Oregon Trail

From Conservapedia

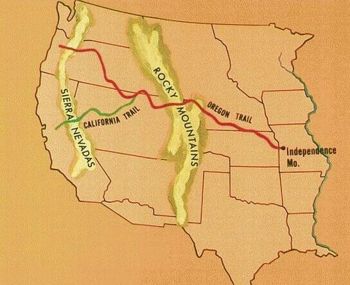

From Conservapedia The Oregon Trail was the 2000 mile overland route by which people walked for six months from the Midwest to Oregon and the northern West Coast before the railroad opened in 1869. It was one of the great routes used to open the American frontier—people wanted the cheap rich farmlands, as well as the adventure and the self-determination involved in creating new communities. The route was the most efficient way to travel, but involved crossing wide rivers and high mountains; there were many attacks by Indians, so settlers normally went in groups of 100 to 500 people in wagon trains.

Contents

Origins[edit]

The most efficient route from the Missouri River to the Columbia River was discovered by explorers and fur traders. In 1805 the Lewis and Clark Expedition mapped one difficult part through the mountains of Idaho. In (1808) fur trappers from the Missouri Fur Company discovered the South Pass in Wyoming. In 1812 fur traders from Astoria, Oregon, led by Robert Stuart came east largely following the route. The first great organized trip came in 1832 under Nathaniel Wyeth. His party made it overland in good shape, but the ship Wyeth sent ahead via the southern tip of South America was lost at sea, along with all the trade goods he planned to sell. So he sailed back to Boston, sent another ship ahead and made a second overland trek in 1834. Wyeth’s journal made the trail very well known. Methodist missionaries soon followed, most notably Marcus Whitman, making Oregon an outpost in an otherwise dechristianized region.

By 1842 the trail had become a deeply rutted dirt road used by the pioneers in their covered wagons. Knowledge of the trail became common property. Wagon trains obtained this knowledge from guides who knew it well; there were also printed guidebooks, but those were mostly useful for reassuring people it was reasonable to make the arduous six-months journey. One early guidebook[1] shows the distances involved. His waypoints included conspicuous landmarks, difficult streams to ford, and supply posts where food and supplies could be purchased. From the Missouri River to the mouth of the Columbia River as follows:

- From Independence to the Crossings of Kansas 102 miles

- Crossings of Blue 83

- Platte River 119

- Crossings of South Platte 163

- To North Fork 20

- To Fort Laramie 153

- From Fort Laramie to Crossing of North Fork of the Platte 140

- To Independence Rock on Sweet Water 50

- To Fort Bridger 229

- To Bear River 68

- To Soda Springs 94

- To Fort Hall 57

- To Salmon Falls 160

- To Crossings of Snake River 22

- To Crossings of Boise River 69

- To Fort Boise 45

- To Dr. Whitman's Mission 190

- To Fort Walawala [Walla Walla] 25

- To Dallis Mission [The Dalles] 120

- To Cascade Falls, on the Columbia 50

- To Fort Vancouver 41

The rich farmlands of Oregon’s Willamette Valley drew most of the travelers, but others remained in good lands along the way, or split off to go to California.

Emigrating societies[edit]

Excitement about Oregon grew in the 1840s after the boundary dispute with Britain had been settled. People back east formed emigrating societies to plan, finance and recruit. By lectures, letters, and personal visits, members of these societies secured recruits.

On the trail[edit]

The town of Independence, Missouri, was the usual jumping off point. As they moved out the wagon party organized a self-government by electing officers and adopting rules of conduct. The emigrants gathered in time to leave in the early spring, so as to take advantage of the fresh pasturage for their oxen, horses and cattle. From Independence they followed the old Santa Fe Trail across flat grasslands (now in Nebraska). At Fort Laramie (now in Wyoming), the base of the mountains, they trains stopped for repairs and resupply The trail used South Pass to cross the Rocky Mountains at a relatively low elevation of “only” 7,500 feet. Travel now became much harder. Much of the land was barren with poor pasturage, or involved steep climbs and descents, wearing out the already exhausted horses and oxen. There was no alternative but to throw away excess baggage and furniture. Carcasses of the innumerable dead cattle and horses were left along the trail while the bodies of the human dead were buried in shallow graves with simple markers. The Grande Ronde Valley, in northeast Oregon, had good pasturage, a breather before they had to cross the difficult Blue Mountains. Coming down on the other side the trains followed the Umatilla River to the Columbia River, which they followed to Fort Vancouver. Traveling through the Columbia River Gorge from The Dalles to Portland was a new challenge. Traversing the gorge usually meant putting their wagons and possessions on makeshift rafts and boats and heading downstream, a passage that varied from placid waters necessitating poling to dangerous rapids. A trail paralleling the river was used to bring cattle and other livestock. Travelers endured bad weather, wind, sanitation problems, disease, and the fatigue that came at the end of a trek across the continent. Forage was scarce and food supplies dwindled.

Life and death[edit]

The wagon traffic during the 1840s and 1850s was so heavy that the road was a clearly defined and deeply rutted way across the country. When the ruts became too deep for travel, parallel roads were broken. The 2,000 mile trek tested the outer limits of human endurance and organizational skill. The many surviving diaries of the overland journey invariable mention the graves passed each day. Cholera was the most serious medical problem. After 1850 the wagon trains used better-adapted equipment. Specially constructed wagons became available; oxen largely replaced horses; and supplies were selected more wisely. The route was now easy to follow and even included crude ferries at some of the most difficult river crossings.

Food problems were eased by the use of "portable soup" tablets(bouillon cubes), meat biscuits and powdered milk (the latter two invented by Gail Borden). Mostly they ate salted pork, biscuits, soup and dried fruit, supplemented with wild game shot along the way. Canned foods were available after 1850.[2]

Memory[edit]

Scotts Bluff National Monument was created by Congress in 1919 in western Nebraska. It represents the public memory of westward migration along the Oregon Trail and a meaningful place in the collective memory of local residents. These meanings, although not necessarily contradictory, diverged in ways that made management of the monument a source of controversy between local and national parties. Federal officials sought to emphasize the historic importance of Scotts Bluff and its national symbolic value, while locals wanted to continue using the monument as they always had - for picnics, hikes, golf, and even an annual soap box derby. Yet the process of establishing and interpreting the monument fostered the development of a local community identity inextricably linked to the monument.[3]

A centenary commemoration of the Oregon Trail was held at Independence Rock, Wyoming, in July 1930. The event was promoted by Howard Driggs, an energetic author who became leader of the Oregon Trail Memorial Association, founded in the early 1920s by Oregon Trail pioneer Ezra Meeker. In 1941 the American Pioneer Trails Association, a group of trail enthusiasts that grew out of the Oregon Trail Memorial Association, organized an auto caravan between Marysville, Kansas, and Denver, Colorado. The Great Platte River Road Archway Monument east of Kearney, Nebraska, opened in 2000. Eight stories tall and straddling Interstate 80, the museum tells the story of the settling of the frontier West. The Oregon Trail, Gold Rush, Pony Express, and Lincoln Highway, for example, are brought to life through video reenactments, displays, and assorted primary materials. The National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center operates near Baker City, Oregon. It offers living history demonstrations, interpretive programs, exhibits, multi-media presentations, special events, and four miles of interpretive trails.

Bibliography[edit]

- Dary, David. The Oregon Trail: An American Saga (2005), 420pp; outstanding scholarly history; covers entire history, and 20th century memory; makes heavy use of first-hand accounts

- Lavender, David. Westward Vision: The Story of the Oregon Trail. (1961) online edition, good popular history

- Unruh, John D., Jr. The Plains Across: The Overland Emigrants and the Trans-Mississippi West, 1840-1860. (1979), an outstanding scholarly history. excerpt and text search

- Williams, Jacqueline. Wagon Wheel Kitchens: Food on the Oregon Trail. (1993). 222 pp.

Primary sources[edit]

- Moeller, Bill and Moeller, Jan. The Oregon Trail: A Photographic Journey. (Missoula: Mountain Press, 2001). 301 pp.

- Morgan, Dale. Overland in 1846: Diaries and Letters of the California-Oregon Trail (2 vol 1993) vol 1 online; vol 2 online

- Parkman, Francis. The Oregon Trail (1849); one of the great classics of American writing; online edition

External links[edit]

note[edit]

Categories: [United States History]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/14/2023 11:06:50 | 49 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Oregon_Trail | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF