Confederated Salish And Kootenai Tribes Of The Flathead Nation

From Nwe

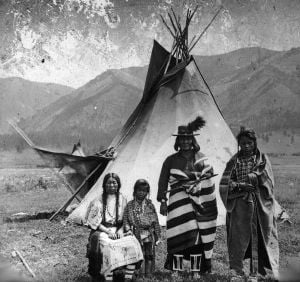

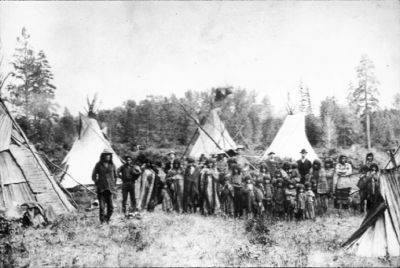

From Nwe The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation are the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles (Kalispel) Native American tribes. They followed the lifestyle of the Plateau Indians, traveling to hunt buffalo and living in tipis like the Plains Indians, but also having access to reliable food sources in the form of fish, particularly salmon, in the many rivers and streams of their homelands; they also gathered berries and roots, particularly camas.

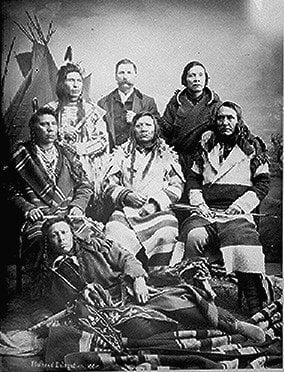

These tribes were peaceful, except for historical enmity with the Blackfeet, and welcomed white explorers and traders. They learned of the Catholic religion through the Iroquois and requested missionaries to come and minister to them. When missions were established they converted to Christianity. They signed the Treaty of Hellgate in 1855. There was misunderstanding on the part of the tribal leaders, as the treaty ceded most of their homelands to the United States government, leaving them a smaller portion, the Flathead Reservation, to which most tribal members were eventually relocated, some forcibly. Hard working and adaptable, the majority of these people were able to adjust to the reservation lifestyle and today have some successful business and educational ventures. They have made efforts to maintain and revitalize their cultural heritage in ways that are compatible with contemporary society.

History

Pre-contact

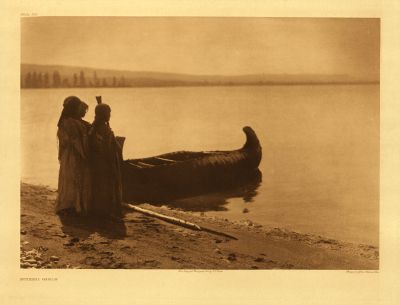

The Pend d'Oreilles, also known as the Kalispel, lived around Lake Pend Oreille, the Pend Oreille River, and Priest Lake in the northern Idaho Panhandle. They lived separately from the Bitterroot Salish and the Kootenai until after the signing of the Treaty of Hellgate in 1855.

The Bitterroot Salish and Kootenai tribes originally lived in the areas of Montana, parts of Idaho, British Columbia, and Wyoming. During the 1700s, these two tribes shared common hunting and gathering grounds.

The Bitterroot Salish (Flatheads) initially lived entirely east of the Continental Divide but established their headquarters near the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. Occasionally, hunting parties went west of the Continental Divide but never east of the Bitterroot Range. The easternmost edge of their ancestral hunting forays were the Gallatin, Crazy Mountain, and Little Belt Ranges. Their language is part of the Salishan languages group.

Unlike most other tribes in Montana, the Bitterroot Salish migrated from the west. The Salish occupied territory in Washington, Idaho, and western Montana but ventured as far east as the Bighorn Mountains. After acquiring horses in the early 1700s, they moved east, changing from a lifestyle based on salmon fishing to one more dependent on native plants and buffalo (Waldman 2006).

The Kootenai, however, are native to Montana. Archaeological evidence shows that Native Americans inhabited Montana more than 14,000 years ago, and artifacts indicate that the Kootenai have roots in the area's prehistory. The Kootenai inhabited the mountainous terrain west of the Continental Divide, venturing only seasonally to the east for buffalo hunts. The Kootenai were divided into two main groups. One band lived to the northeast and had a lifestyle based on buffalo hunting. The other band lived in the mountainous west and their lifestyle centered around rivers and lakes.

Post-contact

The first written record of these tribes is from their meeting with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, where the "Flatheads" are described in detail and the Kalispel are mentioned under the name "Coospellar" (Lewis and Clark 2002). The "Flatheads" also appear in the records of the Catholic Church at St. Louis, Missouri to which they sent four delegations to request missionaries (or "Black Robes") to minister to the tribe (Shea 1855). The Kootenai had also encountered traders through the Hudson's Bay Company. David Thompson, the explorer, had crossed the Rocky Mountains and established trading posts in Northwestern Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Western Canada; including Kootenae House and later Saleesh House, the first trading post west of the Rockies in Montana, thereby successfully extending North West Company fur trading territories.

Treaty of Hellgate

The Treaty of Hellgate was signed on July 16, 1855, between Indian commissioner Isaac Stevens and the tribes located in western Montana. The treaty was ratified by Congress, signed by President James Buchanan, and proclaimed on April 18, 1859 (Prucha 1994).

The tribes involved in the signing of the treaty were the Bitterroot Salish, Pend d'Oreilles, and the Kootenai. Based on the terms of the accord, the Native Americans were to relinquish their territories to the United States government in exchange for payment installments that totaled 120,000 dollars. The original territory comprised about 22 million acres (89,000 km²) at the time of the treaty. The territories ceded were from the main ridge of the Rocky Mountains at the 49th parallel to the Kootenay River and Clark Fork to the divide between the St. Regis Borgia River and the Coeur d'Alene River. From there, the ceded territories also extend to the southwestern fork of the Bitter Root River and up to Salmon River and Snake River. This area totaled approximately 20 million acres; the remainder of their homeland became the Flathead Reservation.

From the start, the negotiations were plagued by serious translation problems. Father Adrian Hoecken, said that the translations were so poor that "not a tenth of what was said was understood by either side." However, as in the meeting with Lewis and Clark, the pervasive miscommunication ran even deeper than problems of language and translation. Tribal people came to the meeting assuming they were going to formalize an already-recognized friendship. Non-Indians came with the goal of making official their claims to native lands and resources. Isaac Stevens, the new governor and superintendent of Indian affairs for Washington Territory, was intent on obtaining cession of the Bitterroot Valley from the Salish. Many non-Indians were already well aware of the valley's potential value for agriculture and its relatively temperate climate in winter. Due to the resistance of Chief Victor (Many Horses), Stevens ended up inserting into the treaty complicated (and doubtless poorly translated) language that defined the Bitterroot Valley south of Lolo Creek as a "conditional reservation" for the Salish. Chief Victor put his X mark on the document, convinced that the agreement would not require his people to leave their homeland. No other word came from the government for the next fifteen years, so the Salish assumed that they would indeed stay in their Bitterroot Valley forever.

Over time, the real reason for the Hellgate treaty meetings became clear to the Salish and Pend d'Oreilles people. Under the terms spelled out in the written document, the tribes ceded to the United States more than twenty million acres (81,000 km²) of land and reserved from cession about 1.3 million acres (5300 km²), thus forming the Jocko or Flathead Indian Reservation. After the 1864 gold rush in newly established Montana Territory, pressure upon the Salish intensified from both illegal non-Indian squatters and government officials. In 1870, Chief Victor died, and he was succeeded as chief by his son, Chief Charlot (Claw of the Little Grizzly). Like his father, Chief Charlot adhered to a policy of nonviolent resistance. He insisted on the right of his people to remain in the Bitterroot Valley. However, territorial citizens and officials thought the new chief could be pressured into capitulating. In 1871, they successfully lobbied President Ulysses S. Grant to declare that the survey required by the treaty had been conducted and that it had found that the Jocko (Flathead) Reservation was better suited to the needs of the natives. On the basis of Grant's executive order, Congress sent a delegation, led by future president James Garfield, to make arrangements with the tribe for their removal.

Conditions had become intolerable by the late 1880s, after the Missoula and Bitter Root Valley Railroad was constructed directly through their lands, with neither permission from the native owners nor payment to them. Chief Charlot refused to sign the agreement to leave the Bitterroot Valley, and U.S. officials then simply forged Charlot's "X" onto the official copy of the agreement that was sent to the Senate for ratification. Inaction by Congress, however, delayed the removal for another two years, and according to some observers, the tribe's desperation reached a level of outright starvation. In October 1891, Chief Charlot and the remaining tribal members left the Bitterroot and marched sixty miles to the Flathead Reservation.

Bitterroot Salish

Called the Flathead Indians by the first white men who came to the Columbia River, the Bitterroot Salish call themselves Salish ("the people"). The term "Flathead" derives from the flat skull produced by binding infant's skulls with boards. However, this tribe never practiced head flattening, but rather were called "Flat head" because the tops of their heads were not pointed like those of neighboring tribes people who did practice vertical head-binding. The sign language used by neighboring tribes to distinguish the "Flatheads" consisted of "pressing each side of the head" with the hands.

Their lifestyle was typical of the Plateau Indians, gathering wild roots, particularly camas, and living in mat-covered lodges, and also hunting buffalo and living in tipis part of the year. They were reported to be peaceful, except for historical enmity with the Blackfeet (Mooney 1909).

Originally the Salish practiced an animistic religion with ceremonial dances, notably the Sun Dance. However, when they met the Iroquois through trade with the Hudson's Bay Company they learned of the Catholic religion. In 1831, they sent a delegation to St. Louis requesting missionaries be sent to them. In 1840, Jesuit Father Pierre-Jean De Smet responded to this request. Welcomed by a gathering of some 1600 members, he established the mission of St. Mary on the Bitter Root river. Although this was later abandoned due to incursions by the Blackfeet, conversion to Catholicism was successful and a new mission of St. Ignatius was established in 1845, by Fathers De Smet and Adrian Hoecken; in 1854, that mission was moved to its present location in St. Ignatius, Montana, and has continued in operation to contemporary times (Thompson).

In 1855, they signed the Treaty of Hellgate ceding the majority of their homeland to the Americans. Although there was misunderstanding, and the Salish expected to be able to continue to live in the Bitterroot area, they were eventually relocated to the portion of their lands that had become the Flathead Reservation in Montana.

By the early twentieth century it was reported that the Salish were increasing in population on the Flathead Reservation. They were considered "moral, devoted Catholics, and in every way a testimony to the zeal and ability of their religious teachers," and had adjusted their lifestyle to become "prosperous and industrious farmers and stockmen" (Mooney 1909).

Pend d'Oreilles

The Pend d'Oreilles, also known as the Kalispel, lived around Lake Pend Oreille, as well as the Pend Oreille River, and Priest Lake although some of them live spread throughout Montana and eastern Washington. The primary tribal range from roughly Plains, Montana westward along the Clark Fork River, Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho, and the Pend Oreille River in Eastern Washington and into British Columbia was given the name Kaniksu by the Kalispel peoples. The name Pend d'Oreilles is of French origin, meaning "hangs from ears," which refers to the large shell earrings that these people wore. Their language, Kalispel-Pend d'Oreille, belongs to the Salishan languages family.

The Pend d'Oreilles were generally peaceable. They made tools from flint, and many other things were shaped with rocks. For housing, the Pend d'Oreilles lived in tipis in the summer, as well as lodges in the winter time. These houses were all built out of large cattails, which were available in abundance. These cattails were woven into mats called "tule mats" which were attached to a tree branch frame to form a hut.

The traveled to gather their food on a seasonal basis, while also maintaining more permanent areas that they farmed. Camas was a staple, baked and dried to preserve it not only through the winter but for several years. They caught salmon, which they dried and thus preserved a year's supply. Berries were also gathered and dried. In the winter they hunted and trapped, trading furs for supplies.

The horses they needed came from trading buffalo skins. They people wore robes as well as skins for clothing. They decorated themselves with dyes, paints, beads, and sometimes even animal quills.

In 1844, the Jesuit Father Adrian Hoecken began missionary work with the Pend d'Oreilles, establishing the St. Ignatius Mission with Father Pierre-Jean De Smet. Through this missionary work the Pend d'Oreilles were successfully converted to Christianity, as were the other tribes in the area.

In 1855, the "Upper band" who lived around the lake joined with the Salish and Kootenai in signing the Treaty of Hellgate, and were settled on the Flathead Reservation in Montana. Some of the "Lower band" who lived on the river joined them; others of this group settled on a reservation in Washington state.

Kootenai

The Kootenai (also spelled Kutenai) or Ktunaxa (pronounced in English as /k.tuˈnæ.hæ/) are one of three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana, and they form the Ktunaxa Nation in British Columbia. There are also populations in Idaho and Washington in the United States.

The tribes constitute a distinct stock (Kitunahan). They were known by the neighboring Salish as Skalzi (lake or water people), and to the French as Arez-à-plats (Flatbows). There is evidence that they formerly lived in the eastern plains, east of the Rockies, but were driven into the mountains by the Blackfeet (Mooney 1910b).

The Kootenai had a similar subsistence lifestyle to the Salish and Pend d'Oreilles—hunting, fishing, and gathering wild berries and camas roots, and living in tipis and lodges. They dressed in buckskin, painted their faces, and wore their hair long. Their social organization was simple, with each band having a chief and council. They had none of the secret societies that were found in other tribes (Mooney 1910b).

Prior to converting to Catholicism when Father De Smet established the mission among the Salish, they practiced shamanism and held animistic beliefs, particularly worshiping:

the sun, personified as a woman, as the highest and most beneficent deity, to whose home the spirits of the dead journeyed, to rejoin their friends later in this world at a place of sacred pilgrimage, on the shore of Lake Pend d'Oreille (Mooney 1910b).

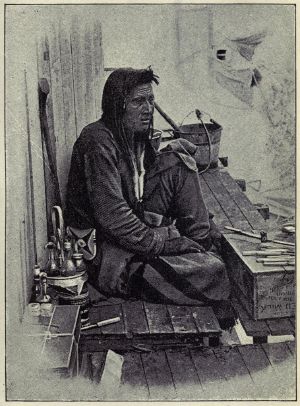

The Kootenai were friendly toward whites, and David Thompson, the Canadian explorer who established trading relations for the North West Company with many tribes, established a trading post called Kootenai House in 1807. In his visits to the area, Thompson encountered Kaúxuma Núpika, a Kootenai woman. According to the entries Thompson made in his journal concerning her, she spent time as a sort of second wife to a man named Boisverd, who was one of Thompson's men. Thompson eventually sent her away.

Kaúxuma then claimed to have been transformed by the whites into a man and now had spiritual powers. From this time Kaúxuma took several wives, served as a guide to traders, as well as fighting as a warrior with the Kootenai men and taking the role of shaman and prophet (Waldman 2008). Kaúxuma is thus an example of a female-bodied two-spirit person, a transgender type not uncommon among Native American tribes, many of whom foretold the future. When Thomson encountered Kaúxuma again in 1809, he wrote:

She had set herself up for a prophetess and gradually had gained, by her shrewdness, some influence among the natives as a dreamer, and expounder of dreams. She recollected me before I did her, and gave a haughty look of defiance, as much to say, I am now out of your power (Tyrrell 2008).

In 1811, Kaúxuma walked into Thomson's camp seeking asylum. Thompson described this "Manlike Woman" as "apparently a young man, well dressed in leather, carrying a Bow and Quiver of Arrows, with his Wife, a young woman in good clothing" (Tyrrell 2008). Kaúxuma continued to act as a shaman and prophet, predicting large numbers of white people coming to the area and bringing diseases. In 1837, while acting as a mediator between the Blackfeet and the Salish, Kaúxuma was killed by the Blackfeet.

The majority of Kootenai within the United States moved to the Flathead Reservation in Montana following the Treaty of Hellgate in 1855. The Oblate Fathers established a mission in British Columbia and Kootenai in that region were educated there.

By the beginning of the twentieth century the Kootenai were considered "civilized" and dedicated Christians, who carried out farming, stock-raising, and working in the lumber camps. Despite epidemics of European introduced diseases, notable smallpox, which reduced their number, they had a stable population. They were described as "industrious, steady, and law-abiding," "temperate and moral" (Mooney 1910b).

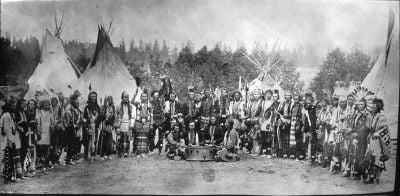

Contemporary life

Contemporary Salish, Kootenai, and Kalispels live on reservations that form a small part of their ancestral territory. Although their population is small, they have maintained their identity and have made great efforts to adapt to the contemporary situation while never forgetting their heritage, history, and culture. Visitors are invited to learn this history at their museums, which contain tribal artifacts and exhibits, and to attend pow-wows, held annually on the reservations, in order to learn more of their culture.

Flathead Indian Reservation

The Flathead Indian Reservation of around 1.3 million acres (5,300 km²), located in western Montana on the Flathead River, is home to the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles Tribes, together known as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation. The Reservation was created through 1855 Treaty of Hellgate and includes parts of four Montana counties: Lake, Sanders, Missoula, and Flathead. The Flathead Indian Reservation is an area of of forested mountains and valleys just west of the Continental Divide.

The largest community on the reservation is the city of Polson, which is also the county seat of Lake County.

As the first to organize a tribal government under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1936, the tribes are governed by a tribal council of ten members. The tribal government offers a number of services to tribal members and is the chief employer on the reservation. The tribes operate a tribal college, the Salish Kootenai College, and a heritage museum called "The People's Center" in Pablo, the seat of the tribal government.

Salish Kootenai College (SKC) is a Native American tribal college based in Pablo, Montana which serves the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles tribes. There are approximately 1,100 students attending the college; enrollment is not limited to Native American students. Prior to 1978, it was a branch campus of Flathead Valley Community College (FVCC). In 1981, the college formally disassociated itself from FVCC and became completely self-governing. It is member of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

Flathead Lake is the largest lake in the western part of the coterminous United States, surpassing Nevada/California's Lake Tahoe by .5 miles (0.80 km) in surface area, 5 miles (8.0 km) in length, and about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) in width, Flathead Lake is also the largest lake in the state of Montana. This lake is one of the cleanest in the world for its size and type. Once known as "Salish Lake," this body of water takes its name from the tribes who live at the southern end of the lake on the Flathead Indian Reservation. Kerr Dam, near Polson, regulates the lake's water level and provides hydroelectric power and water for irrigation. Flathead Lake is 30 miles (48 km) southwest of Glacier National Park and is flanked by two scenic highways, which wind along its curving shoreline. The lake is a popular tourist attraction, offering fishing and other water activities as well as scenic views and hiking in the mountains which border its shores. The KwaTaqNuk resort on Flathead Lake brings in revenue from tourism. The tribes also receive revenue from the valuable hydropower dam, Kerr Dam.

Kalispel Indian Reservation

The Kalispel Indian Reservation is northwest of Newport, Washington, in central Pend Oreille County. The total land area of the Kalispel Indian Reservation is 18.840 km² (7.274 sq mi). The main reservation is an 18.638 km² (7.196 sq mi) strip of land along the Pend Oreille River, west of the Washington-Idaho border. There is also a small parcel of land in the western part of the Spokane metropolitan area in the city of Airway Heights, with a land area of 0.202 km² (49.92 acres), the site of Northern Quest Casino which is operated by the tribe. The Northern Quest Casino provides nearly 1,000 jobs for members of the local community.

Kootenai Indian Reservation

The Kootenai Indian Reservation lies in central Boundary County, Idaho, about 40 kilometers (25 mi) south of the Canadian border, and about 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) west-northwest of the city of Bonners Ferry. It has a land area of only 0.076575 km² (18.922 acres).

On September 21, 1975, the Kootenai Tribe headed by Chairwoman Amy Trice declared war on the United States government. Their first act was to post soldiers on each end of the highway that runs through the town and they forced people, at gunpoint, to pay a toll to drive through the area that had been the tribe’s aboriginal land. The money was to be used to house and care for elderly tribal members. The tribe also issued "Kootenai Nation War Bonds" that sold at $1.00 each. Most tribes in the United States are forbidden to declare war on the U.S. government because of treaties, but the Kootenai Tribe never signed a treaty. The dispute resulted in concession by the United States government and a land grant of 12.5 acres that became the Kootenai Reservation.

Since that time, the Kootenai have worked to preserve their traditions, language, and culture while at the same time establishing economic independence. An important step in their economic growth was the opening of the Kootenai River Inn in 1986. A decade later this inn became the site of the Kootenai Casino and was fully renovated to become a luxury resort and spa. The success of this Best Western Plus Kootenai River Inn Casino & Spa has enabled Kootenai youth to pursue higher education and career goals.

Kootenay Reserves in British Columbia

Four bands of Kootenay (preferred spelling in Canada) live on various reserves in the southeastern corner of British Columbia, from the U.S. border north to the Invermere area, and as far west as Creston: The Lower Kootenay Band (Yaqan nu?kiy) have eight reserves established in 1906 on 2,553 hectares of land on the Kootenay River. The St. Mary's Band (?Aq'am) live on five reserves established in 1884 on 7,850 hectares of land; their main community is on the west bank of the Kootenay River at the mouth of the St. Mary's River. The Tobacco Plains Band has two reserves on 4,418 hectares of land adjacent to the U.S. border, established in 1884. The Columbia Lake Band (Akisq'nuk) has two reserves on 3,412 hectares of land at Windermere Lake, established in 1884.

These bands are affiliated with the Ktunaxa Nation Council, formerly known as the Ktunaxa/Kinbasket Tribal Council. At the beginning of the twenty-first century there were approximately 1,000 registered members of the Ktunaxa Nation in British Columbia.

The Kootenay are active in business initiatives such as golf courses, campgrounds, a guide outfitting territory, and housing developments, in addition to more traditional activities such as trapping, hay and livestock ranching, and arts and crafts. In October, 2010 the Province of British Columbia and the Ktunaxa Nation Council signed the Ktunaxa Strategic Engagement Agreement (SEA) providing for government-to-government discussions on natural resource decisions within Ktunaxa territory.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beaverhead, Pete, and Dwight Billedeaux. 2000. Mary Quequesah's Love Story: A Pend D'Oreille Indian Tale. Pablo, MT: Salish Kootenai College Press. ISBN 0917298713.

- Bigart, Robert, and Clarence Woodcock. 1996. In the Name of the Salish & Kootenai Nation: The 1855 Hell Gate Treaty and the Origin of the Flathead Indian Reservation. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295975458.

- Boas, Franz et al. 1917. Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin Tribes. Published for the American Folk-Lore Society by G.E. Stechert & Co. Available online through the Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Boas, Franz, and Alexander Francis Chamberlain. 1918. Kutenai Tales. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Carriker, Robert C. 1973. The Kalispel People. Phoenix, AZ: Indian Tribal Series.

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation. 1979. A Brief History of the Flathead Tribes. St. Ignatius, Mont: Flathead Culture Committee, Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes.

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation. 1996. Names Upon the Land, a Tribal Geography of the Salish and Pend D'Oreille People. Pablo, MT: The Committee.

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. 1997. Ktunaxa Legends. Pablo, MT: Salish Kootenai College Press. ISBN 0295976608.

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. 2005. The Salish People and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803243111.

- Curtis, Edward S. [1911] 2003. "Kalispel." The North American Indian, Volume 7. 51. Northwestern University, Digital Library Collections (original Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press). Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Fahey, John. 1986. The Kalispel Indians. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806120002.

- Finley, Debbie Joseph, and Howard Kallowat. 1999. Owl's Eyes & Seeking a Spirit: Kootenai Indian Stories. Pablo, MT: Salish Kootenai College Press. ISBN 0917298667.

- Johnson, Olga Weydemeyer. 1969. Flathead and Kootenay; The Rivers, the Tribes, and the Region's Traders. Glendale, CA: A.H. Clark Co.

- Lacy, Thomas F. 1994. Kaniksu, Stories of the Northwest. Keokee Company Publishing. ISBN 1879628066.

- Lewis, Meriwether, and William Clark. 2002. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13-Volume Set. Edited by Gary E. Moulton. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803229488.

- Linderman, Frank Bird, and Celeste River. 1997. Kootenai Why Stories. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0585315841.

- Mooney, James. 1909. Flathead Indians The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Mooney, James. 1910a. Kalispel Indians The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Mooney, James. 1910b. Kutenai Indians The Catholic Encyclopedia New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Pritzker, Barry M. 2000. A Native American Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195138775

- Prucha, Francis Paul. American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly. University of California Press, 1994. ISBN 0520208951.

- Shea, John Gilmary. [1855] 2008. History Of The Catholic Missions Among The Indian Tribes Of The United States, 1529-1854. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0548997826.

- Tanaka, Béatrice, and Michel Gay. 1991. The Chase: A Kutenai Indian Tale. New York, NY: Crown. ISBN 0517586231.

- Thompson, Steve. St. Ignatius Mission Church | St. Ignatius, Montana National Geographic. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Tyrrell, Joseph Burr (ed.). [1916] 2008. David Thompson's Narrative Of His Explorations In Western America, 1784-1812. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1437017922.

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 0816062730

External links

All links retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes

- Kalispel Tribe of Indians

- Salish World

- Ktunaxa Nation

- Salish Kootenai College

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Confederated_Salish_and_Kootenai_Tribes_of_the_Flathead_Nation history

- Flathead_Indian_Reservation history

- Salish_Kootenai_College history

- Bitterroot_Salish_(tribe) history

- Pend_d'Oreilles_(tribe)256701086 history

- Treaty_of_Hellgate history

- Kaúxuma_Núpika history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 07:50:51 | 69 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Confederated_Salish_and_Kootenai_Tribes_of_the_Flathead_Nation | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF