Spinal And Bulbar Muscular Atrophy

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki | Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: spinobulbar muscular atrophy, bulbo-spinal atrophy, X-linked bulbospinal neuropathy (XBSN), X-linked spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMAX1), Kennedy's disease (KD), and many other names[1] | |

| |

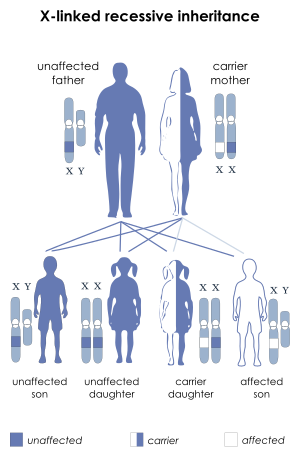

| SBMA is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern. | |

| Symptoms | Muscles cramps[2] |

| Causes | Mutation in the AR gene[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical features, Family history[4] |

| Treatment | Physical therapy [4] |

Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), popularly known as Kennedy's disease, is a progressive debilitating neurodegenerative disorder resulting in muscle cramps and progressive weakness due to degeneration of motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord.[5][6]

The condition is associated with mutation of the androgen receptor (AR) gene[7][8] and is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner. As with many genetic disorders, no cure is known, although research continues. Because of its endocrine manifestations related to the impairment of the AR gene, SBMA can be viewed as a variation of the disorders of the androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS). It is also related to other neurodegenerative diseases caused by similar mutations, such as Huntington's disease.[9] SBMA prevalence has been estimated at 2.6:100,000 males.[10]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

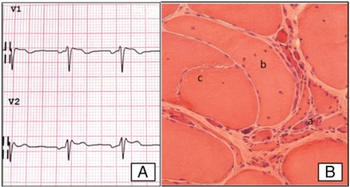

Individuals with SBMA have muscle cramps and progressive weakness due to degeneration of motor neurons in the brain stem and spinal cord. Ages of onset and severity of manifestations in affected males vary from adolescence to old age, but most commonly develop in middle adult life. The syndrome has neuromuscular and endocrine manifestations.[6]

Neuromuscular[edit | edit source]

Early signs often include weakness of tongue and mouth muscles, fasciculations, and gradually increasing weakness of limb muscles with muscle wasting. Neuromuscular management is supportive, and the disease progresses very slowly, but can eventually lead to extreme disability.[11] Further signs and symptoms include:

- Bulbar signs: bulbar muscles are those supplied by the motor nerves from the brain stem, which control swallowing, speech, and other functions of the throat.[4]

- Lower motor neuron signs: lower motor neurons are those in the brainstem and spinal cord that directly supply the muscles, loss of lower motor neurons leads to weakness and wasting of the muscle.[4]

- Respiratory musculature weakness[4]

- Action tremor[4]

- Babinski response: when the bottom of the foot is scraped, the toes bend down (an abnormal response would be an upward movement of the toes indicating a problem with higher-level (upper) motor neurons).[12]

- Decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes [4]

Muscular

- Cramps: muscle spasms[4]

- Muscular atrophy: loss of muscle bulk that occurs when the lower motor neurons do not stimulate the muscle adequately[4]

Endocrine

- Gynecomastia: male breast enlargement[13]

- Erectile dysfunction[13]

- Reduced fertility[13]

- Testicular atrophy: testicles become smaller and less functional[14]

Other

- Late onset: individuals usually develop symptoms in their late 30s or afterwards (rarely is it seen in adolescence) [4]

Homozygous females[edit | edit source]

Homozygous females, both of whose X chromosomes have a mutation leading to CAG expansion of the AR gene, have been reported to show only mild symptoms of muscle cramps and twitching. No endocrinopathy has been described.[14]

Genetics[edit | edit source]

SBMA is a hereditary syndrome, inherited in an X-linked recessive manner.[7] The AR gene, located in the X chromosome, involves a section consisting of CAG repeats. The number of repeats varies among individuals. Healthy males carry up to 34 repeats. From 35 to around 46 repeats, penetrance (the possibility that the individual manifests the disease) gradually increases, approaching a maximum value (full penetrance).[10] Therefore, males bearing 35 to 46 CAG repeats are at intermediate but increasing risk for developing SBMA. Males bearing 47 or more repeats have nearly 100% risk of developing SBMA.[10] Other, still unidentified genetic factors may also play a role in disease manifestation and symptoms’ severity. Genetic founder effects are likely to be responsible for the higher prevalence of SBMA observed in certain geographic regions.[citation needed]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

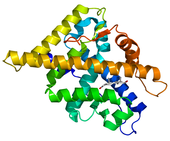

The mechanism behind SBMA is caused by expansion of a CAG repeat in the first exon of the androgen receptor gene (trinucleotide repeats). The CAG repeat encodes a polyglutamine tract in the androgen receptor protein. The greater the expansion of the CAG repeat, the earlier the disease onset and more severe the disease manifestations. The repeat expansion likely causes a toxic gain of function in the receptor protein, since loss of receptor function in androgen insensitivity syndrome does not cause motor neuron degeneration.[15]

Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy may share mechanistic features with other disorders caused by polyglutamine expansion, such as Huntington's disease. No cure for SBMA is known.[16]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of SBMA is based on identifying the number of CAG repeats in the AR gene using molecular techniques such as PCR. The accuracy of such techniques is nearly 100%.[7] Additionally one should also look for the following:[17]

- Gynecomastia

- Muscle weakness-limbs

- Dysarthria

- No upper motor neuron disease signs

- Family history

Management[edit | edit source]

In terms of the management of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, no cure is known and treatment is supportive. Rehabilitation to slow muscle weakness can prove positive, though the prognosis indicates some individuals will require the use of a wheelchair in later stages of life.[18]

Surgery may achieve correction of the spine, and early surgical intervention should be done in cases where prolonged survival is expected. Preferred nonsurgical treatment occurs due to the high rate of repeated dislocation of the hip.[13]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

A 2006 study followed 223 patients for a number of years. Of these, 15 died, with a median age of 65 years. The authors tentatively concluded that this is in line with a previously reported estimate of a shortened life expectancy of 10–15 years (12 in their data).[19]

History[edit | edit source]

This disorder was first described by William R. Kennedy in 1968.[5] In 1991, it was recognized that the AR gene is involved in the disease process.[7]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Arvin, Shelley (2013-04-01). "Analysis of inconsistencies in terminology of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy and its effect on retrieval of research". Journal of the Medical Library Association. 101 (2): 147–150. doi:10.3163/1536-5050.101.2.010. ISSN 1536-5050. PMC 3634378. PMID 23646030.

- ↑ "Kennedy disease | Disease | Overview | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ↑ "Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy". Genetics Home Reference. 2016-03-21. Archived from the original on 2016-04-03. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 La Spada, Albert (1993-01-01). Pagon, Roberta A.; Adam, Margaret P.; Ardinger, Holly H.; Wallace, Stephanie E.; Amemiya, Anne; Bean, Lora J.H.; Bird, Thomas D.; Fong, Chin-To; Mefford, Heather C. (eds.). Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301508. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2021-08-18. Update: July 3, 2014

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kennedy, W. R.; Alter, M.; Sung, J. H. (1968). "Progressive proximal spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy of late onset. A sex-linked recessive trait". Neurology. 18 (7): 671–680. doi:10.1212/WNL.18.7.671. PMID 4233749. S2CID 45735233.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 A, La Spada (1993–2020). "Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy". PMID 20301508.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Krivickas, L. S. (2003). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other motor neuron diseases". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 14 (2): 327–345. doi:10.1016/S1047-9651(02)00119-5. PMID 12795519.

- ↑ Chen CJ, Fischbeck KH (2006). "Ch. 13: Clinical aspects and the genetic and molecular biology of Kennedy's disease". In Tetsuo Ashizawa, Wells, Robert V. (eds.). Genetic Instabilities and Neurological Diseases (2nd ed.). Boston: Academic Press. pp. 211–222. ISBN 978-0-12-369462-1.

- ↑ Browne SE, Beal MF (Mar 2004). "The energetics of Huntington's disease". Neurochem Res (Review). 29 (3): 531–46. doi:10.1023/b:nere.0000014824.04728.dd. PMID 15038601. S2CID 20202258.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Laskaratos, Achilleas; Breza, Marianthi; Karadima, Georgia; Koutsis, Georgios (2020-06-22). "Wide range of reduced penetrance alleles in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: a model-based approach". Journal of Medical Genetics: jmedgenet–2020–106963. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-106963. ISSN 0022-2593. PMID 32571900.

- ↑ Grunseich, Christopher; Fischbeck, Kenneth H. (2015-11-01). "Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy". Neurologic Clinics. 33 (4): 847–854. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.002. ISSN 1557-9875. PMC 4628725. PMID 26515625.

- ↑ Sikka, Paul K.; Beaman, Shawn T.; Street, James A. (2015-04-09). Basic Clinical Anesthesia. Springer. p. 470. ISBN 9781493917372.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "Clinical Features of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy". Archived from the original on 2020-08-05. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "OMIM Entry - # 313200 - SPINAL AND BULBAR MUSCULAR ATROPHY, X-LINKED 1; SMAX1". omim.org. Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ↑ Adachi, H.; Waza, M.; Katsuno, M.; Tanaka, F.; Doyu, M.; Sobue, G. (2007-04-01). "Pathogenesis and molecular targeted therapy of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 33 (2): 135–151. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00830.x. ISSN 1365-2990. PMID 17359355. S2CID 73301743.

- ↑ Merry, D. E. (2005). "Animal Models of Kennedy Disease". NeuroRx. 2 (3): 471–479. doi:10.1602/neurorx.2.3.471. PMC 1144490. PMID 16389310.

- ↑ La Spada, Albert (1993). "Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy". GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ↑ "Kennedy's Disease Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". NIH. Archived from the original on 2017-01-04. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ↑ Atsuta, Naoki (2006). "Natural history of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA): a study of 223 Japanese patients". Brain. 129 (6): 1446–1455. doi:10.1093/brain/awl096. PMID 16621916.

Further reading[edit | edit source]

- Manzano, Raquel; Sorarú, Gianni; Grunseich, Christopher; Fratta, Pietro; Zuccaro, Emanuela; Pennuto, Maria; Rinaldi, Carlo (2018). "Beyond motor neurons: expanding the clinical spectrum in Kennedy's disease". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 89 (8): 808–812. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-316961. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 6204939. PMID 29353237.

- "Study of Hepatic Function in Patients With Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-04-03. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- Chedrese, P. Jorge (2009-06-13). Reproductive Endocrinology: A Molecular Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780387881867. Archived from the original on 2020-09-13. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- Rhodes, Lindsay E.; Freeman, Brandi K.; Auh, Sungyoung; Kokkinis, Angela D.; Pean, Alison La; Chen, Cheunju; Lehky, Tanya J.; Shrader, Joseph A.; Levy, Ellen W. (2009-12-01). "Clinical features of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy". Brain. 132 (12): 3242–3251. doi:10.1093/brain/awp258. ISSN 0006-8950. PMC 2792370. PMID 19846582.

External links[edit | edit source]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Categories: [Transcription factor deficiencies] [Endocrine gonad disorders] [Motor neuron diseases] [Neuromuscular disorders] [X-linked recessive disorders] [Rare diseases]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 12/26/2023 18:00:04 | 1 views

☰ Source: https://mdwiki.org/wiki/Spinal_and_bulbar_muscular_atrophy | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF