Karakoa

From Handwiki

From Handwiki

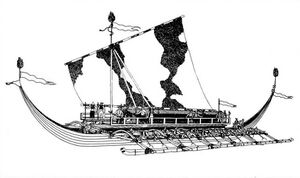

Karakoa were large outrigger warships from the Philippines . They were used by native Filipinos, notably the Kapampangans and the Visayans, during seasonal sea raids. Karakoa were distinct from other traditional Philippine sailing vessels in that they were equipped with platforms for transporting warriors and for fighting at sea. During peacetime, they were also used as trading ships. Large karakoa, which could carry hundreds of rowers and warriors, were known as joangas (also spelled juangas) by the Spanish.

Panday Piray of Pampanga, Philippines, was also known for forging heavy bronze lantaka to be mounted on Lakan's (Naval Chief/Commander) ships called 'caracoas' doing battle against the Spanish invaders and cannons were also commissioned by Rajah Sulayman for the fortification of Maynila.

By the end of the 16th century, the Spanish denounced karakoa ship-building and its usage. It later led to a total ban of the ship and the traditions assigned to it. In recent years, the revitalization of karakoa ship-building and its usage are being pushed by some scholars from Pampanga.[citation needed]

Etymology

Karakoa was usually spelled as "caracoa" during the Spanish period. The name and variants thereof (including caracora, caracore, caracole, corcoa, cora-cora, and caracolle) were used interchangeably with various other similar warships from maritime Southeast Asia, like the kora kora of the Maluku Islands.[1][2]

The origin of the names are unknown. Some authors propose that it may have been derived from Arabic Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (pl. Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.) meaning "large merchant ship" via Portuguese caracca (carrack). However, this is unlikely as the oldest Portuguese and Spanish sources never refer to it as "caracca", but rather "coracora", "caracora" or "carcoa". The Spanish historian Antonio de Morga explicitly says that the name karakoa is ancient and indigenous to the Tagalog people in Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas (1609). There are also multiple cognates in the names of other vessels of Austronesian vessels (some with no contact with Arab traders) like the Ivatan karakuhan, Malay kolek, Acehnese kolay, Maluku kora kora, Banda kolekole, Motu kora, and the Marshallese korkor. Thus it is more likely that it is a true Malayo-Polynesian word and not a loanword.[3]

Description

Karakoa is a type of balangay (Philippine lashed-lug plank boats).[3] It can be differentiated from other balangay in that they possessed raised decks (burulan) amidships and on the outriggers, as well as S-shaped outrigger spars. They also had sharply curved prows and sterns, giving the ships a characteristic crescent shape. Their design was also sleeker and faster than other balangay, even though karakoa were usually much larger. Like balangay, they can be used for both trade and war. Their main use, however, were as warships and troop transports during the traditional seasonal sea raids (mangayaw) or piracy (especially against European trade ships). They were estimated to have speeds of up to 12 to 15 knots.[4][5][6][7][8]

.jpg)

The Spanish priest Francisco Combés described karakoa in great detail in 1667. He was also impressed by the speed and craftsmanship of the vessels, remarking:[10]

"That care and attention, which govern their boat-building, cause their ships to sail like birds, while ours are like lead in this regard."

Like other outrigger vessels, karakoa had very shallow drafts, allowing them to navigate right up to the shoreline. The hull was long and narrow and was made from lightweight materials. The entire vessel can be dragged ashore when not in use or to protect it from storms.[5][7][8]

.jpg)

The keel was essentially a dugout made from the single trunk of hardwoods like tugas (Vitex parviflora) or tindalo (Afzelia rhomboidea). Strakes were built up along the sides of the keel, forming the hull. They were usually made from lawaan wood (Shorea spp.) and were tightly fitted to the keel and with each other by dowels reinforced further with fiber lashings (usually from sugar palm) on carved lugs. Ribs for support and seating connected the strakes across, which were also lashed together with fiber. The use of dowels and lashings instead of nails made the hull flexible, able to absorb collisions with underwater objects that would have shattered more rigid hulls. Strongly curved planks were fitted at both ends of the keel, giving the ship a crescent-shaped profile. These were usually elaborately carved into serpent or dragon (bakunawa) designs. Tall poles festooned with colorful feathers or banners were also affixed here, called the sombol (prow) and the tongol (stern).[note 1] The anterioposterior symmetry allowed the boat to reverse direction quickly by simply having the rowers turn around in their seats.[5][7][8]

Karakoa had tripod bamboo masts (two or three in larger vessels), rigged with either crab-claw sails or rectangular tanja sails (lutaw). The sails were traditionally made from woven plant fibers (like nipa), but were later replaced with materials like linen. In addition to the sails, karakoa had a crew of rowers (usually horohan warriors from the alipin caste) with paddles (bugsay),[note 2] or oars (gaod or gaor)[note 3] on either side of the hull. In between the rowers was an open space used as a passage for moving fore and aft of the ship. Various chants and songs kept the pace and rhythm of the rowers. Above the rowers was a distinctive raised platform (burulan) made of bamboo where warriors (timawa) and other passengers stood, so as to avoid interfering with the rowers. This platform can be covered by an awning of woven palm leaves (kayang, Spanish: cayanes) during hot days or when it rains, protecting the crew and cargo. Karakoa lacked a central rudder and was instead steered by large oars controlled by the nakhoda (helmsman) seated in a covered structure near the back of the ship. These oars could be raised at a moment's notice to avoid obstructions like shallow reefs.[7][8]

The hull was connected to the outrigger structure, which was composed of the S-shaped crosswise outrigger spars (tadik) attached to the outrigger floats (katig or kate) at water level. The katig provided stability and additional buoyancy, preventing the boat from capsizing even when the hull is entirely flooded with water. The katig, like the hull itself, curve upwards at both ends, minimizing drag and preventing rolling. Katig were usually made with large bamboo poles traditionally fire hardened and bent with heat. In between the katig and the hull was another lengthwise beam called the batangan. This served as the support structure for two additional burulan on either side of the boat called the pagguray, as well as additional seating for rowers called daramba.[7][8]

Karakoa can reach up to 25 metres (82 ft) in length. Very large karakoa can seat up to a hundred rowers on each side and dozens warriors on the burulan.[5][7][8] Vessels of this size were usually royal flagships and were (inaccurately) referred to by the Spanish as joangas or juangas (sing. joanga, Spanish for "junk", native dyong or adyong).[8][11]

Sea raiding

Karakoa were an integral part of the traditional sea raiding (mangayaw) of Filipino thalassocracies. They were maritime expeditions (usually seasonal) against enemy villages for the purposes of gaining prestige through combat, taking plunder, and capturing slaves or hostages (sometimes brides).[5]

Before a raid, Visayans performed a ceremony called the pagdaga, where the prow and the keel of the karakoa warships were smeared with blood drawn from a captured member of the target enemy settlement. Karakoa and attending smaller ships usually raid in fleets called an abay. A fast scout ship, called a dulawan (lit. "visitor") or lampitaw, is usually sent in advance of the abay. If intercepted by defending enemy ships, karakoa can engage in ship-to-ship battles called bangga. The pursuit of enemy ships is called banggal.[5]

Warriors aboard karakoas were shielded from projectiles by removable panels of bamboo or woven nipa, in addition to kalasag personal shields. They were commonly armed with various swords like the kalis and metal-tipped spears called bangkaw. In addition, karakoa also had throwing javelins called sugob, which were thrown in large numbers at enemy ships. Unlike the bangkaw, they didn't have metal tips and were meant to be disposable. They were made from sharpened bagakay (Schizostachyum lumampao) bamboo whose compartments were filled with sand to add weight for throwing. They sometimes had wooden tips laced with snake venom. Short-ranged bows (pana or busog) were also sometimes used in close-quarter volleys at enemy ships.[5]

Like other ships for trade and war in maritime Southeast Asia, karakoa were also usually armed with one or more bronze or brass swivel guns called lantaka,[5] and sometimes also larger guns.[12]

There was a great deal of honor involved in participating in a raid. Exploits during raids were recorded permanently in the tattoos of Visayan warriors and nobility (timawa and tumao), earning them the name of pintados ("the painted ones") from the Spanish.[5]

See also

- Balangay

- Lashed-lug boat

- Lanong

- Garay

- Kora kora, similar warships from the Maluku Islands

- Outrigger boat

- Paraw

- Borobudur ship

- Jong, large cargo and passenger ship from Java

Notes

- ↑ Tongol means "to behead" or "severed head" in Visayan, which may have been the original item placed on the stern pole

- ↑ Bugsay were carved from a single piece of wood, around 1 m (3.3 ft) in length, with leaf-shaped blades

- ↑ Gaod had disc-shaped blades

References

- ↑ Charles P.G. Scott (1896). "The Malayan Words in English (First Part)". Journal of the American Oriental Society 17: 93–144. https://books.google.com/books?id=9MJBAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ Raymond Arveiller (1999). Max Pfister. ed. Addenda au FEW XIX (Orientalia). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie. 298. Max Niemeyer. p. 174. ISBN 9783110927719. https://books.google.com/books?id=8p7yCQAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Haddon, A. C. (January 1920). "The Outriggers of Indonesian Canoes.". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 50: 69–134. doi:10.2307/2843375. http://www.survivorlibrary.com/library/the_outriggers_of_indonesian_canoes_1920.pdf.

- ↑ Scott, William Henry (1982). "Boat-Building and Seamanship in Classic Philippine Society". Philippine Studies 30 (3): 334–376. http://www.philippinestudies.net/files/journals/1/articles/1696/public/1696-3504-1-PB.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 William Henry Scott (1994). Barangay. Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 9715501389. https://archive.org/details/BarangaySixteenthCenturyPhilippineCultureAndSociety.

- ↑ Aurora Roxas-Lim. "Traditional Boatbuilding and Philippine Maritime Culture". International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region, UNESCO. http://ichcap.org/eng/ek/sub3/pdf_file/domain5/091_Traditional_Boatbuilding_and_Philippine_Maritime_Culture.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Patricia Calzo Vega (June 1, 2011). "The World of Amaya: Unleashing the Karakoa". GMA News Online. http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/scitech/content/222283/the-world-of-amaya-unleashing-the-karakoa/story/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Emma Helen Blair & James Alexander Robertson, ed (1906). The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/15157/pg15157-images.html.

- ↑ Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola (1711). "The Discovery and Conquest of the Molucco and Philippine Islands.". in John Stevens. A New Collection of Voyages and Travels, into several Parts of the World, none of them ever before Printed in English. p. 61. https://archive.org/stream/anewcollectionv00collgoog#page/n12/mode/2up.

- ↑ Francisco Combés (1667). Historia de las islas de Mindanao, Iolo y sus adyacentes : progressos de la religion y armas Catolicas. http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000014686.

- ↑ Antonio T. Carpio. "Historical Facts, Historical Lies, and Historical Rights in The West Philippine Sea". Institute for Maritime and Ocean Affairs. pp. 8, 9. http://www.imoa.ph/imoawebexhibit/Splices/.

- ↑ James Francis Warren (2007). The Sulu Zone, 1768-1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State. NUS Press. pp. 257–258. ISBN 9789971693862.

|

Categories: [Naval sailing ship types] [Tall ships]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 05/28/2025 07:56:09 | 3 views

☰ Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Engineering:Karakoa | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

.jpg)

KSF

KSF