Education

From Nwe

From Nwe | Schools |

|---|

| Education |

| History of education |

| Pedagogy |

| Teaching |

| Homeschooling |

| Preschool education |

| Child care center |

| Kindergarten |

| Primary education |

| Elementary school |

| Secondary education |

| Middle school |

| Comprehensive school |

| Grammar school |

| Gymnasium |

| High school |

| Preparatory school |

| Public school |

| Tertiary education |

| College |

| Community college |

| Liberal arts college |

| University |

Education encompasses teaching and learning specific skills, and also something less tangible but more profound: the imparting of knowledge, positive judgment and well-developed wisdom. Education has as one of its fundamental aspects the imparting of culture from generation to generation (see socialization), yet it more refers to the formal process of teaching and learning found in the school environment.

Education means "to draw out," facilitating the realization of self-potential and latent talents of an individual. It is an application of pedagogy, a body of theoretical and applied research relating to teaching and learning and draws on many disciplines such as psychology, philosophy, computer science, linguistics, neuroscience, sociology and anthropology.

Many theories of education have been developed, all with the goal of understanding how the young people of a society can acquire knowledge (learning), and how those who have knowledge and information that is of value to the rest of society can impart it to them (teaching). Fundamentally, though, education aims to nurture a young person's growth into mature adulthood, allowing them to achieve mastery in whichever area they have interest and talent, so that they can fulfill their individual potential, relate to others in society as good citizens, and exercise creative and loving dominion over their environment.

Etymology

The word "education" has its roots in proto-Indian-European languages, in the word deuk. The word came into Latin in the two forms: educare, meaning "to nourish" or "to raise," and educatus, which translates as education. In Middle English it was educaten, before changing into its current form.[1]

Education history

Education started as the natural response of early civilizations to the struggle of surviving and thriving as a culture. Adults trained the young of their society in the knowledge and skills they would need to master and eventually pass on. The evolution of culture, and human beings as a species depended on this practice of transmitting knowledge. In pre-literate societies this was achieved orally and through imitation. Story-telling continued from one generation to the next. Oral language developed into written symbols and letters. The depth and breadth of knowledge that could be preserved and passed soon increased exponentially. When cultures began to extend their knowledge beyond the basic skills of communicating, trading, gathering food, religious practices, and so forth, formal education, and schooling, eventually followed.

Many of the first educational systems were based in religious schooling. The nation of Israel in c. 1300 B.C.E., was one of the first to create a system of schooling with adoption of the Torah. In India, The Gurukul system of education supported traditional Hindu residential schools of learning; typically the teacher's house or a monastery where the teacher imparted knowledge of Religion, Scriptures, Philosophy, Literature, Warfare, Statecraft, Medicine, Astrology, and History (the Sanskrit word "Itihaas" means History). Unlike in many regions of the world, education in China began not with organized religions, but based upon the reading of classical Chinese texts, which developed during Western Zhou period. This system of education was further developed by the early Chinese state, which depended upon literate, educated officials for operation of the empire, and an imperial examination system was established in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.-220) for evaluating and selecting officials. This merit-based system gave rise to schools that taught the classics and continued in use for 2,000 years.

Perhaps the most significant influence on the Western schooling system was Ancient Greece. Such thinkers as Socrates, Aristotle and Plato along with many others, introduced ideas such as rational thought, scientific inquiry, humanism and naturalism. Yet, like the rest of the world, religious institutions played a large factor as well. Modern systems of education in Europe derive their origins from the schools of medieval period. Most schools during this era were founded upon religious principles with the sole purpose of training the clergy. Many of the earliest universities, such as the University of Paris, founded in 1150 had a Christian basis. In addition to this, a number of secular universities existed, such as the University of Bologna, founded in 1088.

Education philosophy

The philosophy of education is the study of the purpose, nature and ideal content of education. Related topics include knowledge itself, the nature of the knowing mind and the human subject, problems of authority, and the relationship between education and society. At least since Locke's time, the philosophy of education has been linked to theories of developmental psychology and human development.

Fundamental purposes that have been proposed for education include:

- The enterprise of civil society depends on educating young people to become responsible, thoughtful and enterprising citizens. This is an intricate, challenging task requiring deep understanding of ethical principles, moral values, political theory, aesthetics, and economics, not to mention an understanding of who children are, in themselves and in society.

- Progress in every practical field depends on having capacities that schooling can educate. Education is thus a means to foster the individual's, society's, and even humanity's future development and prosperity. Emphasis is often put on economic success in this regard.

- One's individual development and the capacity to fulfill one's own purposes can depend on an adequate preparation in childhood. Education can thus attempt to give a firm foundation for the achievement of personal fulfillment. The better the foundation that is built, the more successful the child will be. Simple basics in education can carry a child far.

A central tenet of education typically includes “the imparting of knowledge.” At a very basic level, this purpose ultimately deals with the nature, origin and scope of knowledge. The branch of philosophy that addresses these and related issues is known as epistemology. This area of study often focuses on analyzing the nature and variety of knowledge and how it relates to similar notions such as truth and belief.

While the term, knowledge, is often used to convey this general purpose of education, it can also be viewed as part of a continuum of knowing that ranges from very specific data to the highest levels. Seen in this light, the continuum may be thought to consist of a general hierarchy of overlapping levels of knowing. Students must be able to connect new information to a piece of old information to be better able to learn, understand, and retain information. This continuum may include notions such as data, information, knowledge, wisdom, and realization.

Education systems

Schooling occurs when society or a group or an individual sets up a curriculum to educate people, usually the young. Schooling can become systematic and thorough. Sometimes education systems can be used to promote doctrines or ideals as well as knowledge, and this can lead to abuse of the system.

Preschool education

Preschool education is the provision of education that focuses on educating children from the ages of infancy until six years old. The term preschool educational includes such programs as nursery school, day care, or kindergarten, which are occasionally used interchangeably, yet are distinct entities.

The philosophy of early childhood education is largely child-centered education. Therefore, there is a focus on the importance of play. Play provides children with the opportunity to actively explore, manipulate, and interact with their environment. Playing with products made especially for the preschool children helps a child in building self confidence, encourages independent learning and clears his concepts. For the development of their fine and large or gross motor movements, for the growth of the child's eye-hand coordination, it is extremely important for him to 'play' with the natural things around him. It encourages children to investigate, create, discover and motivate them to take risks and add to their understanding of the world. It challenges children to achieve new levels of understanding of events, people and the environment by interacting with concrete materials.[2] Hands-on activities create authentic experiences in which children begin to feel a sense of mastery over their world and a sense of belonging and understanding of what is going on in their environment. This philosophy follows with Piaget's ideals that children should actively participate in their world and various environments so as to ensure they are not 'passive' learners but 'little scientists' who are actively engaged.[3]

Primary education

Primary or elementary education consists of the first years of formal, structured education that occur during childhood. Kindergarten is usually the first stage in primary education, as in most jurisdictions it is compulsory, but it is also often associated with preschool education. In most countries, it is compulsory for children to receive primary education (though in many jurisdictions it is permissible for parents to provide it). Primary education generally begins when children are four to eight years of age. The division between primary and secondary education is somewhat arbitrary, but it generally occurs at about eleven or twelve years of age (adolescence); some educational systems have separate middle schools with the transition to the final stage of secondary education taking place at around the age of fourteen.

Secondary education

In most contemporary educational systems of the world, secondary education consists of the second years of formal education that occur during adolescence. It is characterized by transition from the typically compulsory, comprehensive primary education for minors to the optional, selective tertiary, "post-secondary," or "higher" education (e.g., university, vocational school) for adults. Depending on the system, schools for this period or a part of it may be called secondary or high schools, gymnasiums, lyceums, middle schools, colleges, or vocational schools. The exact meaning of any of these varies between the systems. The exact boundary between primary and secondary education varies from country to country and even within them, but is generally around the seventh to the tenth year of education. Secondary education occurs mainly during the teenage years. In the United States and Canada primary and secondary education together are sometimes referred to as K-12 education. The purpose of secondary education can be to give common knowledge, to prepare for either higher education or vocational education, or to train directly to a profession.

Higher education

Higher education, also called tertiary, third stage or post secondary education, often known as academia, is the non-compulsory educational level following the completion of a school providing a secondary education, such as a high school, secondary school, or gymnasium. Tertiary education is normally taken to include undergraduate and postgraduate education, as well as vocational education and training. Colleges and universities are the main institutions that provide tertiary education (sometimes known collectively as tertiary institutions). Examples of institutions that provide post-secondary education are community colleges (Junior colleges as they are sometimes referred to in parts of Asia and Africa), vocational schools, trade or technology schools, colleges, and universities. They are sometimes known collectively as tertiary or post-secondary institutions. Tertiary education generally results in the receipt of certificates, diplomas, or academic degrees. Higher education includes teaching, research and social services activities of universities, and within the realm of teaching, it includes both the undergraduate level (sometimes referred to as tertiary education) and the graduate (or postgraduate) level (sometimes referred to as graduate school).

In most developed countries a high proportion of the population (up to 50 percent) now enter higher education at some time in their lives. Higher education is therefore very important to national economies, both as a significant industry in its own right, and as a source of trained and educated personnel for the rest of the economy. However, countries that are increasingly becoming more industrialized, such as those in Africa, Asia and South America, are more frequently using technology and vocational institutions to developed a more skilled work-force.

Adult education

Lifelong, or adult, education has become widespread in many countries. However, education is still seen by many as something aimed at children, and adult education is often branded as adult learning or lifelong learning. Adult education takes on many forms, from formal class-based learning to self-directed learning.

Lending libraries provide inexpensive informal access to books and other self-instructional materials. The rise in computer ownership and internet access has given both adults and children greater access to both formal and informal education.

In Scandinavia a unique approach to learning termed folkbildning has long been recognized as contributing to adult education through the use of learning circles. In Africa, government and international organizations have established institutes to help train adults in new skills so that they are to perform new jobs or utilize new technologies and skills in existing markets, such as agriculture.[4]

Alternative education

Alternative education, also known as non-traditional education or educational alternative, is a broad term which may be used to refer to all forms of education outside of traditional education (for all age groups and levels of education). This may include both forms of education designed for students with special needs (ranging from teenage pregnancy to intellectual disability) and forms of education designed for a general audience which employ alternative educational philosophies and/or methods.

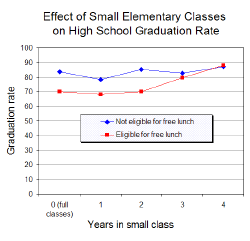

Alternatives of the latter type are often the result of education reform and are rooted in various philosophies that are commonly fundamentally different from those of traditional compulsory education. While some have strong political, scholarly, or philosophical orientations, others are more informal associations of teachers and students dissatisfied with certain aspects of traditional education. These alternatives, which include charter schools, alternative schools, independent schools, and home-based learning vary widely, but often emphasize the value of small class size, close relationships between students and teachers, and a sense of community.

Education technology

Technology is an increasingly influential factor in education. Computers and mobile phones are being widely used in developed countries both to complement established education practices and develop new ways of learning such as online education (a type of distance education). This gives students the opportunity to choose what they are interested in learning. The proliferation of computers also means the increase of programming and blogging. Technology offers powerful learning tools that demand new skills and understandings of students, including Multimedia literacy, and provides new ways to engage students, such as classroom management software.

Technology is being used more not only in administrative duties in education but also in the instruction of students. The use of technologies such as PowerPoint and interactive whiteboard is capturing the attention of students in the classroom. Technology is also being used in the assessment of students. One example is the Audience Response System (ARS), which allows immediate feedback tests and classroom discussions.

The use of computers and the Internet is still in its infancy in developing countries due to limited infrastructure and the attendant high costs of access. Usually, various technologies are used in combination rather than as the sole delivery mechanism. For example, the Kothmale Community Radio Internet uses both radio broadcasts and computer and Internet technologies to facilitate the sharing of information and provide educational opportunities in a rural community in Sri Lanka.[5]

Education psychology

Educational psychology is the study of how humans learn in educational settings, the effectiveness of educational interventions, the psychology of teaching, and the social psychology of schools as organizations. Although the terms "educational psychology" and "school psychology" are often used interchangeably, researchers and theorists are likely to be identified as educational psychologists, whereas practitioners in schools or school-related settings are identified as school psychologists. Educational psychology is concerned with the processes of educational attainment in the general population and in sub-populations such as gifted children and those with specific learning disabilities.

There was a great deal of work done on learning styles over the last two decades of twentieth century. Rita Stafford Dunn and Kenneth J. Dunn focused on identifying relevant stimuli that may influence learning and manipulating the school environment.[7] Howard Gardner identified individual talents or aptitudes in his theory of multiple intelligences.[8] Based on the works of Carl Jung, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and Keirsey's Temperament Sorter focused on understanding how people's personality affects the way they interact personally, and how this affects the way individuals respond to each other within the learning environment[9].

Education can be physically divided into many different learning "modes" based on the senses, with the following four learning modalities being most important:[10]

- Kinesthetic learning based on manipulating objects and engaging in activities.

- Visual learning based on observation and seeing what is being learned.

- Auditory learning based on listening to instructions/information.

- Tactile learning based on drawing or writing notes and hands-on activities.

Depending on their preferred learning modality, different teaching techniques have different levels of effectiveness. Effective teaching of all students requires a variety of teaching methods which cover all four learning modalities.

Educational psychology also takes into consideration elements of Developmental psychology as it greatly impacts an individual's cognitive, social and personality development:

- Cognitive Development - primarily concerned with the ways in which infants and children acquire and advance their cognitive abilities. Major topics in cognitive development are the study of language acquisition and the development of perceptual-motor skills.

- Social development - focuses on the nature and causes of human social behavior, with an emphasis on how people think about each other and how they relate to each other.

- Personality development - an individual's personality is a collection of emotional, thought, and behavioral patterns unique to a person that is consistent over time. Many personality theorists regard personality as a combination of various "traits," that determine how an individual responds to various situations.

These three elements of development continue throughout the entire educational process, but are viewed and approached differently at different ages and educational levels. During the first levels of education, playing games is used to foster social interaction and skills, basic language and mathematical skills are used to lay the foundation for cognitive skills, while arts and crafts are employed to develop creativity and personal thinking. Later on in the educational system, more emphasis is placed on the cognitive skills, learning more complex esoteric educational skills and lessons.

Sociology of education

The sociology of education is the study of how social institutions and forces affect educational processes and outcomes, and vice versa. By many, education is understood to be a means of overcoming handicaps, achieving greater equality and acquiring wealth and status for all. Learners may be motivated by aspirations for progress and betterment. The purpose of education can be to develop every individual to their full potential. However, according to some sociologists, a key problem is that the educational needs of individuals and marginalized groups may be at odds with existing social processes, such as maintaining social stability through the reproduction of inequality. The understanding of the goals and means of educational socialization processes differs according to the sociological paradigm used. The sociology of education is based in three differing theories of perspectives: Structural functionalists, conflict theory, and structure and agency.

Structural functionalism

Structural functionalists believe that society tends towards equilibrium and social order. They see society like a human body, where key institutions work like the body’s organs to keep the society/body healthy and well.[11] Social health means the same as social order, and is guaranteed when nearly everyone accepts the general moral values of their society. Hence structural functionalists believe the purpose of key institutions, such as education, is to socialize young members of society. Socialization is the process by which the new generation learns the knowledge, attitudes and values that they will need as productive citizens. Although this purpose is stated in the formal curriculum, it is mainly achieved through "the hidden curriculum,"[12] a subtler, but nonetheless powerful, indoctrination of the norms and values of the wider society. Students learn these values because their behavior at school is regulated until they gradually internalize them and so accept them.

Education must, however perform another function to keep society running smoothly. As various jobs in society become vacant, they must be filled with the appropriate people. Therefore the other purpose of education is to sort and rank individuals for placement in the labor market. Those with the greatest achievement will be trained for the most important jobs in society and in reward, be given the highest incomes. Those who achieve the least, will be given the least demanding jobs, and hence the least income.

Conflict Theory

The perspective of conflict theory, contrary to the structural functionalist perspective, believes that society is full of vying social groups who have different aspirations, different access to life chances and gain different social rewards.[13] Relations in society, in this view, are mainly based on exploitation, oppression, domination, and subordination. This is a considerably more cynical picture of society than the previous idea that most people accept continuing inequality. Some conflict theorists believe education is controlled by the state which is controlled by those with the power, and its purpose is to reproduce the inequalities already existing in society as well as legitimize ‘acceptable’ ideas which actually work to reinforce the privileged positions of the dominant group. [13] Connell and White state that the education system is as much an arbiter of social privilege as a transmitter of knowledge.[14]

Education achieves its purpose by maintaining the status quo, where lower class children become lower class adults, and middle and upper class children become middle and upper class adults. This cycle occurs because the dominant group has, over time, closely aligned education with middle class values and aspirations, thus alienating people of other classes.[14] Many teachers assume that students will have particular middle class experiences at home, and for some children this assumption isn’t necessarily true. Some children are expected to help their parents after school and carry considerable domestic responsibilities in their often single-parent home.[15] The demands of this domestic labor often make it difficult for them to find time to do all their homework and thus affects their performance at school.

Structure and Agency

This theory of social reproduction has been significantly theorized by Pierre Bourdieu. However Bourdieu as a social theorist has always been concerned with the dichotomy between the objective and subjective, or to put it another way, between structure and agency. Bourdieu has therefore built his theoretical framework around the important concepts of habitus, field and cultural capital. These concepts are based on the idea that objective structures determine the probability of individuals' life chances, through the mechanism of the habitus, where individuals internalize these structures. However, the habitus is also formed by, for example, an individual's position in various fields, their family and their everyday experiences. Therefore one's class position does not determine one's life chances although it does play an important part alongside other factors.

Bourdieu employed the concept of cultural capital to explore the differences in outcomes for students from different classes in the French educational system. He explored the tension between the conservative reproduction and the innovative production of knowledge and experience.[16] He found that this tension is intensified by considerations of which particular cultural past and present is to be conserved and reproduced in schools. Bourdieu argues that it is the culture of the dominant groups, and therefore their cultural capital, which is embodied in schools, and that this leads to social reproduction.[16]

The cultural capital of the dominant group, in the form of practices and relation to culture, is assumed by the school to be the natural and only proper type of cultural capital and is therefore legitimated. It thus demands “uniformly of all its students that they should have what it does not give.”[17]. This legitimate cultural capital allows students who possess it to gain educational capital in the form of qualifications. Those students of less privileged classes are therefore disadvantaged. To gain qualifications they must acquire legitimate cultural capital, by exchanging their own (usually working-class) cultural capital.[18] This process of exchange is not a straight forward one, due to the class ethos of the less privileged students. Class ethos is described as the particular dispositions towards, and subjective expectations of, school and culture. It is in part determined by the objective chances of that class.[19] This means, that not only is it harder for children to succeed in school due to the fact that they must learn a new way of ‘being’, or relating to the world, and especially, a new way of relating to and using language, but they must also act against their instincts and expectations. The subjective expectations influenced by the objective structures located in the school, perpetuate social reproduction by encouraging less-privileged students to eliminate themselves from the system, so that fewer and fewer are to be found as one progresses through the levels of the system. The process of social reproduction is neither perfect nor complete,[16] but still, only a small number of less-privileged students make it all the way to the top. For the majority of these students who do succeed at school, they have had to internalize the values of the dominant classes and take them as their own, to the detriment of their original habitus and cultural values.

Therefore Bourdieu's perspective reveals how objective structures play a large role in determining the achievement of individuals at school, but allows for the exercise of an individual's agency to overcome these obstacles, although this choice is not without its penalties.

Challenges in Education

The goal of education is fourfold: the social purpose, intellectual purpose, economic purpose, and political/civic purpose. Current education issues include which teaching method(s) are most effective, how to determine what knowledge should be taught, which knowledge is most relevant, and how well the pupil will retain incoming knowledge.

There are a number of highly controversial issues in education. Should some knowledge be forgotten? Should classes be segregated by gender? What should be taught? There are also some philosophies, for example Transcendentalism, that would probably reject conventional education in the belief that knowledge should be gained through more direct personal experience.

Educational progressives or advocates of unschooling often believe that grades do not necessarily reveal the strengths and weaknesses of a student, and that there is an unfortunate lack of youth voice in the educational process. Some feel the current grading system lowers students' self-confidence, as students may receive poor marks due to factors outside their control. Such factors include poverty, child abuse, and prejudiced or incompetent teachers.

By contrast, many advocates of a more traditional or "back to basics" approach believe that the direction of reform needs to be the opposite. Students are not inspired or challenged to achieve success because of the dumbing down of the curriculum and the replacement of the "canon" with inferior material. They believe that self-confidence arises not from removing hurdles such as grading, but by making them fair and encouraging students to gain pride from knowing they can jump over these hurdles. On the one hand, Albert Einstein, the most famous physicist of the twentieth century, who is credited with helping us understand the universe better, was not a model school student. He was uninterested in what was being taught, and he did not attend classes all the time. On the other hand, his gifts eventually shone through and added to the sum of human knowledge.

Education has always been and will most likely continue to be a contentious issue across the world. Like many complex issues, it is doubtful that there is one definitive answer. Rather, a mosaic approach that takes into consideration the national and regional culture the school is located in as well as remaining focused on what is best for the children being instructed, as is done in some areas, will remain the best path for educators and officials alike.

Developing countries

In developing countries, the number and seriousness of the problems faced are naturally greater. People are sometimes unaware of the importance of education, and there is economic pressure from those parents who prioritize their children's making money in the short term over any long-term benefits of education. Recent studies on child labor and poverty have suggested that when poor families reach a certain economic threshold where families are able to provide for their basic needs, parents return their children to school. This has been found to be true, once the threshold has been breached, even if the potential economic value of the children's work has increased since their return to school. Teachers are often paid less than other similar professions.

India is developing technologies that skip land based phone and internet lines. Instead, India launched EDUSAT, an education satellite that can reach more of the country at a greatly reduced cost. There is also an initiative to develop cheap laptop computers to be sold at cost, which will enable developing countries to give their children a digital education, and to close the digital divide across the world.

In Africa, NEPAD has launched an "e-school programme" to provide all 600,000 primary and high schools with computer equipment, learning materials and internet access within 10 years. Private groups, like the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, are working to give more individuals opportunities to receive education in developing countries through such programs as the Perpetual Education Fund.

Internationalization

Education is becoming increasingly international. Not only are the materials becoming more influenced by the rich international environment, but exchanges among students at all levels are also playing an increasingly important role. In Europe, for example, the Socrates-Erasmus Program stimulates exchanges across European universities. Also, the Soros Foundation provides many opportunities for students from central Asia and eastern Europe. Some scholars argue that, regardless of whether one system is considered better or worse than another, experiencing a different way of education can often be considered to be the most important, enriching element of an international learning experience.[20]

Notes

- ↑ educate The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ Jane Healy, Your Child's Growing Mind: Brain Development and Learning From Birth to Adolescence (Broadway 2004, ISBN 0767916158).

- ↑ Carol Garhart Mooney, Theories of Childhood: An Introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget & Vygotsky (Redleaf Press, 2000, ISBN 188483485X).

- ↑ "Ethiopia: Higher and Vocational Education since 1975" Encyclopedia of the Nations, 1991. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ Daniel Taghioff, Seeds of Consensus—The Potential Role for Information and Communication Technologies in Development.Seminar in Advanced Methodologies and Professional Practice, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, April 2001. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ J. D. Finn, S. B. Gerber, and J. Boyd-Zaharias, "Small classes in the early grades, academic achievement, and graduating from high school," Journal of Educational Psychology, 97, (2005):214-233.

- ↑ Rita Stafford Dunn and Kenneth J. Dunn, Teaching Students Through Their Individual Learning Styles: A Practical Approach (Prentice Hall College Div, 1978, ISBN 0879098082).

- ↑ Howard Gardner, Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice (New York: Basic Books, 2006, ISBN 0465047688).

- ↑ Naomi L. Quenk, Essentials of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Assessment (Essentials of Psychological Assessment) (Wiley, 1999, ISBN 0471332399).

- ↑ Madison Michell, Kinesthetic, Visual, Auditory, Tactile, Oh My! What Are Learning Modalities and How Can You Incorporate Them in the Classroom? Edmentum, September 25, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ J. Bessant and R. Watts, Sociology Australia (Allen & Unwin, 2002, ISBN 1865086126).

- ↑ G. Harper, “Society, culture, socialization and the individual” in C. Stafford and B. Furze, (eds). Society and Change, (Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia, 1997)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 B. Furze and P. Healy, “Understanding society and change” in C. Stafford and B. Furze. (eds.) Society and Change, (Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia, 1997).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 R. W. Connell and V. White, "Child poverty and educational action" in D. Edgar, D. Keane, and P. McDonald (eds), Child Poverty (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1989).

- ↑ B. Wilson and J. Wyn, Shaping Futures: Youth Action for Livelihood (Allen & Unwin, 1987, ISBN 004302002X).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 R. Harker, “Education and Cultural Capital” in R. Harker, C. Mahar, and C. Wilkes, (eds). An Introduction to the Work of Pierre Bourdieu: the Practice of Theory (Macmillan Press, 1990, ISBN 0312049323).

- ↑ D. Swartz, “Pierre Bourdieu: The Cultural Transmission of Social Inequality,” in D. Robbins. Pierre Bourdieu Volume II. (London: Sage Publications, 2000), 207-217.

- ↑ R. Harker, “On Reproduction, Habitus and Education” in D. Robbins, (1984), 164-176.

- ↑ K. Gorder, “Understanding School Knowledge: a critical appraisal of Basil Bernstein and Pierre Bourdieu” in D. Robbins, (1980), 218-233.

- ↑ H.F.W. Dubois, G. Padovano, & G. Stew, "Improving international nurse training: an American–Italian case study." International Nursing Review 53(2) (2006): 110–116.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benei, Veronique. Manufacturing Citizenship: Education and Nationalism in Europe, South Asian and China. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0415364881

- Bessant, J. and R. Watts. Sociology Australia. Allen & Unwin, 2002. ISBN 1865086126

- Bifulco, Robert and Helen Ladd, "Institutional Change and Coproduction of Public Services: The Effect of Charter Schools on Parental Involvement." Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory (Oct 2006): 552-576.

- Bourdieu, Pierre and Jean Claude Passeron. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Sage Publications, 1990. ISBN 978-0803983205

- Buddin, Richard and Ron Zimmer, "Student achievement in charter schools:A complex picture." Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (2005): 351-371.

- Dharampal. The Beautiful Tree: Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth Century. Other India Press, 2000 (original 1983).

- Dubois, H.F.W., G. Padovano, & G. Stew. Improving international nurse training: an American–Italian case study. International Nursing Review 53(2) (2006): 110–116.

- Dunn, Rita Stafford, and Kenneth J. Dunn. Teaching Students Through Their Individual Learning Styles: A Practical Approach. Prentice Hall College Div, 1978. ISBN 0879098082

- Edgar, D., D. Keane, and P. McDonald (eds). Child Poverty. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1989.

- Finn, J.D., S. B. Gerber, and J. Boyd-Zaharias, "Small classes in the early grades, academic achievement, and graduating from high school," Journal of Educational Psychology 97 (2005): 214-233.

- Gardner, Howard. Multiple Intelligences: New Horizons in Theory and Practice. New York: Basic Books, 2006. ISBN 0465047688

- Gollnick, Donna M. and Philip C. Chinn. Multicultural Education in a Pluralistic Society & Exploring Diversity Package. Prentice Hall, 2005. ISBN 978-0131555181

- Harker, Richard, Cheleen Mahar, and Chris Wilkes. An Introduction to the Work of Pierre Bourdieu: The Practice of Theory. Palgrave Macmillan, 1990. ISBN 0333524764

- Healy, Jane. Your Child's Growing Mind: Brain Development and Learning From Birth to Adolescence, third ed., Broadway, 2004. ISBN 0767916158

- Li Yi. The Structure and Evolution of Chinese Social Stratification. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005. ISBN 0761833315

- Lucas, J. L., M. A. Blazek, & A. B. Raley. "The lack of representation of educational psychology and school psychology in introductory psychology textbooks." Educational Psychology 25 (2005): 347-351.

- Mooney, Carol Garhart. Theories of Childhood: An Introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget & Vygotsky. St. Paul, MN: Redleaf Press, 2000. ISBN 188483485X

- Quenk, Naomi L. Essentials of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Assessment (Essentials of Psychological Assessment). Wiley, 1999. ISBN 0471332399

- Sargent, M. The New Sociology for Australians, Third Ed. Melbourne: Longman Chesire, 1994.

- Schofield, K. “The Purposes of Education.” Queensland State Education, 2010 (original 1999).

- Shih, Timothy, K. Shih and Jason C. Hung, Eds. Future Directions in Distance Learning and Communication Technologies. IGI Global, 2006. ISBN 978-1599043760

- Siljander, Pauli. Systemaattinen johdatus kasvatustieteeseen. Otava, 2002.

- Stafford, C., and Furze, B. (eds.). Society and Change. Melbourne: Macmillan Education Australia.

- Wilson, B., and J. Wyn. Shaping Futures: Youth Action for Livelihood. Allen & Unwin, 1987. ISBN 004302002X

External links

All links retrieved July 12, 2019.

- Lys Anzia, "Educate a Woman, You Educate a Nation" - South Africa Aims to Improve its Education for Girls WNN - Women News Network, August 28, 2007.

- World Bank Education

- UNESCO - International Institute for Educational Planning

- The Encyclopedia of Informal Education

| General subfields of the Social Sciences |

|---|

| Anthropology | Communication | Economics | Education |

| Linguistics | Law | Psychology | Social work | Sociology |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 20:41:46 | 182 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Education | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF