European Diplomacy

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia This article covers European diplomacy since 1815.

Contents

1815 to 1918[edit]

1815-1900[edit]

1900 to 1914[edit]

1914-1919[edit]

Post 1920[edit]

At Versailles the victorious Allies promoted democracy and self-determination for Central Europe. However the Great Depression of the 1930s caused most of the countries to abandon democracy and become one-party states or dictatorships.

Central Europe between the wars[edit]

Starting in 1919, it was the policy of France to construct a cordon sanitaire (quarantine line) in Eastern Europe that was designed to contain both the Germans and Soviets and their ideologies, which were metaphorically compared to diseases. The crushing of Béla Kun's Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919 by the combined forces of Romania, Czechoslovakia, and France was an early example of an enforcement of the cordon sanitaire. In 1921, France signed a defensive alliance with Poland committing both states to come to each other's aid in the event of one of the powers being attacked by another European power. In 1924, the French signed a similar defensive alliance with Czechoslovakia, in 1926 with Romania and in 1927 with Yugoslavia.

In 1925, the French signed new treaties with Poland and Czechoslovakia, which tightened the levels of military co-operation between the signatory states. In addition, the French tried to turn the Little Entente of Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia which had been set up as an anti-Hungarian alliance in 1921 into an anti-German alliance. In 1921, Poland and Romania signed a defensive alliance. This was as close as Poland came to joining the Little Entente. The French would have preferred to also see Poland a member, but antagonism between Czechoslovakia and Poland doomed the idea.

Beyond the Covenant of the League of Nations, Britain had no defense commitments in Eastern Europe in the 1920s and made clear that they wanted to keep it that way.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, a complicated set of alliances was established amongst the nations of Europe, in the hope of preventing future wars (either with Germany or the Soviet Union).[1]

In 1932 and again in 1934, Poland signed a 10-year non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. Also in 1932, the Soviets signed 10-year non-aggression pacts with Finland, Estonia and Latvia. In January 1934, Germany and Poland signed a 10-year non-aggression pact. In 1935, the Soviets signed treaties of alliance with France and Czechoslovakia. The Soviet-Czechoslovak treaty committed the Soviets to come to the aid of Czechoslovakia if attacked by a neighbor provided France did first.

World War II[edit]

Czechoslovakia[edit]

See also: History of Czechoslovakia#Before WWII (1938 – 1939) and later sections

The term "Western betrayal" was coined after the Munich Conference (1938) when Czechoslovakia was forced to cede part of its area (Sudetenland) to Nazi Germany. Czech politicians joined the newspapers in regularly using the term and it, along with the associated feelings, became a stereotype among Czechs. The Czech terms Mnichov (Munich), Mnichovská zrada (Munich betrayal) and zrada spojenců (betrayal of the allies) were coined at the same time and have the same meaning.

During the post-war 1946 parliamentary campaign, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia argued (with much success) that the historical unreliability of Western allies must be countered by closer relations with the Soviet Union. After the Communist Party seized all power in Czechoslovakia in 1948, the 1938 betrayal was frequently referenced in Communist propaganda. This interpretation of history was official and the only one allowed.

After the Communist Party lost its power in the 1989 Velvet Revolution, official use of the term stopped and historians began to discuss the events.

Poland[edit]

First World War aftermath[edit]

After the First World War, Poland regained independence after 123 years of partitions. While the victorious Western allies proclaimed their support for an independent Poland, they also wanted to weaken Germany and the Soviet Union.

Silesia[edit]

Germany controlled Silesia, an industrial area with a largely Polish populace. Many French and British politicians desired the industrial region of Silesia to remain part of Germany, so that Germany would have an easier time paying the Great War reparations to France and its allies. Britain provided no aid to Poland during the 1921 Silesian Uprisings. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, a plebiscite was to be held to determine which areas of ethnically mixed Silesia were to be ceded to Poland and which were to remain with Germany. In some districts of Upper Silesia, the majority of the people were Polish and opted for Poland; the majority in the rest of Upper Silesia opted for Germany. After the plebiscite, the Germans balked at handing over any part of Upper Silesia, claiming that the Versailles treaty did not call for partitioning Silesia by districts. The German interpretation was that the majority of people in Silesia had chosen Germany and so all of Silesia should remain with Germany. The German view was supported by Britain. In fact, the Versailles Treaty did clearly state that Upper Silesia was to be partitioned by districts after the plebiscite.

In the years immediately after World War One, it was French policy to weaken Germany as much as possible, and though the French did not champion the border that the Poles wanted in Silesia, the French attitude to the Polish cause in regard to the Silesian dispute was markedly pro-Polish and anti-German. Indeed, it was an ultimatum from Paris that compelled the Germans to withdraw their forces from Silesia in June 1921.

Ostensibly, the British view that all of Silesia ought to remain with Germany was based on the belief that it would allow Germany to more easily pay reparations to France; by 1921, London had largely abandoned any claims against Germany and was strongly pressuring both France and Belgium to lower their reparations claims against the Germans as much as possible. The British argument about reparations was mostly a bid to influence French public opinion; the real reason for London's pro-German stance was the belief that if Germany were to lose too much territory, this could undermine the fragile Weimar Republic and lead to extremists taking power in Germany. Thus, British policy towards Silesia in 1921 was largely motivated by the desire to consolidate German democracy. Though the British were prepared to support an interpretation of Versailles that violated both its letter and its spirit, and though the Poles were understandably angry with London's pro-German view in this matter, it is very hard to refer to British refusal to support the Polish rebels in Silesia as a “betrayal” as Britain had never made any commitments to do so.

During the Polish-Soviet War (1918-1921), there was a debate among western politicians which side they should support: the White Russians (representing the former Imperial Russia loyalists), the new Bolshevik revolutionaries, or newly independent countries trying to expand their territory at the expense of the powers that lost the First World War. Eventually, France and Britain decided to support the White Russians and Poland; however, their support to Poland was limited to the few hundred soldiers of the French military mission. Further, when it seemed likely in early 1920 that Poland would lose the war (which did not happen), Western diplomats encouraged Poland to surrender and settle for large territorial losses (the Curzon line).

In July 1920, Britain announced it would send huge quantities of World War One surplus military supplies to Poland, but a threatened general strike by the Trades Union Congress who objected to British support of "White Poland" ensured that none of the weapons that were supposed to go to Poland went any further than British ports. The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George had never been enthusiastic about supporting the Poles, and had been pressured by his more right-wing Cabinet members such as Lord Curzon and Winston Churchill into offering the supplies. The threatened general strike was for Lloyd George a convenient excuse for backing out of his commitments. The French were hampered in their efforts to supply Poland by the refusal of Gdańsk (now in Poland) dockworkers to unload supplies for Poland. Likewise, French efforts to supply Poland via land were hindered by the refusal of Czechoslovakia and Germany (both which had border disputes with Poland) to allow arms for Poland to cross their frontiers.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, a complicated set of alliances was established amongst the nations of Europe, in the hope of preventing future wars (either with Germany or Soviet Russia). With the rise of Nazism in Germany, this system of alliances was strengthened by the signing of a series of "mutual assistance" alliances between France, Britain, and Poland. This agreement stated that in the event of war the other allies were to fully mobilize and carry out a "ground intervention within two weeks" in support of the ally being attacked.

Up to 1939[edit]

Diplomacy[edit]

In the years following the end of World War I and the Polish-Soviet War, Poland had signed alliances with many European powers. The most important were the military alliance with France signed on February 19, 1921 and the defensive alliance with Romania of March 3, 1921. The alliance with France was a major factor in Polish inter-war foreign relations, and was seen as the main warrant of peace in Central Europe; Poland's military doctrine was heavily influenced by this alliance as well.

As World War II was nearing, both governments started to look for a renewal of the bilateral promises. This was accomplished in May 1939, when General Tadeusz Kasprzycki signed a secret protocol (later ratified by both governments) to the Franco-Polish Military Alliance with General Maurice Gamelin. It was agreed that France would grant her eastern ally a military credit as soon as possible. In case of war with Germany, France promised to start minor land and air military operations at once, and to start a major offensive (with the majority of its forces) not later than 15 days after the declaration of war.

On March 30, 1939, the British government pledged to defend Poland, in the event of a German attack. The British “guarantee” of Poland was only of Polish independence, and pointly excluded Polish territorial integrity. Britain hoped to prevent Hitler from expanding easterwards, and obtaining control of the resources of Central Europe, which would enable him to turn upon the Western countries with overwhelming force. The basic goal of British foreign policy between 1919-1939 was to prevent another world war by a mixture of “carrot and stick”. The “stick” in this case was the “guarantee” of March 1939, which was intended to prevent Germany from attacking either Poland or Romania. At the same time, the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and his Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax hoped to offer a “carrot” to Adolf Hitler in the form of another Munich-type deal that would see the Free City of Gdańsk (now Poland) and the Polish Corridor returned to Germany in exchange for a promise by Hitler to leave the rest of Poland alone.

This declaration was further amended in April, when Poland and Britain signed a mutual assistance treaty. Like the “guarantee” of March 30, the Anglo-Polish alliance committed Britain only to the defense of Polish independence. It was clearly aimed against German aggression. In case of war, Britain was to start hostilities as soon as possible; initially helping Poland with air raids against the German war industry, and joining the struggle on land as soon as the British army arrived in France. In addition, a military credit was granted and armament was to reach Polish or Romanian ports in early autumn.

At the same time secret German-Soviet talks were held in Moscow which resulted in signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact on August 22, 1939—a decisive event that signaled the war would start soon.

The Phony War[edit]

Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Britain and France declared war on Germany after ultimatums to withdraw expired on September 3. Britain and France enforced a naval blockade on Germany and seized German ships starting with the declaration of war.

A French offensive in the Rhine river valley area (the "Saar Offensive") was immediately launched against Germany. Eleven French divisions advanced along a 32 km line with negligible German opposition. Britain conducted a number of air raids against the German navy on September 4, 1939.

The Allied attitude towards Poland in 1939 has been a subject of an ongoing dispute among historians ever since. Some historians argue that if only France had pursued the offensive against Germany, it would have been able to break through the unfinished Siegfried Line and force Germany to fight a costly two-front war. Others argue that France and Britain had promised more than they would deliver — especially when confronted with the option to declare war on the Soviet Union for violating Poland's territory on September 17, 1939 the way they had on Germany on September 3, 1939 — and that the French army was superior to the Wehrmacht in numbers only. It lacked the offensive doctrines, mobilization schemes, and offensive spirit necessary to attack Germany.

The problem with Polish expectations was that the French and British commitments greatly exaggerated their capabilities. Although France promptly declared war, the French mobilization was not complete until early October, by which time Poland had fallen. In Britain where mobilization was more rapid, only 1 in 40 men were mobilized (compared to 1 in 10 in France, and 1 in 20 in Poland), thus providing only a token force against Germany's forces of several million. After the war, General Alfred Jodl commented that the Germans survived 1939 "only because approximately 110 French and English divisions in the West, which during the campaign on Poland were facing 25 German divisions, remained completely inactive."

In the end, many Poles believe that although Poland held out for five weeks, three weeks longer than was planned, it received no military aid from its allies, Britain and France. Additionally Poland never surrendered to either the Germans or Russians. The agreed upon "two week ground response" never materialized, and Poland fell to the Nazis and the Soviets as a result.

1940s[edit]

Soon after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Polish government in exile signed a pact with Joseph Stalin. Stalin refused to consider any suggestion that he surrender the Polish territory he seized in 1939. Britain nonetheless pressured the Poles to withdraw this demand, since, in Churchill's words, "We could not force our new and sorely threatened [Soviet] ally to abandon, even on paper, regions on her frontier which she regarded for generations as vital to her security." The London Poles conceded but only after Britain agreed to state in writing that all agreements that adjusted Poland's pre-war borders were null and void. The Soviet-Polish agreement was signed on July 30, 1941, and Anthony Eden formally notified the House of Commons of the arrangements that same day. In response to a parliamentary question about Britain's commitment, however, Eden stated that "The exchange of notes which I have just read to the House does not involve any guarantee of frontiers by His Majesty's Government."

The Poles were more successful in obtaining Soviet agreement to the creation of the Polish Army in the East, and obtaining the release of Polish citizens from the Soviet labor camps. Despite the difficulties the Soviet government made, many were freed from confinement and permitted to join the Polish Army formed formally on August 12, 1941. However, after the troops were withdrawn to the Middle East in March 1942, Stalin revoked the amnesty and in June and July arrested all Polish diplomats in the USSR.

Meanwhile, on September 24, 1941, Poland and the Soviet Union signed the Atlantic Charter. It underlined that no territorial changes should be made that would not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned. It was viewed by the Polish government as a warrant of Poland's borders, although it became apparent that some concessions would have to be made.

In December 1941, a Conference was held in Moscow between the USSR and Great Britain. Stalin proposed to base post-war Polish western borders on the Oder-Neisse Line and demanded that the United Kingdom accept the pre-war western borders of the Soviet Union. Anthony Eden accepted the demand as he assumed that the border in question was the 1939 line.[Citation Needed] However, Stalin apparently meant the 1941 border with Germany. It was soon discovered, but the British government decided not to change the document. On March 11, 1942, Winston Churchill notified Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski that the borders of the Baltic States and Romania were guaranteed, and that no decision was made regarding the borders of Poland.

Katyn and the Soviet pressure[edit]

From the very beginning of Polish-Soviet talks in 1941, the government of Poland was searching for approximately 20,000 Polish officers missing in Russia. Stalin always replied that they either must have fled to Mongolia or are somewhere in Russia, which is a big country and it's easy to get lost here[Citation Needed]. In April 1943 German news agencies reported finding mass graves of Polish soldiers in Katyn. The Polish government requested the Soviet Union examine the case and at the same time asked the International Red Cross for help in verifying the German reports.

On April 24, 1943, Sikorski met with Eden and demanded Allied help in releasing Polish prisoners in the gulags and Soviet prisons. Sikorski also declined the Soviet demand that Poland withdraw their plea to have the Red Cross investigate Katyn. Anthony Eden refused to help and the Soviet Union broke diplomatic relations with Poland on the following day, arguing that the Polish government was collaborating with Nazi Germany. Despite Polish pleas for help, the United States and the United Kingdom decided not to put pressure on the USSR.

After the Soviets stopped the German advance on the Eastern Front, Poland lost its significance as the main Eastern ally. This was made obvious by the German defeat at Stalingrad.

Tehran[edit]

- See also: Teheran conference

In November 1943, the Big Three (USSR, USA, and UK) met at the Tehran Conference. Both Roosevelt and Churchill officially agreed that the eastern borders of Poland would roughly follow the Curzon Line. That meant that Western Ukraine would become part of the Ukraine (and thus part of the Soviet Union). Few Poles lived therebut they did not want to gove it up. and Roosevelt did not wish to upset Polish voters in the United States during the upcoming Presidential elections of 1944.[2]

1944 Warsaw Uprising[edit]

Since the establishment of the Polish government in exile, the military commanders of the Polish army were focusing most of their efforts on preparation of a future all-national uprising against Germany. Finally, the plans for "Operation Tempest" were prepared and on August 1, 1944 the Warsaw Uprising started. The Uprising was an armed struggle by the Polish Home Army to liberate Warsaw from German occupation and Nazi rule. At this point the Russian army was closing in, but it unexpectedly stopped, allowing the Germans to use their full military power to crush the pooly armed revolt. The uprising lasted for over 60 days, from August 1 to early October 1944. The Polish underground army, known as the AK, took on numerically superior and much better-armed Wehrmacht and SS units. The outcome was catastrophic. After the AK surrendered, the Germans evacuated all the inhabitants of Warsaw amid scenes of random murder. In the course of the whole ordeal at least 160,000 Poles, and perhaps many more, were killed. With flamethrowers and dynamite, the Germans then destroyed the deserted city with all its historic landmarks, its cathedral and palaces.

Polish and RAF planes flew missions over Warsaw dropping supplies from 4 August on, the United States did not join the operation. Stalin refused the use of Soviet airfields, and refused any aid to the Warsaw freedom fighters. Any aid would have been symbolic, for the uprising was hopeless without the full commitment of Societ forces.[3]

Yalta[edit]

- See also: Yalta conference.

In 1945, Poland's borders were redrawn following the decision made at the Tehran Conference of 1943 at the insistence of the Soviet Union. The Polish government was not invited to the talks and was to be notified of their outcome. Polish representatives did present arguments concerning borders at the Potsdam conference, however, and Polish demands for German territory were agreed to. The eastern territories which the Soviet Union had occupied in 1939 (with the exception of the Białystok area) were permanently annexed, and most of their Polish inhabitants expelled: today these territories are part of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania. The factual basis of this decision was the result of a forged referendum from November 1939 in which the "huge majority" of voters accepted the incorporation of these lands into Western Belarus and Western Ukraine. In compensation, Poland was given former German territory (the so-called Regained Territories): the southern half of East Prussia and all of Pomerania and Silesia, up to the Oder-Neisse Line. The German population of these territories were deported and these territories were subsequently repopulated with Poles deported from the eastern regions. This combined with other similar migrations in Central Europe to form one of the largest human migrations in modern times. Stalin ordered Polish resistance fighters to be either incarcerated or deported to gulags in Siberia. Many Poles believe that Western leaders tried to force Polish leaders to accept the conditions of Stalin. Some view it as a 'betrayal' of Poland by its Western allies (which can be seen as part of a larger 'betrayal' to 'allow' it to fall entirely into the Soviet sphere of influence).[4] Moreover, it was used by ruling communists to underline anti-Western sentiments.[5][6] It was easy to argue that Poland was not very important to the West, since Allied leaders sacrificed Polish borders, the legal government, and free elections.[7][8][9]

With this background, even Stalin looked more reliable since he did have strong interests in Poland. The Federal Republic of Germany, formed in 1949, was portrayed by Communist propaganda as the breeder of Hitler's posthumous offspring who desired retaliation and wanted to take back from Poland the "Recovered Territories".[10] Giving this picture a grain of creditability was contained in the fact that Federal Republic of Germany until 1970 refused to recognize the Oder-Neisse Line and that many West German officials were alleged to have a tainted Nazi past. Thus, for a segment of Polish public opinion, Communist rule was seen as the lesser of the two evils.

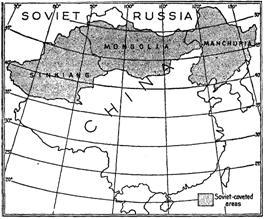

Defenders of the actions taken by the Western allies maintain that Realpolitik made it impossible to do anything else, and that they were in no shape to start an utterly un-winnable war with the Soviet Union over the subjugation of Poland and other Central European countries immediately after the end of World War II. Some argue that the actions of the Secretary of State were a result of ignorance rather than Realpolitik.[Citation Needed] is not aware of the fact." Molotov paused for a reply. No denial was forthcoming.85 The truth was out at last. Later Churchill told Mikolajczyk he "was not going to wreck the peace of Europe because of a quarrel between Poles."[11] It is contended that the presence of a double standard with respect to Nazi and Soviet aggression existed in 1939 and 1940, when the Soviets invaded eastern Poland and the Baltic States, respectively, and the Western Allies failed to declare war. The U.S. State Department never issued a single diplomatic protest against the Soviet Union despite her absorption of Sinkiang and Outer Mongolia, while at the same time, Japan was censured for stationing troops in Manchuria.[12]

What the Western allies sacrificed is also disputed. Some argue that Poland's borders had been re-drawn many times in history, the country had not had free elections since 1926 and throughout the 1930s it had endured increasing political repression under an authoritarian Sanacja government. On the other hand, the Polish government in exile was composed entirely of the pre-war democratic opposition and all political parties of the Polish Secret State underlined the need to follow the democratic traditions of March 1921 constitution, rather than autocratic April constitution of Poland of 1935.

In May 2005 US President George W. Bush admitted that the Soviet domination of Central Europe and the Balkans after World War II was "one of the greatest wrongs of history" and acknowledged that the United States played a significant role in the division of the continent and that the Yalta conference "followed in the unjust tradition of Munich and the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. (...) Once again, when powerful governments negotiated, the freedom of small nations was somehow expendable." In fact, chief American negotiator at Yalta, Alger Hiss, was later found to be secretly working for the Soviets.[13]

Aftermath[edit]

Władysław Sikorski, Prime Minister of Polish Government in Exile, was killed in an air crash over Gibraltar in July 1943. As he was the most prestigious leader of the Polish exiles, his death was a severe setback to the Polish cause, and was certainly highly convenient for Stalin. It was in some ways also convenient for the western Allies, who were finding the Polish issue a stumbling-block in their efforts to preserve good relations with Stalin.

This has given rise to persistent suggestions that Sikorski's death was not accidental. Many historians speculate that his death might have been effect of Soviet, British or even a Polish conspiracy. This has never been proven, and the fact that the principal exponents of this theory in the west have been the revisionist historians David Irving and Rolf Hochhuth has not encouraged many western historians to take it seriously.

On the other hand, by 2000 only a small part of the British Intelligence documents related to Sikorski's death had been unclassified and made available to Polish historians. The majority of the files will be classified for another "50 to 100 years." This is a common procedure in the release of most types of official secret documents in the UK.

In November 1944, despite his mistrust of the Soviets, Sikorski's successor, Prime Minister Stanisław Mikołajczyk resigned to return to Poland and take office in the new government established under the auspices of the Soviet occupation authorities. Many of the Polish exiles opposed this action, believing that this government was a facade for the establishment of Communist rule in Poland, a view that was later proved correct; after losing an election which was later shown to have been fraudulent, Mikołajczyk left Poland again in 1947.

Meanwhile, the government in exile had maintained its existence, but the United States and the United Kingdom withdrew their recognition on July 6, 1945. The Polish armed forces in exile were disbanded in 1945 and most of the exiles, unable to return to Communist Poland, settled in other countries. The London Poles had to leave the embassy on Portland Place and were left only with the president's private residence at 43 Eaton Place. The government in exile then became largely symbolic, serving mainly to symbolize the continued resistance to foreign occupation of Poland, and retaining control of some important archives from pre-war Poland. Ireland and Spain were the last countries to recognize the government in exile.

No representatives of Polish military, veterans of Battle of Britain and Monte Cassino, were invited to the London Victory Parade of 1946 - Poles were supposed to attend the Moscow Victory Parade instead. This was because the Victory Parade was solely for the nations of the British Empire and Commonwealth and no other foreign troops were invited.

At the war's end many of these feelings of resentment were capitalized on by the occupying Soviets, who used them to reinforce anti-Western sentiments within Poland. Propaganda was produced by Communists to show Russia as the Great Liberator, and the West as the Great Traitor.[Citation Needed] Capitalism was shown as being inherently bad, because capitalists only cared for "their own skin," while communism was portrayed as the great "uniter and protector."

Russia[edit]

In the final days of the war, masses of refugees from Nazi-abandoned Russia and Croatia were fleeing from the Red Army and Tito's partisans. In Operation Keelhaul, British troops gathered these thousands of refugees in Austria including Cossacks, Ustase, Croatian and White Russian troops, and civilians. The Soviet and Russian citizens were turned to Soviet-occupied Germany, where in many cases they were summarily shot.

Baltic States[edit]

For the Baltic States, however, who also had their fate sealed by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939, which (after some revision) assigned the Baltics to Soviet control. The U.S. never recognized this annexation and helped the Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania become fully independent in 1991.

Notes and references[edit]

- In-line:

- ↑ In 1933, there were false rumors that a "preventive war" option against Germany was being considered by the French, Belgian and Polish governments.

- ↑ Roosevelt told Stalin, “Next year in the United States elections are in prospect. …In America there are millions of citizens of Polish origin, and therefore, being a practical person, I would not want to lose their concerns. I am agreeable with Marshal Stalin to the fact that we must restore the Polish state, and personally I do not have objections to the borders of Poland being moved from the east to the West - up to Oder, but for political reasons I cannot participate at present in the resolution of this question. I consider Marshal Stalin's ideas, I hope that he will understand, why I cannot publicly participate in resolution of this question." № 63 Memorandum of conversation Josef Stalin with Franklin Roosevelt, Teheran conference, 1 December 1943 Russian text.

- ↑ Norman Davies, Rising '44: The Battle for Warsaw (2004)

- ↑ ‘’The Yalta Betrayal’’, Felix Wittmer, Claxton Printers, 1953, pgs. 12 - 13. “Fact is that Roosevelt, eager to succeed where Woodrow Wilson had failed, dreamed of creating a better and more peaceful world through legal instruments, and in pursuit of his illusions obtruded himself upon Joe Stalin with every imaginable gift, including eleven billion dollars' worth of lend-lease, the security of eighty million eastern Europeans and hundreds of millions of Chinese, and the lives of several millions of the best friends free society possessed.”

- ↑ Samuel Leonard Sharp (1953). Poland, white eagle on a red field. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 163.

- ↑ Norman Davies (2005 [1982]). God's Playground. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12819-3.

- ↑ Howard Jones (2001). Crucible of Power: a history of U.S. foreign relations since 1897. Rowman & Littlefield, 205–207. ISBN 0842029184.

- ↑ various authors (1948). "A compilation of selected resolutions, declarations, memorials, memorandums,...". Selected Documents (Chicago, IL: Polish American Congress) (1244-1248): 112. https://books.google.com/books?id=x5brwE5vmlwC&vid=OCLC05523398&dq=Yalta+free+elections+Poland&q=AS+A+PARTY+TO+THE+YALTA+AGREEMENT+THAT+CRUSHED&pgis=1#search.

- ↑ Sharp, op.cit., p.12

- ↑ "Poland under Stalinism", _Poznan in June 1956: A Rebellious City_, The Wielkopolska Museum of the Fight for Independence in Poznan, 2006, p. 5

- ↑ Jan Ciechanowski, Defeat in Victory, Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1947, pgs. 330-331, quoted in John T. Flynn, The Roosevelt Myth, Fox and Wilkes, 1948, Book 3, Chapter 9, The Great Conferences.

- ↑ Communism at Pearl Harbor, How the Communists Helped to Bring on Pearl Harbor and Open up Asia to Communinization, Dr. Anthony Kubek, Dallas Texas, Teaching Publishing Company, 1959, pg. 22. Dr. Anthony Kubek was the Editor of the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, Report on the Morgenthau Diaries. In 1965, the SISS issued a two volume committee print entitled Morgenthau Diary (China), Edited by Dr. Anthony Kubek, containing entries from the records at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library selected to illustrate the implementation of Roosevelt administration policy in China. According to Dr. Kubek, the subcommittee wanted to produce a documentary history on the subject and "also indicate the serious problem of unauthorized, uncontrolled and often dangerous power exercised by non-elected officials," specifically Harry Dexter White. White was a major figure in Senator William Jenner's investigation of interlocking subversion in Government departments in 1953. [1]

- ↑ Venona 1822 Washington to Moscow, 30 March 1945.

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

19th century[edit]

- Gilpin, Robert. War and Change in World Politics (1981) excerpt and text search

World War I[edit]

- Bakeless, John Edwin. The Economic Causes of Modern War: A Study of the Period: 1878-1918 (1919) online edition

- Cramer, Kevin. "A World of Enemies: New Perspectives on German Military Culture and the Origins of the First World War," Central European History (2006), 39#2 pp 270–298 online at CJO

- Evans, R. J. W., and Hartmut Pogge Von Strandman, eds. The Coming of the First World War (1990), essays by scholars from both sides online edition

- Fay, Sidney. The Origins of the World War (1930); classic scholarly study; argues every nation shared guilt for starting the war online edition

- Fromkin, David. Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?, (2004), ISBN 0375411569.

- Hamilton, Richard F. and Holger H. Herwig, eds. The Origins of World War I, (2003) 553pp; 15 long essays by leading scholars; excerpt and text search

- Hamilton, Richard F. and Holger H. Herwig, eds. Decisions for War, 1914-1917 (2004) ' a condensed version in 282pp

- Henig, Ruth The Origins of the First World War (2002) 76pp online edition

- Hewitson, Mark. Germany and the Causes of the First World War (2004)

- Joll, James. The Origins of the First World War. (3rd ed 2006).

- Kennedy, Paul M. (ed.). The War Plans of the Great Powers, 1880-1914. (1979)

- Kennedy, Paul M. The Rise of the Anglo-German Antagonism, 1860-1914 (1981)

- Lee, Dwight E. ed. The Outbreak of the First World War: Who Was Responsible? (1958), readings from multiple points of view

- Maier, Charles S. "Wargames: 1914-1919" in Rabb T. and Rotberg R. (eds.), The Origins and Prevention of Major Wars, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1989), 249-279

- Miller, Steven E. (ed.) Military Strategy and the Origins of the First World War: an International Security Reader, (1985)

- Page, Thomas Nelson. Italy and the World War (1920) online edition

- Ponting, Clive. Thirteen Days: Diplomacy and Disaster - The Countdown to the Great War (2002)

- Snyder, Jack L. The Ideology of the Offensive. Military Decision Making and the Disasters of 1914. (1984), 267 pp. excerpt and text search

- Stevenson, David. The First World War and International Politics (2005)

- Van Evera, Stephen. Causes of War. Power and the Roots of Conflict. (1998), chap.7, pp 193–239.

- Williamson, Samuel R. Jr. "The Origins of World War I" in Rabb T. and Rotberg R. (eds.), The Origins and Prevention of Major Wars, (1989), 225-248.

- Williamson, Samuel R. The politics of grand strategy: Britain and France prepare for war, 1904-1914 (1990) online at ACLS e-books

- Williamson Jr. Samuel R. and Ernest R. May. "An Identity of Opinion: Historians and July 1914," Journal of Modern History(2007) Volume 79, Number 2, 335-87, historiography online

1920s[edit]

- Craig, Gordon A. and Felix Gilbert, eds. The Diplomats 1919–1939 (1953).

- Cienciala, Anna M. and Titus Komarnicki From Versailles to Locarno: keys to Polish foreign policy, 1919–25, (1984).

- Lukes, Igor, and Erik Goldstein, eds. The Munich crisis, 1938: prelude to World War II, (1999).

- Macmillan, Margaret Olwen. Paris 1919: six months that changed the world (2001). Very well written scholarly study of making of the Treaty of Versailles

1920-1945[edit]

- Adamthwaite, Anthony. Grandeur and Misery: France's Bid for Power in Europe, 1914-40 (1995) 276 pp

- Bell, P.M.H. The Origins of the Second World War in Europe (3rd ed. 2007) good short survey

- Boyce, Robert. French Foreign and Defence Policy, 1918-1940: The Decline and Fall of a Great Power (1998) excerpt and text search

- Deist, Wilhelm et al., ed. Germany and the Second World War. Vol. 1: The Build-up of German Aggression. (1991). 799 pp., official German history

- Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste. France and the Nazi Threat: The Collapse of French Diplomacy 1932-1939 (2004)

- Eubank, Keith. The Origins of World War II (2004), short survey

- Finney, Patrick ed. The Origins of the Second World War (1997)

- Henig, Ruth. The Origins of the Second World War 1933-1939 (2nd ed 2005) short survey excerpt and text search

- Finney, Patrick. The Origins of the Second World War (1998), 480pp

- Goldstein, Erik & Lukes, Igor, eds. The Munich crisis, 1938: Prelude to World War II, (1999)

- Hildebrand, Klaus. The Foreign Policy of the Third Reich, (1973).

- Imlay, Talbot. "Democracy and War: Political Regime, Industrial Relations, and Economic Preparations for War in France and Britain up to 1940." Journal of Modern History 2007 79(1): 1-47. Issn: 0022-2801

- Kaiser, David E. Economic diplomacy and the origins of the Second World War: Germany, Britain, France and Eastern Europe, 1930-1939 (1980)

- Lamb, Margaret and Tarling, Nicholas. From Versailles to Pearl Harbor: The Origins of the Second World War in Europe and Asia. (2001). 238 pp.

- Leitz, Christian. Nazi Foreign Policy, 1933-1941: The Road to Global War (2004) online edition

- Lukes, Igor. The Munich Crisis, 1938: Prelude to World War II (1999), 416pp excerpt and text search

- Mallett, Robert. Mussolini and the Origins of the Second World War, 1933 - 1940 (2003) excerpt and text search

- Overy, Richard. The Road to War (2nd ed. 2000) excerpt and text search

- Overy, Richard and Timothy Mason, "Debate: Germany, 'Domestic Crisis' and War in 1939" Past and Present, Number 122, February 1989. pages 200-240

- Parker, R. A. C. Chamberlain and Appeasement: British Policy and the Coming of the Second World War. (1993). 388 pp.

- Prazmowska, Anita J. Eastern Europe and the Origins of the Second World War. (2000). 278 pp.

- Read, Anthony and Fisher, David. The Deadly Embrace: Hitler, Stalin and the Nazi-Soviet Pact, 1939-1941. (1988). 675 pp.

- Record, Jeffrey. The Specter of Munich: Reconsidering the Lessons of Appeasing Hitler (2006) excerpt and text search

- Rothwell, Victor. War Aims in the Second World War: The War Aims of the Key Belligerents 1939-1945 (2005) excerpt and text search

- Salerno, Reynolds Matthewson. Vital Crossroads: Mediterranean Origins of the Second World War, 1935-1940. (2002). 285 pp.

- Strang, G. Bruce On The Fiery March: Mussolini Prepares For War, (2003) ISBN 0-275-97937-7.

- Taylor, A J P The Origins of the Second World War (1961). 368pp. highhly controversial in Britain

- Tooze, Adam. "Hitler's Gamble?" History Today 2006 56(11): 22-28. Issn: 0018-2753 Fulltext: Ebsco, economic causes

- Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (2007) influential emphasis that Hitler began to rearm in 1933

- Watt, Donald Cameron How War Came: The Immediate Origins of the Second World War, 1938-1939, (1989), a major survey

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II (1994). Overall history of the war; strong on diplomacy of FDR and other main leaders online at ACLS e-books

- Weinberg, Gerhard. The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany: Starting World War II, 1937-1939, (1980) ISBN 0-226-88511-9.

- Young, Robert J. France and the Origins of the Second World War (1996) excerpt and text search

Historiography[edit]

- Boxer, Andrew. "French Appeasement: Andrew Boxer Considers Explanations for France's Disastrous Foreign Policy between the Wars." History Review v. 59 (2007) pp. 45+. online edition

- Boyce, Robert, and Joseph A. Maiolo. The Origins of World War Two: The Debate Continues (2003) excerpt and text search

- Jackson, Peter. "Post-War Politics and the Historiography of French Strategy and Diplomacy Before the Second World War," History Compass Vol. 4, August 2006 online edition

- Martel, Gordon, ed. The Origins of the Second World War Reconsidered: A.J.P. Taylor and the Historians, (2nd ed. 1999) excerpt and text search

- Neville, Peter. "The Origins of the Second World War Revisited." European History Quarterly 2005 35(4): 569-582. Issn: 0265-6914 Fulltext: Ebsco

- Young, Robert J. French Foreign Policy, 1918-1945: A Guide to Research and Research Materials. (1991)

Categories: [European History] [Diplomacy] [World War I] [World War II]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/28/2023 04:13:47 | 245 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/European_Diplomacy | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF