Gospel Of John

From Nwe

From Nwe

| A series of articles on |

"John" in the Bible |

Johannine literature |

Names |

Communities |

Related Literature |

| New Testament |

|---|

The Gospel of John, (literally, According to John; Greek, Κατά Ιωαννην, Kata Iōannēn) is the fourth gospel in the canon of the New Testament, traditionally ascribed to John the Evangelist. Like the three synoptic gospels, it contains an account of some of the actions and sayings of Jesus, but differs from them in narrative structure, ethos and theological emphases. The purpose is expressed in the conclusion, 20:30-31: "… these Miracles of Jesus are written that you may (come to) believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through this belief you may have life in his name.[1]

Of the four gospels, John is the only one that presents a true christology, describing him as the Logos (Word) who existed from the beginning, teaching at length about his identity as the only savior, and (according to the trinitarian tradition) declaring him to be God.[2]

Compared to the Synoptic Gospels, John focuses on Jesus' "cosmic mission" to redeem humanity. Only in John does Jesus engage in long discourses about his role; John also includes a substantial amount of material that Jesus shared with the disciples only. Certain elements of the synoptics (such as parables, exorcisms, and the Second Coming) are not found in John.

Since the "higher criticism" of the nineteenth century, historians have largely rejected the gospel of John as a reliable source of information about the historical Jesus.[3][4] "[M]ost commentators regard the work as anonymous."[5]

Narrative summary (structure and content of John)

After the prologue (1:1-5), the narrative of the gospel begins with verse 6, and consists of two parts. The first part (1:6-ch. 12) relates Jesus' public ministry from the time of his baptism by John the Baptist to its close. In this first part, John emphasizes seven of Jesus' miracles, refering to them as "signs." The second part (ch. 13-21) presents Jesus in dialogue with his immediate followers (13-17) and gives an account of his Passion and Crucifixion and of his appearances to the disciples after his Resurrection (18-20). Raymond E. Brown, a scholar of the Johannine community, labelled the first and second parts the "Book of Signs" and the "Book of Glory," respectively.[6] In Chapter 21, the "appendix," Jesus restores Peter after his denial, predicts Peter's death, and discusses the death of the "beloved disciple."

The major events covered by the Gospel of John include:

Hymn to the Word

Book of Signs, Seven Signs

|

Book of Glory, Last Teachings and Death

|

Date and authorship

Authorship

The authorship has been disputed since at least the second century, with mainstream Christianity believing that the author is John the Apostle, son of Zebedee. Modern experts usually consider the author to be an unknown non-eyewitness from the early second century, though many apologetic Christian scholars still hold to the conservative Johannine view that ascribes authorship to John the Apostle.

The text itself is unclear about the issue. John 21:20-25 contains information that could be construed as autobiographical. Conservative scholars generally assume that first person "I" in verse 25, the disciple in verse 24 and the disciple whom Jesus loved (also known as the Beloved Disciple in verse 20 are the same person;[7][8] they further identify all three descriptors with the Apostle John through a combination of external and internal evidence.[9] Critics point out that the abrupt shift from third person to first person in vss. 24-25 indicates that the author of the epilogue, who is supposed a third-party editor, claims the preceding narrative is based on the Beloved Disciple's testimony, while he himself is not the Beloved Disciple.[10][11]

Ancient testimony is similarly conflicted. Attestation of Johannine authorship can be found as early as Irenaeus.[12] Eusebius wrote that Irenaeus received his information from Polycarp, who is said to have received it from the Apostles directly.[13] Charles E. Hill argues that there is a solid early orthodox tradition of authorship: the tradition that an apostle of Jesus wrote the Gospel and can be attested to as early as the first two decades of the second century, and there are many Church Fathers in the remainder of the second century that ascribe the text to John the Evangelist.[14] Martin Hengel and Jorge Frey similarly argue for John the Presbyter as the author of the text. Hill goes on to propose that Ignatius, Polycarp, Papias’ elders, and Hierapolis' Exegesis of the Lord’s Oracles possibly all quote from the Gospel of John.

Epiphanius, however, takes note of an Early Christian sect, the Alogi, who believed the Gospel was actually written by one Cerinthus, a second-century Gnostic.[15]. Corroborating this evidence is a quotation by Eusebius of Caesarea (History of the Church 7.25.2) in which Dionysius of Alexandria (mid-third century) claims that the Apocalypse of John (known commonly as the Book of Revelation), but not the Gospel of John, was believed by some before him (7.25.1) to also have been written by Cerinthus. This discussion of the Alogi represents the only instance in which both the Book of Revelation and the Gospel of John were specifically attributed to Cerinthus.[16] Hill asserts that, at that time, the Gospel of John was never attributed to Cerinthus by the established orthodoxy; that Eusebius was only stating a theory that he had heard; and that Eusebius himself believed the Gospel to have been written by the Apostle John.[17]

Starting in the nineteenth century, critical scholarship has further questioned the apostle John's authorship, arguing that the work was written decades after the events it describes. The critical scholarship argues that there are differences in the composition of the Greek within the Gospel, such as breaks and inconsistencies in sequence, repetitions in the discourse, as well as passages that clearly do not belong to their context, and these suggest redaction.[18]

Raymond E. Brown, a biblical scholar who specialized in studying the Johannine community, summarizes a prevalent theory regarding the development of this gospel.[19] He identifies three layers of text in the Fourth Gospel (a situation that is paralleled by the synoptic gospels): 1) an initial version Brown considers based on personal experience of Jesus; 2) a structured literary creation by the evangelist which draws upon additional sources; and 3) the edited version that readers know today (Brown 1979).

Date

Most scholars date the gospel c. 90-100 C.E., though dates as early as the 60s or as late as the 140s have been advanced by a small number of scholars. Justin Martyr quoted from the gospel of John, which would also support that the Gospel was in existence by at least the middle of the second century.[20]

The traditional view is supported by the statement of Clement of Alexandria that John wrote to supplement the accounts found in the other gospels (Eusibius, Ecclesiastical History, 6.14.7), although this statement in part addressed its difference from the synoptic gospels. If true, this would place the writing of John's gospel sufficiently after the writing of the synoptics.

Conservative scholars consider internal evidences, such as the lack of the mention of the destruction of the temple and a number of passages that they consider characteristic of an eye-witness (John 13:23ff, 18:10, 18:15, 19:26-27, 19:34, 20:8, 20:24-29), sufficient evidence that the gospel was composed before 100 and perhaps as early as 50-70. Barrett suggests an earliest date of 90, based on familiarity with Mark’s gospel, and the late date of a synagogue expulsion of Christians (which is a theme in John).[21] Morris suggests 70, given Qumran parallels and John’s turns of phrase, such as "his disciples" vs. "the disciples".[22] John A. T. Robinson proposes an initial edition by 50-55 and then a final edition by 65 due to narrative similarities with Paul.[23]

There are critical scholars who are of the opinion that John was composed in stages (probably two or three), beginning at an unknown time (50-70?) and culminating in a final text around 95-100. This date is assumed in large part because John 21, the so-called "appendix" to John, is largely concerned with explaining the death of the "beloved disciple," supposedly the leader of the Johannine community that would have produced the text. If this leader had been a follower of Jesus, or, more likely, a disciple of one of Jesus' followers, then a death around 90-100 is possible.

Manuscripts

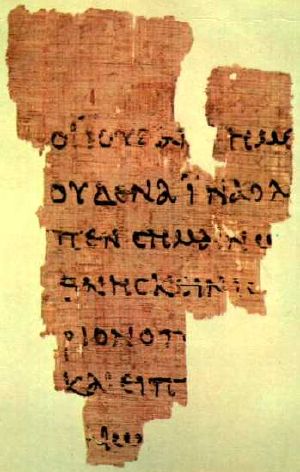

- Further information: Rylands Library Papyrus P52, and Papyrus 66

The earliest known manuscripts of the New Testament is a fragment from John, P52. A scrap of papyrus roughly the size of a business card discovered in Egypt in 1920 (now at the John Rylands Library, Manchester, accession number P52) bears parts of John 18:31-33 on one side and John 18:37-38 on the other. Most texts list the date of this manuscript to c. 125.[24] [25] The difficulty of fixing the date of a fragment based solely on paleographic evidence allows for a range of dates that extends from before 100 to well into the second half of the second century. P52 is small, and although a plausible reconstruction can be attempted for most of the fourteen lines represented, nevertheless the proportion of the text of the Gospel of John for which it provides a direct witness is necessarily limited, so it is rarely cited in textual debate.[26]

Sources

- Further information: Source criticism

In 1941 Rudolf Bultmann suggested[27] that the author of John depended in part on an oral miracles tradition or manuscript account of Christ's miracles that was independent of, and not used by, the synoptic gospels. This hypothetical "Signs Gospel" is alleged to have been circulating before 70. Its traces can be seen in the remnants of a numbering system associated with some of the miracles that appear in the Gospel of John: all of the miracles that are mentioned only by John occur in the presence of John; the "signs" or semeia (the expression is uniquely John's) are unusually dramatic; and they are accomplished in order to call forth faith (see John 12:37). These miracles are different both from the rest of the "signs" in John, and from the miracles in the synoptic gospels, which occur as a result of faith. Bultmann's conclusion that John was reinterpreting an early Hellenistic tradition of Jesus as a wonder-worker, a "magician" within the Hellenistic world-view, was so controversial that heresy proceedings were instituted against him and his writings. (See more detailed discussions linked below.)

The mysterious Egerton Gospel appears to represent a parallel but independent tradition to the Gospel of John. According to scholar Ronald Cameron, it was originally composed some time between the middle of the first century and early in the second century, and it was probably written shortly before the Gospel of John.[28] Robert W. Funk, et al. places the Egerton fragments in the second century, perhaps as early as 125, which would make it as old as the oldest fragments of John.[29]

It is notable that the Gospel's opening prologue in John 1:1-18 consciously echoes the opening motif of Genesis, "In the beginning." Beyond this, there has been much debate over the centuries on the theological background of the prologue: is it a formula of Hellenistic rhetoric, traditional Jewish wisdom, or some type of Qumran-like Dead Sea scrolls metaphysic? Each view has its backers and detractors.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, the pendulum of scholarly opinion has swung back to a traditional Jewish background. While Genesis 1 focuses on God's creation, John 1 focuses on the Word (or Logos in the Greek) and the significance of the Word coming into the already created world.

One Christian tradition, held by a number of Christians today, is that the Gospel of John was not based on other written sources. Because they consider the author of John to be John the Apostle, they conclude that John actually experienced all the things he described. There are also Christian scholars, such as NT Wright and John Shelby Spong, who reject the conclusions of source criticism.

Popular Passages in the Gospel

"The truth shall make you free" - Jn 8:32 (KJV)

John 1:1 is often quoted as the boldest scriptural statement describing Jesus as the Word Incarnate: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." Since the Greek "Logos" can literally mean "word," but also, in a broader sense, "discourse" or "reason," it has been interpreted by prominent theologians (such as Pope Benedict XVI in his famous Regensburg lecture) as establishing that reason and logical thinking are, in essence, also aspects of the divine.

John 3:16 is one of if not the most widely known passages in the New Testament: "For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life."

Another popular passage from John is John 4:13-14. "Jesus said to her, 'Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again, but those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty. The water that I will give will become in them a spring of water gushing up to eternal life." Jesus had said this to a Samaritan woman whom he met at a well, and he told her about the living water that he offered. This saying was based partially on Isaiah 55:1-2.

One of the more popular passages from the Book of John is the story of the blind man: "Then again called they (the Pharisees) the man that was blind, and said unto him, Give God the praise:we know that this man (Jesus) is a sinner. He answered and said, Whether he be a sinner or no, I know not: one thing I know, that, whereas I was blind, now I see." John 24-25

John 10:34: "Jesus said to them, 'Is it not written in your law, "I say you are gods?"'" (quoting Psalm 82:6) is very popular.

Characteristics of the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John is easily distinguished from the three Synoptic Gospels, which share a considerable amount of text. John omits about 90 percent of the material in the synoptics.[30] The synoptics describe much more of Jesus' life, miracles, parables, and exorcisms. However, the materials unique to John are notable, especially in their effect on modern Christianity.

Christology

John portrays Jesus Christ as "a brief manifestation of the eternal Word, whose immortal spirit remains ever-present with the believing Christian."[31] The gospel gives far more focus to the mystical relation of the Son to the Father. Many have used his gospel for the development of the concept of the Trinity while the Synoptic Gospels focused more on Jesus' life and less directly on theological concepts, such as Jesus as the Son of God. The gospel also focuses on the relation of the Redeemer to believers, the announcement of the Holy Spirit as the Comforter (Greek Paraclete), and the prominence of love as an element in the Christian character.

Jews

The Gospel’s treatment of the role of the Jewish authorities in the Crucifixion has given rise to allegations of anti-Semitism. The Gospel often employs the title "the Jews" when discussing the opponents of Jesus. The meaning of this usage has been the subject of debate, though critics of the “anti-Semitic” theory cite that the author most likely considered himself Jewish and was probably speaking to a largely Jewish community. Hence some argue that "the Jews" properly refers to the Jewish religious authorities (see: Sanhedrin), and not the Jewish people as a whole. It is because of this controversy that some modern English translations, such as Today's New International Version, remove the term "Jews" and replace it with more specific terms to avoid anti-Semitic connotations, citing the above argument. Most critics of these translations, conceding this point, argue that the context (since it is obvious that Jesus, John himself, and the other disciples were all Jews) makes John's true meaning sufficiently clear, and that a literal translation is preferred.

It is more generally pointed to as evidence for a later date of authorship, at a time when the Christian community had already been removed from the synagogue and were considered by Jewish authorities as a separate sect, one that defined itself in opposition to the synagogue traditions.

Gnostic elements

Though not commonly understood as Gnostic, John has elements in common with Gnosticism.[30] Gnostics must have read John because it is found with Gnostic texts. The root of Gnosticism is that salvation comes from gnosis, secret knowledge. The nearly five chapters of the "farewell discourses" (John 13, 18) Jesus shares only with the Twelve Apostles. Jesus pre-exists birth as the Word (Logos). This origin and action resemble a gnostic aeon (emanation from God) being sent from the pleroma (region of light) to give humans the knowledge they need to ascend to the pleroma themselves. John's denigration of the flesh, as opposed to the spirit, is a classic Gnostic theme.[30]

It has been suggested that similarities between John's Gospel and Gnosticism may spring from common roots in Jewish Apocalyptic literature.[32]

No parousia

The gospel contains "no explicit reference to the parousia (second coming)," and some scholars have suggested that John portrays Jesus as having already "come again" in spirit.

Differences from the Synoptic Gospels

John is significantly different from the Synoptic Gospels in many ways. Some of the differences are:

- The Gospel of John contains 3 passover feasts, suggesting Jesus' ministry lasted between 2 and 3 years, where in the synoptic gospels, it is only one.

- The Kingdom of God is only mentioned twice in John (3:3-5). In contrast, the other gospels repeatedly use the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Heaven as important concepts. John's Jesus claims a kingdom of his own, not of this world: 18:36. See also New Covenant (theology).

- Technically, the Gospel of John does not contain any parables.[33] It does, however, contain metaphoric stories, such as The Shepherd and The Vine. Synoptic parables are poetic stories, each of which illustrates a single message or idea. John's metaphoric stories are allegories, in which each individual element corresponds to a specific group or thing. Medieval Bible exegetes sometimes assigned allegorical meanings to elements in synoptic parables, but modern scholars reject these interpretations.

John 10:1-5 is potentially a stand-alone parable of Jesus, which UBS calls "Parable of the Sheepfold," John 10:6 calls it a "figure of speech," Strong's G3942, however, John 10:7 states I am the gate, which makes it a metaphor.

- The saying "He who has ears, let him hear" is absent from John.

- The healings of demon-possessed people are never mentioned as in the Synoptics.

- The Synoptics contain a wealth of stories about Jesus' miracles and healings, but John does not have as many of those stories; John tends to elaborate more heavily on its stories than do the Synoptics.

- John's stories are interpreted as signs of Jesus' divinity rather than examples of his compassion.

- Major synoptic speeches of Jesus are absent, including all of the Sermon on the Mount and the Olivet discourse and the instructions that Jesus gave to his disciples when he sent them out throughout the country to heal and preach (as in Matthew 10 and Luke 10). Instead the major speeches according to John are at the Sea of Galilee 6:22-71, the temple 7:14-8:59, and the last supper 13-17.

- The narrative structure of the synoptics leads up to the Passover events in Jerusalem. In John the narrative structure moves back and forth between Jerusalem and Galilee. Thus events in Jerusalem which by necessity take place at the end of the synoptics are moved around within John's text. Jesus driving the money changers from the temple appears near the beginning of the work.

- Most of the action in John takes place in Iudaea Province and Jerusalem; only a few events occur in Galilee, and of those, only the feeding of the multitude (6:1-16) and the trip across the Sea of Galilee (6:17-21) are also found in the Synoptics.

- According to the New American Bible, (New York: Catholic Book Publishing Co., 1970) the story of the adulteress (John 8:1-11) is missing from the best early Greek manuscripts. When it does appear it is at different places: here, after (John 7:36) or at the end of this gospel. It can also be found at Luke Luke 21:38.

- The crucifixion of Jesus is recorded as Nisan 14 (19:14), about noon, in contrast to the synoptic Nisan 15.

- Jesus does not utter eschatological prophecies.[30]

Critical scholarship on the differences between John and the synoptics

Since the advent of critical scholarship, John's historical value has been considered less significant than the synoptic traditions. The scholars of the 19th century concluded that the Gospel of John had no historical value. Over the next two centuries scholars such as Bultmann and Dodd looked closer and began finding historically relevant sections of John. Some scholars today believe that parts of John represent an independent historical tradition from the synoptics, while other parts represent later traditions.[34] However, the scholars of the Jesus Seminar assert that there is little historical value in John, and consider nearly every Johannine saying of Jesus to be nonhistorical.[35].

Other characteristics unique to John

- The Apostle Thomas is given a personality beyond a mere name, as "Doubting Thomas" (John 20:27 etc).

- Jesus refers to himself with "εγω ειμι" "I am" seven times (John 6:35) (John 8:12) (John 10:9) (John 10:11) (John 11:25) (John 14:6) (John 15:1), beyond the common meaning, many see this as an allusion to Exodus 3:14 and thus a claim to divinity.

- In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus refuses to give any sign that he is the messiah, which is known as the Messianic Secret, for example Mark 8:11-12. In the Gospel of Matthew and Gospel of Luke, only the Sign of Jonah will be given (Matthew 12:38-39,16:1-4, Luke 11:29-30). The Gospel of John on the other hand has Jesus providing many signs, such as 2:11 and 2:18-19 and 12:37.

- Each "sign" corresponds to one of the metaphoric "εγω ειμι" "I am" sayings (John 6:1-11) (John 9:1-11) (John 5:2-9) (John 11:1-45) (John 4:46-54) (John 2:1-11) For example, the multiplication of bread corresponds to "I am the bread of life"

- Two "signs" are numbered (John 2:11) (John 4:54), cf. Mark 8:10–12.

- There are no stories about Satan, demons or exorcisms, no predictions of end times, though there is mention of the "Last Day" (6:39-40, 6:44, 6:54, 11:24, 12:48), no Sermon on the Mount, no ethical teachings such as the Expounding of the Law other than "Love one another" (13:31-35), or apocalyptic teachings other than perhaps 15:18-16:4.

- The hourly time is given: Greek text: about the tenth hour, translated as "four o'clock in the afternoon" [first hour is 6 a.m., sundial time] (John 1:39)

- When the water at the Pool of Bethesda is moved by an angel it heals (John 5:3-4)

- Jesus washes the disciples' feet (John 13:3-16)

- At Chapter 13 there is the description of the Last Supper but, unlike the Synoptic Gospels (Matt 26:26-29; Mark 14:22-26, Luke 22:14-20) there is no formal institution of the Eucharist, whereas the prediction of Judas' betrayal is amply reported (13:21-32). The Transubstantiation is mentioned earlier (6:48-71).

- No other women are mentioned going to the tomb with Mary Magdalene. (John 20:1)

- Mary Magdalene visits the empty tomb twice. She believes Jesus' body has been stolen. The second time she sees two angels. They do not tell her Jesus is risen. They only ask why she is crying. Mary mistakes Jesus for the gardener. He tells Mary not to touch or cling to him. (John 20:17). About a week later (some translations give "eight days later"), in the same chapter (John 20:28), Jesus asks Thomas to touch him and to place his fingers and hand in Jesus' still open wounds. At the sight of Jesus, Thomas gives an exclamation of faith but if he follows Jesus' direction, it is not in the text.

- Some of the brethren thought the "disciple whom Jesus loved" would not die, and an explanation is given for his death. (John 21:23)

- The "disciple whom Jesus loved" wrote down things he had witnessed, and his testimony is asserted by a third party to be true (John 21:24)

- The beloved disciple (traditionally believed to be the Apostle John) is never named.

- When speaking, prior to his message, Jesus says "verily" (John 5:24) (amen) twice, rather than just once in the Synoptic Gospels.

- Jesus carried his own cross (19:17); in the synoptics the cross was carried by Simon of Cyrene (Mark 15:21, Matthew 27:32, Luke 23:26).

Notes

- ↑ The New American Bible, published by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2002. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ A detailed technical discussion can be found in Raymond E. Brown's article: "Does the New Testament call Jesus God?" in Theological Studies 26 (1965): 545-573

- ↑ Leopold Fonck. Gospel of Saint John, in Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ "In particular, the fourth Gospel, which does not emanate or profess to emanate from the apostle John, cannot be taken as an historical authority in the ordinary meaning of the word. The author of it acted with sovereign freedom, transposed events and put them in a strange light, drew up the discourses himself, and illustrated 22 great thoughts by imaginary situations. Although, his work is not altogether devoid of a real, if scarcely recognizable, traditional element, it can hardly make any claim to be considered an authority for Jesus’ history; only little of what he says can be accepted, and that little with caution. On the other hand, it is an authority of the first rank for answering the question, What vivid views of Jesus’ person, what kind of light and warmth, did the Gospel disengage?" Adolf von Harnack, "What is Christianity?" Lectures Delivered in the University of Berlin during the Winter-Term 1899-1900. Lecture II. [1] Christian Classics Ethereal Library.Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ↑ Stephen L Harris. Understanding the Bible: a reader's introduction, 2nd ed. (Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985), 302.

- ↑ Studies in John Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ A Historical Introduction to the New Testament by Robert M. Grant Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ Exegetical Commentary on John 21 bible.org. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ The Gospel of John: Introduction, Argument, Outline bible.org. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ THE GOSPEL OF JOHN earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ Gospel of John earlychristianwritings.com. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ The Gospel of John: Introduction, Argument, Outline bible.org. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ The Gospel of John: Introduction, Argument, Outlinebible.org. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ Charles E. Hill. The Johannine Corpus in the Early Church. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 473

- ↑ Panarion 51.3.1-6

- ↑ Panarion 51.3.1-6

- ↑ Hill

- ↑ Bart D. Ehrman. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. (New York: Oxford, 2004), 164-165

- ↑ Raymond E. Brown Introduction to the New Testament. Anchor Bible New York 1997. ISBN 0-385-24767-2 363-364}}

- ↑ Justin Martyr NTCanon.org. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ↑ C. K. Barrett. The Gospel According to St. John. 127-128

- ↑ L. Morris. The Gospel According to John. 59

- ↑ J. A. T. Robinson.. Redating the Gospels, 284, 307

- ↑ Bruce M. Metzger. The text of the New Testament: its transmission, corruption, and restoration. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 56

- ↑ Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland. The Text of the New Testament an Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0802840981), 99

- ↑ Tuckett, 544; New Testament Manuscripts The Oldest New Testament.

- ↑ Rudolf Bultmann. Das Evangelium des Johannes. (1941). (translated as The Gospel of John: A Commentary. (1971)

- ↑ Ronald Cameron, (ed.) The Other Gospels: Non-Canonical Gospel Texts. (1982)

- ↑ Robert W. Funk, Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. (HarperSanFrancisco. 1993), 543.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Stephen L Harris. Understanding the Bible: a reader's introduction, 2nd ed. (Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985), 304. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "”Harris”" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHarris - ↑ Kovacs, Judith L. (1995). Now Shall the Ruler of This World Be Driven Out: Jesus’ Death as Cosmic Battle in John 12:20-36. Journal of Biblical Literature 114(2), 227-247.

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia: Parables: "There are no parables in St. John's Gospel." Retrieved October 29, 2007.

- ↑ Brown 1997, 362-364

- ↑ Jesus Seminar religioustolerance.org. Retrieved October 29, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aland, Kurt, and Barbara Aland. The Text of the New Testament an Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 0802840981

- Barrett, C. K. The Gospel According to St. John. S.P.C.K., 1960. ASIN B000O2IJ7U

- Bernard, John H. & A. H. McNeile. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary On The Gospel According To St. John. New York: C. Scribner' Sons, 1929. OCLC 755472

- Brown, Raymond E. The Community of the Beloved Disciple. Paulist Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0809121748

- Brown, Raymond E., "Does the New Testament call Jesus God?" in Theological Studies 26 (1965): 545-573

- Brown, Raymond E. The Gospel According to John. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1966-1970. ISBN 978-0385015172

- Brown, Raymond E. Introduction to the New Testament. New York: Anchor Bible, 1997. ISBN 0385247672

- Cameron, Ronald. (ed.) The Other Gospels: Non-Canonical Gospel Texts. 1982

- Ehrman, Bart D. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford, 2003. ISBN 0195154622

- Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco, 1993.

- Harris, Stephen L. Understanding the Bible: a reader's introduction, 2nd ed. Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985.

- Hill, Charles E. The Johannine Corpus in the Early Church. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0199291441

- Jensen, Robin M. "The Two Faces of Jesus," Bible Review (2002): 2. ISSN 8755-6316

- Kovacs, Judith L. "Now Shall the Ruler of This World Be Driven Out: Jesus’ Death as Cosmic Battle in John 12:20-36." Journal of Biblical Literature 114(2) (1995): 227-247.

- M'Cheyne, Robert M. Bethany - Discovering Christ's Love in Times of Suffering When Heaven Seems Silent, (a study of John 12) Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1846857027

- Metzger, Bruce M. The text of the New Testament: its transmission, corruption, and restoration. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0195072979

- Morris, L. The Gospel According to John.

- Robinson, John A. T. Redating the Gospels.

External links

All links retrieved June 27, 2017.

- Bible Gateway

- Online Bible at gospelhall.org

- The Egerton Gospel: text. Compare it with Gospel of John

- "Signs Gospel". a hypothetical written source for miracles in the Gospel of John: discussion

- John Rylands papyrus: text, translation, illustration and a bibliography of the discussion

- Conflicts Between the Gospel of John & the Remaining Three (Synoptic) Gospels on ReligiousTolerance.com.

|

|||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 21:45:13 | 16 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gospel_of_John | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF