Plantation

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia In historical terms a plantation was a colony or new settlement in which settlers were "planted" in a new land so as to establish a permanent colonial base or to promote European culture and Christian values. Many of the early settlements of Europeans along the east coast of North America were referred to as plantations; e.g. Roanoke.

Later the term plantation came to mean a large farm or estate in a tropical or semi-tropical countries, used for the growing of coffee, cotton, rubber, sisal, sugar cane, tea, tobacco, etc. and employing resident local or slave labour.

In temperate climes plantation can refer to an area of newly planted woodland.

Contents

18th century America[edit]

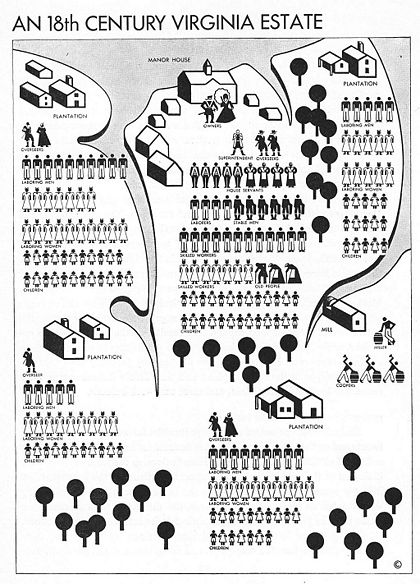

Historians and archaeologists in recent years have rediscovered a great deal about the pre-1800 South.[1] Thomas Jefferson's parents operated Shadwell, a plantation in the 1740-70 period. The Jeffersons led lives of comparative cultural refinement, although Shadwellwas at the extreme western edge of the Virginia frontier. They created a personal "island" of gentrified culture in the Piedmont region, a homestead that virtually replicated the finer domestic accommodations and routines as well as "institutional structures, patterns of slaveholding and agriculture, and slave life" existing in the eastern Tidewater region at the time. Peter Jefferson (father of Thomas) was a successful planter, slaveholder, surveyor, and government officeholder. Jane (the mother of Thomas) was the educated daughter of a successful merchant; they shared a value system that focused their energy and talents on financial success and acquiring status. Shadwell's proximity to the Rivanna River, physical layout, main house and outbuilding construction, household furnishings, and the documentary record of the family's domestic and business activities reveal an extraordinary blend of rugged individualism and the social expectations of the planter class.Plantation System in South[edit]

The ante-bellum economy was dominated by plantations owned by rich white families and using slave labor. Historians define a plantation as having 20 or more slaves (of all ages). Cotton was the main crop in a broad swath (called the "Black Belt") that included most of the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas and Texas. Other plantations grew tobacco (in Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina and Kentucky), hemp (Kentucky and Missouri), rice (South Carolina) or sugar (Louisiana). Most slaves were owned by plantations, and slave culture has been extensively studied. The great majority of whites did NOT live on plantations, and farmed on a smaller scale or on a subsistence scale. The plantation South had few large cities; the most notable were Charleston, SC, and Natchez, Mississippi. In general the plantation owners invested all their profits in new lands and new slaves.

The system survived the Civil War, as the emanciapted Freedmen continued to work on plantation land, as hired hands, tenents or sharecroppers. Aiken (1998) notes the plantation after 1865 had scattered sharecropper huts (compared to concentrated location before). There were few towns so plantation owners provided a crossroads central place that provided a "furnish" store (to advance tenants seed, tools, food staples, against their share of the harvest) and other town-like services. The blacks set up their own Baptist and Methodist churches; the preachers became both religious and political leaders.

The system of cotton plantations collapsed in the 1940s as cotton picking machines drastically reduced the need for labor.[2]

Plantation Historiography[edit]

Anderson (2005) shows that after the Civil War a wave of nostalgia created an image of the plantation South that endured for a century, most notably typified in the novel and movie, "Gone with the Wind" (1939). Memoirs and fiction by former white plantation residents indicate "that nostalgia occurs most forcibly after a profound split in remembered events and experiences." These literary strategies "reveal a potent change in elite white southern consciousness after the Civil War." By 1900, plantation reminiscences that described the Old South as a place of wealth, self-sufficiency, honor, hospitality, and happy master-slave relationships had gained regional, national, and international popularity. The nostalgic memories of Southerners helped them triumph over defeat and create a sense of continuity with the splintered past.

Serious scholarship began in 1900 with Ulrich B. Phillips. He studied slavery not so much as a political issue between North and South but as a social and economic system. He focused on the large plantations that dominated the South.

Phillips's addressed the unprofitability of slave labor and slavery's ill effects on the southern economy. Phillips systematically hunted down and opened plantation and other southern manuscript sources. An example of pioneering comparative work was "A Jamaica Slave Plantation" (1914). His methods inspired the "Phillips school" of slavery studies between 1900 and 1950.

Phillips argued that large-scale plantation slavery was inefficient and not progressive. It had reached its geographical limits by 1860 or so, and therefore eventually had to fade away (as happened in Brazil). In 1910, he argued in "The Decadence of the Plantation System" that slavery was an unprofitable relic that persisted because it produced social status, honor, and political power (that is, Slave Power).

Phillips contended that masters treated slaves relatively well and his views were rejected most sharply by neoabolitionist historian Kenneth M. Stampp in the 1950s. However, Marxist historian Eugene Genovese revived many of Phillips' ideas in the 1960s. Phillips' economic conclusions about the decline of slavery were challenged by Robert Fogel in the 1960s, who argued that slavery was both efficient and profitable as long as the price of cotton was high enough. In turn Fogel came under attack.

Bibliography[edit]

- Aiken, Charles S. The Cotton Plantation South Since the Civil War Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998; geographical study

- Anderson, David. "Down Memory Lane: Nostalgia for the Old South in Post-civil War Plantation Reminiscences." Journal of Southern History 2005 71(1): 105-136. Issn: 0022-4642 Fulltext: in Ebsco and online edition

- Camp, Stephanie M. H. Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women & Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. U. of North Carolina Press, 2004. 206 pp.

- Fox-Genovese, Elizabeth. Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South UNC Press, 1988 online edition

- Genovese, Eugene, Roll, Jordan Roll (1975), the most important recent study.

- Isaac, Rhys. Landon Carter's Uneasy Kingdom: Revolution and Rebellion on a Virginia Plantation (2004), re: late 18th century

- Kern, Susan. "The Material World of the Jeffersons at Shadwell." William and Mary Quarterly 2005 62(2): 213-242. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext: at History Cooperative

- Kulikoff, Allan. Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800 (1986) excerpt and text search

- Lowe, Richard G. and Randolph B. Campbell, Planters and Plain Folk: Agriculture in Antebellum Texas (1987)

- McBride, David. "'Slavery as it Is': Medicine and Slaves of the Plantation South." Magazine of History 2005 19(5): 36-39. Issn: 0882-228x Fulltext in Ebsco

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (1975).

- Phillips, Ulrich B. American Negro Slavery; a Survey of the Supply, Employment, and Control of Negro Labor, as Determined by the Plantation Regime. (1918; reprint 1966)online at Project Gutenberg

- Phillips, Ulrich B. Life and Labor in the Old South. (1929).

- Phillips, Ulrich B. "The Economic Cost of Slaveholding in the Cotton Belt," Political Science Quarterly 20#2 (Jun., 1905), pp. 257–275 in JSTOR

- Phillips, Ulrich B. "The Origin and Growth of the Southern Black Belts." American Historical Review, 11 (July, 1906): 798-816. in JSTOR

- Phillips, Ulrich B. "The Decadence of the Plantation System." Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 35 (January, 1910): 37-41. in JSTOR

- Reidy, Joseph P. From Slavery to Agrarian Capitalism in the Cotton Plantation South: Central Georgia, 1800-1880 UNC Press, 1992 online edition

- Rothman, Adam. Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South (2005),

- Ruef, Martin. "The Demise of an Organizational Form: Emancipation and Plantation Agriculture in the American South, 1860-1880." American Journal of Sociology 2004 109(6): 1365-1410. Issn: 0002-9602 Fulltext: at Ebsco

- Savitt, Todd L. "Black Health on the Plantation: Owners, the Enslaved, and Physicians." Magazine of History 2005 19(5): 14-16. Issn: 0882-228x Fulltext in Ebsco

- Stampp, Kenneth M. The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-bellum South (1956)

- Virts, Nancy. "Change in the Plantation System: American South, 1910-1945." Explorations in Economic History 2006 43(1): 153-176. Issn: 0014-4983

References[edit]

Categories: [Agriculture] [Slavery] [United States History] [The South] [Colonial America] [Early National U.S.] [Farmers]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/15/2023 05:34:07 | 45 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Plantation | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF