Gettysburg Address

From Nwe

From Nwe

The Gettysburg Address is the most famous speech of U. S. President Abraham Lincoln and one of the most quoted speeches in United States history. It was delivered at the dedication of the Soldiers' National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on November 19, 1863, during the American Civil War, four and a half months after the Battle of Gettysburg. Of the 165,000 soldiers present at the battle, 45,000 suffered casualties—among them more than 7,500 dead. The battle turned the tide of the war irrevocably toward the Union side.

Lincoln's carefully crafted address, secondary to other presentations that day, shines brightly in history while the other speeches have long been forgotten. In fewer than three hundred words delivered over two to three minutes, Lincoln invoked the principles of human equality espoused by the Declaration of Independence and redefined the Civil War as a struggle not merely for the Union, but as "a new birth of freedom" that would bring true equality to all of its citizens.

Beginning with the now-iconic phrase "Four score and seven years ago," Lincoln referred to the events of the American Revolutionary War and described the ceremony at Gettysburg as an opportunity not only to dedicate the grounds of a cemetery, but also to consecrate the living in the struggle to ensure that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth." Despite the speech's prominent place in the history and popular culture of the United States, the exact wording of the speech is disputed. The five known manuscripts of the Gettysburg Address differ in a number of details and also differ from contemporary newspaper reprints of the speech.

Background

The Battle of Gettysburg (July 1-3, 1863) forever changed the little town of Gettysburg. The battlefield contained the bodies of more than 7,500 dead soldiers and several thousand horses of the Union's Army of the Potomac and the Confederacy's Army of Northern Virginia. The stench of rotting bodies made many townspeople violently ill in the weeks following the battle, and the burial of the dead in a dignified and orderly manner became a high priority for the few thousand residents of Gettysburg. Under the direction of David Wills, a wealthy 32-year-old attorney, Pennsylvania purchased 17 acres (69,000 m²) for a cemetery to honor those lost in the summer's battle.

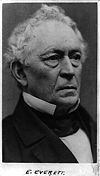

Wills originally planned to dedicate this new cemetery on Wednesday, September 23, and invited Edward Everett, who had served as secretary of state, U.S. Senator, U.S. Representative, governor of Massachusetts, and president of Harvard University, to be the main speaker. At that time Everett was widely considered to be the nation's greatest orator. In reply, Everett told Wills and his organizing committee that he would be unable to prepare an appropriate speech in such a short period of time, and requested that the date be postponed. The committee agreed, and the dedication was postponed until Thursday, November 19.

Almost as an afterthought, Wills and the event committee invited Lincoln to participate in the ceremony. Wills's letter stated, "It is the desire that, after the Oration, you, as Chief Executive of the nation, formally set apart these grounds to their sacred use by a few appropriate remarks."[1] Lincoln's role in the event was secondary, akin to the modern tradition of inviting a noted public figure to do a ribbon-cutting at a grand opening.[1]

Lincoln arrived by train in Gettysburg on November 18, and spent the night as a guest in Wills's house on the Gettysburg town square, where he put the finishing touches on the speech he had written in Washington.[2] Contrary to popular myth, Lincoln neither completed his address while on the train nor wrote it on the back of an envelope.[3] On the morning of November 19 at 9:30 A.M., Lincoln joined in a procession astride a chestnut bay horse, between Secretary of State William H. Seward and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase with the assembled dignitaries, townspeople, and widows marching out to the grounds to be dedicated. [4][5]

Approximately 15,000 people are estimated to have attended the ceremony, including the sitting governors of six of the 24 Union states: Andrew Gregg Curtin of Pennsylvania, Augustus Bradford of Maryland, Oliver P. Morton of Indiana, Horatio Seymour of New York, Joel Parker of New Jersey, and David Tod of Ohio.[6] The precise location of the program within the grounds of the cemetery is disputed.[7] Reinterment of the bodies buried from field graves into the cemetery, which had begun within months of the battle, was less than half complete on the day of the ceremony.[8]

Program and Everett's "Gettysburg Oration"

The program organized for that day by Wills and his committee included:

- Music, by Birgfield's Band

- Prayer, by Reverend T.H. Stockton, D.D.

- Music, by the Marine Band

- Oration, by Hon. Edward Everett

- Music, Hymn composed by B.B. French, Esq.

- Dedicatory Remarks, by the President of the United States

- Dirge, sung by Choir selected for the occasion

- Benediction, by Reverend H.L. Baugher, D.D. [1]

What was regarded as the "Gettysburg Address" that day was not the short speech delivered by President Lincoln, but rather Everett's two-hour oration. Everett's now seldom-read 13,607-word speech began:

- Standing beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature. But the duty to which you have called me must be performed; — grant me, I pray you, your indulgence and your sympathy.[9]

And ended two hours later with:

- But they, I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country, there will be no brighter page than that which relates the Battles of Gettysburg.[9]

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address

Not long after those well-received remarks, Lincoln spoke in his high-pitched Kentucky accent for two or three minutes. Lincoln's "few appropriate remarks" summarized the war in ten sentences and 272 words, rededicating the nation to the war effort and to the ideal that no soldier at Gettysburg had died in vain.

Despite the historical significance of Lincoln's speech, modern scholars disagree as to its exact wording, and contemporary transcriptions published in newspaper accounts of the event and even handwritten copies by Lincoln himself differ in their wording, punctuation, and structure. Of these versions, the Bliss version has become the standard text. It is the only version to which Lincoln affixed his signature, and the last he is known to have written.

The five manuscripts

The five known manuscript copies of the Gettysburg Address are each named for the associated person who received it from Lincoln. Lincoln gave a copy to each of his private secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay. Both of these drafts were written around the time of his November 19 address, while the other three copies of the address, the Everett, Bancroft, and Bliss copies, were written by Lincoln for charitable purposes well after November 19. In part because Lincoln provided a title and signed and dated the Bliss Copy, it has been used as the source for most facsimile reproductions of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address.

The two earliest drafts of the Address are subject to some confusion and controversy concerning their existence and provenance. Nicolay and Hay were appointed custodians of Lincoln's papers by Lincoln's son Robert Todd Lincoln in 1874.[3]

After appearing in facsimile in an article written by John Nicolay in 1894, the Nicolay copy was presumably among the papers passed to Hay by Nicolay's daughter, Helen, upon Nicolay's death in 1901. Robert Lincoln began a search for the original copy in 1908, which spurred Helen to spend several unsuccessful years searching for Nicolay's copy. In a letter to Lincoln, Helen Nicolay stated, "Mr. Hay told me shortly after the transfer was made that your father gave my father the original ms. of the Gettysburg Address."[3] Lincoln's search resulted in the discovery of a handwritten copy of the Gettysburg Address among the bound papers of John Hay—a copy now known as the "Hay Draft," which differed from the version published by John Nicolay in 1894 in numerous respects—the paper used, number of words per line, number of lines, and editorial revisions in Lincoln's hand.[3]

It was not until eight years later—in March 1916—that the manuscript known as the "Nicolay Copy," consistent with both the recollections of Helen Nicolay and the article written by her father, was reported to be in the possession of Alice Hay Wadsworth, John Hay's granddaughter.

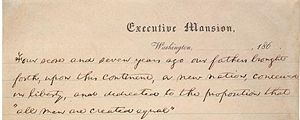

Nicolay Copy

The Nicolay Copy[10] is often called the "first draft" because it is believed to be the earliest extant copy. Scholars disagree over whether the Nicolay copy was actually the reading copy Lincoln used at Gettysburg on November 19. In an 1894 article that included a facsimile of this copy, Nicolay, who had become the custodian of Lincoln's papers, wrote that Lincoln had brought to Gettysburg the first part of the speech written in ink on Executive Mansion stationery, and that he had written the second page in pencil on lined paper before the dedication on November 19.[11]

Matching folds are still evident on the two pages, suggesting it could be the copy that eyewitnesses say Lincoln took from his coat pocket and read at the ceremony. Others believe that the delivery text has been lost, because some of the words and phrases of the Nicolay copy do not match contemporary transcriptions of Lincoln's original speech. The words "under God," for example, are missing in this copy from the phrase "that this nation (under God) shall have a new birth of freedom…" In order for the Nicolay draft to have been the reading copy, either the contemporary transcriptions were inaccurate, or Lincoln uncharacteristically would have had to depart from his written text in several instances. This copy of the Gettysburg Address apparently remained in John Nicolay's possession until his death in 1901, when it passed to his friend and colleague, John Hay, and after years of being lost to the public, it was reported found in March 1916. The Nicolay copy is on permanent display as part of the American Treasures exhibition of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.[12]

Hay Copy

With its existence first announced to the public in 1906, the Hay Copy[13] was described by historian Garry Wills as "the most inexplicable of the five copies Lincoln made." With numerous omissions and inserts, this copy strongly suggests a text that was copied hastily, especially when one examines the fact that many of these omissions were critical to the basic meaning of the sentence, not simply words that would be added by Lincoln to strengthen or clarify their meaning. This copy, which is sometimes referred to as the "second draft," was made either on the morning of its delivery, or shortly after Lincoln's return to Washington. Those who believe that it was completed on the morning of his address point to the fact that it contains certain phrases that are not in the first draft but are in the reports of the address as delivered as well as subsequent copies made by Lincoln. Some assert, as stated in the explanatory note accompanying the original copies of the first and second drafts in the Library of Congress, that it was this second draft which Lincoln held in his hand when he delivered the address.[14] Lincoln eventually gave this copy to his other personal secretary, John Hay, whose descendants donated both it and the Nicolay copy to the Library of Congress in 1916.

Everett Copy

The Everett Copy,[15] also known as the "Everett-Keyes" copy, was sent by President Lincoln to Edward Everett in early 1864, at Everett's request. Everett was collecting the speeches given at the Gettysburg dedication into one bound volume to sell for the benefit of stricken soldiers at New York's Sanitary Commission Fair. The draft Lincoln sent became the third autograph copy, and is now in the possession of the Illinois State Historical Library in Springfield, Illinois, where it is currently on display in the Treasures Gallery of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

Bancroft Copy

The Bancroft Copy of the Gettysburg Address was written out by President Lincoln in April 1864 at the request of George Bancroft, the most famous historian of his day.[16] Bancroft planned to include this copy in Autograph Leaves of Our Country's Authors, which he planned to sell at a Soldiers' and Sailors' Sanitary Fair in Baltimore, Maryland. As this fourth copy was written on both sides of the paper, it proved unusable for this purpose, and Bancroft was allowed to keep it. This manuscript is the only one accompanied by a letter from Lincoln, transmitting the manuscript, and by the original envelope, addressed and franked (i.e., signed for free postage) by Lincoln. This copy remained in the Bancroft family for many years until it was donated to the Carl A. Kroch Library at Cornell University.[14] It is the only one of the five copies to be privately owned.[17]

Bliss Copy

Discovering that his fourth written copy (which was intended for George Bancroft's Autograph Leaves) could not be used, Lincoln wrote a fifth draft, which was accepted for the purpose requested. The Bliss Copy,[18] once owned by the family of Colonel Alexander Bliss, Bancroft's stepson and publisher of Autograph Leaves, is the only draft to which Lincoln affixed his signature. It is likely this was the last copy written by Lincoln, and because of the apparent care in its preparation, and in part because Lincoln provided a title and signed and dated this copy, it has become the standard version of the address. The Bliss Copy has been the source for most facsimile reproductions of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. This draft now hangs in the Lincoln Room of the White House, a gift of Oscar B. Cintas, former Cuban Ambassador to the United States.[14] Cintas, a wealthy collector of art and manuscripts, purchased the Bliss copy at a public auction in 1949 for $54,000; at that time, it was the highest price ever paid for a document at public auction.[19]

Garry Wills, who won the 1993 Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction for his book, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, concluded the Bliss Copy "is stylistically preferable to others in one significant way: Lincoln removed 'here' from 'that cause for which they (here) gave…' The seventh 'here' is in all other versions of the speech." Wills noted the fact that Lincoln "was still making such improvements," suggesting Lincoln was more concerned with a perfected text than with an 'original' one.

Contemporary sources and reaction

Eyewitness reports vary as to their view of Lincoln's performance. In 1931, the printed recollections of 87-year-old Mrs. Sarah A. Cooke Myers, who was present, suggest a dignified silence followed Lincoln's speech: "I was close to the President and heard all of the Address, but it seemed short. Then there was an impressive silence like our Menallen Friends Meeting. There was no applause when he stopped speaking."[20]

According to historian Shelby Foote, after Lincoln's presentation, the applause was delayed, scattered, and "barely polite." [21] In contrast, Pennsylvania Governor Curtin maintained, "He pronounced that speech in a voice that all the multitude heard. The crowd was hushed into silence because the President stood before them...It was so Impressive! It was the common remark of everybody. Such a speech, as they said it was!"[22]

In a letter to Lincoln written the following day, Everett praised the president for his eloquent and concise speech, saying, "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes." Lincoln was glad to know the speech was not a "total failure."

Other public reaction to the speech was divided along partisan lines. The next day the Chicago Times observed, "The cheek of every American must tingle with shame as he reads the silly, flat and dishwatery ["hackneyed"] utterances of the man who has to be pointed out to intelligent foreigners as the President of the United States." In contrast, the New York Times was complimentary. A Massachusetts paper printed the entire speech, commenting that it was "deep in feeling, compact in thought and expression, and tasteful and elegant in every word and comma."

Lincoln himself, over time, revised his opinion of "my little speech."

Audio recollections of an eyewitness

William R. Rathvon is the only known eyewitness of both Lincoln's arrival at Gettysburg and the address itself to have left an audio recording of his recollections. Rathvon spent his summers in Gettysburg. During the battle, his grandmother's home was briefly used as a headquarters for Confederate general Richard Ewell. She also provided temporary refuge to Union soldiers who were running from the pursuing Confederates. [23]

Rathvon was nine years old when he and his family personally saw Lincoln speak at Gettysburg. One year before his death in 1939, Rathvon's reminiscences were recorded on February 12, 1938, at the Boston studios of radio station WRUL, including his reading the address itself. A 78-r.p.m. record of Rathvon’s comments was pressed, and the title of the record was "I Heard Lincoln That Day - William R. Rathvon, TR Productions."

A copy wound up at National Public Radio during a "Quest for Sound" project in the 1990s. NPR continues to air them around Lincoln's birthday. To listen to a 6-minute NPR-edited recording, click here and for the full 21-minute recording, click here. Even after almost 70 years, Rathvon's audio recollections remain a moving testimony to Lincoln's transcendent effect on his fellow countrymen and the affection that so many ardent unionists felt for him in his day.

Themes and textual analysis

Lincoln used the word "nation" five times (four times when he referred to the American nation, and one time when he referred to "any nation so conceived and so dedicated"), but never the word "union," which might refer only to the North—furthermore, restoring the nation, not a union of sovereign states, was paramount to his intention. Lincoln's text referred to the year 1776 and the American Revolutionary War, and included the famous words of the Declaration of Independence, that "all men are created equal."

Lincoln did not allude to the 1789 Constitution, which implicitly recognized slavery in the "three-fifths compromise," and he avoided using the word "slavery." He also made no mention of the contentious antebellum political issues of nullification or state's rights.

In Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America, Garry Wills suggests the Address was influenced by the American Greek Revival and the classical funereal oratory of Athens, as well as the transcendentalism of Unitarian minister and abolitionist Theodore Parker (the source of the phrase "of all the people, by all the people, for all the people") and the constitutional arguments of Daniel Webster.[24]

Author and Civil War scholar James McPherson's review of Wills' book addresses the parallels to Pericles' funeral oration during the Peloponnesian War as described by Thucydides, and enumerates several striking comparisons with Lincoln's speech.[25] Pericles' speech, like Lincoln's, begins with an acknowledgment of revered predecessors: "I shall begin with our ancestors: it is both just and proper that they should have the honour of the first mention on an occasion like the present"; then praises the uniqueness of the State's commitment to democracy: "If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences"; honors the sacrifice of the slain, "Thus choosing to die resisting, rather than to live submitting, they fled only from dishonour, but met danger face to face"; and exhorts the living to continue the struggle: "You, their survivors, must determine to have as unfaltering a resolution in the field, though you may pray that it may have a happier issue."[26][27]

Craig R. Smith, in "Criticism of Political Rhetoric and Disciplinary Integrity," also suggested the influence of Webster's famous speeches on the view of government expressed by Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address, specifically, Webster's "Second Reply to Hayne," in which he states, "This government, Sir, is the independent offspring of the popular will. It is not the creature of State legislatures; nay, more, if the whole truth must be told, the people brought it into existence, established it, and have hitherto supported it, for the very purpose, amongst others, of imposing certain salutary restraints on State sovereignties."[28][29]

Some have noted Lincoln's usage of the imagery of birth, life, and death in reference to a nation "brought forth," "conceived," and that shall not "perish." Others, including author Allen C. Guelzo, suggested that Lincoln's formulation "four score and seven" was an allusion to the King James Bible's Psalms 90:10, in which man's lifespan is given as "threescore years and ten." [30][31]

Writer H. L. Mencken criticized what he believed to be Lincoln's central argument, that Union soldiers at Gettysburg "sacrificed their lives to the cause of self-determination." Mencken contended, "It is difficult to imagine anything more untrue. The Union soldiers in the battle actually fought against self-determination; it was the Confederates who fought for the right of their people to govern themselves."[32] Certainly, however, one can point out the obvious difference between the right of personal self-determination and the right of communal self-governance. Arguably, the Union soldiers fought for the former, while the Confederates fought for the latter.

Myths and trivia

In an oft-repeated legend, after completing the speech, Lincoln turned to his bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon and remarked that his speech, like a bad plow, "won't scour." According to Garry Wills, this statement has no basis in fact and largely originates from the unreliable recollections of Lamon.[1] In Wills' view, "[Lincoln] had done what he wanted to do [at Gettysburg]."

Another persistent myth is that Lincoln composed the speech while riding on the train from Washington to Gettysburg and wrote it on the back of an envelope, a story at odds with the existence of several early drafts and the reports of Lincoln's final editing while a guest of David Wills in Gettysburg.[33]

Another myth is that the assembled at Gettysburg expected Lincoln to speak much longer than he did. Everyone there knew (or should have known) that the President's role was minor. The only known photograph of Lincoln at Gettysburg, taken by photographer David Bachrach[34] was identified in the Mathew Brady collection of photographic plates in the National Archives and Records Administration in 1952. While Lincoln's speech was short and may have precluded multiple pictures of him while speaking, he and the other dignitaries sat for hours during the rest of the program. However, given the length of Everett's speech and the length of time it took for nineteenth-century photographers to get "set up" before taking a picture, it's quite plausible that the photographer themselves were ill prepared for the brevity of Lincoln's remarks.

The copies of the Address within the Library of Congress are encased in specially-designed, temperature-controlled, sealed containers with argon gas in order to protect the documents from oxidation and further degeneration.[35]

In popular culture

The importance of the Gettysburg Address in the history of the United States is underscored by its enduring presence in American culture. In addition to its prominent place carved into stone on the south wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the Gettysburg Address is frequently referred to in works of popular culture, with the implicit expectation that contemporary audiences will be familiar with Lincoln's words.

Martin Luther King, Jr., began his "I Have a Dream" speech, itself one of the most-recognized speeches in American history, with a reference to Lincoln and an allusion to Lincoln's words: "Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation."

Some examples of its treatment in popular culture include Meredith Willson's 1957 musical, The Music Man, in which the Mayor of River City consistently begins speaking with the words "Four score . . ." until his actual speech is handed to him. In the 1967 musical Hair, a song called "Abie Baby/Fourscore" refers to Lincoln's assassination, and contains portions of the Gettysburg Address delivered in an ironic manner.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 pp. 24-5, p. 35, pp. 34-5, p. 36, Wills, Garry (1992). Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words That Remade America. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-76956-1.

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln in the Wills House Bedroom at Gettysburg.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Johnson, Martin P. (Summer 2003). Who Stole the Gettysburg Address. Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 24 (2): 1–19.

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln at the Gettysburg Town Square. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ Saddle Used by Abraham Lincoln in Gettysburg.

- ↑ The New York Times, November 20, 1863.

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg Cemetery. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ getaddinfo. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Edward Everett's complete "Gettysburg Oration". Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ Library of Congress website, Nicolay Copy, page 1, page 2

- ↑ Nicolay, J. "Lincoln's Gettysburg Address," Century Magazine 47 (February 1894): 596–608, cited by Johnson, Martin P. "Who Stole the Gettysburg Address," Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 24 (2) (Summer 2003): 1-19.

- ↑ Library of Congress website, Top Treasures of the American Treasures exhibition

- ↑ Library of Congress website, Hay Copy, page 1, page 2

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Gettysburg National Military Park Historical Handbook website, http://www.pueblo.gsa.gov/cic_text/misc/gettysburg/g2.htm GNMP website]

- ↑ Virtual Gettysburg website, Everett Copy

- ↑ Cornell University Library website, Bancroft Copy, page 1, page 2

- ↑ The Cornell Daily Sun - C.U. Holds Gettysburg Address Manuscript. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ Illinois Historic Preservation Agency website, Bliss Copy, page 1, page 2, page 3

- ↑ Oscar B. Cintas foundation website.. Retrieved 2005-12-23.

- ↑ Recollections of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ Foote, Shelby (1958). The Civil War, A Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian. Random House. ISBN 0-394-49517-9.

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg Cemetery (See above). Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ 21 Minute audio recording of William R. Rathvon's audio recollections of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address recorded in 1938. Retrieved 2006-05-02.

- ↑ Vosmeier, Matthew Noah. Lincoln Lore: Gary Wills' Lincoln at Gettysburg. The Lincoln Museum, Fort Wayne, Indiana. Retrieved December 16, 2005.

- ↑ McPherson, James (July 16, 1992). The Art of Abraham Lincoln. The New York Review of Books 39 (13).

- ↑ Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified.

- ↑ The New York Review of Books: The Art of Abraham Lincoln. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ ACJ Special:Smith. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified.

- ↑ H-Net Review: Daniel J. McInerney. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ Guelzo, Allen C. (1999). Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President. Grand Rapids, M.I.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0802838723.

- ↑ Note on the Gettysburg Address. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

- ↑ Lincoln urban legends debunked.

- ↑ History of Bachrach photography studio. Retrieved 2005-12-19.

- ↑ Preservation of the drafts of the Gettysburg Address at the Library of Congress. Retrieved 2005-12-18.

External links

All links retrieved June 21, 2017.

- Carl A. Kroch library Division of Rare & Manuscript Collections, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY

- Gettysburg National Military Park (GNMP) Gettysburg Historical Handbook

- Readings of the Gettysburg Address: Actors Sam Waterston and Jeff Daniels; musician Johnny Cash.

- Website of National Public Radio with Waterston reading.

- Contemporary newspaper reactions cited at Cornell University Library exhibit.

- William V. Rathvon's eyewitness audio recollections and reading of the address at NPR.org (6-minute version)

- William V. Rathvon's eyewitness audio recollections and reading of the address at NPR.org full 21-minute recording

- Our Documents: A National Initiative on American History, Civics, and Service

- The Annenberg/CPB Channel

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:26:03 | 16 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gettysburg_Address | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF