333-90298-X

- Mcleod, John. The History of India (2002) 225pp online edition

- Rawlinson, H. G. India: A Short Cultural History (1952) 454 pgs. online edition

- Richards, John F. The Mughal Empire (The New Cambridge History of India) (1996) excerpt and online search from Amazon.com

- Sardesai, D. R. India: The Definitive History (2007), 486pp excerpts and online search from Amazon.com

- Smith, Vincent. The Oxford History of India (1981), original edition 1915

- Smith, Vincent. The Oxford student's history of India (1915) online edition

- Spear, Percival. The History of India Vol. 2 (1990)

- Thapar, Romila. Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 (2004) excerpts and online search from Amazon.com

- Wolpert, Stanley. A New History of India (7th ed. 2003) 544pp excerpt and online search from Amazon.com

- Jackson, A.V. et al., eds. History of India (1906-1907)

- v.l. From the earliest times to the sixth century B.C., by R.C. Dutt. online edition

- v.2. From the sixth century B.C. to the Mohammedan conquest, by V.A. Smith. online edition

- v.3. Mediaeval India from the Mohammedan conquest to the reign of Akbar the Great, by S. Lane-Poole. online edition

- v.4. From the reign of Akbar the Great to the fall of the Moghul empire, by S. Lane-Poole. online edition

- v.5. The Mohammedan period as described by its own historians, by Sir H.M. Elliot online edition

- v.6. From the first European settlements to the founding of the English East India Company, by Sir W.W. Hunter. online edition

- v.7. The European struggle for Indian supremacy in the seventeenth century, by Sir W.W. Hunter. online edition

- v.8. From the close of the seventeenth century to the present time, by Sir. A.C. Lyall. online edition

- v.9. Historic accounts of India by foreign travellers, classic, oriental, and occidental, by A.V.W. Jackson online edition

Economic history[edit]

- Balachandran, G. ed. India and the World Economy, 1850-1950 Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-567234-8.

- Chaudhuri, K. N.Trade and Civilisation in the Indian Ocean: An Economic History from the Rise of Islam to 1750 (1985)

- Das, Gurcharan. India Unbound: The Social and Economic Revolution from Independence to the Global Information Age (2002). excerpt and online search from Amazon.com

- Dutt, Romesh. The Economic History of India in the Victorian Age (1908) online edition

- Ludden, David, ed. New Cambridge History of India: An Agrarian History of South Asia (1999). excerpt and online search from Amazon.com

- Habib, Irfan. Agrarian System of Mughal India (1963, revised edition 1999).

- Habib, Irfan. Atlas of the Mughal Empire: Political and Economic Maps (1982).

- Habib, Irfan. Indian Economy, 1858-1914 (2006).

- Raychaudhuri, Tapan and Irfan Habib, eds. The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 1, c. 1200-c. 1750 (1982).

- Kumar, Dharma and Meghnad Desai, eds. The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 2, c.1751-c.1970 (1983).

- Tomlinson, B. R. et al.The Economy of Modern India, 1860-1970 (1996) (The New Cambridge History of India)

- Larue, C. Steven. The India Handbook (1997) (Regional Handbooks of Economic Development).

- Panagariya, Arvind. India: The Emerging Giant (2008) 544 pp., ISBN 978-0-19-531503-5 The major recent history; for advanced readers. excerpt and text search

- Rothermund, Dietmar. An Economic History of India: From Pre-Colonial Times to 1991 (1993)

- Rudolph, Lloyd I. In Pursuit of Lakshmi: The Political Economy of the Indian State (1987).

- Roy, Tirthankar. The Economic History of India 1857-1947 (2006). excerpt and online search from Amazon.com

India in the British Empire[edit]

- Cain, P. J. and A.G. Hopkins. British Imperialism, 1688-2000 (2nd ed. 2001), 739pp, detailed economic history that presents the new "gentlemanly capitalists" thesis excerpt and text search

- Louis, William. Roger (general editor), The Oxford History of the British Empire, 5 vols. (1998–99).

- vol 1 "The Origins of Empire" ed. by Nicholas Canny

- vol 2 "The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall excerpt and text search

- vol 3 The Nineteenth Century edited by William Roger Louis, Alaine M. Low, Andrew Porter; (1998). 780 pp.. online edition, also excerpt and text search

- vol 5 "Historiography" ed, by Robin W. Winks (1999) excerpt and text search

- Marshall, P. J. (ed.), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire (1996). excerpt and text search

Primary sources[edit]

- Jackson, A.V. et al., eds. History of India (1907) v.9. Historic accounts of India by foreign travellers, classic, oriental, and occidental, by A.V.W. Jackson online edition

References[edit]

- ↑ * R. O. Christensen, "The State and Indian Railway Performance, 1870-1920" in Terri Gourvish, ed. Railways vol 1 (1996); George ston, History of the East Indian Railway (1906) 281 pages; online at Google

- ↑ Winston Churchill in the 1930s argued that the Empire should tighten its hold on India, but found little support..

- ↑ see Pranay Gupte, Mother India: A Political Biography of Indira Gandhi (1992). 320 pp.; Pupul Jayakar, Indira Gandhi: An Intimate Biography (1993). 448 pp.; Inder Malhotra, Indira Gandhi: A Personal and Political Biography. (1991). 363 pp.

- ↑ Surjit Mansingh, India's Search for Power: Indira Gandhi's Foreign Policy. (1984). 405 pp.

- ↑ Rajat Kanta Ray, "Indian Society and the Establishment of British Supremacy, 1765-1818," in The Oxford History of the British Empire: vol. 2, The Eighteenth Century ed. by P. J. Marshall, (1998), pp 508-29

- ↑ Professor Ray agrees that the East India Company inherited an onerous taxation system that took one-third of the produce of Indian cultivators.

- ↑ P.J. Marshall, "The British in Asia: Trade to Dominion, 1700-1765," in The Oxford History of the British Empire: vol. 2, The Eighteenth Century ed. by P. J. Marshall, (1998), pp 487-507

Categories: [Indian History] [India] [British Empire] [Featured articles]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/28/2023 10:18:52 | 63 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/History_of_India | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF