Aleutian Islands

From Nwe

From Nwe The Aleutian Islands (possibly from the Chukchi language aliat, meaning "island") are a chain of more than 150 mostly volcanic islands forming an island arc that seperates the Bering Sea in the north from the main portion of the Pacific Ocean. These islands occupy an area of 6,821 square miles (17,666 km²) and extend about 1,100 mi (1,800 km) westward from the tip of the Alaska Peninsula toward Attu Island in Alaska. Crossing longitude 180°, they are the westernmost part of the United States. Nearly all the archipelago is part of Alaska and usually considered as being in the "Alaskan Bush," including the small, geologically-related, and remote Komandor Islands which are a part of Russia, at the extreme western end. The islands form a natural bridge between the continents and are believed to have been the stepping stones of the first inhabitants to enter North America.

The islands, including their 57 volcanoes, are in the northern part of the Circum-Pacific chain of volcanoes, commonly referred to as the Pacific Ring of Fire. The Alaska Marine Highway passes through the islands, which includs the Unimak, Umnak, Amukta, and Seguam passes. [1]

The Aleutians are home to abundant wildlife, including 40,000,000 seabirds, rare Asiatic migrant birds, sea lions and fur seals. The Aleutian Islands received international recognition in 1976 as a biosphere reserve, designated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). [2]

Geography

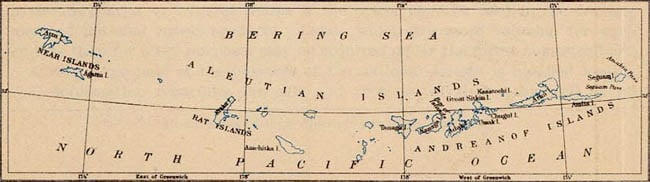

The Aleutian Islands, known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, comprise five groups: the Fox which is nearest to the mainland, Islands of Four Mountains, Andreanof, Rat and Near islands, the smallest and most western group. They are all located between 51° and 55° N latitude and 173° E and 161° W longitude.

The axis of the archipelago near the mainland of Alaska has a southwest trend, but near the 129th meridian its direction changes to the northwest. This change of direction corresponds to a curve in the line of volcanic fissures that have contributed their products to the building of the islands. Such curved chains are repeated about the Pacific Ocean in the Kuril Islands, the Japanese chain and in the Philippines. All these island arcs lie between the North American plates and the Pacific Plate and experience a lot of seismic activity, but are still habitable. The general elevation is greatest in the eastern islands, reaching up to 6,230 feet, and least in the western islands. The island chain is a western continuation of the Aleutian Range on the mainland.

The great majority of the islands bear evident marks of volcanic origin. There are many volcanic cones on the north side of the chain, some of them active, however; many of the islands are not wholly volcanic, but contain crystalline or sedimentary rocks, and also amber and beds of lignite. The coasts are rocky and surf-worn, and the approaches are exceedingly dangerous, the land rising immediately from the coasts to steep, bold mountains.

Makushin Volcano (5906 ft/1,800 m) located on Unalaska Island, is not quite visible from within the town of Unalaska, though the steam rising from its cone is visible on a (rare) clear day. Denizens of Unalaska need only to climb one of the smaller hills in the area, such as Pyramid Peak or Mt. Newhall, to get a good look at the snow-covered cone. The volcanic Bogoslof and Fire Islands, which rose from the sea in 1796 and 1883 respectively, lie about 30 miles (48 km) west of Unalaska Bay.

In 1906 a new volcanic cone rose between the islets of Bogoslof and Grewingk, near Unalaska, followed by another in 1907. At that time, Fire Island had stopped smoking, as apparently had Bogoslof. These cones were nearly demolished by an explosive eruption on September 1, 1907.

Climate

The climate of the islands is oceanic, with moderate and fairly uniform temperatures and heavy rainfall. The climate is characterized by frequent cyclonic storms and high winds, and during calm periods the region is often covered by a dense fog. Summer weather in the archipelago is much cooler than Southeast Alaska (Sitka), but the winter temperature of the islands and of the Alaska Panhandle is very nearly the same. In this zone the summer temperatures are moderated by the open waters of the Bering Sea, but winter temperatures are more continental in nature due to the presence of sea ice during the coldest months of the year. [3] The mean annual temperature for Unalaska, the most populated island of the group, is about 38 °F (3.4 °C), being about 30 °F (−1.1 °C) in January and about 52 °F (11.1 °C) in August. The highest and lowest temperatures recorded on the islands are 78 °F (26 °C) and 5 °F (−15 °C) respectively. The annual precipitation ranges from 32 to 65 inches (810 to 1,650 mm), and Unalaska, with about 250 rainy days per year, is said to be one of the rainiest places within the United States. Sitka used to be considered the rainiest part of the United States, however only has 207.9 rainy days per year. This type of climate is only comparable to those of: Iceland, Tierra del Fuego and neighboring Alaska Peninsula.

Flora and fauna

The growing season lasts from the beginning of June to the middle of September, but agriculture is limited to the raising of a few vegetables.

With the exception of some stunted willows, the vast majority of the chain is destitute of native trees. On some of the islands, such as Adak and Amaknak, there are a few coniferous trees growing, remnants of the Russian period. But these trees, some of them estimated to be two hundred years old, rarely reach a height of even ten feet, and many of them are still less than five feet tall. These trees had originally been brought from Sitka, where summers reach 14 ºC. The summers in Aleutian Islands do not get warm enough to favor a good growth for these transplants.

In comparison, the native forests in Tierra del Fuego, which has a similar climate, tolerate very cold temperatures in summer (9º C).

Devoid of trees, the islands are covered with a luxuriant, dense growth of herbage, including grasses, sedges and many flowering plants.

The Aleutians are home to sea otters, seals, puffins, fulmars, murres, and millions of seabirds which use the islands as nesting habitat.

Preservation efforts

The Aleutian Islands unit of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge (part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) covers over 4,200 square miles and extends between Attu Island on the west and Unimak Island on the east. The Refuge protects the vast wildlife of the Islands, and their habitats, thus protecting the way of life of the Aleuts, who have always lived by hunting and fishing. [4]

History

Prehistory

Because of the location of the islands, stretching like a broken bridge from Asia to North America, many anthropologists believe they were a route for the first human occupants of the Americas. The earliest known evidence of human occupation in the Americas is much further south, in New Mexico and Peru; the earliest human sites in Alaska have probably been submerged by rising waters during the current interglacial period.

It is believed that the Aleutian Islands were first inhabited by people that moved to Alaska across the Bering Land Bridge perhaps 15,000 years ago. The Aleuts survived on the islands' bounty and the surrounding marine environment, developing fine skills in hunting, fishing, and basketry. Hunters made their weapons and watercraft. The baskets are noted for being finely woven with carefully shredded stalks of beach rye.

Russian period

Explorers, traders, colonists, fur traders, and missionaries arrived from Russia beginning in 1741. At this time, the Russian government sent Vitus Bering, a Dane in the service of Russia, and Alexei Chirikov, a Russian, in the ships Saint Peter and Saint Paul on a voyage of discovery in the Northern Pacific.

The pair of ships were separated during a storm, allowing Chirikov to discover several eastern islands of the Aleutian group, while Bering discovered several of the western islands (including Mount Saint Elias).

Bering's ship wrecked and he lost his life on the Komandorski Islands (Commander Islands) that now bear his name, (Bering Island). The survivors of Bering's party reached the Kamchatka Peninsula in a boat constructed from the wreckage of their ship, and reported that the islands were rich in fur-bearing animals.

Siberian fur hunters flocked to the Commander Islands and gradually moved eastward across the Aleutian Islands to the mainland. In this manner Russia gained a foothold on the northwestern coast of North America. The Aleutian Islands consequently belonged to Russia, until that country transferred all its possessions in North America to the United States in 1867.

The Russians were ruthless in their expansion, using technology and cruelty to enslave the Aleuts, especially for sea otter hunting. The Russians captured otter pelts from the Aleutian Islands, through the Gulf of Alaska, along the Alaska Panhandle, and south, even to California. Many Aleuts were moved to the Pribilof Islands on a seasonal basis, many times against their will, so that fur seals could be captured there as well.

In the 1760s, the Russian merchant Andrean Tolstykh made a detailed census in the vicinity of Adak Island and extended Russian citizenship to the Aleuts.

Despite some attempts to eliminate slavery and reduce cruel treatment in the 1790s, the Russian-American Shelikhov company depended on the labor of Aleut hunters to collect sea otter pelts. Soon after the Russians had arrived on their island, Aleut women had also begun working for the company. While men were out on the hunt, women prepared food for the company by drying fish on long poles and collecting berries, as well as making birdskin parkas that the company gave to the Aleutian people to wear in exchange for their work. [5]

During his third and last voyage, in 1778, Captain James Cook surveyed the eastern portion of the Aleutian archipelago, accurately determined the position of some of the more important islands and corrected many errors of former navigators.

Christian influences

One of the first Christian missionaries to arrive in the Aleutian Islands was a monk named Herman, who arrived on September 24, 1794 with nine other Russian Orthodox monks and priests (6 monks and 4 novices) on what was referred to as the Valaam Mission to Alaska.

Within two years, Herman was the only survivor of the party. He settled on Spruce Island (which he called "New Valaam"), near Kodiak Island, and often defended the rights of the Aleuts against the Russian trading companies. He spent the rest of his life on this island, where he cared for orphans, ran a school and continued his missionary work. He is now known in the Orthodox Church as St. Herman of Alaska.

In 1823 Ivan Veniaminof, of the Russian Orthodox Church, known as the "Enlightener of the Aleuts," arrived in Unalaska. During his career of nearly thirty years, he displayed intense zeal. He was instrumental in spreading Christianity over a vast extent of territory, visiting not only the Aleutian Islands, but all the coast of the mainland from Bristol Bay to the Kuskokwim.

Veniaminof was a man of exceptional ability. Mastering the Aleut and Tlingit languages, he translated portions of the New Testament, composed a catechism and hymnal, and began an exhaustive research into the traditions, beliefs and superstitions of the tribes within the Aleutian group. In 1840, after the division of the diocese of Irkutsk, he was consecrated Bishop of Kamchatka, the Kuril and Aleutian Islands, and assumed, after the Russian custom, the name of Innocentius, at which point in time, he moved to Sitka. [6] He is now known in the Orthodox Church as Saint Innocent of Alaska.

The principal settlements were on Unalaska Island. The oldest was Iliuliuk (also called Unalaska), settled in 1760-1775, with a customs house, a Methodist Mission and orphanage, and an Orthodox church.

Alaska's transfer to United States

Russia was in a difficult financial position and feared losing the Alaskan territory without compensation in a future conflict, especially to their rivals the British, who could easily capture the hard-to-defend region. Therefore Czar Alexander II decided to sell the territory to the United States, instructing the Russian minister to the U.S., Eduard de Stoeckl, to enter into negotiations with William Seward, the U.S. Secretary of State, in the beginning of March 1867.

The negotiations concluded after an all-night session with the signing of the treaty at 4 o'clock in the morning of March 30, with the purchase price set at $7,200,000 (approximately 1.9¢ per acre).

The purchase was derided by many in the U.S. as Seward's folly, Seward's icebox, and Andrew Johnson's polar bear garden, because it was believed foolhardy to spend so much money on the remote region.

Secretary of State William H. Seward, who had long favored expansion, and the chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Charles Sumner supported the purchase. They argued that the nation's strategic interests favored the treaty. Russia had been a valuable ally during the Civil War, while Britain had been an open enemy. It seemed wise to help Russia while discomforting the British.

On April 9th Sumner made a major speech advocating the treaty, and covering in depth the history, the climate, the natural configuration, the population, the resources—the forests, mines, furs, fisheries—of Alaska. A good scholar, he cited the testimony of geographers and navigators: Alexander von Humboldt, Joseph Billings, Yuri Lisiansky, Fyodor Petrovich Litke, Otto von Kotzebue, Portlock, James Cook, Meares, Ferdinand von Wrangel.

Soon, said Sumner, "A practical race of intrepid navigators will swarm the coast ready for any enterprise of business or patriotism. Commerce will find new arms; the country new defenders; the national flag new hands to bear it aloft." Bestow American republicanism upon the territory, he urged, "and you will bestow what is better than all you can receive, whether quintals of fish, sands of gold, choicest fur or most beautiful ivory."

After the American purchase further development of the Aleutians took place. New buildings included a Presbyterian mission (the Wrangall Mission) and a boarding school for girls, and the headquarters for a considerable fleet of U.S. revenue cutters which patrolled the sealing grounds of the Pribilof Islands. The first public school in Unalaska opened in 1885, with an enrollment of 45 students.

The U.S. Congress extended American citizenship to all Natives (which includes the indigenous peoples of Alaska) in 1924.

A hospital was built in Unalaska in 1932 by the US Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Bureau also opened the Wrangell Institute, a co-educational vocational boarding school in 1932. In 1947, the Wrangell Institute became an elementary school, and eventually closed in 1975.

Western Aleutian Islands, from a 1916 map of the Alaska Territory

World War II

In 1940, the United States established a naval base in Dutch Harbor, one of the few good harbors on the chain. This area was of great strategic interest, made clear on June 3, 1942 when the base was attacked by Japan. This attack came to be called the "Pearl Harbor of the North." During World War II, small areas of the Aleutian islands were occupied by Japanese forces, when Attu and Kiska were invaded in order to divert American forces away from the main Japanese attack at Midway Atoll. The U.S. Navy, having broken the Japanese naval radio codes, knew that this was a diversion, and it did not expend large amounts of effort in defending the islands.

Forty two Americans were taken to a prison camp in Hokkaido, Japan, where 16 of them died. Most of the civilian population of the Aleutians were interned by the United States in camps in the Alaska Panhandle. American forces invaded Japanese-held Attu and defeated the Japanese, subsequently regaining control of all the islands. The islands were also a stopping point for hundreds of aircraft sent from California to Russia as part of the war effort.

Monday, June 3, 2002 was celebrated as Dutch Harbor Remembrance Day. The governor of Alaska ordered state flags lowered to half-staff to honor the 78 soldiers who died during the two-day Japanese air attack in 1942. The Aleutians World War II Campaign National Historic Area Visitors Center opened in June 2002.

Recent developments

After World War II a U.S. Coast Guard fleet was stationed at Unalaska Island to patrol the sealing grounds and, after 1956, to enforce a convention on seal protection agreed upon by the United States, Canada, Japan, and the Soviet Union.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) became law in 1971, which allowed the local land and financial resources to be under the control of Native corporations. In 1977, the Ounalashka Corporation (a real estate leasing and development company formed to manage the lands transferred to Alaska located in Unalaska) declared a dividend. This was the first village corporation to declare and pay a dividend to its shareholders.

Economy

On the less-mountainous islands, the raising of sheep and reindeer was once believed to be practicable. During the 1980s, there were some llama being raised on Unalaska. The raising of blue foxes has furnished employment for many as well. Today, the economy is primarily based upon fishing, and, to a lesser extent, the presence of American military.

Demographics

The native people refer to themselves as Unangan, and are more commonly known by most non-natives as the "Aleut."

The Aleuts speak three mutually-intelligible dialects, and are closely related to the Eskimo-Aleut language family. This family is not known to be related to any others. The Aleut or Unangan (Eastern and Attuan) and Unangas (Atkan or Western) language was spoken by the Unangan people before the Russian fur traders and Scandinavian fishermen came to the Aleutians.

At one time, an Aleut commonly spoke Aleut, Russian and English. But, today English is the language the Aleut people most commonly use. [7]

In the 2000 census, there was a population of 8,162 on the islands, of whom 4,283 were living in the main settlement of Unalaska.

Notes

- ↑ The Aleutians, The Aleutians Homepage. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ↑ Wild Lands, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ↑ Climate of Alaska, Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ↑ Alaska Region, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ↑ History, Common Place History. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ↑ Missions, The Russion Mission. Retrieved April 17, 2007.

- ↑ Culture, The Aleut Corporation. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

Sources and further reading

- Aleutian Islands, Classic Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Southwest Alaska. Alaskan History and Culture Studies. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- The Aleuts of the Pribilof Islands, Alaska. The Amiq Organization. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Aleutian Islands. U.S. Army Center of Army History. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Geospatial information: how-to. DLESE Metadata. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Area Specific Management for the Aleutian Islands. National Marine Fisheries Service. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Aleutian Oceanic Meadow - Heath. Forest Service Department of Agriculture.. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Alaska Science Forum. Geophysical Institute. October 26, 1981. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Aleutian History. Aleutian's Home Page. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Aleutian Islands. Info Please.. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Primary Documents in American History. The Library of Congress. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Monthly Weather Review. National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. June 1906. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Archaeological Overview of Alaska. Prehistory of Alaska. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Physical Characteristics of the Region. Naval Research Laboratory. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- The Lives of the Saints of Alaska. Outreach Alaska.

- Alaska Native History and Cultures Timeline. Alaska's Digital Archives. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Introduction: The Pre-Presbyterian Years. Presbyterian Church U.S.A. Retrieved April 22, 2007.

- Aleutian Islands, Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Aleutian Islands.

- MacGarrigle, George L. Aleutian Islands. The U.S. Army campaigns of World War II, 72-6. Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History,1992. ISBN 0160358825 and ISBN 9780160358821

- Hays, Otis. Alaska's hidden wars: secret campaigns on the North Pacific rim. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2004. ISBN 1889963631 and ISBN 9781889963631

- Harrison, Sue. Brother Wind: a novel. New York: W. Morrow, 1994. ISBN 0688128882 and ISBN 9780688128883

External links

All links retrieved May 15, 2021.

- Treaty with Russia for the Purchase of Alaska. The Library of Congress.

- Treaty with Russia (Alaska Purchase). Bartleby.

- The Alaska Purchase. The Library of Congress. The Alaska Purchase.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 21:55:38 | 56 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Aleutian_Islands | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF