Battle Of Gettysburg

From Nwe

From Nwe

| Battle of Gettysburg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

The battle of Gettysburg, Pa. July 3d. 1863, by Currier and Ives |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| United States of America (Union) | Confederate States of America | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| George G. Meade | Robert E. Lee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 93,921 | 71,699 | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 23,055 (3,155 killed, 14,531 wounded, 5,369 captured/missing) | 22,231 (4,708 killed, 12,693 wounded, 5,830 captured/missing) | ||||||

The Battle of Gettysburg (July 1 – July 3 1863), fought in the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, was the bloodiest[1] battle of the American Civil War is cited as the war's turning point.[2] Union Major General George G. Meade's Army of the Potomac defeated attacks by Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, ending Lee's invasion of the North.

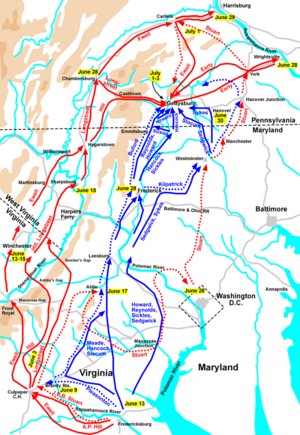

In May 1863, Lee led his Army of Northern Virginia through the Shenandoah Valley, hoping to reach as far as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, or Philadelphia, to influence Northern politicians to give up their prosecution of the war. Union Maj. General Meade of the Army of the Potomac pursued Lee, and the two armies met at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863. The northwest of town were defended by a Union cavalry division, reinforced with two corps of Union infantry. Two Confederate corps assaulted them from the northwest and from the north, collapsing hastily developed Union lines and sending the defenders retreating through streets of the town towards the south.

On the second day of battle, both armies re-assembled. The Union line was laid out resembling a fishhook. Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union's left flank, fierce fighting raged at Little Round Top, Wheatfield, Devil's Den, and Peach Orchard. On the Union right, the fighting escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp's Hill and on Cemetery Hill. Union defenders held their lines.

On the third day of battle, July 3, fighting resumed on Culp's Hill, cavalry battles raged in the east and south but the main event was an infantry assault by 12,500 Confederates against the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. Pickett's Charge (see below) was repulsed by Union rifle and artillery fire at great losses to the Confederate army. Lee led his army on a retreat back to Virginia. Between 46,000 and 51,000 Americans were casualties in the three-day battle.

For the Union, the victory at Gettysburg was electrifying. The mystique of Robert E. Lee's invincibility was broken, strengthening the political will to prosecute the war to the end. The Confederates lost politically as well as militarily. The defeat doomed attempts to gain European recognition and support for their cause, and led at least some of their politicians to think about suing for peace.

In November, President Lincoln used the dedication ceremony for the Gettysburg National Cemetery to honor the Union dead and to redefine the purpose of the war in his historic Gettysburg Address.

First Day of Battle

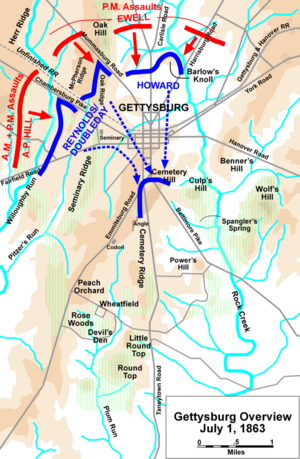

General Buford realized the importance of high ground, knowing that if the Confederates could gain control of the heights, Meade's army would have a hard time. He decided to utilize three ridges west of Gettysburg. Confronted by a larger force, occupying this territory would help him to buy time until the arrival of Union infantrymen reinforcements who could then assume strong defensive positions south of the town, that is, Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Culp's Hill.[3]

Heth's division advanced, commanded by Brig. Gens. James J. Archer and Joseph R. Davis, proceeding easterly. Three miles west of town, 7:30 A.M. July 1, Heth's two brigades met light resistance from cavalry. They encountered dismounted troopers from Col. William Gamble's cavalry brigade, raised resistance and employed delaying tactics from behind fence posts firing their breechloading carbines.[4] By 10:20 A.M., The Confederates had pushed Union cavalrymen east to McPherson Ridge, when a vanguard of I Corps under Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds arrived.[5]

While General Reynolds was directing troop and artillery placements just east of the woods, he fell from his horse, killed instantly by a bullet striking him behind left ear. Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday assumed command. Fighting in Chambersburg Pike area lasted until 12:30 P.M. It resumed when Heth's entire division engaged, adding the brigades of Pettigrew and Col. John M. Brockenbrough.[6]

When Pettigrew's North Carolina Brigade came on line they flanked the 19th Indiana and drove the Iron Brigade back. 26th North Carolina lost heavily, leaving the field on the first day of battle with 212 men. By end of the three-day battle, they would have 152 men and the highest casualty percentage for one battle of any other regiment, north or south.[7] The Iron Brigade was pushed out of the woods toward Seminary Ridge. Hill added Maj. Gen. William Dorsey Pender's division to the assault and I Corps was driven back through the grounds of the Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg.[8]

Two divisions of Ewell's Second Corps, marching west toward Cashtown in accordance with Lee's order for the army to concentrate in that vicinity, turned south on Carlisle and Harrisburg Roads toward Gettysburg, while Union XI Corps (Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard) raced north on Baltimore Pike and Taneytown Road. By early afternoon, the Federal line ran in a semi-circle west, north, and northeast of Gettysburg.[9]

The Federals did not have enough troops; Cutler, who was deployed north of Chambersburg Pike, had his right flank exposed. A division of the XI Corps was unable to deploy in time to strengthen the line, so Doubleday was forced to deploy reserve brigades to salvage his line.[10]

2:00 P.M., the Second Corps divisions of Maj. Gens. Robert E. Rodes and Jubal Early assaulted and out-flanked the Union I and XI Corps positions north and northwest of town. The brigades of Col. Edward A. O'Neal and Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson suffered severe losses attacking the I Corps division of Brig. Gen. John C. Robinson south of Oak Hill. Early's division profited from a blunder made by Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow, when he advanced his XI Corps division to Blocher's Knoll (directly north of town and now known as Barlow's Knoll).[11] This position was a weak one, susceptible to attack from multiple sides, and Early's troops soon overran his division, which constituted the right flank of the Union Army's position. Barlow was wounded and captured in the attack.[12]

Federal positions collapsed both north and west of town and Gen. Howard ordered a retreat to the high ground on the southern side of the town, Cemetery Hill, where Brig. Gen. Adolph von Steinwehr's division was waiting in reserve.[13]

Gen. Lee understood the defensive potential to the Union if they could hold this high ground. He sent orders to Ewell that Cemetery Hill be taken "if practicable." Ewell chose not to attempt the assault.[14]

The first day at Gettysburg was more significant than simply a prelude to the bloody second and third days but rather ranks as the 23rd biggest battle of the war by the number of troops engaged, that is, one quarter of Meade's army (22,000 men) and one third of Lee's army (27,000).[15]

Second Day of Battle

Plans and movement

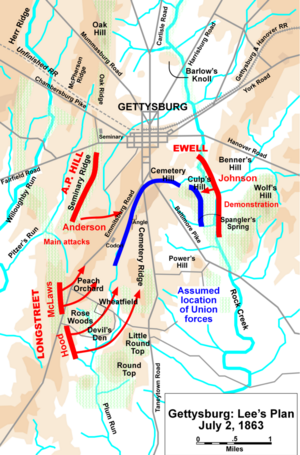

On July 1st and 2nd the remaining infantry of both armies arrived, including the Union II, III, V, VI, and XII Corps. Longstreet's third division, commanded by George Pickett, had begun its march from Chambersburg and would not arrive until late on July 2.[16]

The Union line ran from Culp's Hill, to Cemetery Hill just south of town, then south for two miles along Cemetery Ridge, terminating just north of Little Round Top. Most of the XII Corps was on Culp's Hill, while the remnants of I and XI Corps defended Cemetery Hill. II Corps covered most of the northern half of Cemetery Ridge, and III Corps was ordered to take up position to its flank. The Union line was a "fishhook" formation. The Confederate line paralleled the Union line about a mile to the west on Seminary Ridge, ran east through town, then curved southeast to a point opposite Culp's Hill. The Federal army had interior lines, while the Confederate line was nearly five miles in length.[17]

Lee's battle plan on July 2 called for Longstreet's First Corps to position itself to attack the Union's left flank, facing northeast astraddle the Emmitsburg Road, and to roll up Federal line. The attack sequence was to begin with Maj. Gens. John Bell Hood's and Lafayette McLaws's divisions, followed by Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson's division of Hill's Third Corps. The en echelon sequence of this attack would prevent Meade from shifting troops from the center to bolster his left. Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's and Jubal Early's Second Corps divisions were to make a "demonstration" against Culp's and Cemetery Hills, then to turn the demonstration into a full-scale attack if the opportunity presented itself[18].

Lee's plan, based on faulty intelligence, was exacerbated by Stuart's continued absence from the battlefield. Instead of moving beyond the Federals' left and attacking their flank, Longstreet's left division, under McLaws, would face Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles's III Corps directly in their path. Sickles, dissatisfied with the position assigned him at the southern end of Cemetery Ridge saw higher ground as more favorable to artillery positions a half mile to the west. He advanced his corps, without orders&mdash, to higher ground along the Emmitsburg Road. Thus, the new line ran from Devil's Den, northwest to Sherfy farm's Peach Orchard, northeast along Emmitsburg Road to south of Codori farm. This created an untenable position at Peach Orchard; Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys's division (in position along the Emmitsburg Road) and Maj. Gen. David B. Birney's division, were subject to attacks from two sides, spread out over longer front than their small corps could defend effectively.[19]

Longstreet's attack was to be made as early as practicable; Longstreet was given permission by Lee to wait for the arrival of one of his brigades, and, while marching to the assigned position, his men came within sight of the Union signal station on Little Round Top. Countermarching to avoid detection wasted time, so Hood's and McLaws's divisions did not launch their attacks until 4 P.M. and 5 P.M., respectively.[20]

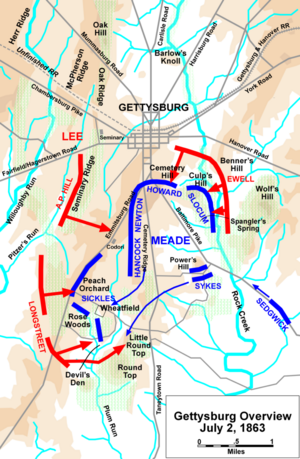

Attacks on Union left flank

Longstreet's divisions slammed into Union III Corps. Meade had sent 20,000 reinforcements[21] - the entire V Corps, Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell's division of II Corps, XII Corps, and small portions of newly arrived VI Corps. The Confederate assault deviated from Lee's plan; Hood's division moved easterly, losing alignment with the Emmitsburg Road,[22] and attacking Devil's Den and Little Round Top. McLaws, advancing on Hood's left, drove multiple attacks into III Corps and Wheatfield overwhelmed them in Peach Orchard. McLaws's attack reached Plum Run Valley (the "Valley of Death") before being beaten back by the Pennsylvania Reserves' division of V Corps, moving down from Little Round Top. The III Corps was destroyed as a combat unit in this battle and Sickles's leg was amputated after it was shattered by a cannonball. Caldwell's division was destroyed piecemeal in Wheatfield. Anderson's division assault on McLaws's left, starting around 6 P.M., reached the crest of Cemetery Ridge, they could not hold the position in face of counterattacks from the II Corps.[23]

As fighting raged in the Wheatfield and Devil's Den, Col. Strong Vincent of V Corps held onto Little Round Top, an important hill to the extreme left of the Union line. His brigade of four small regiments was able to resist repeated assaults by Brig. Gen. Evander Law's brigade of Hood's division. Meade's chief engineer, Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, had realized the importance of this position, and dispatched Vincent's brigade, an artillery battery, and the 140th New York to occupy Little Round Top mere minutes before Hood's troops arrived. The defense of Little Round Top with a bayonet charge by the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment was one of the most fabled episodes in the Civil War and propelled Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain into prominence after the war.[24]

Attacks on Union right flank

7:00 P.M., the Second Corps' attack by Johnson's division on Culp's Hill started late. Union XII Corps had been sent to defend against Longstreet's attacks. The only portion of corps remaining on the hill was a brigade of New Yorkers under Brig. Gen. George S. Greene. Greene's men held off the Confederate attackers although the Southerners did capture a portion of an abandoned Federal works.[25]

Early's brigades attacked the Union XI Corps positions on East Cemetery Hill where Col. Andrew L. Harris 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, came under attack, losing half his men. Early failed to support his brigades, and Ewell's remaining division, Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes, failed to aid Early's attack by moving against Cemetery Hill. The Union army's interior lines enabled commanders to shift troops to critical areas, and with reinforcements from II Corps, Federal troops retained possession of Cemetery Hill and Early's brigades were forced to withdraw.[26]

Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton III's brigade fought a minor engagement with George Armstrong Custer's Michigan cavalry near Hunterstown northeast of Gettysburg.[27]

Third Day of Battle

General Lee renewed his attack, Friday, July 3, using the same basic plan: Longstreet would attack the Federal left flank while Ewell attacked Culp's Hill.[28] Longstreet was not ready and Union XII Corps troops started a dawn artillery bombardment against the Confederates on Culp's Hill. The Confederates attacked, and the second fight for Culp's Hill ended at 11 A.M., after seven hours of bitter combat.[29]

Lee was forced to change plans. Longstreet would command Pickett's Virginia division, six brigades from Hill's Corps in an attack on Federal II Corps position at the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. All the artillery that the Confederacy could bring to bear on Federal positions bombarded and weakened the enemy's line.[30]

1:00 P.M., 159 Confederate guns[31] began an artillery bombardment that was the largest of the war. To save valuable ammunition for the infantry attack, the Army of the Potomac's artillery did not return the enemy's fire. After waiting 15 minutes, 80 Federal cannon added to the barrage. At 3:00 P.M., the cannon fire subsided and 12,500 Southern soldiers stepped from the ridgeline to advance three-quarters of a mile to Cemetery Ridge, known to history as "Pickett's Charge." There was fierce flanking artillery fire from Union positions on Cemetery Hill north of Little Round Top and musket canister fire from the II Corps as the Confederates approached. The Federal line wavered, broke temporarily before reinforcements rushed into the breach and the Confederate attack was repulsed.[32]

On July 3, Stuart was sent to guard the Confederate left flank and prepared to exploit any success that the infantry might achieve on Cemetery Hill, flanking the Federal right and hitting trains and lines of communications. Three miles east of Gettysburg, at what is now called "East Cavalry Field," Stuart's forces collided with Federal cavalry: Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg's division and George A. Custer's brigade. A Lengthy mounted battle including hand-to-hand sabre combat, ensued. Custer's charge, leading 1st Michigan Cavalry, blunted the attack by Wade Hampton's brigade, blocking Stuart from achieving his objectives in the Federal rear. WhenPickett's Charge ended, Meade ordered Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick to launch a cavalry attack against infantry positions of Longstreet's Corps of Big Round Top. Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth protested against the futility of such a move but obeyed orders. Farnsworth was killed in the attack and his brigade suffered significant losses.[33]

Aftermath

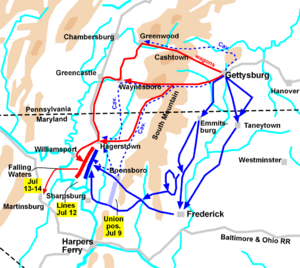

July 4, the same day that the Vicksburg garrison surrendered to Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, Lee reformed his lines into a defensive position, hoping that Meade would attack. Meade ordered a series of small probing actions, sending U.S. Regulars towards the Confederate lines. Under artillery fire, Meade decided not to press attack the attack and withdrew. By mid-afternoon, the firing had stopped and both armies began collecting their remaining wounded and to bury the dead. A proposal by Lee for prisoner exchange was rejected by Meade.[34]

July 5, in driving rain, the bulk of the Army of Northern Virginia left. The Battle of Gettysburg over; the Confederates headed back to Virginia. Meade's army followed. The recently rain-swollen Potomac river trapped Lee's army on the north bank. By the time the Federals caught up, the Confederates had crossed into Virginia. Rear-guard action at Falling Waters on July 14 ended the Gettysburg Campaign, adding more names to the casualty lists, including General Pettigrew.[35]

General Lee had entertained the belief that his men were invincible; Lee's experiences with the army, including the great victory at Chancellorsville in early May, and the rout of Federals on July 1, had convinced him of his own military genius.[36] Effects of this blind faith and the fact that the Army of Northern Virginia had many new, inexperienced commanders, plus Lee's habit of giving generalized orders and leaving it up to his lieutenants to work out details all contributed to the defeat. After July 1, the Confederates were not able to coordinate attacks and Lee faced a new, very dangerous opponent in George Meade[37].

News of the Union victory electrified the North. A Headline in The Philadelphia Inquirer "VICTORY! WATERLOO ECLIPSED!" New York, George Templeton Strong wrote:[38]

The results of this victory are priceless. … The charm of Robert E. Lee's invincibility is broken. Army of the Potomac has at last found a general that can handle it, and has stood nobly up to its terrible work in spite of its long disheartening list of hard-fought failures. … Copperheads are palsied and dumb for the moment at least. … Government is strengthened four-fold at home and abroad.(George Templeton Strong, Diary, 330).

Confederates lost politically and militarily. During the final hours of battle, Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens approaching Union lines at Norfolk, Virginia, under a flag of truce. Instructions from Confederate President Jefferson Davis had limited powers on prisoner exchanges and other procedural matters. Historian James M. McPherson speculates that he had goals of presenting peace overtures. Davis hoped that Stephens would reach Washington from the south while Lee's victorious army was marching from the north. President Lincoln, upon hearing of the victory at Gettysburg, refused Stephens's request to pass through lines.

When the news reached London, lingering hopes of European recognition of the Confederacy were abandoned. Henry Adams wrote, "The disasters of the rebels are unredeemed by even any hope of success. It is now conceded that all idea of intervention is at an end."[39]

Casualties

Union casualties were 23,055 (3,155 killed, 14,531 wounded, 5,369 captured or missing).[40] Confederate casualties are difficult to estimate, perhaps 28,000 overall. Busey and Martin's definitive 2005 work, Regimental Strengths and Losses, documents 22,231 (4,708 killed, 12,693 wounded, 5,830 captured or missing).[41] The casualties for both sides during the entire campaign were 57,225.[42] One documented civilian death during the battle: Ginnie Wade, 20 years old, shot by a stray bullet that passed through her kitchen in town while she was making bread.[43]

7,000 soldiers had been killed outright; these bodies, lying in the hot summer sun, needed to be buried quickly. Over 3,000 horse carcasses[44] were burned in series of piles south of town; townsfolk became violently ill from the stench. Pennsylvania and New York state militia patrolled Gettysburg battlefield secured as much of the remaining military property. Ravages of war would still be evident in Gettysburg more than four months later when, on November 19, Soldiers' National Cemetery was dedicated. During this ceremony, President Abraham Lincoln with his Gettysburg Address would re-dedicate the nation to war effort and the ideal that no soldier at Gettysburg—North or South—had died in vain.

Today, Gettysburg National Cemetery and Gettysburg National Military Park are maintained by U.S. National Park Service as two of the nation's most revered historical landmarks.

Notes

- ↑ Gettysburg was the battle with the largest number of casualties. Antietam, the culmination of Lee's first invasion of the North, had the largest number of casualties in one day. Antietam had about 23,000 casualties in fighting. The second day of Gettysburg saw 20,000 casualties in fighting that lasted a few hours, from 4 p.m. until shortly after dark. The casualty rate at the peak of fighting on the second day in Wheatfield, Little Round Top, and Devil's Den are estimated to be faster than one casualty per second.

- ↑ James A. Rawley. Turning Points of the Civil War. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), 147 ; Richard A. Sauers, "Battle of Gettysburg," Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, David S. Heidler, and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., (NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 827; James M. McPherson. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. (Oxford University Press, 1988), 665; McPherson cites the combination of Gettysburg and Vicksburg as the turning point.

- ↑ Stephen W. Sears. Gettysburg. (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2003), 155.

- ↑ David G. Martin. Gettysburg July 1, rev. ed., (Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1996), 80-81. These breechloading carbines fired two or three times faster than muzzle-loaded carbine or rifle.

- ↑ Craig L. Symonds. American Heritage History of the Battle of Gettysburg. (HarperCollins, 2001), 71.

- ↑ Symonds, 74; Harry W. Pfanz. Gettysburg – The First Day. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 269-275.

- ↑ John W. Busey and David G. Martin. Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, 4th Ed., (Hightstown, NJ: Longstreet House, 2005), 298, 501.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, 275-293.

- ↑ Champ Clark and the Editors of Time-Life Books. (Gettysburg: The Confederate High Tide, Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985), 53.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, 158.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, 230.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, 156-238.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, 294.

- ↑ Pfanz, First Day, 344; Sears, 228; Noah Andre Trudeau. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. (NY: HarperCollins, 2002), 253. Both Sears and Trudeau record "if possible."

- ↑ Martin, 9, citing Thomas L. Livermore. Numbers & Losses in the Civil War in America. (Houghton Mifflin, 1900).

- ↑ Edwin B. Coddington. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. (NY: Scribner's, 1968), 333; Tucker, 327.

- ↑ Clark, 74; David J. Eicher. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 521.

- ↑ Sears, 255; Clark, 69

- ↑ Harry W. Pfanz. Gettysburg – The Second Day. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 93-97; Eicher, 523-524.

- ↑ Pfanz, Second Day, 119-23.

- ↑ Troy D. Harman. Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg. (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003), 59.

- ↑ Harman, 57.

- ↑ Sears, 833-835; Eicher, 530-535.

- ↑ Eicher, 527-530; Clark, 81-85.

- ↑ Harry W. Pfanz. Gettysburg: Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 205-234. Clark, 115-116.

- ↑ Pfanz, Culp's Hill, 235-283; Eicher, 538-539.

- ↑ Sears, 257; Edward G. Longacre. The Cavalry at Gettysburg. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 198-199.

- ↑ Harman, 63.

- ↑ Pfanz, Culp's Hill, 284-352; Eicher, 540-541

- ↑ Eicher, 542; Coddington, 485-486.

- ↑ Eicher, 543.

- ↑ McPherson, 661-663; Clark, 133-144; Symonds, 214-241

- ↑ Eicher, 549-550; Longacre, 226-231, 240-244; Jeffry D. Wert. Gettysburg: Day Three. (NY: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 272-280.

- ↑ Eicher, 550; Coddington, 539-544; Wert, 300.

- ↑ Clark, 147-157; Longacre, 268-269.

- ↑ Trudeau, 530.

- ↑ Tucker, 389-394.

- ↑ McPherson, 664.

- ↑ McPherson, 650, 664.

- ↑ Busey and Martin, 125.

- ↑ Busey and Martin, 260.

- ↑ Sears, 513.

- ↑ Sears, 391.

- ↑ Sears, 511.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Busey, John W., and David G. Martin. Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, 4th Ed., Hightstown, NJ: Longstreet House, 2005. ISBN 0944413676

- Clark, Champ, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. Gettysburg: The Confederate High Tide, Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. ISBN 0809447584

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. NY: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0684845695

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. NY: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0684849445

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War, A Narrative: Fredericksburg to Meridian. NY: Random House, 1958. ISBN 0394495179

- Harman, Troy D. Lee's Real Plan at Gettysburg. Mechanicsburg, PA : Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0811700542

- Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Gettysburg. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1986. ISBN 0803279418

- Martin, David G. Gettysburg July 1, rev. ed., Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 1996. ISBN 0938289810

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. (Oxford History of the United States) NY: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0195038630

- Nye, Wilbur S. Here Come the Rebels! Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, (original 1965) reprinted by Morningside House, 1984. ISBN 0890297800

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The First Day. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 0807826243

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg – The Second Day. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. ISBN 080781749X

- Pfanz, Harry W. Gettysburg: Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1993. ISBN 0807821187

- Rawley, James A. Turning Points of the Civil War. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1966. ISBN 0803289359

- Sauers, Richard A. "Battle of Gettysburg," Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, David S. Heidler, and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 039304758X

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2003, ISBN 0395867614.

- Symonds, Craig L. American Heritage History of the Battle of Gettysburg. HarperCollins, 2001. ISBN 006019474X

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. NY: HarperCollins, 2002. ISBN 0060193638

- Tucker, Glenn. High Tide at Gettysburg. (original 1958) reprinted by Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1983. ISBN 0914427822

- Wert, Jeffry D. Gettysburg: Day Three. NY: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0684859149

External links

All links retrieved January 12, 2022.

- Gettysburg National Military Park (National Park Service)

- Military History Online: The Battle of Gettysburg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 04:58:47 | 14 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Battle_of_Gettysburg | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF