African Dance

From Nwe

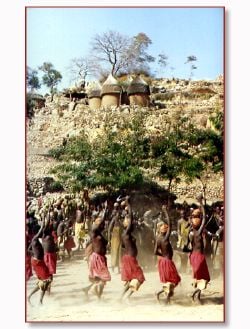

From Nwe African dance occupies central place in cultures throughout the African continent, embodying energy and a graceful beauty flowing with rhythm. In Africa, dance is a means of marking life experiences, encouraging abundant crops, honoring kings and queens, celebrating weddings, marking rites of passage, and other ceremonial occasions. Dance is also done purely for enjoyment. Ritual dance, including many dances utilizing masks, is a way of achieving communication with the gods. As modern economic and political forces have wrought changes on African society, African dance has also adapted, filling new needs that have arisen as many African people have migrated from villages toward the cities.

African dance is connected to Africa’s rich musical traditions expressed in African Music. African dance has a unity of aesthetic and logic that is evident even in the dances within the African Diaspora. To understand this logic, it is essential to look deeper into the elements that are common to the dances in the various cultures from East to West Africa and from North to South Africa.

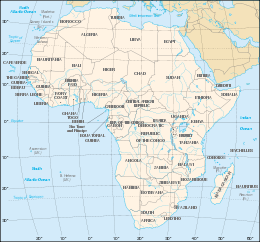

Africa covers about one-fifth of the world's land area and about an eighth of its people. Africa is divided into 53 independent countries and protectorates. The African people belong to several population groups and have many cultural backgrounds of rich and varied ancestry. There are over 800 ethnic groups in Africa, each with its own language, religion, and way of life.

Dance has always been an indispensable element of life in African society, binding together communities and helping individuals to understand their roles in relation to the community. In spiritual rituals, dance helps people to understand and remember their role in relation to the divine. Dance in social ceremonies and rights of passage has helped keep community life vibrant, contributing to a sense of security, safety and continuity. As the shape of communities has changed with the passage of time, with alterations in the political climate, and with the application of economic factors, some specifics in the role of dance have also adapted and changed, but today African dance still remains an important supporting element in the spiritual, emotional and social well-being of African society.

Traditional African dance

Traditional African dance is an essential element of Africa’s cultural heritage, providing a vital expression of the region's philosophy, and the living memory of its cultural wealth and its evolution over the centuries, as observed by Alphonse Tiérou:

Because it has more power than gesture, more eloquence than word, more richness than writing and because it expresses the most profound experiences of human beings, dance is a complete and self sufficient language. It is the expression of life and of its permanent emotions of joy, love, sadness, hope, and without emotion there is no African Dance.[1]

African dances are as varied and changing as the communities that create them. Although many types of African dance incorporate spirited, vigorous movement, there are also others that are more reserved or stylized. African dances vary widely by region and ethnic community. In addition, there are numerous dances within each given community. At the same time, there is a great deal of similarity in the role dance plays in each African community. African communities traditionally use dance for a variety of social purposes. Dances play a role in religious rituals; they mark rites of passage, including initiations to adulthood and weddings; they form a part of communal ceremonies, including harvest celebrations, funerals, and coronations; and they offer entertainment and recreation in the forms of masquerades, acrobatic dances, and social club dances. Most traditional African dance can be divided into three major categories: Ritual dances, ceremonial dances, and griotic dances (dances expressing local history).

Ritual dance

Ritual dance represents the broadest and most ancient of African dance. An example is the Mbira dance, the quintessential ritual dance of Zimbabwe. Ritual dance enforces and affirms the belief system of the society. As such, they are usually religious in nature and are designated for specific occasions that expedite and facilitate the most powerful expression of the African people that is ancestral reverence. Ritual dances are initiated by the informed and the elders. Throughout Africa, dance is also an integral part of the marking of birth and death. At burial ceremonies the Owo Yoruba perform the igogo, in which young men dance over the grave and pack the earth with stomping movements.

African religion

African ritual dance cannot be adequately discussed without an understanding of African religion and religious practice, because virtually every aspect of life in Africa is imbued with spirituality. Religion in Africa is not something reserved for a certain time or place, or a last resort to engage only in times of crisis.

To a great extent there is no formal distinction drawn between sacred and secular, religious and non-religious, spiritual or material. In many African languages there is no word for religion, because a person’s life is a total embodiment of his or her philosophy. By extension, sacred rituals are integral part of daily African life. They are interwoven with every aspect of human endeavor, from the profound to the mundane. From birth to death, every transition in an individual’s life is marked by some form of ritual observance. In a practical sense, these ubiquitous rituals are at the heart of religious practice in Africa.

Traditional African Religions are not exclusive. Individuals frequently participate in several distinctive forms of worship, and they are not perceived as conflicting in any way-rather they are considered cumulative means of achieving the same result, which is improved quality of life. When people grow old and die in most cultures of the world, it is a process of gradual detachment and finally leaving forever. The dead are believed to move on to a distant place where we no longer reach them; they cease to interact with the physical world and in time we forget them. In Africa, as people age, they are accorded more and more deference and respect. The deceased continue to play an active role in family and community life, and if anything become more respected and influential because of their deceased status. This extends to ancestral worship which is instrumental in traditional African religious practice.

Ancestral worship

Ancestor worship is common in Africa and is an important part of religious practice. The dead are believed to live on in the world of the spirit (Spirit World). In this form they posses supernatural powers of various sort. They watch over their living descendants with kindly interest, but have the ability to cause trouble if they are neglected or dishonored. Proper attention to the ancestors, especially at funerals and memorial services result in helpful intervention on behalf of the living. It also ensures that a pious individual will be favorably received when he or she inevitably joins the spirit world.

This kind of beliefs explains why the elderly are treated with much respect in African Societies. Among people who worship ancestors hundreds of years after their death, reverence for ages takes a mystical quality as though the living were slowly become gods. Each old man and woman is regarded as a priceless, irreplaceable treasure, the key to success in life. Because they have witnessed and participated in what has gone by, each one is appreciated as bearer of wisdom and experience in a society where custom and tradition are cherished. Guidance is often solicited from the elderly to solve questions of tradition or settle personal or family dispute.

Ritual dances to connect to the divine

Many African dances are the means by which individuals relate to ancestors and other divinities. What ever the motivation of the dance, it combines the expression of human feeling with the higher aspirations of man to communicate with the cosmos.

Dance is an integral part of a larger system. Dance expresses dynamic forces which constantly influence each other. Humans (both living and the dead), animals, vegetables, and minerals all posses this vital force in varying amounts. The supernatural entities which can benefit or hinder the endeavors of humankind are also composed of these same natural forces; to enlist their aid the human component is considered especially vital. In a sense, each divinity is created and empowered by the concentration and devotion of the worshipers, whose life force combines with that of, say an animal, or a river to bring the deity into power. If there is no human effort, there is no god and thus no chance to enhance the quality of life.

In African mythology there is a Supreme God, the Great and Almighty God, who is too far away to be of practical importance in daily life and so is not worshiped directly. There are numerous other spirits, deities and agents which act as intermediaries on behalf of humankind, and which are worshiped directly because they have direct influence over the affairs of man. Sometimes these agents are worshiped in the form of natural objects, such as stone, or rivers. Portrayals of this by non-Africans has shown their misconceptions about how Africans experience the world. To an African, everything in this world and beyond is explained in spiritual terms; consequently, nothing happens that is not interpreted as some form of divine intervention.

Gods and deceased ancestors must be treated with respect so that they will lend a helping hand when called to do so. It is important to learn about the proper use of natural forces and how to manifest the supernatural agents which can prevent sickness, improve harvest, ward off danger or untimely death, build happy marriage and families, bless children, and so forth. This ancient way of life motivates respectful attitudes towards traditional values and fellow human beings in a way that no legal or educational system can hope to match.

Ceremonial dance

Although ceremonial or cultural functions are more commemorative and transient than rituals, they are still important. Although the basic rhythms and movements remain, the number of dancers, formations and other elements change to fit the situation. Dances appear as parts of broader cultural activities. Dances of Love are performed on special accessions, such as weddings and anniversaries. One example is the Nmane dance performed in Ghana. It is done solely by women during weddings in honor of the bride. Rites of Passage and Coming of Age Dances are performed to mark the coming of age of young men and women. They give confidence to the dancers who have to perform in front of everyone. It is then formally acknowledged they are adults. This builds pride, as well as a stronger sense of community.

Dances of Welcome are a show of respect and pleasure to visitors, and at the same time provide a show of how talented and attractive the host villagers are. Yabara is a West African Dance of Welcome marked by The Beaded Net Covered Gourd Rattle (sekere-pronounced Shake-er-ay). It is thrown into the air to different heights by the female dancers to mark tempo and rhythm changes. This is an impressive spectacle, as all the dancers will throw and catch them at the same time.

Royal dances provide opportunities for chiefs and other dignitaries to create auras of majestic splendor and dignity to impress their office over the community at festivals and in the case of royal funerals, a deep sense of loss. In processions, the chief is preceded by various court officials, pages, guards, and others each with distinctive ceremonial dances or movements.

Dances of possession and summoning are common themes, and very important in many Traditional African Religions. They all share one common link: A call to a Spirit. These spirits can be the spirits of Plants or Forests, Ancestors, or Deities. The Orishas are the Deities found in many forms of African religion, such as Candomble, Santeria, Yoruba mythology, Voodoo, and others. Each orisha has their favorite colors, days, times, foods, drinks, music, and dances. The dances will be used on special occasions to honor the orisha, or to seek help and guidance. The orisha may be angry and need appeasing. Kakilambe is a great spirit of the forest who is summoned using dance. He comes in the form of a giant statue carried from the forest out to the waiting village. There is much dancing and singing. During this time the statue is raised up, growing to a height of around 15 inches. Then the priest communes and asks Kakilambe if they will have good luck over the coming years, and if there are any major events to be aware of, such as drought, war, or other things.

Griotic dance

In African culture, the Griot (GREEoh) or djialy (jali) is the village historian who teaches everyone about their past and keeper of cultural traditions and history of the people.

These traditions and stories are kept in the form of music and dance, containing elements of history or metaphorical statements that carry and pass on the culture of the people through the generations. Griotic dance not only represent historical documents, but they are ritual dramas and dances. The Dances often tell stories that are part of the oral history of a community. In Senegal, the Malinke people dance Lamba, the dance of the Griot (historian).

It is said that when a Griot dies, a library has burned to the ground. The music will usually follow a dance form, beginning slow with praise singing and lyrical movements accompanied by melodic instruments such as the kora, a 21-stringed harp/lute, and the balafon, a xylophone with gourd resonators.

Communal dances

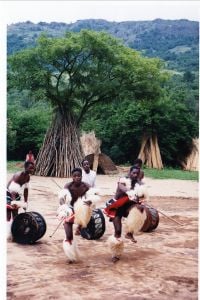

Traditionally, dance in Africa occurs collectively in a community setting. It expresses the life of the community more than the mood of an individual or a couple. In villages throughout the continent, the sound and the rhythm of the drum express the mood of the people. The drum is the sign of life; its beat is the heartbeat of the community. Such is the power of the drum to evoke emotions, to touch the souls of those who hear its rhythms. In an African community, coming together in response to the beating of the drum is an opportunity to give one another a sense of belonging and of solidarity. It is a time to connect with each other, to be part of that collective rhythm of the life in which young and old, rich and poor, men and women are all invited to contribute to the society.[2]

Dances mark key elements of communal life. For example, dances at agricultural festivals mark the passage of seasons, the successful completion of projects, and the hope for prosperity. In an annual festival of the Irigwe in Nigeria, men perform leaps symbolizing the growth of the crops.

Dance does not merely form a part of community life; it represents and reinforces the community itself. Its structures reproduce the organization and the values of the community. For example, dances are often segregated by sex, reinforcing gender identities to children from a young age. Dance often expresses the categories that structure the community, including not only gender but also kinship, age, status, and, especially in modern cities, ethnicity.

For example, in the igbin dance of the Yoruba of Nigeria the order of the performers in the dance reflects their social standing and age, from the king down to the youngest at the gathering. Among the Asante of Ghana the king reinforces his authority through a special royal dance, and traditionally he might be judged by his dancing skill. Dance can provide a forum for popular opinion and even satire within political structures. Spiritual leaders also use dance to symbolize their connection with the world beyond.

Dances provide community recognition for the major events in people's lives. The dances of initiation, or rites of passage, are pervasive throughout Africa and function as moments of definition in an individual's life or sometimes key opportunities to observe potential marriage partners. In Mali, Mandingo girls dance Lengin upon reaching their teenage years.

Highly energetic dances show off boys' stamina and are considered a means of judging physical health. The learning of the dance often plays an important part in the ritual of the occasion. For example, the girls among the Lunda of Zambia stay in seclusion practicing their steps before the coming-of-age ritual. Dance traditionally prepared people for the roles they played in the community. For example, some war dances prepared young men physically and psychologically for war by teaching them discipline and control while getting them into the spirit of battle. Some dances are a form of martial art themselves, such as Nigerian korokoro dances or the Angolan dances from which Brazilian capoeira is derived.

Essence of African dance

Formation

The basic formation of African dance is in lines and circles; dances are performed by lines or circles of dancers. There is supernatural power in the circle, the curved, and the round. “Let the circle be unbroken” is a popular creed throughout African. More complex shapes are formed through the combination of these basic forms, to create more sophisticated dance forms and style.

The African dancer often bends slightly toward the earth and flattens the feet against it in a wide, solid stance. Observers describe many of the dances as "earth centered," in contrast to the ethereal floating effects or soaring leaps found in European dance forms, such as ballet. In African dance, gravity provides an earthward orientation even in those forms in which dancers leap into the air, such as the dances of the Kikuyu of Kenya and the Tutsi of Rwanda.

Aesthetics

Western observers often focus on certain types of African dance that reinforced their stereotypes of Africans as sexualized and warlike peoples. Writers such as Joseph Conrad depicted African dance as an expression of both savagery and aggressiveness. However, European explorers of Africa understood little of either the aesthetics or the meanings of dances in the cultures they sought to scrutinize and conquer. A careful survey reveals the extraordinary variety in both the social meanings and aesthetic styles in African dance forms.

Unlike many Western forms of dance, in which the musicians providing the accompanying music and the audience both maintain a distance from the dance performance, in the traditional dance of many African societies, the dance incorporates a reciprocal, call-and-response or give-and-take relationship that creates an interaction between those dancing and those surrounding them. Many African dances are participatory, with spectators being part of the performance. With the exceptions of spiritual, religious, or initiation dances, there are traditionally no barriers between dancers and onlookers. Even among ritual dances there is often a time when spectators participate for a time.[3]

A rhythmic communication occurs amid the dancers and the drums in West Africa and between the dancers and the chorus in East Africa. The give-and-take dynamic found in African traditions all over the world reflects the rhythmic communication among dancers, music, and audience found in traditional African dance. The integration of performance and audience, as well as spatial environment, is one of the most noted aesthetic features of African dance. The one unifying aesthetic of African dance is an emphasis upon rhythm, which may be expressed by many different parts of the body or extended outside the body to rattles or costumes. African dances may combine movements of any parts of the body, from the eyes to the toes, and the focus on a certain part of the body might have a particular social significance. The Nigerian Urhobo women perform a dance during which they push their arms back and forth and contract the torso in synchronization with an accelerating rhythm beat by a drum. In Ivory Coast, a puberty dance creates a rhythmic percussion through the movement of a body covered in cowrie shells. Africans often judge the mastery of a dancer by the dancer's skill in representing rhythm. More skillful dancers might express several different rhythms at the same time, for example by maintaining a separate rhythmic movement with each of several different parts of the body. Rhythm frequently forms a dialogue between dancers, musicians, and audience.

Movement

One of the most characteristic aspects of African dance is its use of movements from daily life. By raising ordinary gestures to the level of art, these dances show the grace and rhythm of daily activities, from walking to pounding grain to chewing. The'Agbekor dance, an ancient dance once known as Atamga comes from the Foh and Ewe people of Togo and Ghana, and it is performed with horsetails. The movements of the dance mimic battlefield tactics, such as stabbing with the end of the horsetail. This dance consists of phrases of movements. A phrase consists of a “turn,” which occurs in every phrase, and then a different ending movement. These phrases are added back to back with slight variations within them.

In the Ivory Coast dance known as Ziglibit, stamping feet reproduce the rhythm of the pounding of corn into meal. During the Thie bou bien dance of Senegal, dancers move their right arms as if they were eating the food that gives the dance its name. The Nupe fishermen of Nigeria perform a dance choreographed to coincide with the motions of throwing fishing net.

African dance moves all parts of the body. Angular bending of arms, legs, and torso; shoulder and hip movement; scuffing, stamping, and hopping steps; asymmetrical use of the body; and fluid movement are all part of African dance.

Traditionalists describe the dancing body in Africa as a worshiping and worshiper body. It is a medium that embodies the experiences of life, pleasure, enjoyment, and sensuality. The body of the African dancer overflows with joy and vitality, it trembles, vibrates, radiates, it is charged with emotions. No matter what shape a dancer is—thick or thin, round or svelte, weak or muscled, large or small—as long as his emotions are not repressed and stifled, as long as the rational does not restrict his movements, but allows the irrational, which directs the true language of the body, to assert itself, the body becomes joyous, attractive, vigorous, and magnetic.

Movement and rhythm cannot be separated in African dance. Although there are many variations in the dance, depending on the theme, ethnic group or geography, there are elements which are common to all dances of Africa. African dances are characterized by musical and rhythmic sophistication. The movements of the dance initiate rhythms and then polyrhythm. The movements in African dance cannot be separated from the rhythms. Movement is essential to life, and rhythm makes movement more efficient. Movement which is fashioned and disciplined by rhythm of sound and body develops into dance movements.

Rhythm in movement and rhythm in sound combine to make work lighter as the Frafra grass cutting laborers show by stamping and grunting to the rhythm of their traditional fiddle and gourd shakers, bending down, cutting the grass and advancing as they raise their bodies in rhythm,as in a dance chorus. Girls from the Upper or Northern regions of Ghana or Nigeria pound millet in long mortars, creating counter-rhythms as the pestles pound and knock against the inside of the mortars.

Polyrhythm

African dance utilizes the concepts of polyrhythm, the simultaneous sounding of two or more independent rhythms, and total body articulation.[4] African Polyrhythmic dance compositions typically feature an ostinato (repeated) bell pattern known as a time line. African dance is not arranged into recurring phrases or refrains, but is the intensifying of one musical thought, one movement, one sequence, or the entire dance.

This intensification is not static; it goes by repetition from one level to another until ecstasy, euphoria, possession, saturation, and satisfaction have been reached. Time is a factor, but rather than a set amount of time, it is more than a feeling or realization that enough time has passed that determines when a dance is finished. Repetition is a common constant in African dance.

Since African music includes several rhythms at the same time, individual dancers will often express more than one beat at the same time. Dancers could move their shoulders to one beat, hips to another, and knees to a third. The rhythm of beats arranged one after another cannot compete with the complexity of polyrhythm in which the dancer may make several moves in one beat, simultaneously vibrating hands and head, double contracting the pelvis, and marking with the feet. This rhythmic complexity, with basic ground beat and counter beats played against it, formed the basis for later music such as samba, rumba capocira, ragtime, jazz, and rock and roll.

The polyrhythmic character of African dance is immediately recognizable and distinct. From the foot-stomping dance of Muchongoyo of eastern Zimbabwe to the stilt-walking Makishi of Zambia, to the Masked dance of Gelede in Nigeria, to the Royal Adowa and Kete of Ghana, to the knee sitting dance of Lesotho women, to the 6/8 rhythms of the samba from Brazil, to the rumba of Cuba, to the Ring Shout dance of Carolinas, to the snake dance of Angola, to the Ngoma Dance of Kenya, to the dust-flying dance of the Zulus of South Africa, to the High life of West Africa. The Khoi Khoi people of Botswana go even further with their language soundings of clicks only. The click sound has its counterpart in dance and is another demonstration of the polyrhythmic African sound. The rhythm of the click sound is not unique; it is the tradition of African Culture as seen in the Xhosa language. It is not just the memory of the Xhosa people singing, but the click itself that renders multiple sounds in one syllable that must be understood.

Pantomime

Many African dances reflect the emotions of life. Dance movement may imitate or represent animal behavior like the flight of the egret, enact human tasks like pounding rice, or express the power of spirits in whirling and strong forward steps.

Imitation and harmony as reflected and echoed in nature are symptomatic; not a materialistic imitation of the natural elements, but a sensual one. The imitation of the rhythm of the waves, the sound of the tree growing, the colors in the sky, the whisper and thunder of elephant's walk, the shape of the river, the movement of a spider, the quiver of breath, the cringing of concrete become source of inspiration.

Masquerades in dance take a number of different forms. Some masquerades are representative. For example, many of the pastoral groups of Sudan, Kenya, and Uganda perform dances portraying the cattle upon which their livelihood depends. During one such dance, the Karimojon imitate the movements of cattle, shaking their heads like bulls or cavorting like young cows. In stilt dances, another variety of masquerade, stilts extend the dancers' bodies by as much as 10 feet. In the gue gblin dance of the Ivory Coast, dancers perform an amazing acrobatic stilt dance traditionally understood as mediation between the ancestors and the living. At funerals and annual festivals, members of the Yoruba Egungun ancestral society perform in elaborate costumes representing anything from village chiefs to animals and spirits as they mediate between the ancestors and the living.

According to the beliefs of many communities, traditional African dancers not only represent a spirit, but embody that spirit during the dance. This is particularly true of the sacred dances involving masquerade. Dancers use a range of masks and costumes to represent spirits, gods, and sacred animals. These masks can be as much as 12 feet high; sometimes they cover the entire body and sometimes just the face. Acrobatic dances, such as those performed on stilts, are increasingly popular outside of their original sacred contexts. The Shope, the Shangana Tonga, and the Swazi of southern Africa perform complex dances in which dancers manipulate a long shield and spear with great finesse as they move through a series of athletic kicks. The Fulani acrobats of Senegal, the Gambia, and [Guinea]] perform movements similar to those of American break dancing, such as backspins head and handstands.

Modern African dance

Modern African dance is urban African dance. When African dances are taken out of their original, traditional village context, through migrations, often to multi-ethnic towns, and influenced by new [culture]], the cultural blending undermines the tight-knit communities so basic to traditional dance. Though, the traditional dances have survived in rural areas in connection with traditional ceremonies. Urban living has given rise to abundance of new dance forms.

Many things about traditional African dances change when they are brought to the stage from their original context in village life. For example, in African traditional dance, the dancers are not dancing in isolation, but are interacting directly with the rest of the people, who also participate in the ritual by singing, playing, and interacting with the musicians and dancers. When these dances are performed on a stage, they often incorporate new elements, illustrating how dance changes and develops when it encounters a new situation.

Colonialism and nationhood have contributed greatly to the transformation of African society, and new African dance forms have developed in new social contexts. As colonial rule shifted borders and the cash economy prompted labor migrations, and as people traveled during the colonial period, their dances went with them. As a consequence of labor migrations, people from a given ethnic group found themselves next to neighbors of a different ethnic group, with very different dance styles. As rural migrants gathered in cities, for example in South Africa, dance forms gained new significance as markers of ethnic origin and identity. Since the 1940s, at the Witwatersrand gold mines, "mine dancers" have competed in teams organized around ethnic origins.

After World War II, hybrid forms of dance emerged that integrated traditional African dances with European and American dance influences. High life was the most famous of these forms, synthesizing European ballroom dance techniques learned by soldiers abroad with traditional dance rhythms and forms. The high life music and dance rose to popularity in the cities of West Africa during the 1960s, cutting across ethnic boundaries to express a common regional identity derived from the experience of colonialism and urbanization. In southern African people danced in discos to the modern African beat of kwela, and in Central and East Africa, "Congo beat" music gained popularity.

The modern transformation of Africa has thus fostered remarkable creativity and diversity in dance forms. An essential element of everything from improvised traditional performance to ritual coming-of-age ceremonies to the nightlife of dance halls and discos, dance remains a vibrant and changing part of African life. The modernization of African dance has allowed both continuity and also innovation. Modern African dance can be categorized into dance clubs and Dance companies, this categorization does not include derivations, dance derived from the Africa dance.

Dance clubs

In the cities, traditional African dance is organized into formal institutions simply called dance clubs. It is because of these clubs that ancient and modern traditions both survive and adapt to serve new generations. The activities of the clubs enhance the lives of the their members and help to preserve their cultural roots.

In different African societies there are various types of dance clubs having many things in common. Most groups practices one specific style of African dance—the cultural, historical, or sacred dance forms from the members' home region. In these groups, membership is normally restricted to interested men and women from particular district and of a specific age group. The groups are usually governed by formal leadership with club rules; sometimes they even have a written constitution. The most important rules require member to attend rehearsal and performance, with failure punishable by a fine. Other rules might govern social behaviors among members and financial donations. Beyond these similarities, organization can vary widely. Some of these societies of dance clubs are a generation old while others have been formed recently—especially those organized in cities formed by immigrants from rural villages. Some groups meet weekly or monthly, others may come more often for funerals or special events. In addition to providing a way to preserve treasured dance traditions, the clubs also give members a safe haven amid the unfamiliarity of life in a new urban area.

As immigrants often live far from their extended families, the dance clubs provide a substitute community, extending support during difficult times, such as when a club member or one of his close relatives dies. Participates may also earn status and recognition as active members of the society. Dance clubs attract wealthy patrons of the arts for the same reason that Western Orchestra, operas, and dance companies do.

Dance companies

In recent years, modern artistic productions have increasingly drawn on traditional dances. Dance troupes performing on stage have integrated traditional forms with new, improvised themes and forms. Many of these dance companies are sponsored by national governments to promote their cultural heritage. The dance theater of the Ori Olokun Company of Ife, Nigeria, for example, created a performance called Alatangana that depicts a traditional myth of the Kono people in Guinea.

Other companies are private artistic companies, supported by philanthropists and others by individuals or groups. One dance of the Zulu in South Africa used rhythmic stomping and slapping of leather boots to express both the meter of work and a march against the oppression of apartheid. As a stirring cultural expression, dance is capable both of expressing tradition and forging a new national identity. With schools such as Mudra-Afrique, founded in 1977, in Dakar, and events such as the All-Nigeria Festival of Arts, national governments have used dance to transcend ethnic identity. Some dance companies, such as Les Ballets Africains in Guinea, the National Dance Company of Senegal, and the National Dance Company of Zimbabwe, gained international renown and represented their new nations abroad.

Gallery

-

Trance Dancers, Ouidah Benin

Notes

- ↑ Alphonse Tiérou, Dooplé: The Eternal Law of African Dance (Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1992, ISBN 9783718653065).

- ↑ Sebastian Bakare, The Drumbeat of Life: Jubilee in an African Context (Geneva, Switzerland: WCC Publications, 1997, ISBN 9782825412299).

- ↑ Kariamu Welsh-Asante, African Dance (Chelsea House Publishers, 2004, ISBN 9780791077764), 35.

- ↑ Welsh-Asante (2004), 28.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bakare, Sebastian. The Drumbeat of Life: Jubilee in an African Context. Risk book series, no. 80. Geneva: WCC Publications, 1997. ISBN 9782825412299.

- Dils, Ann, and Ann Cooper Albright. Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Middletown, CT: Wesleyn University Press, 2001. ISBN 9780819564139.

- Friedler, Sharon E., and Susan Glazer. Dancing Female: Lives and Issues of Women in Contemporary Dance. Choreography and dance studies, v. 12. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997. ISBN 9789057020261.

- Tiérou, Alphonse. 1992. Dooplé: The Eternal Law of African Dance. Choreography and dance studies, v. 2. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1992. ISBN 9783718653065.

- Welsh-Asante, Kariamu. African Dance. World of dance. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2004. ISBN 9780791077764.

- Welsh-Asante, Kariamu. African Dance: An Artistic, Historical, and Philosophical Inquiry. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1996. ISBN 9780865431973.

- Welsh-Asante, Kariamu. Zimbabwe Dance: Rhythmic Forces, Ancestral Voices: An Aesthetic Analysis. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2000. ISBN 9780865434936.

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2021.

- Alokli West African Dance Club, Marin County.

- African Dance in the Diaspora.

- Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre

- Forces of Nature Dance Theatre Company

- Kankouran West African Dance Company

- Savoy Style: African Influences on Swing Dance

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:40:55 | 47 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/African_dance | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF