Victor Hugo

From Nwe

From Nwe

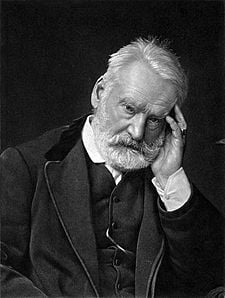

Victor-Marie Hugo, novelist, poet, playwright, dramatist, essayist and statesman, (February 26, 1802 – May 22, 1885) is recognized as one of the most influential Romantic writers of the nineteenth century. Born and raised in a royalist Catholic family, Hugo would—like so many of the Romantics—rebel against the conservative political and religious establishment in favor of liberal republicanism and the revolutionary cause. Hugo, like Gustave Flaubert, was disgusted with what he saw as the corruption of imperial France and with the Church's complicity in social injustices, and he devoted much of his energies (both in fiction and in essays) to overthrowing the monarchy.

While he made significant contributions to the revolutionary cause, Hugo was much more than a political activist. He was one of the most gifted writers of his times. Like Charles Dickens in England, Hugo became immensely popular among the working classes, viewed as a hero who exposed the underbelly of French society.

Hugo was recognized and continues to be lauded as a major force within the literary community. More than perhaps any other French author with the exception of François-René de Chateaubriand, Hugo ushered in the literary movement of Romanticism in France, which would become one of the most influential movements in the history of French and all European literature. Hugo espoused the virtues of Romanticism—liberty, individualism, spirit, and nature—which would become the tenets of high art for generations.

In his poetry, which in France is considered to be of equal worth to his frequently-translated novels, Hugo brought the lyrical style of German and English Romantic poets into the French language, in effect setting into motion a sea-change in the style of nineteenth-century French poetry. Among many volumes of poetry, Les Contemplations and La Légende des siècles stand particularly high in critical esteem. In the English-speaking world his best-known works are the novels Les Misérables and Notre-Dame de Paris (sometimes translated into English (to Hugo's dismay) as The Hunchback of Notre-Dame).

Hugo is a towering figure in French literature and politics, and in the Western movement of Romanticism.

Early life and influences

Victor Hugo was the youngest son of Joseph Léopold Sigisbert Hugo (1773–1828) and Sophie Trébuchet (1772-1821). He was born in 1802 in Besançon (in the region of Franche-Comté) and lived in France for the majority of his life. However, he was forced to go into exile during the reign of Napoleon III—he lived briefly in Brussels during 1851; in Jersey from 1852 to 1855; and in Guernsey from 1855 until his return to France in 1870.

Hugo's early childhood was turbulent. The century prior to his birth saw the overthrow of the Bourbon Dynasty in the French Revolution, the rise and fall of the First Republic, and the rise of the First French Empire and dictatorship under Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon was proclaimed Emperor two years after Hugo's birth, and the Bourbon Monarchy was restored before his eighteenth birthday. The opposing political and religious views of Hugo's parents reflected the forces that would battle for supremacy in France throughout his life: Hugo's father was a high-ranking officer in Napoleon's army, an atheist republican who considered Napoleon a hero; his mother was a staunch Catholic Royalist who is suspected of taking General Victor Lahorie as her lover, who was executed in 1812 for plotting against Napoleon.

Sophie followed her husband to posts in Italy where he served as a governor of a province near Naples, and Spain where he took charge of three Spanish provinces. Eventually weary of the constant moving required by military life, and at odds with her unfaithful husband, Sophie separated from Léopold in 1803 and settled in Paris. Thereafter she dominated Victor's education and upbringing. As a result, Hugo's early work in poetry and fiction reflect a passionate devotion to both the king and faith. It was only later, during the events leading up to France's 1848 Revolution, that he would begin to rebel against his Catholic Royalist education and instead champion Republicanism and free thought.

Early poetry and fiction

Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by François-René de Chateaubriand, the founder of Romanticism and France’s pre-eminent literary figure duing the early 1800s. In his youth, Hugo resolved to be “Chateaubriand or nothing," and his life would come to parallel that of his predecessor’s in many ways. Like Chateaubriand, Hugo would further the cause of Romanticism, become involved in politics as a champion of Republicanism, and be forced into exile due to his political stances.

The precocious passion and eloquence of Hugo's early work brought success and fame at an early age. His first collection of poetry Nouvelles Odes et Poesies Diverses was published in 1824, when Hugo was only 22 years old, and earned him a royal pension from Louis XVIII. Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, it was the collection that followed two years later in 1826 Odes et Ballades that revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song.

Against his mother's wishes, young Victor fell in love and became secretly engaged to his childhood sweetheart, Adèle Foucher (1803-1868). Unusually close to his mother, it was only after her death in 1821 that he felt free to marry Adèle the following year. He published his first novel the following year Han d'Islande (1823), and his second three years later Bug-Jargal (1826). Between 1829 and 1840 he would publish five more volumes of poetry; Les Orientales (1829), Les Feuilles d'automne (1831), Les Chants du crépuscule (1835), Les Voix intérieures (1837), and Les Rayons et les ombres (1840), cementing his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time.

Theatrical work

Hugo did not achieve such quick success with his works for the stage. In 1827, he published the never-staged verse drama Cromwell, which became more famous for the author's preface than its own worth. The play's unwieldy length was considered "unfit for acting." In his introduction to the work, Hugo urged his fellow artists to free themselves from the restrictions imposed by the French classical style of theater, and thus sparked a fierce debate between French Classicism and Romanticism that would rage for many years. Cromwell was followed in 1828 by the disastrous Amy Robsart, an experimental play from his youth based on the Walter Scott novel Kenilworth, which was produced under the name of his brother-in-law Paul Foucher and managed to survive only one performance before a less-than-appreciative audience.

The first play of Hugo's to be accepted for production under his own name was Marion de Lorme. Though initially banned by the censors for its unflattering portrayal of the French monarchy, it was eventually allowed to premiere uncensored in 1829, but without success. However, the play that Hugo produced the following year—Hernani—would prove to be one of the most successful and groundbreaking events of nineteenth century French theatre. On its opening night, the play became known as the "Battle of Hernani." Today the work is largely forgotten, except as the basis for the Giuseppe Verdi opera of the same name. However, at the time, performances of the work sparked near-riots between opposing camps of French letters and society: classicists versus romantics, liberals versus conformists, and republicans versus royalists. The play was largely condemned by the press, but played to full houses night after night, and all but crowned Hugo as the preeminent leader of French Romanticism. It also signaled that Hugo's concept of Romanticism was growing increasingly politicized. Romanticism, he expressed, would liberate the arts from the constraints of classicism just as liberalism would free the politics of his country from the tyranny of monarchy and dictatorship.

In 1832 Hugo followed the success of Hernani with Le roi s'amuse (The King Takes His Amusement). The play was promptly banned by the censors after only one performance, due to its overt mockery of the French nobility, but then went on to be very popular in printed form. Incensed by the ban, Hugo wrote his next play, Lucréce Borgia (see: Lucrezia Borgia), in only fourteen days. It subsequently appeared on the stage in 1833, to great success. Mademoiselle George the former mistress of Napoleon was cast in the main role, and an actress named Juliette Drouet played a subordinate part. However, Drouet would go on to play a major role in Hugo’s personal life, becoming his life-long mistress and muse. While Hugo had many romantic escapades throughout his life, Drouet was recognized even by his wife to have a unique relationship with the writer, and was treated almost as family. In Hugo’s next play (Marie Tudor, 1833), Drouet played Lady Jane Grey to George’s Queen Mary. However, she was not considered adequate to the role, and was replaced by another actress after opening night. It would be her last role on the French stage; thereafter she devoted her life to Hugo. Supported by a small pension, she became his unpaid secretary and travel companion for the next fifty years.

Hugo’s Angelo premiered in 1835, to great success. Soon afterward the Duke of New Orleans and brother of King Louis-Philippe, an admirer of Hugo’s work, founded a new theatre to support new plays. Théâtre de la Renaissance opened in November 1838 with the premiere of Ruy Blas. Though considered by many to be Hugo’s best drama, at the time it met with only average success. Hugo did not produce another play until 1843. The Burgraves played for only 33 nights, losing audiences to a competing drama, and it would be his last work written for the theater. Though he would later write the short verse drama Torquemada in 1869, it was not published until a few years before his death in 1882 and was never intended for the stage. However, Hugo's interest in the theater continued, and in 1864 he published a well-received essay on William Shakespeare, whose style he tried to emulate in his own dramas.

Mature fiction

Victor Hugo's first mature work of fiction appeared in 1829, and reflected the acute social conscience that would infuse his later work. Le Dernier jour d'un condamné (“Last Days of a Condemned Man”) would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Claude Gueux, a documentary short story that appeared in 1834 about a real-life murderer who had been executed in France, was considered by Hugo himself to be a precursor to his great work on social injustice, Les Miserables. But Hugo’s first full-length novel would be the enormously successful Notre-Dame de Paris (“The Hunchback of Notre Dame”), which was published in 1831 and quickly translated into other European languages. One of the effects of the novel was to shame the City of Paris to undertake a restoration of the much neglected Cathedral of Notre Dame, which was now attracting thousands of tourists who had read the popular novel. The book also inspired a renewed appreciation for pre-renaissance buildings, which thereafter began to be actively preserved.

Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but it would take a full 17 years for his greatest work, Les Miserables, to be realized and finally published in 1862. The author was acutely aware of the quality of the novel and publication of the work went to the highest bidder. The Belgian publishing house Lacroix and Verboeckhoven undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch. It also initially published only the first part of the novel ("Fantine"), which was launched simultaneously in major cities. Installments of the book sold out within hours, exerting an enormous impact on French society. Response ranged from wild enthusiasm to intense condemnation, but the issues highlighted in Les Miserables were soon on the agenda of the French National Assembly. Today the novel is considered a literary masterpiece, adapted for cinema, television and musical stage to an extent equaled by few other works of literature.

Hugo turned away from social/political issues in his next novel, Les Travailleurs de la Mer (“Toilers of the Sea”), published in 1866. Nonetheless, the book was well received, perhaps due to the previous success of Les Miserables. Dedicated to the channel island of Guernsey where he spent 15 years of exile, Hugo’s depiction of man’s battle with the sea and the horrible creatures lurking beneath its depths spawned an unusual fad in Paris, namely squid. From squid dishes and exhibitions, to squid hats and parties, Parisiennes became fascinated by these unusual sea creatures, which at the time were still considered by many to be mythical.

Hugo returned to political and social issues in his next novel, L'Homme Qui Rit (“The Man Who Laughs”), which was published in 1869 and painted a critical picture of the aristocracy. However, the novel was not as successful as his previous efforts, and Hugo himself began to comment on the growing distance between himself and literary contemporaries such as Gustave Flaubert and Emile Zola, whose naturalist novels were now exceeding the popularity of his own work. His last novel, Quatrevingt-treize (“Ninety-Three”), published in 1874, dealt with a subject that Hugo had previously avoided: the Reign of Terror that followed the French Revolution. Though Hugo’s popularity was on the decline at the time of its publication, many now consider Ninety-Three to be a powerful work on par with Hugo’s better-known novels.

Les Miserables

Les Misérables (trans. variously as “The Miserable Ones,” “The Wretched,” “The Poor Ones,” “The Victims”) is Hugo's masterpiece, ranking with Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace and Fyodor Dostoevsky's Brothers Karamazov as one of the most influential novels of the nineteenth century. It follows the lives and interactions of several French characters over a twenty year period in the early nineteenth century during the Napoleonic wars and subsequent decades. Principally focusing on the struggles of the protagonist—ex-convict Jean Valjean—to redeem himself through good works, the novel examines the impact of Valjean's actions as social commentary. It examines the nature of good, evil, and the law, in a sweeping story that expounds upon the history of France, architecture of Paris, politics, moral philosophy, law, justice, religion, and the types and nature of romantic and familial love.

Plot

Les Misérables contains a multitude of plots, but the thread that binds them together is the story of the ex-convict Jean Valjean, who becomes a force for good in the world, but cannot escape his past. The novel is divided into five parts, each part divided into books, and each book divided into chapters. The novel's more than twelve hundred pages in unabridged editions contains not only the story of Jean Valjean but many pages of Hugo's thoughts on religion, politics, and society, including his three lengthy digressions, including a discussion on enclosed religious orders, another on argot, and most famously, his epic retelling of the Battle of Waterloo.

After nineteen years of imprisonment for stealing bread for his starving family, the peasant Jean Valjean is released on parole. However, he is required to carry a yellow ticket, which marks him as a convict. Rejected by innkeepers who do not want to take in a convict, Valjean sleeps on the street. However, the benevolent Bishop Myriel takes him in and gives him shelter. In the night, he steals the bishop’s silverware and runs. He is caught, but the bishop rescues him by claiming that the silver was a gift. The bishop then tells him that in exchange, he must become an honest man.

Six years later, Valjean has become a wealthy factory owner and is elected mayor of his adopted town, having broken his parole and assumed the false name of Père Madeleine to avoid capture by Inspector Javert, who has been pursuing him. Fate, however, takes an unfortunate turn when another man is arrested, accused of being Valjean, and put on trial, forcing the real ex-convict to reveal his true identity. At the same time, his life takes another turn when he meets the dying Fantine, who had been fired from the factory and has resorted to prostitution. She has a young daughter, Cosette, who lives with an innkeeper and his wife. As Fantine dies, Valjean, seeing in Fantine similarities to his former life of hardship, promises her that he will take care of Cosette. He pays off the innkeeper, Thénardier, to obtain Cosette. Valjean and Cosette flee for Paris.

Ten years later, angry students, led by Enjolras, are preparing a revolution on the eve of the Paris uprising on June 5 and 6, 1832, following the death of General Lamarque, the only French leader who had sympathy towards the working class. One of the students, Marius Pontmercy, falls in love with Cosette, who has grown to be very beautiful. The Thénardiers, who have also moved to Paris, lead a gang of thieves to raid Valjean’s house while Marius is visiting. However, Thénardier’s daughter, Éponine, who is also in love with Marius, convinces the thieves to leave.

The following day, the students initiate their revolt and erect barricades in the narrow streets of Paris. Valjean, learning that Cosette's love is fighting, goes to join them. Éponine also joins. During the battle, Valjean saves Javert from being killed by the students and lets him go. Javert, a man who believes in absolute obedience of the law, is caught between his belief in the law and the mercy Valjean has shown him. Unable to cope with this dilemma, Javert kills himself. Valjean saves the injured Marius, but everyone else, including Enjolras and Éponine, is killed. Escaping through the sewers, he returns Marius to Cosette. Marius and Cosette are soon married. Finally, Valjean reveals to them his past, and then dies.

Themes

Grace

Among its many other themes, a discussion and comparison of grace and legalism is central to Les Misérables. This is seen most starkly in the juxtaposition of the protagonist, Valjean, and the apparent antagonist, Javert.

After serving 19 years, all Jean Valjean knows about is the judgment of the law. He committed a crime for which he suffered the punishment, although he feels that this is somehow unjust. Rejected because of his status as an ex-convict, Valjean first encounters grace when the bishop not only lies to protect him for stealing the two silver candlesticks from his table, but famously also makes a gift of the candlesticks to Valjean. This treatment that does not correspond to what Valjean "deserves" represents a powerful intrusion of grace into his life.

Throughout the course of the novel, Valjean is haunted by his past, most notably in the person of the relentless Javert. It is fitting then that the fruition of that grace comes in the final encounter between Valjean and Javert. After Javert is captured going undercover with the revolutionaries, Jean Valjean volunteers to execute him. However, instead of taking vengeance as Javert expects, he sets the policeman free. The bishop's act of grace is multiplied in the life of Jean Valjean, even extending to his arch-nemesis. Javert is unable to reconcile his black-and-white view with the apparent high morals of this ex-criminal and with the grace extended to him, and commits suicide.

Grace plays a positive moral force in Jean's life. Whereas prison has hardened him to the point of stealing from a poor and charitable bishop, grace sets him free to be charitable to others.

Political life and exile

After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the Académie Francaise in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. Thereafter he became increasingly involved in French politics as a supporter of the Republican form of government. He was elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe in 1841, entering the Higher Chamber as a Pair de France, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favor of freedom of the press and of self-government for Poland. He was later elected to the Legislative Assembly and the Constitutional Assembly, following the 1848 Revolution and the formation of the Second Republic.

When Louis Napoleon (Napoleon III) seized complete power in 1851, establishing an anti-parliamentary constitution, Hugo openly declared him a traitor of France. Fearing for his life, he fled to Brussels, then Jersey, and finally settled with his family on the channel island of Guernsey, where he would live in exile until 1870.

While in exile, Hugo published his famous political pamphlets against Napoleon III, Napoléon le Petit and Histoire d'un crime. The pamphlets were banned in France, but nonetheless had a strong impact there. He also composed some of his best work during his period in Guernsey, including Les Miserables, and three widely praised collections of poetry Les Châtiments (1853), Les Contemplations (1856), and La Légende des siècles (1859).

Although Napoleon III granted an amnesty to all political exiles in 1859, Hugo declined, as it meant he would have to curtail his criticisms of the government. It was only after the unpopular Napoleon III fell from power and the Third Republic was established that Hugo finally returned to his homeland in 1870, where he was promptly elected to the National Assembly and the Senate.

Religious views

Although raised by his mother as a strict Roman Catholic, Hugo later become extremely anti-clerical and fiercely rejected any connection to the church. On the deaths of his sons Charles and François-Victor, he insisted that they be buried without cross or priest, and in his will made the same stipulation about his own death and funeral.

Due in large part to the church's indifference to the plight of the working class under the monarchy, which crushed their opposition, Hugo evolved from non-practicing Catholic to a Rationalist Deist. When a census-taker asked him in 1872 if he was a Catholic, Hugo replied, "No. A Freethinker." He became very interested in spiritualism while in exile, participating in séances.

Hugo's rationalism can be found in poems such as Torquemada (1869), about religious fanaticism, The Pope (1878), violently anti-clerical, Religions and Religion (1880), denying the usefulness of churches and, published posthumously, The End of Satan and God (1886) and (1891) respectively, in which he represents Christianity as a griffin and rationalism as an angel. He predicted that Christianity would eventually disappear, but people would still believe in "God, Soul, and Responsibility."

Declining years and death

When Hugo returned to Paris in 1870, the country hailed him as a national hero. He went on to weather, within a brief period, the Siege of Paris, a mild stroke, his daughter Adèle’s commitment to an insane asylum, and the death of his two sons. His other daughter, Léopoldine, had drowned in a boating accident in 1833, while his wife Adele passed away in 1868.

Two years before his own death, Juliette Drouet, his lifelong mistress died in 1883. Victor Hugo's death on May 22, 1885, at the age of 83, generated intense national mourning. He was not only revered as a towering figure in French literature, but also internationally acknowledged as a statesman who helped to preserve and shape the Third Republic and democracy in France. More than two million people joined his funeral procession in Paris from the Arc de Triomphe to the Panthéon, where he was buried.

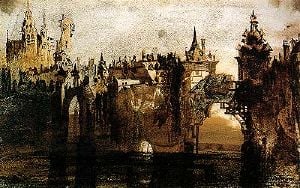

Drawings

Hugo was almost as prolific an artist as he was a writer, producing about 4,000 drawings in his lifetime. Originally pursued as a casual hobby, drawing became more important to Hugo shortly before his exile, when he made the decision to stop writing in order to devote himself to politics. Drawing became his exclusive creative outlet during the period 1848-1851.

Hugo worked only on paper, and on a small scale; usually in dark brown or black pen-and-ink wash, sometimes with touches of white, and rarely with color. The surviving drawings are surprisingly accomplished and modern in their style and execution, foreshadowing the experimental techniques of surrealism and abstract expressionism.

He would not hesitate to use his children's stencils, ink blots, puddles and stains, lace impressions, "pliage" or foldings (Rorschach blots), "grattage" or rubbing, often using the charcoal from match sticks or his fingers instead of pen or brush. Sometimes he would even toss in coffee or soot to get the effects he wanted. It is reported that Hugo often drew with his left hand or without looking at the page, or during spiritualist séances, in order to access his unconscious mind, a concept only later popularized by Sigmund Freud.

Hugo kept his artwork out of the public eye, fearing it would overshadow his literary work. However, he enjoyed sharing his drawings with his family and friends, often in the form of ornately handmade calling cards, many of which were given as gifts to visitors while he was in political exile. Some of his work was shown to and appreciated by contemporary artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Eugene Delacroix. The latter expressed the opinion that if Hugo had decided to become a painter instead of a writer, he would have outshone the other artists of their century.

Reproductions of Hugo’s striking and often brooding drawings can be viewed on the Internet at ArtNet and on the website of artist Misha Bittleston.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Online references

- Afran, Charles (1997). “Victor Hugo: French Dramatist". Website: Discover France. (Originally published in Grolier Multimedia Encyclopedia, 1997, v.9.0.1.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Bates, Alan (1906). “Victor Hugo". Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 11-13.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Bates, Alfred (1906). “Hernani". Website: Threatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 20-23.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Bates, Alfred (1906). “Hugo’s Cromwell". Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, vol. 9. ed. Alfred Bates. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. pp. 18-19.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Bittleston, Misha (uncited date). "Drawings of Victor Hugo". Website: Misha Bittleston. Retrieved November 2005.

- Burnham, I.G. (1896). “Amy Robsart". Website: Theatre History. (Originally published in Victor Hugo: Dramas. Philadelphia: The Rittenhouse Press, 1896. pp. 203-6, 401-2.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Edition (2001-05). “Hugo, Victor Marie, Vicomte". Website: Bartleby, Great Books Online. Retrieved November 2005. Retrieved November 2005.

- Fram-Cohen, Michelle (2002). “Romanticism is Dead! Long Live Romanticism!". The New Individualist, An Objectivist Review of Politics and Culture. Website: The Objectivist Center. Retrieved November 2005.

- Haine, W. Scott (1997). “Victor Hugo". Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions. Website: Ohio University. Retrieved November 2005.

- Illi, Peter (2001-2004). “Victor Hugo: Plays". Website: The Victor Hugo Website. Retrieved November 2005.

- Karlins, N.F. (1998). "Octopus With the Initials V.H." Website: ArtNet. Retrieved November 2005.

- Liukkonen, Petri (2000). “Victor Hugo (1802-1885)". Books and Writers. Website: Pegasos: A Literature Related Resource Site. Retrieved November 2005.

- Meyer, Ronald Bruce (date not cited). “Victor Hugo". Website: Ronald Bruce Meyer. Retrieved November 2005.

- Robb, Graham (1997). “A Sabre in the Night". Website: New York Times (Books). (Exerpt from Graham, Robb (1997). Victor Hugo: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Roche, Isabel (2005). “Victor Hugo: Biography". Meet the Writers. Website: Barnes & Noble. (From the Barnes & Noble Classics edition of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 2005.) Retrieved November 2005.

- Uncited Author. “Victor Hugo". Website: Spartacus Educational. Retrieved November 2005.

- Uncited Author. “Timeline of Victor Hugo". Website: BBC. Retrieved November 2005.

- Uncited Author. (2000-2005). “Victor Hugo". Website: The Literature Network. Retrieved November 2005.

Further reading

- Barbou, Alfred (1882). Victor Hugo and His Times. University Press of the Pacific. 2001 paperback edition. ISBN 089875478X

- Brombert, Victor H. (1984). Victor Hugo and the Visionary Novel. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674935500

- Davidson, A.F. (1912). Victor Hugo: His Life and Work. University Press of the Pacific. 2003 paperback edition. ISBN 1410207781

- Dow, Leslie Smith (1993). Adele Hugo: La Miserable. Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions. ISBN 0864921683

- Falkayn, David (2001). Guide to the Life, Times, and Works of Victor Hugo. University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 0898754658

- Frey, John Andrew (1999). A Victor Hugo Encyclopedia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313298963

- Grant, Elliot (1946). The Career of Victor Hugo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Out of print.

- Halsall, A.W. et al (1998). Victor Hugo and the Romantic Drama. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802043224

- Hart, Simon Allen (2004). Lady in the Shadows : The Life and Times of Julie Drouet, Mistress, Companion and Muse to Victor Hugo. Publish American. ISBN 1413711332

- Houston, John Porter (1975). Victor Hugo. New York: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0805724435

- Ireson, J.C. (1997). Victor Hugo: A Companion to His Poetry. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198157991

- Maurois, Andre (1966). Victor Hugo and His World. London: Thames and Hudson. Out of print.

- Robb, Graham (1997). Victor Hugo: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1999 paperback edition. ISBN 0393318990. (Description/reviews)

Works

Published during Hugo's lifetime

- Nouvelles Odes (1824)

- Bug-Jargal (1826)

- Odes et Ballades (1826)

- Cromwell (1827)

- Les Orientales (1829)

- Le Dernier jour d'un condamné (1829)

- Hernani (1830)

- Notre-Dame de Paris (1831), (translated into English as The Hunchback of Notre Dame)

- Marion Delorme (1831)

- Les Feuilles d'automne (Autumn Leaves) (1831)

- Le roi s'amuse (1832)

- Lucrèce Borgia Lucrezia Borgia (1833)

- Marie Tudor (1833)

- Étude sur Honoré Mirabeau (1834)

- Littérature et philosophie mêlées (1834)

- Claude Gueux (1834)

- Angelo (1835)

- Les Chants du crépuscule (1835)

- Les Voix intérieures (1837)

- Ruy Blas (1838)

- Les Rayons et les ombres (1840)

- Le Rhin (1842)

- Les Burgraves (1843)

- Napoléon le Petit (1852)

- Les Châtiments (1853)

- Lettres à Louis Bonaparte (1855)

- Les Contemplations (1856)

- La Légende des siècles (1859)

- Les Misérables (1862),

- William Shakespeare (essay) (1864)

- Les Chansons des rues et des bois (1865)

- Les Travailleurs de la Mer (1866), (Toilers of the Sea)

- Paris-Guide (1867)

- L'Homme qui rit (1869), (The Man Who Laughs)

- L'Année terrible (1872)

- Quatre-vingt-treize Ninety-Three (1874)

- Mes Fils (1874)

- Actes et paroles — Avant l'exil (1875)

- Actes et paroles - Pendant l'exil (1875)

- Actes et paroles - Depuis l'exil (1876)

- La Légende des Siècles 2e série (1877)

- L'Art d'être grand-père (1877)

- Histoire d'un crime 1re partie (1877)

- Histoire d'un crime 2e partie (1878)

- Le Pape (1878)

- Religions et religion (1880)

- L'Âne (1880)

- Les Quatres vents de l'esprit (1881)

- Torquemada (1882)

- La Légende des siècles Tome III (1883)

- L'Archipel de la Manche (1883)

Published posthumously

- Théâtre en liberté (1886)

- La fin de Satan (1886)

- Choses vues - 1re série (1887)

- Toute la lyre (1888)

- Alpes et Pyrénées (1890)

- Dieu (1891)

- France et Belgique (1892)

- Toute la lyre - nouvelle série (1893)

- Correspondances - Tome I (1896)

- Correspondances - Tome II (1898)

- Les années funestes (1898)

- Choses vues - 2e série (1900)

- Post-scriptum de ma vie (1901)

- Dernière Gerbe (1902)

- Mille francs de récompense (1934)

- Océan. Tas de pierres (1942)

- Pierres (1951)

Online texts

All links retrieved March 26, 2014.

- Les Misérables online

- The Hunchback of Notre Dame online

- E-texts of some of Hugo's works from various sources

- The France of Victor Hugo

- Guernsey’s Official Victor Hugo Website

- Victor Hugo Central

- Victor Hugo Website

- Political speeches by Victor Hugo: Victor Hugo, My Revenge is Fraternity!

- Biography

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 20:36:20 | 5 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Victor_Hugo | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF