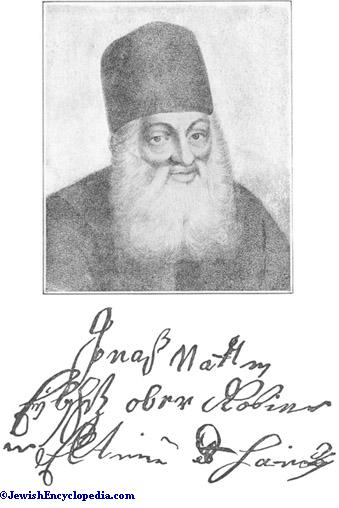

Eybeschütz, Jonathan (Or Eybeschitz)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) Eybeschütz, Jonathan (Or Eybeschitz):

German rabbi and Talmudist; born in Cracow about the year 1690; died in Altona Sept. 18, 1764. His father, Nathan (Nata), who was a grandson of the cabalistic author Nathan Spira, was called as rabbi to Elbenschitz, Moravia, about 1700, where he died about 1702 in early manhood (on the conflicting reports in regard to the date of his death see Dembitzer, "Kelilat Yofi," pp. 118 et seq. , Cracow, 1888). Jonathan was then sent to the yeshibah of Meïr Eisenstadt, who was then rabbi of Prossnitz, and later to the yeshibah of Holleschau, where a relative, Eliezer ha Levi Oettingen, was rabbi. After the latter's death (1710) Eybeschütz went to Vienna, where Samson Wertheimer intended to marry him to his daughter. He thence went to Prague, where he married Elkele, daughter of Rabbi Isaac Spira; and later on he resided two years at Hamburg in the house of Mordecai ha-Kohen, his wife's maternal grandfather. About 1714 he returned to Prague, where he became preacher, probably in succession to Asher Spira, who died in that year (Hock, "Die Familien Prags," p. 381, Presburg, 1892). Here he soon became popular (see Nehemiah Reischer's letter to Jacob Emden, in the latter's "Sefat Emet," p. 11b, Lemberg, 1877); but he also incurred the enmity of some of the family and admirers of the former rabbi, Abraham Broda ("Bene Ahubah," 15b; see Dembitzer, ib. p. 120a), among them being Jacob Reischer, and David Oppenheimer, chief rabbi of Prague. These personal animosities were most likely responsible for the fact that about 1725 Jonathan was accused of sympathy with the followers of Shabbethai Ẓebi, who were still very active. Jonathan took an oath that the accusation was false, and with the other members of the Prague rabbinate signed the excommunication of the followers of Shabbethai Ẓebi.

Believing that his prospects in Prague were poor, he made an effort, upon the death of Jacob Reischer (1733), to secure the rabbinate of Metz. On this occasion he failed, but after Jacob Joshua, who had succeeded Reischer, had gone to Frankfort-on-the-Main, Eybeschütz again became a candidate, and was elected (1741). But in Metz, as in Prague, his congregation divided into enthusiastic admirers and bitter enemies. When in 1746 he was elected rabbi by the congregation of Fürth, the Metz congregation would not release him from his contract. In 1750 he became chief rabbi of Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbeck.

From that time he became a central figure in Jewish history. Shortly after his arrival in Altona a rumor began to spread that he still believed in the Messianic mission of Shabbethai Ẓebi. In substantiation of this charge a number of "ḳeme'ot" (

see Amulet

) were produced which, it was alleged, he had given to sick people in Metz and Altona, and the text of which, though partly in cipher, admitted of no other explanation than that given by his enemies. The inscription read substantially as follows: "In the name of Jahve, the God of Israel, who dwelleth in the beauty of His strength, the God of His anointed one Shabbethai Ẓebi, who with the breath of His lips shall slay the wicked, I decree andcommand that no evil spirit plague, or accident harm, the bearer of this amulet" (Emden, "Sefat Emet," beginning). These amulets were brought to Jacob Emden, who claimed to have been ignorant of the accusations, although they had been for several months the gossip of the congregation. In his private synagogue, which was in his house, he declared that while he did not accuse the chief rabbi of this heresy, the writer of these amulets was evidently a believer in Shabbethai Ẓebi (Feb. 4, 1751). The trustees of the congregation, who sided with their rabbi, at once gave orders to close Jacob Emden's synagogue. Emden wrote to his brother-in-law,

However, the trustees of the Altona congregation declared Emden a disturber of the peace, against whom drastic measures should be taken; and the followers of Eybeschütz assumed such a threatening attitude that Emden was compelled to flee to Amsterdam (May 22, 1751). There he brought charges against his enemies before the Danish courts, with the result that the congregation of Altona was ordered to stop all proceedings against him. In Hamburg the conflict assumed such proportions that the Senate issued strong orders to make an end of the troubles, which were disturbing the public peace (May 1, 1752, and Aug. 10, 1753; see "Allg. Zeit. des Jud." 1858, pp. 520 et seq. ). Emden returned to Altona Aug. 3, 1752; and in December of the same year the courts ordered that nothing should be published concerning the amulets. Meanwhile Eybeschütz's popularity had waned; the Senate of Hamburg suspended him, and many members of that congregation demanded that he should submit his case to rabbinical authorities. "Kurze Nachricht von dem Falschen Messias Sabbathai Zebhi," etc. (Wolfenbüttel, 1752), by Moses Gershon ha-Kohen (Carl Anton ), a convert to Christianity, but a former disciple of Eybeschütz, was evidently an inspired apology. Emden and his followers, in spite of the royal edict, published a number of polemical pamphlets, and Eybeschütz answered in his "Luḥot 'Edut" (1755), which consists of a long introduction by himself, and a number of letters by his admirers denouncing as slanders the accusations brought against him.

His friends, however, were most numerous in Poland, and the Council of Four Lands excommunicated all those who said anything derogatory to the rabbi. A year after the publication of the "Luḥot 'Edut" he was recognized by the King of Denmark and the Senate of Hamburg as chief rabbi of the united congregations of Hamburg-Altona-Wandsbeck. From that time on, respected and beloved, he lived in peace. His enemy Emden testifies to the sincere grief of the congregation at the death of Eybeschütz ("Megillat Sefer," p. 208). Even the notorious extravagances and the subsequent failure in business of his youngest son, Wolf, seem not to have affected the high esteem in which the father was held.

Eybeschütz's memory was revered not only by his disciples, some of whom, like Meshullam Zalman ha-Kohen, rabbi of Fürth, became prominent rabbis and authors, but also by those who were not under personal obligations to him, such as Mordecai Benet, who speaks in the most enthusiastic terms of him in his approbation to the "Bene Ahubah," and Moses Sofer, who tries to defend him in a case where he committed a very bad blunder (atam Sofer, Yoreh De'ah, No. 69). With regard to Eybeschütz's actual attitude toward the Shabbethai Ẓebi heresy, it is difficult to say how far the suspicions of his enemies were justified. On the one hand it can not be denied that the amulets which he wrote contain expressions suggestive of belief in the Messiahship of Shabbethai Ẓebi; but on the other hand it is strange that the accusations came only from jealous enemies. Jacob Emden himself speaks of a rumor to the effect that even before Eybeschütz went to Altona he (Emden) had expressed himself in terms which showed a determination to persecute the successor of his father in the office of chief rabbi ("Megillat Sefer," p. 176); and although he indignantly denies this rumor, he speaks in another place of the chief rabbinate of Altona as "the heritage of my fathers" ( ib. p. 209).

Eybeschütz's works, given in the order of their publication, are as follows:

- 1755. Luhot 'Edut. Altona.

- 1765. Kereti u-Peleti, novellæ on Shulḥan 'Aruk, Yoreh De'ah. Altona.Taryag Miẓwot, the 613 commandments in rimed acrostics. Prague.

- 1773. Tif'eret Yisrael, notes on the rabbinical laws regarding menstruation, with additions by the editor, Israel, grandson of the author and rabbi of Lichtenstadt.

- 1775. Urim we-Tummim, novellæ to Shulḥan 'Aruk, Ḥoshen Mishpaṭ. Carlsruhe.

- 1779-82. Ya'arot Debash, sermons, edited by his nephew Jacob ben Judah Löb of Wojslaw. Carlsruhe.

- 1796. Binah la-'Ittim, notes on the section of the "Yad" dealingwith the holy days, edited by the author's disciple Hillel of Stampfen. Vienna.

- 1799. Hiddushim 'al Hilkot Yom-Ṭob, edited by Joseph of Troppau. It is in substance the same as the last-named work, but differs from it in wording, and contains in addition Maimonides' text. Both therefore present not a work of the author, but notes taken from his lectures. Berlin.

- 1817. Sar ha-Alef, novellæ on Shulhan 'Aruk, Oraḥ Ḥayyim. Warsaw.

- 1819. Bene Ahubah, on the matrimonial laws in the "Yad," edited by his grandson Gabriel Eybescütz. Prague.

- 1825. Tif'eret Yehonatan, homilies on the Pentateuch (n.d., though 1825 is probably correct). Zolkiev.

- 1862. Perush 'al Pisḳa Ḥad Gadya, a homiletical interpretation of the "Ḥad Gadya." Lemberg.

- 1869. Notes on the Haggadah, edited by Moses Zaloshin. Presburg.

- 1891. Shem 'Olam, letters on the Cabala, edited by A. S. Weissmann. Vienna.

A commentary on Lamentations under the title "Allon Bakut," and homilies on the Pentateuch under the title "Ḳesheṭ Yehonatan," are extant in manuscript in the Bodleian Library (Neubauer, "Cat. Bodl. Hebr. MSS." pp. 50 et seq. ).

- G. Klemperer, Ḥayye Yehonatan: Rabbi Jonathan Eibenschütz;

- eine Biographische Skizze, Prague, 1858 (reprinted in Brandeis' Jüdische Universalbibliothek vols. 91-93, Prague, n.d.);

- Ehrentheil, Jüdische Charakterbilder, Budapest, 1867;

- Isaac Gastfreund, Sefer Anshe Shem, Lyck, 1879;

- J. Cohn, Ehrenrettung des R. Jonathan Eibeschitz;

- ein Beitrag zur Kritik des Grätz'schen Geschichtswerkes, in Sefer 'Ale Siaḥ, Blütter aus der Michael David'schen Stiftung, Hanover, 1870;

- Grätz, Gesch. 3d ed., x. 315 et seq.;

- Fuenn, Keneset Yisrael, pp. 425 et seq.;

- Jacob Emden's autobiography, Megillat Sefer, Warsaw, 1896.

- The bibliography on the controversy between Emden and Eybeschütz is given in Grätz, Gesch. x. 507 et seq.

Categories: [Jewish encyclopedia 1906]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 09/04/2022 18:42:23 | 49 views

☰ Source: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/5471-eibenschutz-jonathan.html | License: Public domain

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF