Easter

From Nwe

From Nwe | Easter | |

|---|---|

|

|

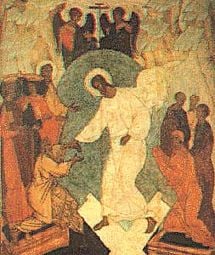

| Sixteenth-century Russian Orthodox icon of the Descent of Christ into Hades, the usual Orthodox icon for Pascha (Easter). | |

| Observed by | Most Christians. |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | Celebrates the resurrection of Jesus Christ. |

| Date | First Sunday after the first full moon on or after March 21 |

| Celebrations | church services, festive family meals, Easter egg hunts |

| Observances | Prayer, all-night vigil (Eastern Orthodox), sunrise service (especially American Protestant traditions) |

| Related to | Passover, Shrove Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Lent, Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, Pentecost and others. |

Easter, also called Pascha, commemorates the resurrection of Jesus, which Christians believe occurred on the third day after his crucifixion some time in the period between 27 to 33 C.E.. It is often considered by religious Christians to be their most important holiday, celebrating Christ's victory over death, in which they share through their belief in him. However, today, many families celebrate Easter in a completely secular way, as a non-religious holiday.

Easter also refers to the season of the church year, called Eastertide or the Easter Season. Traditionally, the Easter season lasted for the 40 days from Easter Day until Ascension Day, but now lasts for the 50 days until Pentecost. The first week of the Easter Season is known as Easter Week.

Easter is not a fixed holiday in relation to the civil calendar. It falls at some point between late March and late April each year (early April to early May in Eastern Christianity), following the cycle of the moon.

Easter is also linked to the Jewish Passover, especially for its position in the calendar. The Last Supper shared by Jesus and his disciples before his crucifixion was a Passover Seder, as described in the synoptic gospels. The Gospel of John, however, places Christ's death at the time of the slaughter of the Passover lambs, which would put the Last Supper before Passover.

Etymology

The English name, "Easter" is thought to derive from the name of a Anglo-Saxon goddess of the dawn called Eostre or Ēastre in various dialects of Old English and Ostara in German. In England, the annual festive time in her honor was in the "Month of Easter," equivalent to April/Aprilis. In his De temporum ratione the The Venerable Bede, an eighth-Century English Christian monk wrote: "Eostur-month, which is now interpreted as the paschal month, was formerly named after the goddess Eostre, and has given its name to the festival." However, in recent years, some scholars have suggested that a lack of supporting documentation for this goddess might indicate that Bede assumed her existence based on the name of the month.

Jakob Grimm took up the question of Eostre in his Deutsche Mythologie of 1835, writing of various landmarks and customs which he believed to be related to a goddess Ostara in Germany. Critics suggest that Grimm took Bede's mention of a goddess Eostre at face value and constructed the parallel goddess Ostara around existing Germanic customs. Grimm also connected the Osterhase (Easter Bunny) and Easter Eggs to the goddess Ostara/Eostre and cited various place names in Germany as being evidence of Ostara, but critics observe these place names simply refer to either "east" or "dawn" rather than a goddess.

The giving of eggs at spring festivals was not restricted to Germanic peoples and could be found among the Persians, Romans, Jews, and the Armenians. They were a widespread symbol of rebirth and resurrection and thus might have been adopted from any number of sources.

In most languages, other than English, German, and some Slavic languages, the holiday's name is derived from the Greek name, Pascha which is itself derived from Pesach, the Hebrew festival of Passover.

History

The observance of any non-Jewish holiday by Christians is believed by some to be an innovation postdating the early church. It is likely that the early Christians—virtually all of whom were Jews—celebrated Passover in the normal Jewish way, but came to mark Easter as a special holiday as the Resurrection became increasingly central in Christian theology.

The ecclesiastical historian Socrates Scholasticus (b. 380) attributes the observance of Easter by the church to the perpetuation of local custom, stating that neither Jesus nor his Apostles enjoined the keeping of this or any other festival. Perhaps the earliest extant primary source referencing Easter is a second-century paschal homily by Melito of Sardis, which characterizes the celebration as a well-established one.[1]

Very early in the life of the church, it was accepted that the Lord's Supper was a practice of the disciples and an undisputed tradition. However, a dispute arose concerning the date on which Pascha (Easter) should be celebrated. This dispute came to be known as the Easter/Paschal controversy. Bishop Polycarp of Smyrna, by tradition a disciple of John the Evangelist, disputed the computation of the date with Bishop Anicetus of Rome, specifically as to when the pre-paschal fast should end.

The practice in Asia Minor at the time was that the fast ended on the fourteenth day of Nisan, strictly in accordance with the Hebrew calendar. The Roman practice was to continue the fast until the Sunday following. An objection to the fourteenth of Nisan was that it could fall on any day of the week. The Roman church wished to associate Easter with Sunday and sever the link to Jewish practices.

Shortly after Anicetus became bishop of Rome in about 155 C.E., Polycarp visited Rome, and among the topics discussed was this divergence of custom. Neither Polycarp nor Anicetus was able to persuade the other to his position, but neither did they consider the matter of sufficient importance to justify a schism, so they parted in peace leaving the question unsettled.

The debate did escalate, however; and a generation later, Bishop Victor of Rome excommunicated Bishop Polycrates of Ephesus and the rest of the bishops of Asia Minor for their adherence to the 14 Nisan custom. The excommunication was later rescinded, and the two sides reconciled upon the intervention of Bishop Irenaeus of Lyons, who reminded Victor of the tolerant precedent that had been established earlier.

By the third century, the Christian church in general had become Gentile-dominated and wished to further distinguish itself from Jewish practices. The rhetorical tone against 14 Nisan and any association of Easter with Passover became increasingly vehement. The tradition that Easter was to be celebrated "not with the Jews" meant that Pascha was not to be celebrated on 14 Nisan. The celebration of Pascha (Easter) on Sunday was formally settled at the First Council of Nicaea in 325, although by that time the Roman position had spread to most churches.

| Year | Western | Eastern |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | April 23 | April 30 |

| 2001 | April 15 | |

| 2002 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2003 | April 20 | April 27 |

| 2004 | April 11 | |

| 2005 | March 27 | May 1 |

| 2006 | April 16 | April 23 |

| 2007 | April 8 | |

| 2008 | March 23 | April 27 |

| 2009 | April 12 | April 19 |

| 2010 | April 4 | |

| 2011 | April 24 | |

| 2012 | April 8 | April 15 |

| 2013 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2014 | April 20 | |

| 2015 | April 5 | April 12 |

| 2016 | March 27 | May 1 |

| 2017 | April 16 | |

| 2018 | April 1 | April 8 |

| 2019 | April 21 | April 28 |

| 2020 | April 12 | April 19 |

According to Eusebius, (Life of Constantine, Book III chapter 18[13]), Emperor Constantine I declared: "Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Savior a different way." However, the custom of Christians and Jews joining in the Passover feast seems to have persisted, as Saint John Chrysostom found it necessary to condemn such inter-faith activities in his sermons. "The very idea of going from a church to a synagogue is blasphemous," he declared, and "to attend the Jewish Passover is to insult Christ."[2]

Date of Easter

Easter and the holidays that are related to it are moveable feasts, in that they do not fall on a fixed date in the Gregorian or Julian calendars (both of which follow the cycle of the sun and the seasons). Instead, the date for Easter is determined on a lunisolar calendar, as is the Jewish Calendar.

In Western Christianity, based on the Gregorian calendar, Easter falls on a Sunday from March 22 to April 25 inclusive. In the Julian calendar used by Eastern Christianity, Easter also falls on a Sunday from "March 22 to April 25" but—due to the 13-day difference between the present calendars—these dates are reckoned as April 4 to May 8.

The First Council of Nicaea decided that all Christians would celebrate Easter on the same day, which would be a Sunday. The council did not, however, declare conclusively whether the Alexandrian or Roman calculations of the date would be normative. It took a while for the Alexandrian rules to be adopted throughout Christian Europe. The Church of Rome continued to use its own methods until the sixth century, when it may have adopted the Alexandrian method. Churches in western continental Europe used a late Roman method until the late eighth century during the reign of Charlemagne, when they finally adopted the Alexandrian method. However, with the adoption of the Gregorian calendar by the Catholic Church in 1582 and the continuing use of the Julian calendar by Eastern Orthodox churches, the date on which Easter is celebrated again diverged.

Position in the church year

Western Christianity

In Western Christianity, Easter marks the end of the 40 days of Lent, a period of fasting and penitence in preparation for Easter which begins on Ash Wednesday.

The week before Easter is very special in the Christian tradition. The Sunday before Easter is Palm Sunday and the last three days before Easter are Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday (sometimes referred to as Silent Saturday). Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday and Good Friday respectively commemorate Jesus' entry into Jerusalem, the Last Supper and the Crucifixion. Holy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday are sometimes referred to as the Easter Triduum (Latin for "Three Days"). In some countries, Easter lasts two days, with the second called "Easter Monday." The week beginning with Easter Sunday is called Easter Week or the Octave of Easter. Many churches start celebrating Easter late in the evening of Holy Saturday at a service called the Easter Vigil.

Eastertide, the season of Easter, begins on Easter Sunday and lasts until the day of Pentecost, seven weeks later.

Eastern Christianity

In Eastern Christianity, preparations begin with Great Lent. Following the fifth Sunday of Great Lent is Palm Week, which ends with Lazarus Saturday. Lazarus Saturday officially brings Great Lent to a close, although the fast continues for the following week. After Lazarus Saturday comes Palm Sunday, Holy Week, and finally Easter itself, or Pascha (Πάσχα), and the fast is broken immediately after the divine liturgy. Easter is immediately followed by Bright Week, during which there is no fasting, even on Wednesday and Friday.

The Paschal Service consists of Paschal Matins, Hours, and Liturgy, which traditionally begins at midnight of Pascha morning. Placing the Paschal liturgy at midnight guarantees that no Divine liturgy will come earlier in the morning, ensuring its place as the pre-eminent "Feast of Feasts" in the liturgical year.

Religious observation of Easter

Western Christianity

The Easter festival is kept in many different ways among Western Christians. The traditional, liturgical observation of Easter, as practiced among Roman Catholics and some Lutherans and Anglicans, begins on the night of Holy Saturday with the Easter Vigil. This, the most important liturgy of the year, begins in total darkness with the blessing of the Easter fire, the lighting of the large Paschal candle (symbolic of the Risen Christ) and the chanting of the Exsultet or Easter Proclamation attributed to Saint Ambrose of Milan. After this service of light, a number of passages from the Old Testament are read. These tell the stories of creation, the sacrifice of Isaac, the crossing of the Red Sea, and the foretold coming of the Messiah. This part of the service climaxes with the singing of the Gloria and the Alleluia and the proclamation of the Gospel of the resurrection.

A sermon may be preached after the gospel. Then the focus moves from the lectern to the baptismal font. Easter was once considered the most perfect time to receive baptism, and this practice is still alive in Roman Catholicism. It is also being revived in some other circles. The Catholic sacrament of Confirmation is also celebrated at the Easter Vigil, which concludes with the celebration of the Eucharist (or 'Holy Communion').

Certain variations in the Easter Vigil exist: Some churches read the Old Testament lessons before the procession of the Paschal candle, and then read the gospel immediately after the Exsultet. Others keep this vigil very early on the Sunday morning instead of the Saturday night, particularly Protestant churches, to reflect the gospel account of the women coming to the tomb at dawn on the first day of the week. These services are known as the sunrise service and often occur in outdoor settings such as the church's yard or a nearby park. The first recorded sunrise service took place in 1732 among the Single Brethren in the MoravianCongregation at Herrnhut, Saxony, in what is now Germany.

In Polish culture, the Rezurekcja (Resurrection Procession) is the Easter morning Mass at daybreak when church bells ring out and explosions resound to commemorate Christ rising from the dead. Before the Mass begins at dawn, a festive procession with the Blessed Sacrament carried beneath a canopy encircles the church. As church bells ring out, hand bells are vigorously shaken by altar boys, the air is filled with incense and the faithful raise their voices heavenward in a triumphant rendering of age-old Easter hymns. After the eucharistic sacrament is carried around the church, the Easter Mass begins.

Additional celebrations are usually offered on Easter Sunday itself, when church attendance swells significantly, rivaled only by Christmas. Typically these services follow the usual order of Sunday services in a congregation, but also incorporate more festive elements. The music of the service, in particular, often displays a highly festive tone; the incorporation of brass instruments to supplement a congregation's usual instrumentation is common. Often a congregation's worship space is decorated with special banners and flowers (such as Easter lilies).

In predominantly Roman Catholic Philippines, the morning of Easter is marked with joyous celebration, the first being the dawn "Salubong," wherein large statues of Jesus and Mary are brought together to meet. This is followed by the joyous Easter Mass.

Eastern Christianity

Easter is the fundamental and most important festival of the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox. Every other religious festival on their calendars, including Christmas, is secondary in importance to the celebration of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. This is reflected in rich, Easter-connected customs in the cultures of countries that are traditionally of an Orthodox Christian majority. Eastern Catholics have similar emphasis in their calendars, and many of their liturgical customs are very similar.

Pascha (Easter) commemorates the primary act that fulfills the purpose of Christ's ministry on earth—to defeat death by dying and to purify and exalt humanity by voluntarily assuming and overcoming human frailty. This is succinctly summarized by the Paschal troparion, sung repeatedly during Pascha:

- Christ is risen from the dead,

- Trampling down death by death,

- And upon those in the tombs

- Bestowing life!

Celebration of the holiday begins with the preliminary rituals of Great Lent. In addition to fasting, almsgiving, and prayer, Orthodox Christians cut down on entertainment and non-essential activity, gradually eliminating them until Great and Holy Friday. Traditionally, on the evening of Great and Holy Saturday, the Midnight Office is celebrated shortly after 11:00 p.m.. At its completion all light in the church building is extinguished. A new flame is struck in the altar, or the priest lights his candle from a perpetual lamp kept burning there, and he then lights candles held by deacons or other assistants, who then go to light candles held by the congregation. Then the priest and congregation proceed around the church building, holding lit candles, re-entering ideally at the stroke of midnight, whereupon Matins begins immediately followed by the Paschal Hours and then the Divine Liturgy. Immediately after the Liturgy it is customary for the congregation to share a meal, essentially an agape dinner (albeit at 2:00 a.m. or later).

The day after, Easter Sunday proper, there is no liturgy, since the liturgy for that day has already been celebrated. Instead, in the afternoon, it is often traditional to hold "Agape vespers." In this service, it has become customary during the last few centuries for the priest and members of the congregation to read a portion of the Gospel of John (20:19–25 or 19–31) in as many languages as they can manage.

For the remainder of the week (known as "Bright Week"), all fasting is prohibited, and the customary greeting is "Christ is risen!"—to be responded with "Truly He is risen!"

Non-religious Easter traditions

As with many other Christian dates, the celebration of Easter extends beyond the church. Since its origins, it has been a time of celebration and feasting. Today it is commercially important, seeing wide sales of greeting cards and confectionery such as chocolate Easter eggs, marshmallow bunnies, Peeps, and jelly beans.

Despite the religious preeminence of Easter, in many traditionally Catholic or Protestant countries, Christmas is now a more prominent event in the calendar year, being unrivaled as a festive season, commercial opportunity, and time of family gathering—even for those of no or only nominal faith. Easter's relatively modest secular observances place it a distant second or third among the less religiously inclined where Christmas is so prominent.

Throughout North America, Australia, and parts of the UK, the Easter holiday has been partially secularized, so that some families participate only in the attendant revelry, central to which is decorating Easter eggs on Saturday evening and hunting for them Sunday morning, by which time they have been mysteriously hidden all over the house and garden.

In North America, eggs and other treats are delivered and hidden by the Easter Bunny in an Easter basket which children find waiting for them when they wake up. This traditionally apparently originated with Dutch settlers, inheriting the pre-Christian tradition of the Osterhase, or Ostara Hare. Many families in America will attend Sunday Mass or services in the morning and then participate in a feast or party in the afternoon.

In the UK children still paint colored eggs, but most British people simply exchange chocolate eggs on the Sunday. Chocolate Easter bunnies can be found in shops, but the idea is considered primarily a United States import. Many families have a traditional Sunday roast, particularly roast lamb, and eat foods like Simnel cake, a fruit cake with 11 marzipan balls representing the 11 faithful apostles. Hot cross buns, spiced buns with a cross on top, are traditionally associated with Good Friday, but today are eaten through Holy Week and the Easter period.

Notes

- ↑ Melito of Sardis. Homily on the Pascha, Kerux: The Journal of Northwest Theological Seminary at [1] www.kerux.com Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ↑ Saint John Chrysostom Eight Homilies Against the Jews in Medieval Sourcebook www.fordham.edu Retrieved December 17, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fritsch, Aaron. Easter. Mankata, Minn.: Creative Education, 2006. ISBN 978-1583413678

- Gulevich, Tanya. Encyclopedia of Easter, Carnival, and Lent. Detroit, Mich.: Omnigraphics, 2002. ISBN 978-0780804326

- Nerlove, Miriam. Easter. Niles, Ill.: A. Whitman, 1989. ISBN 978-0807518717

- Pienkowski, Jan. Easter: The King James Version. New York: Knopf, 1989. ISBN 978-0394824550

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:18:00 | 81 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Easter | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF